It took no time for word of Clement L. Vallandigham’s astonishing “banishment” to the Confederacy in May 1863 to reach newspapers across the country. The coverage was understandably imbalanced, however, with Union-loyal editors and correspondents the predominant voices behind narratives detailing the peculiar fate of the country’s most famous, anti-administration Copperhead. Just two days after Vallandigham’s Abraham Lincoln-sanctioned exile, an article titled “Vallandigham Sent South,” appeared in the May 27, 1863, issue of The Pittsburgh Gazette. Even then, questions and debates surrounding the legality of Vallandigham’s arrest and subsequent expulsion swirled on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Was it lawful for the U.S. government to order one of its own citizens found guilty of treason by a military court extradited to the care of the government against which it was fighting?

In the 159 years since, Confederate perspectives about the incident and its aftermath have been rare. The earliest manuscript, Speeches, Arguments, Addresses, and Letters of Clement L. Vallandigham, was published in 1864, and notably did not even name the Confederate officer with whom Vallindigham primarily interacted during his three-week exile. More recent scholarship—Frank L. Klement’s Clement L. Vallandigham’s Exile in the Confederacy, May 25–June 17, 1863, for example—only cursorily investigated his Confederate reception, and even then, Klement cited merely two primary Southern sources: newspaper articles published in The Chattanooga Daily Rebel, in which the unnamed correspondent provided no account of the actual transfer on May 25, 1863.

Klement’s 1999 biography The Limits of Dissent: Clement L. Vallandigham and the Civil War used an additional postwar account by Confederate Stephen F. Nunnelee, yet information about the location and manner of the transfer seems misinterpreted when compared in light of other contemporary Southern documents. Meanwhile, in his 2020 book Opposing Lincoln: Clement L. Vallandigham, Presidential Power, and the Legal Battle Over Dissent in Wartime, historian Thomas Mackey briefly addresses Vallandigham’s banishment in his introduction, but he does not take advantage of additional Confederate sources to unpack this important chapter of the controversial Copperhead’s life.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

What follows is a needed examination of the thoughts and experiences of the gray-clad soldiers who reluctantly accepted and ushered Vallandigham into Dixie in the middle of the 1863 Tullahoma Campaign.

On May 25, 1863, Private Stephen Nunnelee of Company H, 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers, found himself in “neutral ground” between the Union and Confederate lines in Tennessee, sitting anxiously astride his horse. Intense skirmishes erupting on a daily basis and the growing likelihood of an all-out Union advance made Nunnelee’s job all the more dangerous. The bright rays of sunlight beat down upon him as he impatiently sat, unarmed and alone, on the Shelbyville Pike, just north of Old Fosterville, awaiting the unknown Yankee cargo entrusted to him for safe passage into Confederate lines.

