Thomas entered the wood a promising noncommissioned officer, he left it a proven leader, who would someday rise to the highest echelons of the U.S. Marine Corps.

EAGER TO HAVE U.S. MARINES fight in World War I as part of General John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces, the Marine Corps commandant, Major General George Barnett, successfully persuaded the War Department to accept a marine brigade as part of the token force sent to France in 1917. Eventually organized as the 4th Brigade of the U.S. 2nd Division, it consisted of a brigade headquarters, a machine-gun battalion, and two infantry regiments, the 5th and 6th Marines.

One member of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, was a 21-year-old former football player from Bloomington, Illinois, named Gerald C. Thomas. Like most of his comrades, Thomas volunteered for the Marine Corps in the spring of 1917. Like many of the new marines he also expected to be an officer, since he had completed three years of college at Illinois Wesleyan University, and Commandant Barnett had announced that he wanted college men to be the lieutenants in the expanded corps. Barnett had more officer candidates than openings, however, so Jerry Thomas had to serve first as a corporal and then as a sergeant in the 75th Company until German bullets created sufficient openings in 1918. Before he left the Marine Corps at the end of 1955, General Gerald C. Thomas had fought in three wars and served as assistant commandant and chief of staff of the Marine Corps. His own service reputation, which soared on Guadalcanal and in Korea, began at the Battle of Belleau Wood.

When the German army began its last desperate attempt to win the war on the Western Front in March 1918, it found no Americans except scattered soldiers training with the British. By the end of the spring, General Pershing had committed the four divisions he considered more or less combat ready to the French armies attempting to hold positions north and east of Paris. Late in May, the Germans shattered a mixed Anglo-French force along the Chemin des Dames ridge northeast of Paris, and the 2nd Division joined the French XXI Corps (under Général de Division Jean Degoutte), which was fighting a confused withdrawal north of the Marne River near the city of Chateau-Thierry.

Having had a taste of trench warfare in March, Thomas’s battalion entered its first major battle with some combat experience, but as its officers and men left their camp near Paris by truck on May 30, none of them could have foreseen the ferocious battle that awaited. At the van of the 4th Brigade (under Brigadier General James G. Harbord, U.S. Army—no marine brigadier generals had been immediately available to fill that opening), the 6th Marines moved into an extemporized (and poorly chosen) defensive position anchored on the farming village of Lucy-de-Bocage. From their hastily dug rifle pits, the marines of the 75th Company, 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, looked across the pasture and Wheat field in front of them and saw a thick wood. Sergeant Thomas, by now acting platoon sergeant of the 75th Company’s Third Platoon, certainly had no idea that the wood to his front would prove historic to him and the entire United States Marine Corps.

The following account is adapted from the author’s biography of Gerald C. Thomas, In Many a Strife: General Gerald C. Thomas and the U.S. Marine Corps, 1917–1956, published by the Naval Institute Press.

A DARK FORTRESS OF TALL HARDWOODS, Belleau Wood stretched for about a mile along the edge of a low plateau a few miles from the Marne River. It took its name from the farming village of Belleau, beyond the wood’s northeast corner. Belleau’s only noteworthy feature—a clear, cold spring—gave the town its name (“beautiful water”). Neither the wood nor the town had any importance except that both lay between two major roads that gave the attacking Germans, the IV Reserve Corps, a way to flank the Allied positions along the nearby Paris–Metz highway.

The wood provided an excellent place to assemble an attack force safe from Allied observers. Moreover, German spotters on its western edge could see the marine brigade’s positions around Lucy-le-Bocage. The wood also made an excellent defensive position. Used by a rich Paris businessman as a hunting preserve, Belleau Wood deceived the Americans who watched it from a mile away. Inside the outer edge of trees, it was a tangle of brush and second growth, cut by deep ravines and studded with rock outcroppings and large boulders. Only narrow paths and rocky streams provided access through the wood. Little light penetrated the trees. A haven for game birds and animals, it was meant for hunting by men, not for the lulling of men. In June 1918, however, the 4th Marine Brigade and the German 28th and 237th divisions made Belleau Wood a battlefield.

