Everard Bullis was just 21 years old when his U.S. Marine Corps regiment entered what he called the “Big Fight” at Belleau Wood.

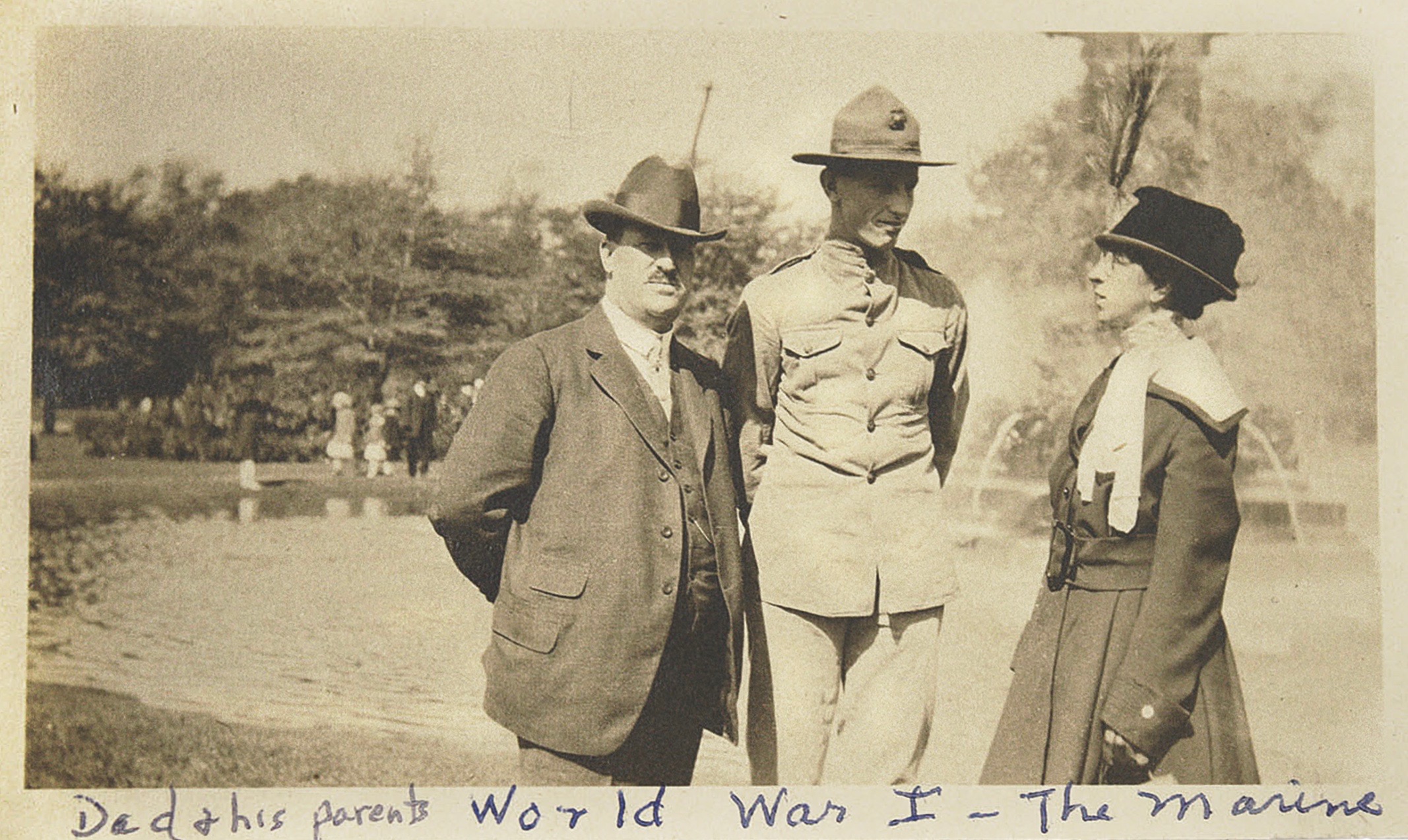

On June 9, 1917, nine weeks after the United States declared war on Germany, 20-year-old Everard J. Bullis—the only boy of five siblings in a middle-class family in St. Paul, Minnesota—enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, waiting until that evening to spring the news on his parents and sisters. Soon he was in its newly established boot camp at Quantico, Virginia, preparing for what he called, in one letter home, the “Big Fight.” On April 9, 1918, his battalion had a final inspection and review by Brigadier General John A. Lejeune, Quantico’s commandant. “The blood was racing through my body and chills ran up and down my spine,” Bullis would write in his diary the following day. “I felt like a warhorse for fight.”

