On a gray, wet day in November 1940, Flight Lieutenant Guy Penrose Gibson arrived at Digby aerodrome in Lincolnshire, England. At 22, he was an experienced bomber pilot with 39 operational sorties and the Distinguished Flying Cross to his credit. Gibson was unimpressed at the sight of his new abode—not just because it was set in flat, featureless countryside, but also because Digby was home to No. 29 Squadron, a fighter unit, and bombers were in Gibson’s blood.

He’d had little choice the previous month, however, when his first tour of duty with Bomber Command ended: Either he spent six months as a training school instructor or he volunteered for Fighter Command. Gibson chose the latter; the thought of inactivity frightened him more than the Luftwaffe.

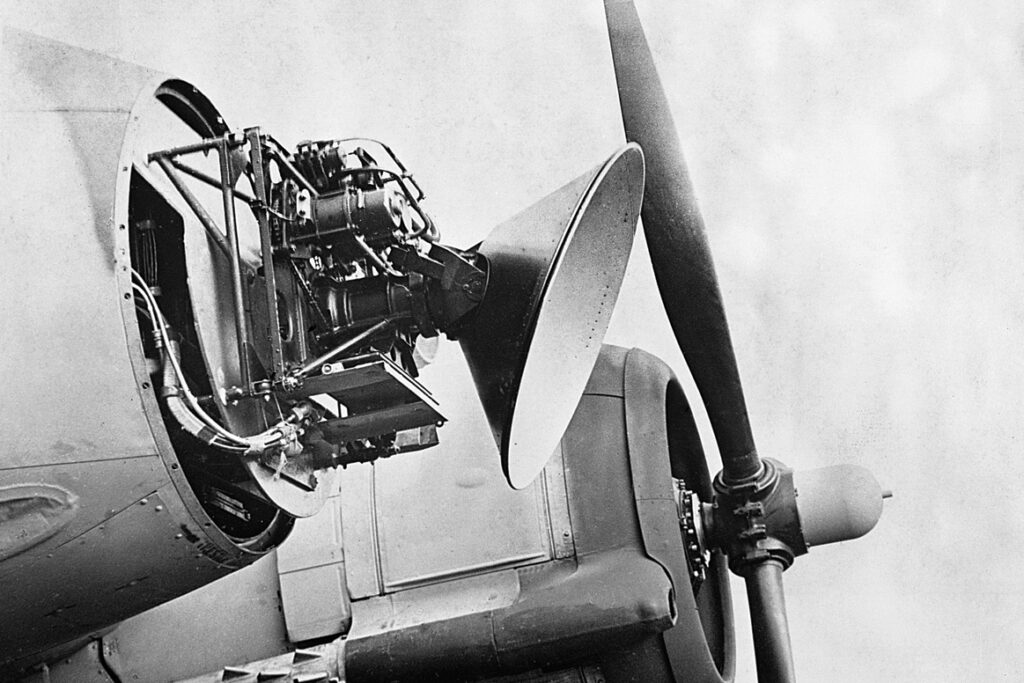

The first member of 29 Squadron who Gibson encountered was the adjutant, Pilot Officer Sam France. Once they’d made each other’s acquaintance, France gave the new arrival a tour of the aerodrome and explained that the squadron was in the process of converting from Bristol Blenheims to Bristol Beaufighters, a two-seat aircraft with a maximum speed of 323 mph and armament of four cannons and six machine guns. It was far superior to the obsolescent Blenheim, said France, who added that the squadron flew day and night.“We operate in all weather [but] things are not going too well at the moment,” he continued. “We haven’t got anything much in the way of control, and airborne intercept devices are not working very well.”