On the morning of June 3, 1918, General de Infanterie Richard von Conta, commander of the German IV Reserve Corps, ordered a three division attack on the French forces screening the 2nd Division. As the fighting increased, German artillery, assisted by spotters in aircraft and balloons, crashed down upon the marines’ defensive positions. The 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, did not occupy well-built trenches, only quickly dug foxholes. As the shells dropped, shovels and picks rose and fell. Jerry Thomas and the 75th Company soon learned that only a direct hit or a near miss would destroy a foxhole; the 75th pulled the ground around itself and endured. Nevertheless, it suffered casualties: a curious marine was decapitated when he looked outside his hole, two men were knocked senseless by a near miss, a carrying party destroyed on its way forward with water. French soldiers began to drift back through Lucy. To the north, small-arms fire swelled as the first German patrols made contact with a battalion of the 5th Marines defending the woods and high ground west of the Torcy–Lucy road. The 75th Company could hear the noise of troops moving in Belleau Wood.

Soon the French delaying action collapsed, and the only sign of French combativeness was the occasional group of poilus who stayed with the marines. In Jerry Thomas’s position, the Third Platoon gained a Hotchkiss machine-gun crew, a welcome addition since marine machine-gun teams did not arrive until late in the day. The 6th Marines was spread thin, for its commander, Colonel Albertus W. Catlin, had committed three of his four reserve companies to his endangered left flank, where the 5th Marines had first met the Germans. In the late afternoon the 1st Battalion shifted positions to meet an expected attack to its left, which meant that Thomas’s platoon moved from the edge of the village into an open field.

Hardly had the platoon scooped out shallow holes than a German battalion—probably between 400 and 500 men—emerged from Belleau Wood in lines of skirmishers and squad columns and started across the fields toward Lucy. At a range of 400 yards the 1st Battalion opened fire, savaging the German infantry with rapid, accurate rifle fire. The French Hotchkiss crew raked the Germans, and Thomas watched soldiers in baggy feldgrau uniforms spin and slump into the wheat and poppies. The attack collapsed, and the survivors scuttled back into Belleau Wood, where the rest of the 461st Infantry Regiment, 237th Division (about 1,200 officers and men), had concentrated for another attack.

Uncertain about the nature of the new resistance his corps had encountered, General von Conta halted the advance on the afternoon of June 3 and instead continued his assault on the 4th Marine Brigade’s lines with artillery fire. As the heavier German guns and trench mortars moved into range, the marines felt the increased weight of the bombardment. They especially disliked the heavy mortar shells, which they could see curling in on top of them and which detonated with both fearsome noise and destructiveness. Much of the artillery fire, in fact, was now falling on positions to the rear where the Germans guessed—incorrectly—the enemy might have its reserve infantry and artillery positions. The next day (June 4) the infantrymen on either side remained in their holes as German and Allied artillery swept the front with a desultory bombardment. On the left flank of the 6th Marines’ position, a German patrol found a marine’s corpse and identified its foe for the first time. Von Conta shifted to the defense while he awaited the German Seventh Army’s decision on whether the IV Reserve Corps should make another extreme effort to reach the Paris—Metz highway from the north.

Meanwhile, the 6th Marines continued to improve its defensive position by building up its artillery and logistical support. Thomas and two companions were dispatched to map the battalion positions in the sector. The battalion commander, Major John A. (“Johnny the Hard”) Hughes, liked their work—but not their findings. The entire 1st Battalion position had neither adequate cover nor concealment. In fact, Hughes told Colonel Catlin that the entire regiment was exposed and persuaded the colonel to order a withdrawal that night to a reverse-slope defense two miles to the rear.

However, General Degoutte, headmaster of the school of the unrelenting attack, had other plans for the 2nd Division, and a withdrawal was not part of his concept of operations. Degoutte’s XXI Corps was, for all practical purposes, the French 167th Division, the U.S. 2nd Division, and some French artillery regiments, for his other two French divisions no longer existed as effective fighting organizations. At midafternoon on June 5, Degoutte ordered the 167th and 2nd divisions to attack the Germans the next day in order to disrupt the massing of German artillery and infantry reserves in the Clignon River valley north of Torcy. Hill 142, at the left of the line held by the marines, was their first objective. The 2nd Division received a second objective—Belleau Wood—which was to be attacked as soon as possible after the completion of the attack to the north.

