As a red flare curved into the Lincolnshire sky, the engines on 19 Avro Lancasters clattered to life and the black bombers began to move slowly out of their dispersals. The muffled roar that evening, May 16, 1943, was familiar to nearby residents. Operations were on again. RAF Scampton’s aircraft would likely be joining hundreds of others in another “maximum effort.” Where are our boys going tonight: Berlin? Hamburg? Some would offer a silent prayer for their safe return.

The new squadron was in fact setting out, by itself, on one of the most remarkable missions of the war, using a unique new weapon. The operation was so secret that not even the ground crews, who had loaded the huge cylindrical objects under the fuselages that earned the planes the nickname “Scampton Steamrollers,” knew where they were going.

At 9:28, Bob Barlow, one of many Australians serving with Bomber Command, pushed the throttle levers fully forward, then moved his hand aside for flight engineer Sam Whillis to hold them in position. With such a heavy fuel and bomb load, any loss of power on takeoff would be disastrous. As the Lancaster gained altitude and the airfield disappeared behind his turret, rear gunner Jack Liddell would have breathed a sigh of relief. Just 18, he had falsified his age two years earlier to join the Royal Air Force, and was already a veteran of 30 missions when few bomber crews survived half that number.

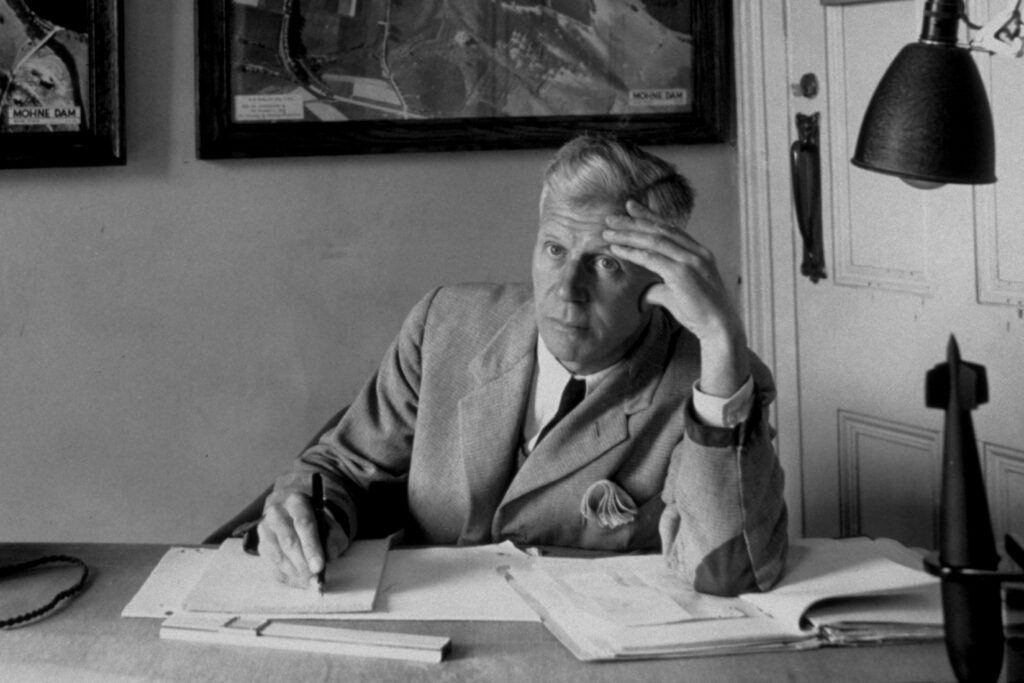

At the RAF’s No. 5 Group headquarters, Barnes Neville Wallis faced the longest night of his life. As assistant chief designer for the armament firm Vickers Armstrongs, he had conceived the mission plan. His research had shown that to produce each ton of steel, the Germans required thousands of gallons of water from several great Ruhr valley dams, the largest being the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe. Coal and armament production, hydroelectric power and cities also depended on these sources. The largest conventional bombs would barely chip the concrete dams, assuming they could hit them from 20,000 feet. But, Wallis theorized, detonate enough high explosive in contact with the dam wall and the water would magnify the force, in the same way a torpedo with a relatively small explosive charge could sink a battleship.

The paper he sent to leading scientific, government and military personnel, complete with formulas and calculations, produced either ridicule or indifference. It also resulted in a visit from a Secret Intelligence Service agent, who wanted to know why Wallis was sharing “vital and very secret” information. “Is it?” he replied. “When I showed it to the authorized people they said I was mad. I’m supposed to be a crackpot.”