Gibson didn’t have a clue what France was talking about, but decided to worry about that later. He was escorted to the officers’ mess and introduced as the new commander of A Flight. One or two pilots stopped what they were doing to grunt a hello, but most continued reading the paper or playing pool. An uncomfortable silence ensued, broken only by France, who suggested to Gibson that they deposit his belongings in his sleeping quarters and then have a drink at the local pub. Over a pint of beer, France told Gibson to forget his frosty reception: “You don’t want to think that the squadron is bad just because of your first welcome. The trouble is, as you know, that these boys are very browned off; they have been flying since the beginning of the war in Blenheim aircraft, never shooting anything down, and watching all the other squadrons get the gongs.” France also explained that Gibson’s predecessor in A Flight had been popular, but that he shouldn’t worry; in time he’d win their respect.

Gibson didn’t worry. He wasn’t the sort of man to give a hoot what others thought of him. Instead he set out to master his new aircraft so he would be the best pilot in 29 Squadron. Gibson found much to dislike in the Beaufighter aside from the fact that it didn’t even have cockpit heating (that would come later). It was “very heavy and its wing loading rather on the high side,” he reflected, although unlike some of his contemporaries he didn’t find that it stalled too quickly or was unmaneuverable in tight turns. While he was impressed by the airplane’s armament, he soon discovered that the cannons and machine guns had a nasty tendency to jam.

While Gibson familiarized himself with the Beaufighter, the squadron’s non-commissioned officers were learning how to use its greatest innovation, what Sam France had referred to as the “airborne intercept devices.” This was in fact the latest in aircraft radar, the Mark IV, vastly superior to the Mark III that had been fitted in the Blenheims. The new radar system had a more powerful transmitter that gave it greater range, and its receiver was also an improvement over the Mark III’s, making it possible to track enemy aircraft to a minimum range of 140 yards. There was genuine excitement in the Royal Air Force that the Mark IV, in tandem with the Beaufighter, would give pilots the edge over the Luftwaffe in night fighting.

One of those learning the newfangled radar system was Richard James, a tall, athletic sergeant from the north of England. Born on Christmas Day 1911, James had been a manager in a construction company before the war. He had volunteered for the RAF because he didn’t want to be drafted into the army. After his initial training, James was posted to 29 Squadron and fought in the Battle of Britain as a radar operator in a Blenheim, an aircraft that he remembered as “horrible.” When the squadron converted to Beaufighters and upgraded its radar to the Mark IV, he was asked to train new radar operators on the system.

“The Mark III was very unreliable and had a limited scope,” James recalled. “And because the Blenheim wasn’t as fast as the aircraft we were trying to shoot down we had no success. But it was clear pretty quickly that things would be different with the Mark IV and the Beaufighter. One of the best differences was that in the Blenheim the radar was on the floor, so we had to kneel to operate it, whereas in the Beaufighter we could sit on a cushioned swivel-seat and look through a visor at a screen in front of us. What a luxury!”

It was a bewildering experience for recruits when they looked through the rubber visor for the first time and began to turn the control knobs. On the screen were two luminous green cathode tubes, one vertical and the other horizontal. The radar emitted a series of radio signals, and if an aircraft was within range an echo bounced back, materializing on the green lines as a cluster of sparkling lights known in RAF jargon as “blips.” As James explained to his trainees: “If the [enemy] aircraft climbed higher the blip on the vertical tube got bigger so the operator told the pilot to climb. From the blip on the horizontal tube you could see if the aircraft was port or starboard.”

Once the radar operator knew this, he guided his pilot via the intercom (a catwalk separated the pilot from the radar operator behind him) toward the target until the blips sat squarely across the tubes. Now they were within 140 yards of the enemy, and the Beaufighter pilot would be able to see the exhaust flames of his unsuspecting prey.

Recommended for you

When Gibson was commissioned to write his wartime memoirs in late 1943, shortly after he had been awarded the Victoria Cross for commanding the famous “Dambuster” raid that May, Britain’s radar system was still so secret that he was only allowed to make the vaguest allusion to what had gone on at 29 Squadron three years earlier. “Yet another innovation had been devised by the scientists,” he wrote in Enemy Coast Ahead. “This was a very secret weapon which cannot be described in full until after the war, but roughly, it consisted of two teams—a pilot and the observer. It was the pilot’s job to fly carefully on instruments, while the observer sat in the back twiddling knobs and working dials, picking up the bandit ahead.”