The 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, was sent back to a reserve position. Hughes was not unhappy. He did not like the attack plan, a straight-ahead advance like Pickett’s Charge. The 1st Battalion marched five miles to the rear into a protected, defiladed wood near Nanteuil, a village on the Marne. Arriving by daybreak, the marines stripped off their sodden equipment, ate their first hot meal in a week, and collapsed in sleep in the welcome haylofts. In the meantime, the roar of artillery at the front introduced a new phase in the battle for Belleau Wood.

THE 4TH BRIGADE ATTACKS OF JUNE 6, 1918, produced a fury of heroism and sacrifice that remained fixed as a high point of valor in the history of the American Expeditionary Forces and the Marine Corps in World War I. Although Degoutte’s and Harbord’s conduct of operations on that day showed little skill, no one then or now has faulted the marines for their efforts to turn bad plans into good victories. The first mistake was Degoutte’s in insisting that the attacks begin on June 6 rather than a day later, after the attacking battalions had time to enter the front lines, to conduct some reconnaissance, and to make their own analyses of the situation. Artillery-fire support could certainly have profited by the delay. As it was, the battalions had to conduct a relief of frontline positions and also mount an attack within hours after a night movement, no ingredient for success. Moreover, a 6th Marines nighttime patrol had reported that Belleau Wood was strongly defended. This report reached brigade, but it made no difference. The attacks proceeded on the assumption that the German front was lightly held, reinforced by reports that French aerial observers saw little movement in the area.

The early-morning attack on Hill 142, mounted by only two 5th Marine companies, produced a costly victory that widened with the arrival of four more marine companies and supporting machine gunners, who beat back a series of German counterattacks. The action ended around 9:00 A.M. Afterward, General Harbord ordered the Belleau Wood attack to begin at 5:00 P.M. His order reflected an optimism unjustified by the stiffness of the German resistance that morning, for he expected Catlin to take Belleau Wood and the town of Bouresches with only three battalions—perhaps 2,000 men. (Two of these battalions had additional assignments that prevented them from using all four of their rifle companies.) Presumably the fire of 13 Allied artillery battalions would clear the way of Germans. In any event, Catlin mounted the attack as ordered—although Harbord’s concept of “infiltration” changed to a converging standard battalion advance of two companies up, two back—and saw the better part of three battalions shot to pieces by German machine-gun positions along the western and southern edges of Belleau Wood.

From the west, Major Benjamin S. Berry’s 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, barely entered the wood; so few, shocked, and exhausted were the survivors that they could advance no farther. Most of the battalion remained in a wheat field, dead or wounded. The southern attack by the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines, penetrated the wood at sufficient depth to hold a position, but only at great cost. Casualties in these two battalions approached 60 percent, with losses among officers and NCOs even higher. The two-company attack on Bouresches, on the other hand, produced success, even though the two companies also took prohibitive losses. The Germans quickly recognized that the loss of Bouresches menaced their lines of communications, so they counterattacked heavily, thus drawing the rest of the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines (under Major Thomas Holcomb), into the battle. Whatever its original tactical value, Belleau Wood had to be taken in order to protect the left flank of the Bouresches salient.

As he analyzed the scattered reports that arrived at his post of command (PC) during the evening of June 6, General Harbord began to understand that the marine brigade had not taken Belleau Wood and that it had lost more than a thousand officers and men—including Colonel Catlin, who was wounded by a sniper’s bullet while observing the attack. More marines had become casualties in a few hours than the Marine Corps had suffered in its entire history. Although the attacks on Hill 142 and Bouresches had succeeded, the attack on the wood itself had not. Perhaps stung by his own shortcomings as a commander, Harbord lashed out at Catlin’s replacement, Lieutenant Colonel Harry Lee, and demanded the attack be resumed. At that point, Belleau Wood basically remained German except for a corner of its southern edge held by the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines.

As the situation cleared during June 7, Harbord assumed that the 6th Marines could hold Bouresches—with help from the U.S. 23rd Infantry Regiment to its right—so he ordered Lee to continue the attack within the wood itself. His marines fought alone in Belleau Wood, without making much progress. Neither side could mount overwhelming artillery support, since the opposing positions were imprecise and too close; the battle pitted German machine-gun and mortar crews, supported by infantry, against marine infantrymen, who depended primarily on rifles and grenades. Small groups of marines crawled up to the machine-gun positions, threw grenades, then rushed in with bayonets. Few German prisoners survived. The marines ran out of grenades, however, which increased their own casualties. By midmorning of June 8, the battalion had little fight left, and it withdrew from the wood. There were no marines there now.