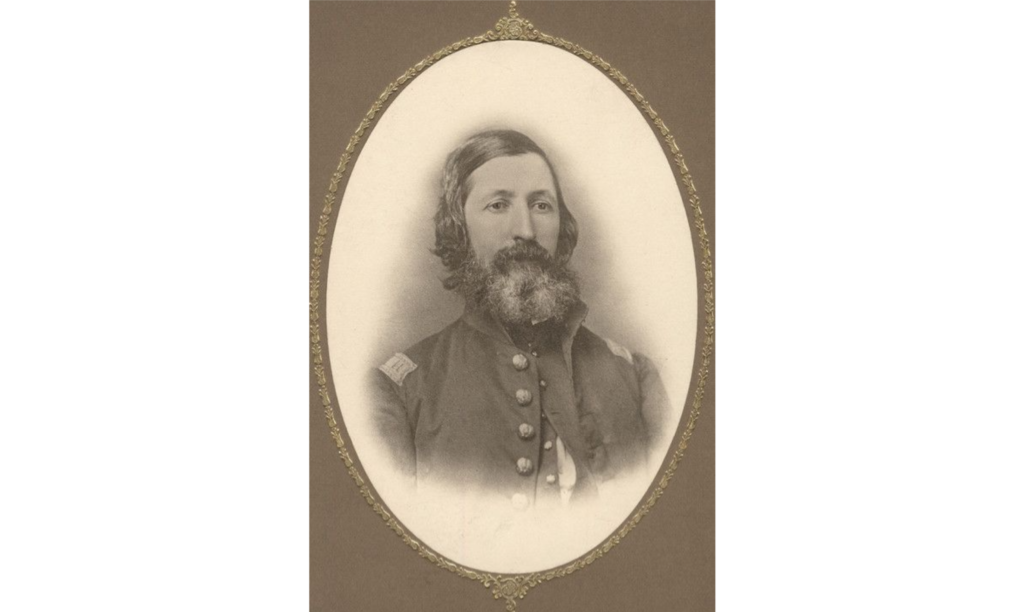

About dawn that day, 51st Alabama commander Lt. Col. James D. Webb received a dispatch addressed “to the officer comdng forces on Shelbyville Pike” that read: “Head Qrs Department of the Cumberland Murfreesboro Ten May 24 1863. Sir. By order of the President of the United States it is directed that the Hon C.L. Vallandingham [sic] shall be placed outside the lines of the Army of the Cumberland. A flag of truce will accompany him & he is consigned to your respectful attention. By order of Genrl Rosecrans – J.C. McKibbin Col & ADC.”

Mounting their horses, Webb and Captain Nelson D. Johnson of Company F rode three miles from regimental headquarters to the vedette post, where they found 1st Lt. William Fain of Company A, commanding the picket, seated upon a log and casually conversing with two U.S. officers: Colonel Joseph McKibbin (Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’ senior aide-de-camp) and Major William Wiles (the Army of the Cumberland’s provost marshal general). After formal introductions, Webb expressed astonishment that McKibbin had approached the Confederate lines with such an ostentatious intention, but if the Union colonel vouched for its truthfulness on assurance of his honor, he would accept their flag of truce. The officers assured Webb of the veracity of their orders, and also expressed expectation that the Confederate officer easily relent and allow their political prisoner to be ousted into Rebeldom without fuss.

A successful attorney and legislator before the war, Webb was not about to overlook the nuances of protocol in this tense tactical, operational, and increasingly political situation. He skeptically pointed out that the official letterhead read “Department of the Cumberland – Provost Marshal’s Office,” thus questioning the dispatch’s validity, as it appeared to come from the provost marshal and not directly from Rosecrans. The two men confessed they had requested the document be altered, which McKibbin had done in pencil. The hasty edits spurred Webb to dismiss their claims of sincerity and to threaten cutting off further communications, but the Federal officers reiterated that their orders came directly from Lincoln.

“[T]he President of the U States had not right to attempt to transfer to our lines any person with out our consent,” Webb succinctly reminded them. “[I]f you are charged with the safety of Mr Vallandingham [sic] keep him. surely you do not propose to transfer to your foe your responsibility. Keep Mr V & his baggage if you are responsible for him & for it.”

Webb was quick to point out that the Confederacy “owed no allegiance to the Constitution or the government of the United States…” and that it “did not now have or ever here after intended to have any conncexion [sic] with it or the people thereof except as a foreign power & nation of people.”

Although the Confederate commander vowed not to recognize Vallandigham’s existence in cooperating with the Union officers, if the Ohioan did appear outside Confederate lines and request permission to enter, Webb promised he would answer. With that, McKibbin and Wiles reiterated their determination to dump Vallandigham on the Confederacy’s doorstep. They requested that Webb provide a single escort to ensure Vallandigham and his baggage passed through the lines unmolested and, in turn, they promised the escort’s safe return. Webb acquiesced.

Lieutenant Fain selected Nunnelee as the escort. Although a relative newcomer to the mounted Alabama unit, Nunnelee had seen action during the Mexican War. Until 1861, he owned and published The Independent Observer, a pro-secession newspaper in Alabama. He also served as a lieutenant in the 11th Alabama Infantry early in the war. Most recently, he had, as a captain in the 4th Alabama Volunteer Militia, aided in the defense of Mobile.

“Colonel Webb sent for and ordered me to go to the outpost and escort a flag of truce between the lines,” Nunnelee recalled, “and to put on my best ‘bib-and-tucker.’ I changed my wool hat for a new, home-made gray jeans cap, or bonnet, which my wife had made, and proceeded, having a very indefinite idea as to the purpose of my mission.”

Not long after arriving at the vedette, he observed two men in a wagon thundering down the pike, “driving like Jehu.” Two Union officers pulled up under a large oak tree and Nunnelee advised them of his orders to protect their flag of truce. Turning their wagon around, the officers and Nunnelee sped down the pike at breakneck speed. At the same time, Webb sent Captain Johnson to the headquarters of Colonel James Hagan, his brigade commander, with verbal instructions to report what had transpired between him and the Union officers and to seek permission for Vallandigham’s admittance if requested.