Throughout December 1940 and January 1941, 29 Squadron mastered the Mark IV radar, with pilots often taking up three operators for an hour’s instruction each. “At first the operators, as they were called, seemed to have no idea at all,” wrote Gibson.“But we all had to be very patient and after a time some of them began to get very good.”

Strong working relationships formed, and pilots and operators paired off until Gibson was about the only officer without a partner. When Sergeant James received a visit from him in early February 1941, he was more than a little surprised. Not only had they not flown together, they’d never even exchanged a word in the three months Gibson had been with 29 Squadron.

“He asked me if I’d like to fly with him on a permanent basis,” said James. “He didn’t say why he wanted me, only that he needed to team up with someone and would I like the job. Two thoughts sprang into my mind when he asked me: first, that he obviously thought I was a decent operator, and secondly, that I stood a better chance of living longer flying with Guy Gibson than anyone else.”

Though Gibson had asked James to be his radar operator, it was clear the relationship was purely professional. Gibson had by then earned the respect of his air and ground crews alike, but there was little affection for a man who was not an extrovert by nature. In addition, Gibson had married shortly after arriving at 29 Squadron, and when he wasn’t on duty he spent his free time with his wife.

“When I first started flying with Gibson I just couldn’t get through to him,” recalled James. “My nickname in the squadron was ‘Jimmy,’ but he called me James, and he never asked anything about my family. I couldn’t understand it because all the other crews, regardless of rank, were on first name terms. I got to the stage where I just went along with this, mainly because I was in absolute awe of him, and because he scared the shit out of me!”

Gibson might have terrified James with his disregard for danger, but the radar operator had never seen such a skilled pilot. While other pilots complained of the Beaufighter being difficult to manage, Gibson could pull off a three-point landing. And when they were patrolling the night skies, waiting to see if the Luftwaffe would materialize, Gibson practiced flying on one engine. “One time we did actually lose an engine over the North Sea,” recounted James. “We radioed ahead to warn the base we were returning on one engine, and as we approached the aerodrome we could see ambulances and fire engines. But we landed without a problem, and later on in the sergeants’ mess someone said to me, ‘That was a dodgy do earlier, wasn’t it?’ I just laughed and said‘not at all,’ explaining that we’d been practicing flying on one engine for weeks. Gibson really was an exceptional pilot.”

But James’ devotion to Gibson wasn’t blind. Much as he admired his pilot’s flying abilities, he recognized his shabby social skills. Gibson had at last begun to address James with the more informal “Jimmy,” but he maintained his aloofness elsewhere. “I think he invited a lot of unpopularity,” reflected James. “He would come down after a flight and walk past his ground crew without saying a word to them. At first I used to do the same but then I thought ‘bugger this!’ and I started to chat to them, particularly when we’d been in action because they wanted to know all the details.

“But you have to remember he was very young for a flight commander, and he had to impose himself, and that was the way he did it. And I think it’s true to say he had an inferiority complex because of his size [Gibson was 5 feet 6 inches, five inches shorter than James].”

The weather over Britain in early 1941 was exceptionally bad, with low-lying cloud cover restricting German air attacks, but in March the skies cleared and the Luftwaffe began to return. Now 29 Squadron was ready for the German raiders, and Squadron Leader Charles Widdows soon claimed the unit’s first confirmed kill when he shot down a Junkers Ju-88 on March 12. Another pilot destroyed a Dornier Do-17 a few hours later, and the next night it was Gibson and James’ turn. Patrolling the North Sea over the eastern coastal town of Skegness, James picked up an aircraft on the radar and guided Gibson onto its tail. When they identified it as a Heinkel He-111, Gibson prepared to attack.“I knew he hadn’t seen me but I could see him clearly—a black smudge against the stars,” he described in Enemy Coast Ahead. “I adjusted my parachute harness and safety straps, then carefully turned on my ring sight and closed for the attack. When the centre spot was right in the middle of the Heinkel I pressed the button…instead of a blinding flash there was nothing.”