Harbord let the 2nd Division artillery shell Belleau Wood for the rest of that day, while he organized his next attack. Degoutte had decided that he would not press the attack against Torcy, so Harbord could use his only two relatively unscathed battalions—2nd Battalion, 5th Marines (under Lieutenant Colonel Frederic M. Wise), and 1st Battalion, 6th Marines—for another attack on Belleau Wood. On the evening of the 8th, Harbord ordered Major Hughes to move his battalion into woods southeast of Lucy-le-Bocage. Although the general had not yet committed himself to a particular plan, Hughes believed that Harbord wanted him in position to move into Belleau Wood the following afternoon.

Hughes again sent Sergeant Jerry Thomas on a reconnoitering expedition, this time to locate the mouth of a sunken road that could lead the battalion to the front along a gulley, which would provide cover and concealment. Thomas found the mouth of the sunken road, then jogged back to the battalion. He reported to Captain George A. Stowell, the senior company commander and a veteran of three Caribbean operations, who would move the battalion while Hughes conferred with Harbord at the PC.

The battalion stepped out around 9:00 P.M.—and, in the dark, entered a nightmare of confusion and wrong turns. It did not reach the sunken road until midnight. There, the column met First Lieutenant Charles A. Etheridge, the new battalion intelligence officer. Thomas thought Etheridge knew the rest of the route, but Etheridge had not reconnoitered the trail because Hughes had not told him to do so. As dawn broke, the 1st Battalion strayed into the open fields west of Lucy-le-Bocage and into the view of German observation-balloon spotters. Stowell quickly ordered the men into a nearby wood, where they would have to stay until night came again. Furious, Hughes rejoined his battalion and relieved Stowell of command. (Stowell later returned to the battalion and had a distinguished career.)

Stowell’s 76th Company went to First Lieutenant Macon C. Overton, a thin, handsome, laconic, 26-year-old Georgian who had joined the corps as an enlisted man in 1914. Later in the day (June 9) Harbord ordered Hughes to resume his approach march and to be in position on June 10 to enter Belleau Wood behind a crushing barrage. After dark, the wandering 1st Battalion set off again for the front. This time it did not become lost. On the other hand, it also had nothing between it and the Germans but the outposts of one 2nd Battalion company. The attack on Belleau Wood would have to start again from scratch.

Despite the setback of June 6, Harbord did not change his concept of attack for the June 10 operation. The 1st Battalion would attack the southern part of the wood while the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, would later attack the northern part from the west. The two battalions would join one another at Belleau Wood’s narrow, middle neck. It was a maneuver that looked good on a map, but it worked poorly on the battlefield because of the roughness of the terrain. Fortunately, the extra day of shelling had persuaded the German defenders—still battalions from the 237th and 28th divisions—to concede the wood’s southern edge. But the German combat teams still manned a thick belt of defenses that covered the wheat fields to the west and faced the trails inside the southern woods. The Allied artillery bombardment had taken its toll, but had not crushed the defenders. The Germans endured the intense barrage at daybreak on the tenth and then manned their positions to wait for the next two marine battalions.

Disobeying Major Hughes’s orders to remain near the phones at the battalion PC, Sergeant Thomas joined the waves of marines as they left the woods and started across the lower-lying wheat field for Belleau Wood. The moment had seized him: “The sight of those brave waves moving through the wheat with bayonets fixed and rifles carried at the high post in our first offensive was a little too much to bear.” With two companies forward and two back in the standard French attack formation, the battalion marched steadily across the Lucy—Bouresches road. Rifles at the high port, bayonets fixed, unreliable Chauchat automatic rifles pointed to the front, the marines crossed the swale between the highway and the trees and entered the wood. During the advance, Thomas ran through the wheat until he caught up with the Third Platoon of the 75th Company, avoiding the bodies of marines killed in the June 6 attack. Much to the battalion’s surprise, not a shot was fired at it. Instead of entering the wood, Thomas started back to the PC, for he recalled “that I had another job to do.” He met Hughes, who was elated by the attack and wanted to report his success by phone. The battalion commander did not censure him for joining the attack, but told him to move the PC across the road to the raised bank at the edge of Belleau Wood. As Thomas helped reestablish the battalion PC, he heard the roar of gunfire within the wood. The 1st Battalion had discovered the Germans.