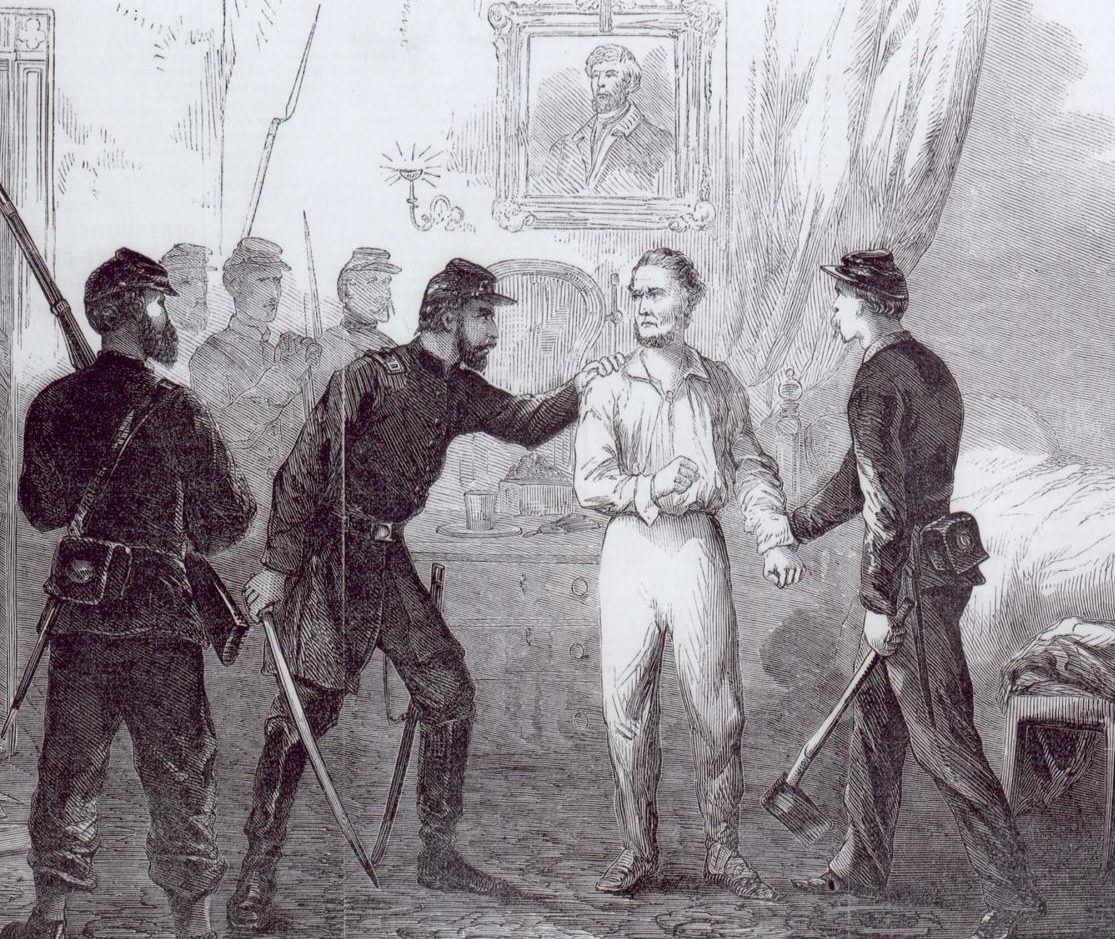

Upon reaching the outskirts of the Union lines, McKibbin asked Nunnelee to remain and await their return. “I was protecting his flag, which he bore away, leaving me without one,” Nunnelee recalled, “and I asked myself, ‘Who is protecting me?’ Of course, I had no arms and didn’t know the fellow who was posted a hundred yards ahead of me.” Thankfully, in less than 30 minutes he witnessed the flag’s return over the ridge and also noticed the wagon now had an additional passenger, Vallandigham.

Before disembarking from the wagon, the Ohioan stood erect and announced: “In the presence of this gentleman I protest against being forcibly taken from my State and my family.” Unsurprisingly, Vallandigham’s plea fell upon deaf ears. His escort, Wiles and a Captain Goodman, cooly remarked that they were merely obeying orders. Nunnelee assisted Vallandigham with his trunk and watched him hand several letters to one of the officers, requesting it be mailed to his family. Then, for a second time, Vallandigham protested his forced expulsion.