In the second volume of the diaries he faithfully kept during World War I, Bullis described in detail the 5th Marine Regiment’s experiences on the Western Front, including its desperate stand against repeated German assaults at Belleau Wood and actions at Soissons, St. Mihiel, and Blanc Mont Ridge.

Bullis died in 1964 at age 67, but years later David J. Bullis discovered his grandfather’s diaries and published them in edited form as Doing My Bit Over There: A U.S. Marine’s Memoir of the Western Front in World War I (McFarland & Company, 2018), from which the following account is adapted.

The environs of Belleau Wood were scenic and pleasing to the eye. It was a rolling country, with most of the hills capped with trees. And the open fields and side hills were cropland, covered with grain.

There were numerous little villages in the valleys. They were not like the barren villages at home, with their solitary buildings dotting the surrounding countryside; but they were in clusters, built along the main road and also a side road or two. The masonry homes, barns, and other buildings appeared tied together by high masonry walls, and there were no front and back yards, as at home, but the buildings abutted the street. And each home had a courtyard, in which were kept chickens, the work animals, and an accumulation of junk.

There did not appear to be any stores where clothing, hardware, or groceries could be bought; only a shop, or two, liquors and wines the customary goods dispensed. There were no movie houses, no pool halls, or other places of amusement; there were no phones or other developments one would see in modern America. There was a church, not modern, usually with the highhipped roof and a spire, and a clock in the tower, built in the 1600s. And there were shrines at various places in the town, where the people knelt and prayed as they passed to and fro. This, then, was the setting of war.

Vicious, modern war had come and disrupted life in these villages. The homes and other buildings had been hit countless times by both light and heavy artillery; the masonry walls were tumbled down, and the roads were cratered by shell-bursts. The inhabitants of the villages were gone, except, perhaps, for a few old men and women, who chose to take their chance on life and with the enemy. For the most part, they were just ghostly habitations, and the inhabitants were the soldiers who occupied the remains.

The grain fields were lush with growth but were crisscrossed with paths, a line of trenches, and acres of barbed-wire entanglements. The farmers were gone, and during the day not a soul was seen—but night was alive with hurrying soldiers carrying out their various details. In the woods only, in the daylight hours, was there life, for the soldiers were to be seen moving about.

There were trenches cutting the border of the trees and wire entanglements strung about and through them. There were the isolated locations of batteries, the guns erupting in fire and smoke as they fired on unseen targets a kilometer or so away. And in the underbrush you would find the huddled bodies of the slain and their equipment, letters, and personal belongings strewn about. In the more cleared areas, the living, huddled in fire trenches, and others walking about.

But of bird life and small animals there was nothing, except a hare or two. And over all there hung a cloudy emanation, the acrid smoke of big guns and little, the smoke and debris of bursting shells, and perhaps the acrid or pungent odor of gas. And over the area, and for miles around, hung the air of death; the sweetish, sickening odor of the dead, the unburied, and the wounded. Such was Belleau Wood.

One evening, near dusk, several of us were placed on the line. It was an area clear of trees, and our detail was to do “panel” work for the air force. It was explained that at a certain time a plane marked with a trailer or streamer halfway out on the right wing would fire a three star rocket and then swoop low over the position to take pictures. At the signal, we were to display our panel, a strip of white cloth, perhaps 2 feet wide by 6 feet long, leaving it exposed while the plane flew over. This was necessary for the artillerymen to determine by the pictures the front line, or point of advance, and save us from “shorts” from the guns.

On this night, we were spread out and waiting, and then a plane appeared. The plane had the streamer positioned exactly; the plane did fire a rocket as prescribed; and we spread out the panels. As the plane swooped down to get the pictures, we perceived the German cross on its wings—and most of us hurried to gather in our panels. We were too late, in most cases, and as a result we were treated to an unusual bombardment from the enemy that night.

As for our plane, it never appeared, and we wondered at that.

The next few days held nothing too serious for us. One day, another marine and I were detailed to carry out a dead marine that lay in the tangled brush not far from our position. He was from our company, decomposition was far advanced, and the job was not nice. I reached the body first, and at first glance took the lead position of the stretcher. He had died on the stretcher, his wounds in the groin, and maggots were busily at work in the wounds and about the nostril and mouth.

We picked up the stretcher with the gruesome remains and started to the rear area. We had not gone far when the rear of the stretcher dropped, and I heard the retching of my companion: It was too gruesome for him. So we changed places and once more went on.