For the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, the battle began around 6:00 A.M. on June 10 and did not end until it left the wood seven days later, an exhausted, smaller, but still combative group of veteran marines. Jerry Thomas fought with his battalion from start to finish. He learned to cope with stress, fear, hunger, thirst, exhaustion, and the death of friends over a protracted period of combat. The fighting on June 10 struck hard at Thomas’s 75th Company, which moved through the wood with Lieutenant Overton’s 76th Company on the left, in the center of the battalion front. When the company struck a strongpoint of three German machine guns, Thomas lost a dozen comrades from the Third Platoon. The marines crawled forward through “a great mass of rocks and boulders,” Thomas later recalled, until they could throw grenades at the machine-gun nests.

Through most of the day, Thomas remained with Hughes at the battalion PC to manage scouting missions and analyze the vague company reports. During the afternoon the regimental intelligence officer, First Lieutenant William A. Eddy, came forward and told Hughes that Colonel Lee wanted an accurate report of the German positions. Taking Thomas with him to prepare sketch maps, Eddy crawled around the woods and quickly learned that no one could see much through the brush. Then, against Thomas’s advice, he climbed a tree. Eddy immediately tumbled from the branches into Thomas’s lap and said, “My God! I was looking square at a German in a machine-gun nest right down in front of us!” Eddy and Thomas returned to Hughes to report that the Germans still held Hill 181, a rocky rise that divided the western and southern wheat fields. Any attack across the western wheat field would still meet flanking fire from Belleau Wood. Having taken 31 casualties in the wood on June 10, Hughes agreed with Eddy’s assessment that one battalion could not clear out the remaining Germans.

General Harbord then committed the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, to the battle, establishing its attack for 4:30 A.M. the next day. Hughes’s left-flank company, Overton’s 76th, was supposed to protect the right flank of Wise’s battalion. Hughes assigned Thomas the job of ensuring that Overton contacted Wise’s battalion as Harbord directed and “conformed to the progress of the attack,” as noted in the brigade attack order. As the rolling barrage lifted, Thomas and one of his scouts left the wood and found Wise’s battalion moving across the same deadly wheat field that had become the graveyard of Berry’s battalion on June 6. Its passage was only slightly less disastrous. As the battalion neared Belleau Wood, German artillery fire crashed down upon it and machine-gun fire raked its front and flanks. Instead of pivoting to the north, the marines plunged straight ahead into the wood’s narrow neck and across the front of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, which had joined the attack, too.

Pressured by his own company commanders for help, Wise asked Thomas where the 76th Company was and why it had not appeared on his right flank. Off Thomas went again, back into the wood. He found Overton, whose company was indeed in action and successfully so. Under Overton’s inspired and intelligent direction, the 76th Company had destroyed the last German positions around Hill 181 and opened Belleau Wood for Wise’s battalion. Overton found Wise’s anger mildly amusing and wondered why the 5th Marines could not use the available cover. Certain that Overton had the situation under control, Thomas returned to Hughes’s PC and told “Johnny the Hard” that the 76th Company had fulfilled its mission.

The two-battalion battle for Belleau Wood became a muddled slugfest, with Wise moving east when he should have been moving north. His battalion engaged the strongest German positions, and suffered accordingly. At one point, Wise, Lee, and Harbord all thought that the marines had seized Belleau Wood. Hughes knew better, but his battalion had its own problems as the Germans responded to the attack with intense artillery fire and reinforcing infantry.

Jerry Thomas continued his duties in Hughes’s PC. Each morning and each evening for the next five days, he checked the company positions and discussed the enemy situation with the battalion’s four company commanders. “On occasion enemy artillery made my journey a warm one.” He helped draft situation reports as well as messages for the regiment, interrogated couriers and occasional POWs, and carried messages himself to the company commanders. Thomas and Lieutenant Etheridge were all the operational staff Hughes had, since the adjutant and supply officer had their hands full with administrative problems. Thomas and Etheridge watched the battalion’s effectiveness wane from lack of sleep, water, and food, and they recognized their own limited capacity. Thirst accelerated fatigue, dulling everyone’s judgment and ardor. “Food was not a problem— there just wasn’t any during our first week in the wood,” he recalled later. The marines stripped all casualties of water and food, then worried about ammunition. Everyone moved as if in a drunken stupor.