Years later, he discovered another possible reason for resistance to his ideas: He had been on a list of potential enemy agents. Inventors in the pay of the Germans, the theory went, would submit ideas to scientific branches of the services and from their reaction deduce what was already being worked on.

The government had earlier formed the Air Attack on Dams Committee, which concluded “an attack on the Möhne Dam is impracticable with existing weapons.” Wallis pleaded, “Give me time to find out how much RDX will blow a hole in the Möhne if it’s pressed up against the wall.” A 279-pound charge of the powerful new explosive destroyed a small, disused dam in Wales, from which he calculated that 6,000 pounds would punch a 50-foot breach in the Möhne. The total weight of such a mine would be less than 5 tons, which the four-engine Lancaster could easily carry to the Ruhr. But the problem of how to avoid torpedo nets guarding the dams and place the mines deep against the wall remained unanswered.

Recalling that Admiral Horatio Nelson had sometimes attacked French warships by skipping cannonballs off the sea, Wallis experimented by catapulting marbles off water in a bathtub, and then from a boat on a nearby pond. From tests on larger projectiles at the Teddington ship research laboratory, near London, he calculated the distance a mine should be dropped from the dam, at what height and speed, and how much backspin would cause it to skip on the water and help it cling to the dam wall as it sank.

On December 4, 1942, with Vickers test pilot Captain “Mutt” Summers at the controls and Wallis in the bombardier’s position, a modified Wellington approached the bombing range with a full-size inert mine slung beneath. Naval gunners, unable to identify the aircraft with its great bulge, opened fire, which Wallis considered “carrying official obstructionism a little too far.” As the aircraft leveled off, he pressed the release. To the gratification of skeptical observers, the mine broke apart upon hitting the water, as did subsequent ones. Finally, in January 1943, a mine with a strengthened casing skipped 20 times, covering 1,315 yards.

In mid-February, Bomber Command’s Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, concerned that RAF resources would be diverted for Wallis’ scheme, wrote to the chief of the Air Staff, Charles Portal, that “the weapon itself exists only within the imagination of those who conceived it,” and called it “just about the maddest proposition as a weapon that we have come across.” When Wallis met with Harris on February 22, the air chief marshal’s reaction was hardly encouraging. “I’ve no time for you damned inventors,” he growled. “My boys’ lives are too precious to be wasted by your crazy notions!” However, after watching films of the model tests at Teddington and the successful full-size drops, Harris agreed to think about it.

The next day Vickers’ chairman summoned Wallis, telling him he’d been making a nuisance of himself and should stop further work on the project. Shocked, Wallis offered to resign. But just three days later, after Air Chief Marshal Portal overruled Harris’ objections, the inventor was again summoned and told, “Orders have been received that your dams project is to go ahead immediately with a view to an operation at all costs no later than May” (when the lakes would be full). It meant less than three months to perfect the mines, modify the planes and create and train a new squadron to do what had never been done before.

On March 14, 24-year-old Wing Commander Guy Gibson landed after a harrowing mission to Stuttgart. An engine in his Lancaster had failed soon after takeoff, and with an 8,000-pound bombload the aircraft could not maintain altitude. Gibson pressed on, and with the three good engines shaking the Lancaster at full power, bombed the target at low level. It was his 173rd mission and completed his third tour, a monumental achievement when few of his contemporaries lived to finish one. Now he could look forward to enjoying leave in Cornwall.

Instead, he received orders to report to Air Vice-Marshal Ralph Cochrane, 5 Group commander, who first congratulated him on the award of his second Distinguished Service Order (he already held the Distinguished Flying Cross). Cochrane then asked, “How would you like the idea of doing one more trip?” Thinking of the flak and fighters he hoped to avoid for a few weeks, Gibson hesitantly replied, “What kind of trip, sir?”

“A pretty important one, perhaps one of the most devastating of all time,” said Cochrane. Three days later at another meeting the air vice-marshal told him that a special squadron was to be organized for the job. “I want you to form that squadron,” he said. “As far as aircrews are concerned, I want the best—you choose them.” Gibson selected 22 highly experienced crews from Britain, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. And the U.S.: 6-foot-3-inch “Big Joe” McCarthy and Henry “Dinghy” Young, so nicknamed because he had twice been picked up from his rubber raft after being shot down.

Gibson addressed the men: “You’re here to do a special job, you’re here as a crack squadron, you’re here to carry out a raid on Germany which, I am told, will have startling results. Some say it may even cut short the duration of the war. What the target is I can’t tell you. Nor can I tell you where it is. All I can tell you is that you will have to practice low flying all day and all night until you know how to do it with your eyes shut.”