We had been told to cross no cleared areas and to keep to the woods, but bucks will take the easiest way out. We crossed a large cleared area on the run—they were right, for we were targeted by machine gun and rifle fire. The insistent hissing of machine gun bullets and the sharp crack of rifle fire spurred us on until we were under cover once again.

The swaying stretcher with its load was hard to carry, and we collided with the brush and swerved around the many trees until we finally came to the trail and the collecting station, where we turned over our burden to the burial detail.

The daytime hours were generally uneventful. We did take several spells of fire and lost a few men, but they were often passed either visiting or observing the German lines for movement. But the nights were spent watching and waiting for German attacks. On our particular point, though, the marines had made their objective, and we waited quietly for the rest of the line to gain theirs.

Every day at some particular place along the lines there was a raging of rifle and machine-gun fire. The fight was severe, and we were glad that we didn’t have to go up against them. The 49th Company on the 6th of June had lost over 60 percent of enlisted men and 90 percent of officers, and the replacements had not yet brought us up to strength.

We were arranged along the line of battle in groups of three; one night on watch, and two sleeping. During watch, we would pass the word at intervals, “On the alert,” whispering it to the man on the right or left. And beware the man who failed to pass it on.

Our company formed the left flank of the 2nd Division, adjacent to the French forces, and the Germans attacked them one night with a small force. There was quite a flurry of firing of pieces [rifles] and the yelling of French and Germans as they clashed. And it was over about as soon as it started. Then the night’s sky was filled with flares for hours after.

The next night, a platoon from our company was moved over in support of the French; again the Germans attacked and again were driven back. On the third night, a platoon from our company took over that portion of the line, and when the Germans attacked, they gave them the works, and there were no more German attacks at that point.

One night, while I was on alert and all was quiet except for the machine guns, which kept up a continuous chatter, a Sho-Sho gunner on my left started firing. This gun [the Chauchat, the standard light machine gun of the French army in World War I] fires at a rate of about 250 shots per minute, which is relatively slow. It was soon joined by a Hotchkiss, firing at about 400 shots per minute. Then the riflemen adjacent became involved. The fire steadily grew and gradually worked to my position. And so it went down the line for about a mile until all were firing into the darkened void ahead. It was possible to tell every twist and turn of the line from the blaze of weaponry: The air above us was lighted with flares, both German and American, and the German rifles and machine guns also could be heard.

Then company officers and noncoms went running along the line yelling, “Cease firing,” until they got the Sho-Sho and the Hotchkiss stopped, then the men adjacent, and finally the whole line.

All was quiet on our side, but the Germans were unremitting and filled the sky with flares. We were still on edge when the Sho-Sho started again, the Hotchkiss resumed fire, and gradually the fire again extended the length of the line.

The shooting on the left was finally stopped, and the guns gradually grew silent all along the line. The Germans kept the sky well lit with flares the rest of the night, and rifle and machine gun fire was spasmodic from then till daylight.

Just before dawn, Captain [George W.] Hamilton and a group left the lines to investigate what had caused the fire. They returned after daybreak, grinning, each man carrying the spoils of German equipment and also a light Maxim gun. The captain proudly displayed an officer’s No. 9 Luger pistol and holster.

They also found one of our outposts dead, bayoneted in the back. That was what started the show. The Sho-Sho gunner heard the muffled scream of the outpost as he was bayoneted and then cut loose with a burst of fire. It was a real fire hysteria that swept the lines that night, and it affected both Germans and Americans alike.

For a week we held this spot on the top of the hill overlooking “No Man’s Land.” We could not see a soul except for the few men of our own outfit. All life had disappeared from our vista, and only the roofs of the village of Torcy were visible. We could see a huge clock in a tower, which had stopped at 4:20. A shell had vented the tower, and we wondered whether it had stopped in the small hours of the morning or had died in late afternoon.

The only completely visible building was a large red barn on the outskirts of town, near our line. As we watched, we saw a tile or two slither down from the roof. And then gradually there appeared a hole. And we knew German eyes now looked back over to our lines.

We set our leaf sights and carefully aimed a few shots at the hole, but we did not know whether they were effective; only a new hole would appear at some other part of the roof. Officers who watched finally sent word to our artillery, and in a short while the red barn was the scene of action as our shells put new holes in the roof and through the walls of the barn and tore up the ground around it. The red barn itself remained a point of high casualties thereafter.

The only other sign of life was when German stretcher-bearers appeared on the slope before us. They were seen apparently to bear a body, and so not a shot was fired. As they came near cover, the wind lifted the blanket and revealed their burden: a Maxim gun. And from that time on, no German was immune from our fire, and all niceties of warfare were at an end.

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Experience | The Young Warhorse

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!