In the early morning of June 13, the Germans mounted heavy counterattacks on the marines, punishing positions on the 1st Battalion’s left flank still held by the 76th Company. Macon Overton asked battalion headquarters to investigate the fire to the rear, since he thought it might be coming from the disoriented 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. Etheridge and Thomas, who were reconnoitering the lines, decided to check Overton’s report. Working their way through the wood, which was now splintered and reeking of cordite smoke and souring corpses, they found an isolated 5th Marines company.

The company commander, a young lieutenant named L.Q.C.L. Lyle, told them that he was sure the firing came from bypassed Germans. He had no contact with the company to his left. Etheridge volunteered to scout the gap in the 5th Marines’ lines, but before he and Thomas had moved very far, they saw some Germans who had just killed a group of Wise’s marines and occupied their foxholes. Before the Germans could react with accurate rifle fire, the two marines sprinted back to Lyle’s position and told him about the Germans. Lyle gave Etheridge a scratch squad armed with grenades, and Thomas and Etheridge led the group back through the wood until they again found the German position. In the short but intense fight that followed, the marines killed four Germans and captured a sergeant, who showed them another German stay-behind position, which the 6th Marines attacked and wiped out later the same day. Impressed with Thomas’s performance in this action, Hughes had him cited in brigade orders for bravery in combat.

The German prisoner also provided Thomas with a temporary reprieve from battle, for brigade headquarters wanted to interrogate the POW immediately. Hughes ordered Thomas to escort the sergeant to the rear. When he arrived at the brigade PC, Thomas reported to Harbord’s aide, Lieutenant R. Norris Williams (in civilian life, a nationally known tennis player). Williams asked him when he had last eaten a real meal. Thomas knew exactly: five days. The lieutenant sent him to the brigade mess, where a sergeant who had obviously not been missing his meals fixed Thomas a large plate of bacon, bread, and molasses, accompanied by hot coffee. Food had seldom tasted so good.

Jerry Thomas returned to a 1st Battalion that had reached the limit of its endurance. German shellfire had increased with intensity and accuracy on June 12, continuing through the night and the next day until around 5,000 rounds had fallen on the two marine battalions in the wood. Two company commanders were killed, and one 1st Battalion company, the 74th, was all but wiped out. By the end of June 13, the 1st Battalion had also lost its commander: Major Hughes, staggering with fatigue, his eyes swollen shut from gas, allowed himself to be evacuated. His own condition, however, did not prevent his telling Harbord that his battalion could defend itself, but could no longer advance: “Have had terrific bombardment and attack. I have every man, except a few odd ones, in line now…Everything is OK now. Men digging in again. Trenches most obliterated by shellfire…The conduct of everyone is magnificent. Can’t you get hot coffee and water to me using prisoners?” Before Hughes could receive an answer, he had been replaced by Major Franklin B. Garrett, a 41-year-old Louisianan who had spent most of his 14 years as a marine officer aboard ship, administering barracks detachments, and in Caribbean assignments that did not include combat operations. At the moment, however, the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, did not need a heroic leader. It needed rest.

The effects of sleep deprivation, hunger, and thirst were severe, exacerbated now by gas attacks. The marines fought in their masks, but had to remove them often to clear condensed water and mucous, increasing the chances of inhaling gas. They simply endured burns over the rest of their bodies. The Germans tried no more infantry counterattacks, but they pummeled the battalion with heavy mortars and Austrian 77mm cannon, which fired a flat-trajectory, high-velocity shell dubbed a “whiz bang.” In the meantime, Wise’s battalion (or rather its remnants) and the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines, had finally reached the northern section of Belleau Wood, but could advance no farther without help. The 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, completed the occupation and defense of the southern woods. On June 15 the battalion learned it would finally be replaced, by a battalion of the U.S. 7th Infantry. Two days later, at less than half their original strength, they shuffled out of Belleau Wood.