In the days that followed, the new No. 617 Squadron’s crews gleefully flew across Britain at previously forbidden hedge-hopping heights, buzzing towns and villages, down rivers and out to sea. As complaints flooded in, Gibson tore them up.

Wallis couldn’t even tell Gibson, who was to lead the raid, what the target was, as the wing commander was not on the list of those permitted to know. He did show Gibson the films of his successful drops from the Wellington. “Well, that’s my secret bomb,” he said. “That’s how you’re going to put it in the right place. Now, can you fly at 240 miles per hour, at 150 feet, over water?”

Gibson took his crew to practice over Derwent Water, a lake and dam in Derbyshire resembling the Möhne. It proved difficult by day, and impossible in the dark, to dive over the surrounding hills and level out at the right height. Once they nearly went into the lake and bombardier “Spam” Spafford said, “This is bloody dangerous!” The solution was to fit two spotlights under each plane, aimed to converge at 150 feet. Crews now found they could fly at night to within 2 feet of that altitude. More sobering was the fact that a Lancaster, flying straight and low and shining spotlights, would be a prime target for anti-aircraft gunners.

Cochrane showed Gibson scale models of the dams, the first time he knew what they would be attacking. “You’ll be the only one in the squadron to know,” Cochrane said. “Keep it that way.” But three weeks from the raid’s scheduled date, mines continued to break up on hitting the water; 150 feet was too high. “Can you fly at 60 feet above the water?” Wallis asked Gibson. “If you can’t, the whole thing will have to be called off.” A Lancaster’s wingspan was more than twice that distance. At that height, Gibson thought, you would only have to hiccup and you would be in the drink, but he told Wallis, “We’ll have a crack at it tonight.” On April 29, a mine dropped from 60 feet worked. The aircrew could see, down on the beach, a white dot bobbing about—Barnes Wallis waving his cap and dancing in the pouring rain.

May 16 had been a fine, sunny day. The hectic mission preparations were complete. At a final briefing by Cochrane, Gibson and Wallis, the aircrews were shown scale models of their targets, and enjoyed the rare treat of a bacon and eggs meal. Some, with uncanny premonition, wrote final letters to their next of kin or said goodbye to friends in other crews. The previous night, Gibson’s black Labrador, who often flew with him, had been run over and killed: a bad omen. He ordered his pet to be buried at midnight, feeling that at that moment, at the raid’s height, he might well be joining his faithful friend. More encouraging was the assigned identification, AJ-G, for his aircraft. They were the initials of his father, whose birthday it was.

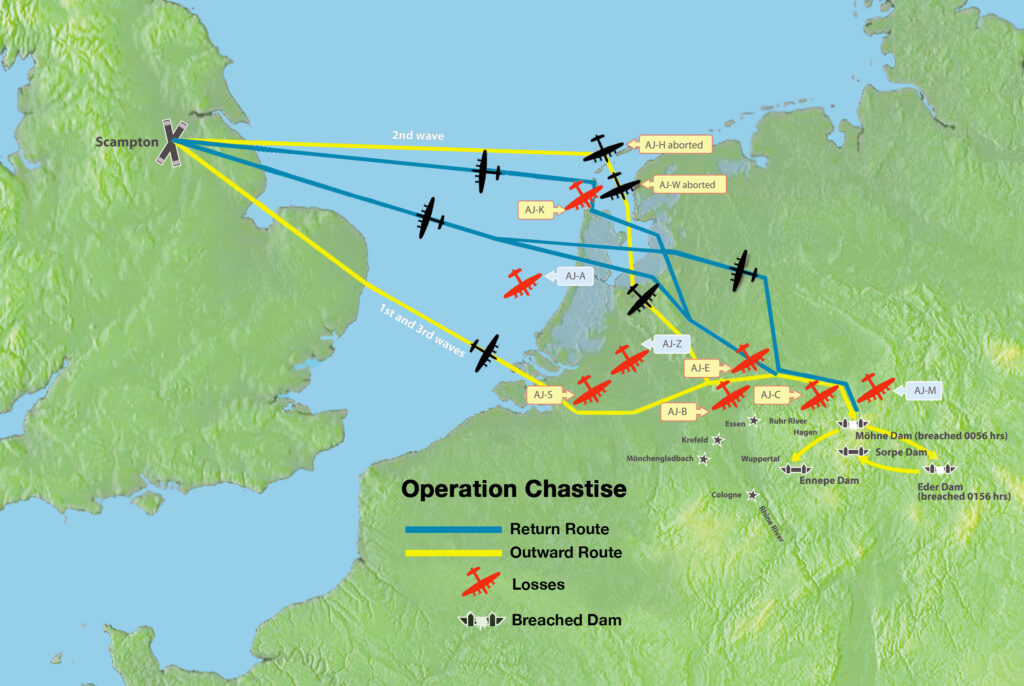

Finally the time came to take off. Gibson’s wave of nine Lancasters would attack the Möhne. Once it was breached—if he survived—he would lead the aircraft that had not yet dropped their mines to the Eder. A separate wave of five planes would attack the Sorpe. Five reserves would bomb any targets not destroyed.