Gibson swore, then throttled back to avoid overshooting as the Heinkel flew on, oblivious to the mortal danger on its tail. Once more the Beaufighter maneuvered into a firing position, but this time only one cannon fired. Gibson was confident he’d killed the rear gunner; nonetheless, he screamed over the intercom for James to clear the blockage. “Clearing cannons at 17,000 feet without oxygen wasn’t easy,” noted James. “But eventually I cleared the jam in one cannon and then promptly collapsed from exhaustion.”

James had done his job, allowing Gibson to pursue the fleeing Heinkel east across the North Sea. He opened fire, and “as shell after shell banged home there was a yellow flash. Sparks flew out and the engines stopped.” Gibson watched the aircraft crash into the North Sea just off the coast. That afternoon he motored out to Skegness with James to collect the Heinkel’s tail assembly as a squadron trophy.

By April 1941 there was a further innovation in the radar defense system: ground control interception. From a string of coastal stations, controllers were able to guide RAF fighters to within three or four miles of enemy aircraft before handing over to the radar operator thousands of feet above them. Gibson described a typical series of instructions in his memoirs:

“Hello, Bad Hat 17 [Gibson’s call sign]. This is Digby Control. Bandit approaching you from the east. Vector 09 zero, angels fifteen [one angel equaled 1,000 feet of altitude, so 15,000 feet], about ten miles away.”

A little later:

“Hello, Bad Hat 17. Bandit three miles from you. Prepare to turn sharp to port on 270 degrees. Angels ten.”

Then would come the order to turn, and with full throttle the Beaufighter would swing around in a vertical turn and wait for further instructions. Then:

“Hello, Bad Hat 17. You turned rather late. He is now about four miles ahead and slightly to port. Vector 425 for two minutes then back on to 280 degrees.”

At the end of April 1941, 29 Squadron moved south to West Malling aerodrome in Kent. Almost immediately they were in action, as the Luftwaffe launched a series of heavy raids against the port of Liverpool in the first week of May. To reach the target in the northwest of England, the German bombers had to fly across Kent, providing the RAF with rich pickings.

The Beaufighter crews of 29 Squadron met with considerable success, including Gibson and James, who claimed their second kill on the night of May 3-4. They watched the enemy aircraft—a Ju-88—fall to earth in flames in silence without any sense of elation. “When you got a ‘blazer,’ when everything burned straight from the word go, well, you knew there were six blokes in that Heinkel being roasted to death and that’s a bit sad,” reflected James. “But we didn’t dwell on it much, I didn’t at least. I do remember once though, when I was home on leave, being asked by my aunt, ‘How do you feel about killing people?’ I was damned annoyed at her for asking that question.”

On May 10, the Luftwaffe launched its heaviest raid on Britain to date, 400 bombers attacking London in an assault that left 1,436 dead. It turned out to be the last raid of the Blitz, as the German air force began heading east to prepare for the invasion of Russia. Not that 29 Squadron knew any of this in the early summer of 1941. After the excitement of the spring, early summer was a mundane period, involving a lot of fruitless patrolling up and down the French coast.

By then Gibson and James had been brought closer through their shared experiences. James was invited by his pilot for pints in the pub, and they enjoyed playing practical jokes on one another. Gibson’s sense of humor, however, wasn’t always to his operator’s taste. “One time we were patrolling the French coast off Dunkirk when Gibson started getting bored,” remembered James. “The Germans had a massive searchlight there that appeared—at least to me—to be so powerful that it lit up the cliffs on our side. I said this to Gibson over the intercom, and he agreed. Then he said mischievously, ‘Shall we put it out?’

