By Martin Gottlieb McFarland & Co., 2021, $39.95

There is ample reason why Clement Laird Vallandigham’s turbulent life story has rarely been chronicled. He was an unapologetic pro-slavery racist. He was an anti-war Northerner—some called him “chief of the Copperheads”—a bitter critic of the ultimately martyred Abraham Lincoln, and a failure in his own quest for high office in his native Ohio. At most a footnote figure, he is chiefly remembered as the target of an aggressive federal crackdown on free speech. No wonder his first—and, for generations, only—biographer was his own brother.

In fact, “Valiant Val,” as admirers dubbed him, has long cried out for a new look, and the task has been handsomely accomplished by Martin Gottlieb, retired columnist for the Daily News in Vallandigham’s onetime political base: Dayton.

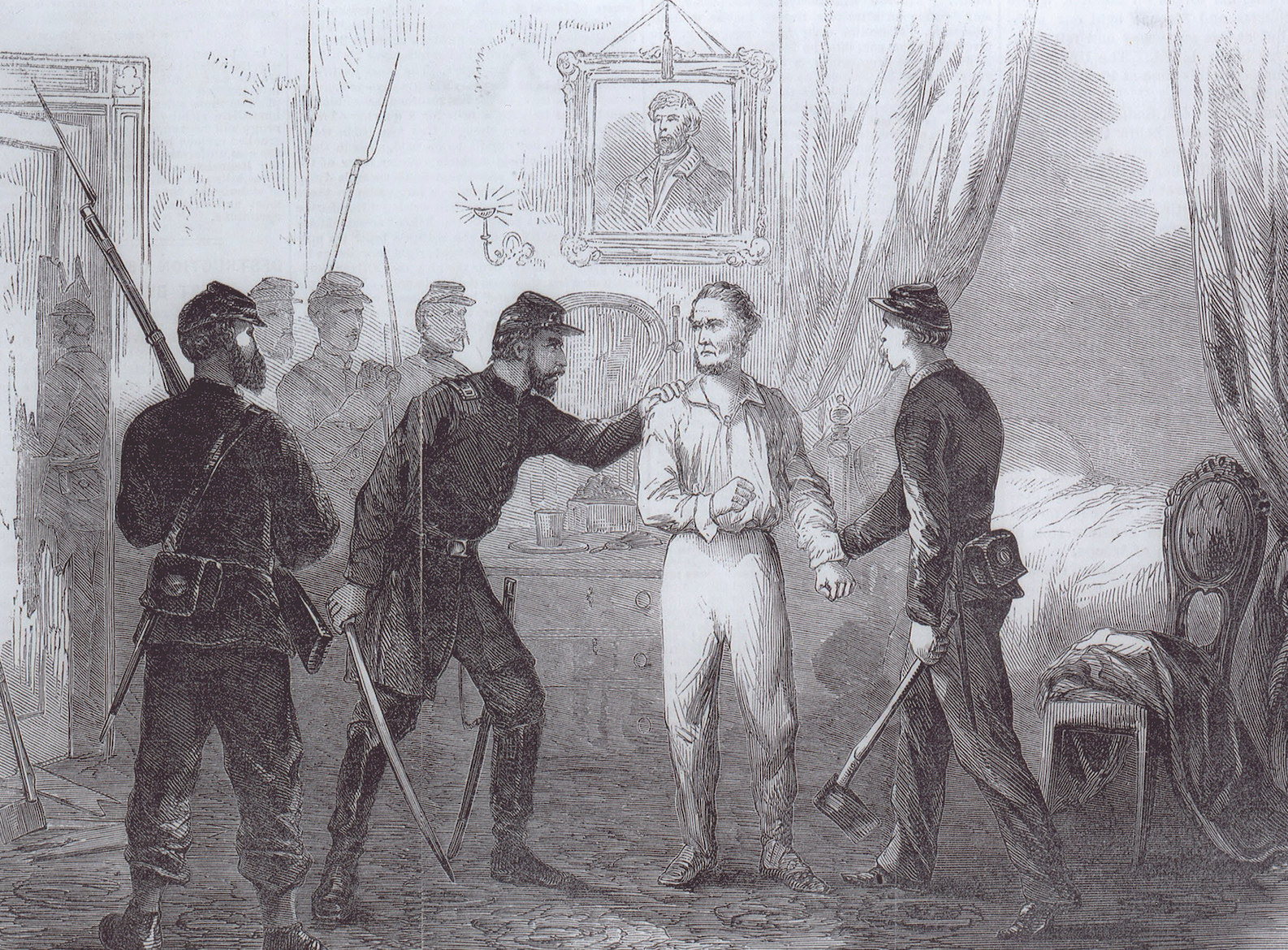

Born in 1820, Democrat Vallandigham became a state legislator at the age of 25—youngest in state history—and won a congressional seat in 1858. But he was ousted four years later, done in by his calls for peace, plus a bit of gerrymandering that titled his district Republican. Then Vallandigham won his greatest notoriety. After speaking out against the Draft in May 1863, he was arrested for “expressing treasonable sympathy.” Convicted by a military tribunal, he was sentenced to prison for the war’s duration. Lincoln (the man Vallandigham considered a despot) intervened and banished him to the Confederacy.

Escaping his exile, Vallandigham fled to Canada and from there ran for Ohio governor. When he was soundly defeated, a relieved Lincoln proclaimed, “Glory to God in the highest. Ohio has saved the nation.”

The ex-congressman managed a brief second act, not only attending the Democratic National Convention in 1864, but influencing adoption of a ruinous peace plank for the party platform. Lincoln’s re-election that November provided a resounding answer.

Gottlieb is a highly entertaining writer. I sometimes wished he had not been quite so informal in some passages, but he is a gripping story-teller and has done much research into period sources, particularly Ohio newspapers. The result is a fresh, nuanced, and illuminating portrait. Gottlieb reminded me that the Vallandigham case encouraged Edward Everett Hale to write Man Without a Country, now far more famous than its inspiration.

Had Vallandigham really “assumed racism in his audiences rather than fomented it,” as Gottlieb argues? I was more convinced by the author’s assessment of Vallandigham as a “slightly unhinged,” “long-winded” gadfly convinced that being “Republican Enemy No. 1” would earn him the legacy he coveted.

Indeed, Vallandigham might have achieved enduring renown as the most prominent victim of government censorship had he not poisoned his reputation with his racist rants. Ironically, Vallandigham died after accidentally shooting himself while demonstrating a plausible explanation for a legal client’s alleged crime. One might say he shot himself politically and historically, too, letting prejudice and Southern sympathy override his one claim to fame.

[hr]

*Thank you for visiting historynet.com. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.