Nunnelee remains nameless in most Vallandigham biographies, portrayed simply as one of Webb’s orderlies who had no knowledge of the plans for dealing with the infamous political prisoner. The newspaperman-turned-soldier told a different story, however, relating that he stepped forward and offered Vallandigham his hand. Nunnelee noted to Vallandigham that he had sent him a copy of his Independent Observer while the Ohioan was in Congress. Vallandigham immediately remembered the Confederate printer’s name, and the two engaged in cordial conversation. Vallandigham queried Nunnelee, asking why he was in the Confederate Army, what position he held, and how many of “his sort” were in the army? The trooper retorted he was “playing soldier…trying to keep Rosecrans from running over us”; that he was “a high private in the front rank,”; and that “nearly all of us were there.”

“They can never whip you,” replied Vallandigham.

Nunnelee listened intently as Vallandigham provided an account of his arrest and all that had transpired up to his conviction and banishment. On May 24, the Copperhead recalled the he had boldly requested that Rosecrans assemble his men “in a hollow square tomorrow morning and announce to them that [he] desires to vindicate himself,” although Rosecrans had demurred. Vallandigham claimed that many of the general’s soldiers already opposed the war and would have mutinied. Rosecrans indicated, however, that he had denied the request because he “had too much regard for the life of the prisoner to try it.”

By the summer of 1863, many Union soldiers embraced emancipation’s necessity, as Lieutenant Orville T. Chamberlain of the 74th Indiana Infantry would write, “the labor of the copperheads” effectively “abolitionize[d]” the Army of the Cumberland and that even Democratic officers in his own company began sounding like “black hearted abolitionists.” Whatever the reason, Vallandigham did not receive permission to argue his case before the Army and presently found himself awaiting Webb at the home of Mr. [Jeremiah] Odell, a mere 600 yards beyond Confederate lines.

While awaiting Johnson’s return from brigade headquarters, Nunnelee arrived with news of Vallandigham’s appearance and of his request to speak to the officer in charge. Webb, then engaged in formally writing Hagan, paused the correspondence and rode out to see Vallandigham. After dismounting at Odell’s home, Webb approached the Copperhead, who then indicated he wished to surrender as a prisoner of war. After briefly questioning the Ohioan, Webb informed him that since he was a loyal citizen of the United States—a noncombatant, brought to the lines against his wishes, and not a spy—no charges could be levied against him by the Confederacy. He offered, however, that if Vallandigham wished “to enter our lines as a refuge[e] from this tyranny & oppression from which the government of the U States have forced you for the last two years, I will make known your wishes to the commander of my Brigade & ask his instruction & inform you.”

After their conversation, Webb returned to Confederate lines, completed his correspondence to Hagan, sent it via Nunnelee, and awaited further instructions. In the meantime, Johnson returned and passed along an order from Hagan not to admit Vallandigham until further notice. The captain advised that General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, had been telegraphed at his headquarters in Shelbyville. As soon as Brig. Gen. William T. Martin, Webb’s division commander, received an answer, it would be forwarded to the front.

According to Webb, the answer came about 1 p.m.: Vallandigham was ordered admitted to the Confederacy. Mounting his horse, Webb rode to Odell’s home and relayed the news. While there, he congratulated Vallandigham “on his escape from a land of tyranny & oppression & was proud to welcome him to the Confederate States, the land of Constitutional & religious liberty.”

With the news, the men rode safely through the vedette into Confederate lines. At the house of a Mr. Newman, Webb and the newly accepted exile met Martin, Hagan, and Captain Charles Force, commander of the 51st Alabama’s Company E (the company chosen as Vallandigham’s escort). The entourage mounted and continued their trek to Martin’s headquarters, where, shortly after 3 p.m., Vallandigham met Lt. Col. J. Stoddard Johnston, Bragg’s assistant adjutant general. Vallandigham’s transfer to Johnston would be the final time Webb would encounter the Copperhead.

Vallandigham was escorted by carriage to army headquarters. As a testament to his popularity among some Confederates, Johnston requested the Ohioan’s signature as “a memento of the event which has brought you among us—a banished Exile, forced from your home by despotic power.”

Within days, the entire incident made its way into countless newspapers, even landing a column in the obscure The Cecil Whig of Elkton, Md. The printed dispatch stated that upon arrival at the Confederate lines, Vallandigham told the Union officers charged with escorting him that “he was a loyal citizen of the United States.” It further reported that “he made the same remark to Colonel Webb of the 8th Alabama, to whom he was handed over” and continued by stating that “the Colonel told him he had read his speeches, but did not like him; he would however, permit him to remain at his post until the pleasure of the authorities should be known.”