“What could I say? If I’d said no, he’d have thought I was chicken, which I was, so instead I said,‘Go on then’! So we went into a dive and nothing happened. Even when we were right on top of this searchlight nothing happened because they must have thought we were one of theirs. And then Gibson opened up on this bloody great searchlight with four cannons and six machine guns, and the stuff that came back was pretty grim. But by now we were so low that it was up above us and we were quite free. We made a sharp turn to port, keeping low, and came away without a scratch. Gibson thought it was great but when we got back he got a rocket [from the squadron CO] for endangering his craft and his crew, which pleased me!”

But James described the posthumous image of Gibson as a man without fear as wrong: “We picked up a Dornier once [in April 1941] and opened fire. We knew we hit it because pieces came off it, but the rear gunner fired back and this was the first time we’d received any return fire. To my surprise Gibson turned away. When we landed he wrote in the logbook: ‘Returned fire, very accurate, quite frightening.’ That was the first time I realized Gibson had some fear; he was just able to control it.”

Once news broke of Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union, 29 Squadron was tasked with intercepting German aircraft laying mines in the North Sea to disrupt British shipping heading to Russia. On July 6, Gibson and James claimed their third confirmed kill, a Heinkel that crashed in the sea off Kent.

It was their last victory together. Gibson, who had won a bar to his DFC (James was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal), left 29 Squadron for an officer training unit in the winter of 1941, an appointment that fortunately for him was short-lived. In March 1942, he was appointed wing commander of No. 106 Squadron, a bomber unit flying Avro Manchesters and later Avro Lancasters. In the next year, Gibson flew 46 missions before being appointed to command the new No. 617 Squadron and lead it in breaching the Möhne and Eder dams. Later he traveled to the United States on a lecture tour (during which he was presented with the Legion of Merit by President Franklin D. Roosevelt) before returning to operational duties in 1944. On September 19 of that year, having completed more than 200 operational sorties in five years, Gibson flew a Pathfinder mission for a bombing raid on Rheydt, Germany. He and his radar operator, Squadron Leader James Warwick, were killed when their de Havilland Mosquito crashed near Steenbergen, in the Netherlands.

James, by then a flight lieutenant, learned of Gibson’s death while serving with No. 96 Squadron. “I wasn’t surprised at all because he knew he would not survive the war,” said James. “Gibson was always talking about the statistics [of surviving]. He used to look at the picture as a whole. He was no mug; he knew the losses that took place in Bomber Command.”

When I interviewed James in July 2004, the 60th anniversary of Gibson’s death was approaching, but the esteem in which he held his former pilot remained undimmed. “I couldn’t have been treated with more respect than I was by Guy Gibson,” he said. “I saw him tear people off a strip, bully them, but he treated me with absolute respect. The thing with Gibson was that he expected everybody to put in the same effort as he did.”

Gibson allowed few airmen to get close to him during the war, but James was privileged to have known him better than most. And of all the memories James had of Gibson, one stood out in particular: “There was a squadron party in the sergeants’ mess shortly before Gibson’s departure to which we’d invited the officers to come along afterwards. Gibson and I were both up at the bar, having had quite a lot to drink, when Gibson turned to me and said,‘Jimmy, we’ve got to the stage now where if any [German airplane] comes over we’re pretty damned sure to shoot it down.’ I agreed and then he leaned back against the bar and said, ‘Ah, yes, it won’t be long before we’ll see our names on the front pages of the paper!’”

As far as he was concerned, Gibson was right. Within two years his was indeed a household name, another addition to the pantheon of British military heroes, one whose raw courage was complemented by scientific progress. As Gibson said of his year with 29 Squadron: “This was the twentieth century war, the war of electricity.”

Gavin Mortimer is a British writer who contributes regularly to BBC History Magazine and World War II. He is the author of Chasing Icarus: The Seventeen Days in 1910 That Forever Changed American Aviation and The Blitz: An Illustrated History. For further reading, he recommends: Enemy Coast Ahead, by Guy Gibson; and Dambuster: The Life of Guy Gibson VC, by Susan Ottaway.

Originally published in the January 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.