FOR ALL THEIR EXHAUSTION, THE 1ST BATTALION, 6th Marines, and Sergeant Jerry Thomas had proved themselves tough and skillful during their week in Belleau Wood. After the “lost march” of June 8—9, their performance had been exemplary. Largely because of “Johnny the Hard’s” tactical skill and an extra day of artillery preparation and planning, theirs had been the only one of five marine battalions to enter Belleau Wood without suffering serious casualties. If the 74th Company had not been destroyed by gas and high-explosive shellfire on June 13, the battalion would have fought within the wood with fewer losses than the other marine battalions. Its men also captured their objectives, and never lost cohesion.

Although casualty statistics are difficult to assess then and now, the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, appears to have suffered between 50 and 60 casualties a day on June 10, 11, and 12. On the night of June 12, Hughes reported that he had around 700 effectives. The shelling on June 13, however, cost the battalion over 200 casualties, many of them from gas. Casualties on June 13—15 numbered less than 50. By comparison, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, reported that it had only 350 effectives by the night of June 12, after two days of fighting. Total losses for the two marine infantry regiments (May 31 to July 9, 1918) were 99 officers and 4,407 enlisted men. In the 4th Brigade overall, 112 officers and 4,598 enlisted men were casualties (including 933 killed), more than half the brigade’s original strength.

Although no one could determine which of the infantry battalions med the most Germans in Belleau Wood—from German accounts, Allied artillery probably inflicted the greatest casualties—the 1st Battalion at least shared with Wise’s battalion the claim of destroying the German 461st Infantry Regiment, which had fallen from around 1,000 effectives on June 5 to only 9 officers and 149 men a week later. In addition, the battle of June 10—12 had cost the German 40th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Division almost 800 men killed, wounded, or missing. A battalion from the 5th Guards Division had also fallen to the marines. The 1st Battalion and Wise’s battalion had captured 10 heavy mortars, more than 50 heavy machine guns, and at least 400 prisoners. Within the wood, the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, and 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, broke the back of the German defense, even though the battle did not actually end for another two weeks.

The tactical effectiveness of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines—to which Jerry Thomas had made an important contribution—became obscured by the valor of the entire 4th Brigade in the battles for Hill 142, Belleau Wood, and Bouresches. Paired with the performance of the U.S. 1st Division at Cantigny (May 28—31), the 4th Brigade’s fight proved to the Germans and Allies alike that the AEF would be a significant force in offensive combat on the Western Front. (The 2nd Division’s 3rd Brigade reinforced this conclusion by seizing Vaux on July 1.) The intelligence section of the German IV Reserve Corps filed a major report praising the valor of the marines and predicting glumly that their tactical skill might soon match their heroism:

The Second American Division must be considered a very good one and may even perhaps be considered as a storm troop. The different attacks on Belleau Wood were carried out with bravery and dash. The moral effect of our gunfire cannot seriously impede the advance of the American infantry. The Americans’ nerves are not yet worn out.The qualities of the men individually may be described as remarkable. They are physically well set up, their attitude is good, and they range in age from eighteen to twenty-eight years. They lack at present only training and experience to make formidable adversaries. The men are in fine spirits and are filled with naive assurance; the words of a prisoner are characteristic—WE KILL OR GET KILLED!

French and American headquarters up to and including Pershing’s staff and the French Grand Quartier Général (or Army General Staff) praised the 4th Brigade’s performance. At the emotional level, however, their reactions varied. Pershing and his staff believed that the marines had received altogether too much newspaper coverage, especially for the attacks of June 6 and 11. (The AEF censor was at fault, not the marines.) The French, on the other hand, proved as always capable of the classic beau geste: They awarded the 4th Brigade a unit Croix de Guerre with Palm and renamed Belleau Wood the Bois de la Brigade de Marine. For marines of the 20th century, Belleau Wood became the battle that established the corps’s reputation for valor, and Jerry Thomas had been part of it all.

FOR THE 1ST BATTALION, 6TH MARINES, the battle for Belleau Wood really ended when the battalion returned to the rest area at Nanteuil-sur-Marne on June 17, but it did not leave the sector until the entire division departed in early July. On the road to Nanteuil, the battalion found its kitchens and enjoyed hot stew (“slum”) and café au lait that tasted like a five-star meal. For three days the battalion did little but sleep and eat. The Marne River became a welcome marine bathtub. Ten-day beards and dirt came off; thin faces and sunken eyes took longer to return to normal.