One of these numerous printed accounts found its way to Webb’s headquarters in Old Fosterville. In response, he penned a letter to his wife, Justina, correcting the erroneously printed dispatch:

You will see it reported in some of the papers that Col Webb of the 8th Ala Regt told him Vallandingham [sic] that he had read his speeches & I do not like you. The number of my Regt is incorrectly given[;] it should be the 51st Ala Regt (PR). I told the officers McKibbin & Wiles I had read Vallandingham’s speeches. [H]e was no friend of ours. [H]e was a Union man. [A] reconstructionist. [W]e were opposed to that. [W]e did not like him as a representative of that principle. Mr. Vallandingham was not present at the interview with the Federal officers[;] he was then three miles off, at their picket line. He parted with me wishing me great happiness & again thanked me for my kindness & for the manner in which I had acted. I have given you this lengthy statement to place myself right. You know it is not for print or publication.”

Webb continued patrolling his key position along the Shelbyville Pike. Unknown at the time, the post was destined to bring him into contact with other significant individuals and events, such as “entertaining” Lt. Col. Arthur Fremantle, a British Army officer, during his personal sojourn through the Confederacy, as well as receiving the personal effects of the executed Confederate spies Colonel Lawrence W. Orton and Lieutenant Walter G. Peters, while under another flag of truce. Webb also managed to escape wounding or capture during the Confederate cavalry debacle at Shelbyville on June 27, 1863. (Nunnelee, it should be noted, was seriously wounded and subsequently captured in that engagement.)

Interestingly, Webb was not through entertaining questions about his well-known contact with Vallandigham. As the Battle of Gettysburg raged in Pennsylvania, the Army of Tennessee retreated across the Elk River outside Winchester, Tenn., where the 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers assisted in an effort to stymie a Union advance across the river at Morris’ Ferry. According to Private Enoch Morgan of Company I, Webb was “wounded on the evening of July 2nd in a heavy cavalry fight about 3 miles below the ford of the Elk River on the Winchester & McMinnville road. The ball struck him in the right side in front, passing through the lower part of the liver & lodged under the skin behind.” Unable to remove him from the field, several of his men, including Morgan, took him to a nearby house but were forced to abandon him to the pursuing Union cavalrymen.

That evening, Union Maj. Gen. David Stanley sent Jacob R. Weist, the 2nd Cavalry Brigade’s acting surgeon, to check on the feasibility of transporting the wounded Confederate officer into Union lines. The wound’s severity made moving Webb infeasible. Weist recalled, however, that “though the colonel knew that he was mortally wounded,” he seemed more than willing to converse on the subject of Vallandigham.

As Weist wrote:

“I made some inquiries about the great copperhead. Among other things the colonel told me was that VALLANDIGHAM TOLD HIM THAT THE SOUTH DID NOT PURSUE THE RIGHT POLICY; THAT INSTEAD OF ALLOWING THE NORTH TO INVADE KENTUCKY AND TENNESSEE…, THEY SHOULD TRANSFER THE BATTLE-FIELDS TO OHIO AND INDIANA…; that the Administration would be compelled to recognize the independence of the South.”

The particulars of the Webb–Weist interview cannot be corroborated with other contemporary eyewitness accounts. In his meticulously written June 9, 1863, letter to his wife, Webb did not mention any such policy. Therefore, Weist’s account could possibly have been strategically crafted to increase public disapproval of Vallandigham and his fellow extremist Peace Democrats.

Although an exact date cannot be confirmed, Webb likely died between July 4 and July 8. According to Weist, he died two or three days after being wounded. On July 8, Major Charles Seidel of the 3rd Ohio Cavalry concluded his official after-action report by stating that his “regiment, marching on the right, up the road, encountered the Fifty-first Alabama Cavalry” and “after a fight of ten minutes,” the Alabamians “fled in confusion, leaving his dead and wounded behind. Colonel Webb, commanding the Fifty-first Alabama, was severely wounded, and has since died.”

Fortunately, Vallandigham’s story of exile did not die with Webb in Middle Tennessee. Acceptance of the exiled Vallandigham into the Confederacy for those three weeks in the late spring of 1863 might seem trivial in comparison to the general upheaval and embarrassment caused by the Copperhead’s Mount Vernon speech, subsequent arrest, military trial, and banishment; however, the meeting between enemy contingents off the Shelbyville Pike on May 25, 1863, held potentially embarrassing political ramifications for the Confederacy and needed to be dealt with prudently. Webb exercised that prudence, and through his detailed and faithful correspondence to his wife, we can draw a more precise, holistic picture of this sensitive event when interspersed with other important narratives, such as those by Vallandigham and Nunnelee.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.