Crossing the North Sea at 60 feet, aided by the spotlights, they climbed to 1,000 feet over the Dutch coast, then down again, low enough sometimes to pass under high-tension cables. With 40 minutes to go to the Möhne, several aircraft had taken flak damage. An engine on John Hopgood’s AJ-M was knocked out, and Hopgood, rear gunner Tony Burcher and wireless operator John Minchin were wounded. At 10:57, Vernon Byers’ AJ-K, in the second wave, was hit and crashed in the Waddenzee. Soon Bill Astell’s AJ-B was also lost. Barlow’s AJ-E, the first to take off and carrying rear gunner Jack Liddell, crashed 13 minutes later. Its mine was recovered intact by the Germans, who unsuccessfully attempted to copy it as an anti-ship weapon. Three down.

At the Möhne, Gibson thumbed his transmitter: “I am going to attack. Stand by to come in to attack in your order when I tell you.” As his Lancaster sped across the lake, its two .303-inch forward machine guns engaged in an unequal duel with the dam’s battery of 20mm cannons, whose gunners wondered why the crazy British apparently had their landing lights on. With tracers whipping past, Gibson yelled to his flight engineer, “Stand by to pull me out of my seat if I get hit!”

Spafford shouted “Mine gone!” and they rocketed over the dam. Gibson banked to see a gigantic white plume rise from the black waters. When it subsided, the dam was still there. Hopgood, wounded in the head earlier, attacked next. Shells hit a wing, and the mine fell away late, exploding on the power station. Trailing fire, the Lancaster struggled for altitude as Hopgood yelled to his crew, “For Christ’s sake get out!” Minchin, his leg nearly severed in the earlier flak strike, crawled to the escape hatch. Without telling Hopgood, he had continued at his post with this terrible wound. Burcher clipped Minchin’s parachute on and pushed him out, then he and bombardier Jim Fraser followed. They were two of only three who became POWs out of the 56 of 133 airmen who did not return. (Minchin died from his wound.)

“Mick” Martin bombed next, but a hit in the wing caused him to swerve, and the mine exploded short of the dam. With Gibson flying alongside to attract flak, Young attacked, his mine exploding on the parapet. Still the dam held. David Maltby, with Gibson and Martin flying on each side, bombed accurately, and a few seconds later Martin’s voice filled their earphones: “Hell, it’s gone! It’s gone!” The lake water was crashing through a 100-yard gap. Burcher, lying in a field, his back injured, heard the roaring water.

Wallis received the news with mixed feelings—elation that the first target had been destroyed, disappointment that it had taken four mines. (Gibson’s probably exploded on the anti-torpedo nets, blasting a hole for Maltby’s, the only one to hit the dam’s center.)

On to the Eder. The lake was long and winding, rimmed by sheer, tree-lined hills, requiring a steep corkscrew dive with only seconds to level out, adjust altitude and speed and drop the weapon, then a maximum-power climb to avoid hills on the other side. Flying a big Lancaster in the dark and a gathering mist, it was incredibly difficult and dangerous. After six attempts, Henry Maudslay and Dave Shannon could not get their height and speed right in time to bomb. Finally Shannon succeeded, and the familiar geyser of spray rose at the dam wall.

Maudslay came in too fast, the mine exploding on the parapet as his bomber flew over. He managed to nurse the damaged Lancaster, AJ-Z, for several miles before becoming a flak victim. On his fourth try, Les Knight, in the remaining plane, dropped his weapon, which bounced three times and hit. Once again the surviving crews watched in awe as a roaring torrent exploded out of the breach. They could see the lights of vehicles, desperately trying to escape, turning green as the water rolled over and snuffed them out.