The battalion returned to the Belleau Wood sector on June 20—21 in order to give Harbord two fresh battalions in brigade reserve. The battle in the northern wood had grown as the Germans committed a fresh regiment, and Harbord had countered with an attack by the 7th Infantry and the 5th Marines. After the 5th Marines’ attacks finally cleared the north woods on June 26—Harbord could report accurately, “Belleau Wood now U.S. Marine Corps entirely”—the battalion marched back into the wood, a doleful walk through the clumps of unburied German and American dead. Except for occasional harassing shellfire, the battalion did not have to deal with live Germans, although the smell of the dead ones was bad enough.

Jerry Thomas spent most of his time in the PC or checking the battalion observation posts. His last special duty in Belleau Wood was to help guide the U.S. 104th Infantry, 26th Division, into the sector. Learning that the relieving “Yankee Division” had already lost men to German artillery fire, he once again proved his intelligence and force by persuading an army lieutenant colonel to move the 104th Infantry into the wood by a longer but more protected route than the one the colonel intended to use. Thomas had no desire to add more Americans to the 800 or so dead who were scattered throughout the 6th Marines’ sector.

JUST AS DAWN WAS BREAKING, THE 1ST BATTALION left Belleau Wood for the last time. “Led by our chunky commander, Major Garrett, we traversed the three-quarters of a mile to Lucy at a ragged double time.” Pushing along on his weary legs, Sergeant Jerry Thomas turned his back on Belleau Wood, at last certain that he would never see it again, at least in wartime. The battle, however, had made him a charter member of a Marine Corps elite, the veterans of the Battle of Belleau Wood. From this group the Marine Corps would eventually draw many of its leaders for the next 40 years, including four commandants (Wendell C. Neville, Thomas Holcomb, Clifton B. Cates, and Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr.). On June 10, 1918, Jerry Thomas had entered Belleau Wood a sergeant whose early performance in France had marked him as a courageous and conscientious noncommissioned officer. He left the wood a proven leader of marines in combat, a young man clearly capable of assuming greater responsibilities in the most desperate of battles. MHQ

ALLAN R. MILLETT, a retired colonel of the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, is the Raymond E. Mason, Jr., professor of military history and associate director of the Mershon Center at Ohio State University.

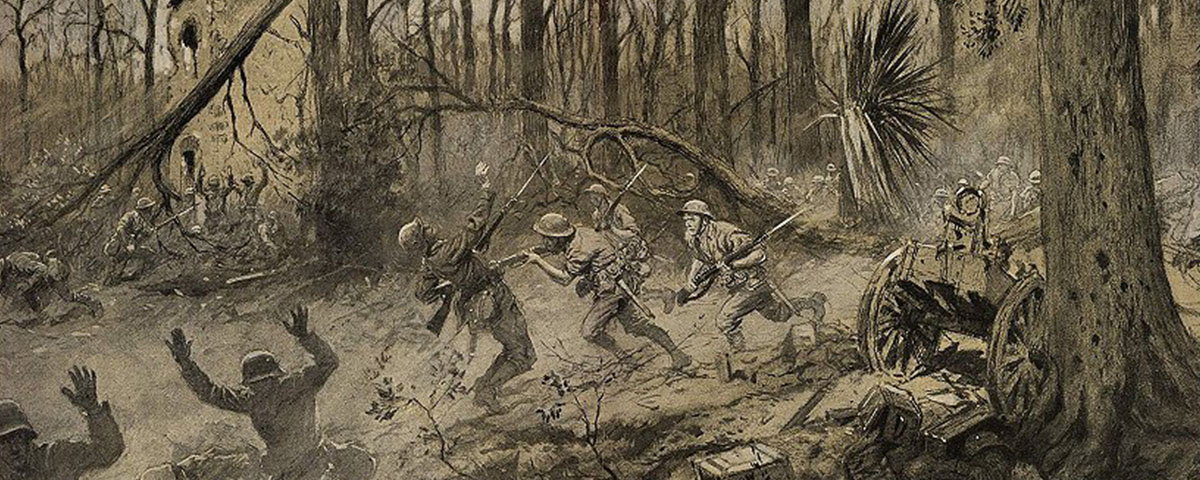

Photo: Georges Scott’s illustration “American Marines in Belleau Wood (1918),” originally published in the French Magazine Illustrations.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 1993 issue (Vol. 6, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Death and Life at the Three-Pagoda Pass

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!