Unknown to Gibson or those at Scampton, of the five aircraft assigned to the Sorpe, only Joe McCarthy’s got beyond the Dutch coast. The others, together with most of the five reserves, had been shot down, hit power lines or returned with equipment problems. Gibson, and Control in England, called Astell, Barlow, Byers, Louis Burpee and Warner Ottley several times, but they were all dead. (Freddie Tees, Ottley’s rear gunner, had a miraculous escape. Blown clear when AJ-C crashed and the mine exploded, he became the third and last POW survivor.) McCarthy and reserve pilot Ken Brown bombed the Sorpe dam, but, unlike the masonry Möhne and Eder, it was a massive earth structure with a concrete core. Wallis had hoped tremors from several mines would start leaks that would widen and cause it to fail, but two explosions proved insufficient.

Eight tons lighter in bombs and fuel, the 10 surviving Lancasters hugged the ground at 260 mph in a race to get home. The coast was an hour away, and dawn was breaking. Several bombers suffered further flak damage. Young radioed that he was ditching yet again. After 65 missions his luck finally ran out; this time he was not in his dinghy.

Wallis met the survivors at Scampton. When the extent of the losses became clear, he was distraught, saying, “If I’d only known, I’d never have started this.” Martin took him aside and explained that seeing sudden death was nothing new to the men of Bomber Command, and few had expected to survive the war. It could have been worse: There were no losses to enemy night fighters. A communications breakdown had caused the nearby German base at Werl to continue its night flying training. Other fighters were unable to locate the incoming and outgoing aircraft at their extremely low altitude.

The Ruhr valley, which had been enduring a trial by fire, now experienced one by water. Roaring torrents, racing at 50 feet per second, swept away buildings, power stations, high-tension lines, bridges and railroad viaducts, including the ones carrying the main Dortmund and Frankfurt lines. Factories in Gelsenkirchen, Dortmund, Hamm, Essen, Bochum and beyond were destroyed or damaged; many others had no water or electricity. Fifty miles away, coal mines and airfields were inundated. The industrial area of Kassel was underwater. Canal banks were washed away, and barges—crucial conduits for coal, munitions and aircraft parts—sat grounded on the bottom. Steel production was affected for the rest of the year.

The official German report called it “a dark picture of destruction,” and estimated it was equivalent to the loss of production of 100,000 men for several months. Armaments minister Albert Speer was confident that German skill and discipline, and the ruthless use of slave labor, would rectify the worst damage and restore lost production within months. The surviving dams could maintain a reduced water and power supply. If the Sorpe had also been breached, Speer said, “Ruhr production would have suffered the heaviest blow.”

Hitler ordered 27,000 workers and slave laborers to clean up the damage and repair the Möhne and Eder dams. Over Speer’s objections, 10,000 were diverted from building the Atlantic Wall defenses. At the postwar Nuremburg trials, he stated: “The transfer of these workers…into Germany amounted to a catastrophe to us on the Atlantic Wall.” Allied soldiers wading ashore at Normandy, encountering half-finished coastal defenses, were major beneficiaries of the raid.

The surviving “Dambusters” found themselves famous at home and in the U.S., where Winston Churchill was visiting President Franklin Roosevelt. Thirty-three medals were awarded, making No. 617 the most highly decorated squadron in Bomber Command. Guy Gibson received the Victoria Cross—one of only 23 awarded to the 125,000 RAF Bomber Command crewmen in the war—before leaving for a lecture tour in America. On his return he chafed to get back on operations. Reluctantly, the RAF acquiesced. On September 19, 1944, serving as master bomber for a raid on München Gladbach, he circled in his Mosquito above the target at low altitude, ignoring flak and directing the bombing before transmitting: “OK, chaps, that’s fine. Now beat it home.” Minutes later he crashed in Holland. The Dutch buried him there.

For the rest of World War II, 617 Squadron flew as a special operations, precision-bombing unit, dropping the heaviest conventional bombs of the war, Barnes Wallis’ 6-ton Tallboy and 10-ton Grand Slam. Today the squadron operates the Tornado GR4 fighter-bomber in the ground attack, anti-shipping and reconnaissance role. RAF Scampton is now home to the RAF’s aerobatic team, the Red Arrows. All subsequent commanding officers used Guy Gibson’s old office. From its window one can see a small grave, that of his Labrador. The station’s museum has photos of the dams, and one of Gibson’s caps. It’s just a 20-minute bus ride from Lincoln, whose great cathedral was a welcome sight to aircrews returning from Germany.

RAF Bomber Command veteran Nicholas O’Dell last wrote for Aviation History about jet engine developer Sir Frank Whittle. Further reading: The Dam Busters, by Paul Brickhill; Enemy Coast Ahead, by Wing Commander Guy Gibson; A Hell of a Bomb, by Stephen Flower; and The Men Who Breached the Dams, by Alan Cooper.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2013 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today

Need to build your own “Dambuster”? Click here!