During a marathon torture session, something extraordinary happened to Air Force 1st Lt. John L. Borling, a prisoner of war at the “Zoo,” a prison outside Hanoi. The pilot of an F-4 Phantom II fighter-bomber was “trussed up” with shackles, ropes and handcuffs that inflicted pain and could break bones. When his captors left him alone in the room, Borling managed to loosen the bindings and scooted over to a nearby desk, where he discovered letters in one of the drawers. While he rummaged through them, hoping to find one addressed to him, his captors burst in.

“I had a handful of envelopes, and they ripped them out of my hand,” Borling recalled, “and there was the ‘Man on the Moon’ stamp that absolutely riveted me.”

He was pummeled to the point of semiconsciousness. Back in his cell, Borling used a POW “tap code” to issue a news bulletin. “I tapped on the wall, ‘We own the moon,’ and I can remember how excited people were,” he said. “This was a tremendous morale boost. It contributed to staying power, and I can tell you for me it was uplifting. It’s still uplifting.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Borling reckons he saw that postage stamp in June 1970, nearly a year after astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked in the moon’s Sea of Tranquility on July 20, 1969. However, around the time of the landing, the POWs heard some tantalizing statements through the radio speakers that were common in the prisons. Radio Hanoi, which transmitted propaganda in English to U.S. troops (often through an announcer the Americans dubbed Hanoi Hannah), proclaimed: “No one has to go to the moon to see craters. All they have to do is look at the countryside of Vietnam;” “It doesn’t take Neil Armstrong looking from the face of the moon to tell that the U.S. is losing the war in Vietnam;” “You can send a man to the moon and back, but not bring your troops back from 10,000 miles away.” However, the prisoners never could be sure that Radio Hanoi’s pronouncements were true.

Navy Lt. Mike McGrath, who flew from the carrier USS Constellation in an A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft before being captured, was in the Zoo when rumors about Apollo 11 began to circulate, around late 1969, he thinks. “Someone got a package, and there was a sugar packet with a picture of Neil Armstrong standing on the moon with the flag,” McGrath said. “We had a unilateral bombing halt [beginning in November 1968] and no POWs [newly downed and captured aviators] came in with news for four years.” The discovery of the sugar packet picture “was one of the brightest days.”

NO Satellite, No live coverage

NASA estimates that 530 million people worldwide watched the live broadcast of the moon landing 250,000 miles away and heard Armstrong’s historic words, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind,” at 10:56 p.m. Eastern U.S. time on July 20 (10:56 a.m., July 21, Vietnam time).

The approximately 500,000 U.S. service members in Vietnam were among the few Americans who couldn’t watch the event as it happened. With no satellite service over Vietnam, a live broadcast was technically impossible. Troops with access to a television saw delayed coverage through American Forces Vietnam Network, a Saigon-based radio and TV broadcasting service with eight stations across South Vietnam.

Recommended for you

FLying in Film

The AFVN brass had arranged for recordings to be flown in from Hawaii on the day of the moon landing, and Army Sgt. 1st Class Bob MacArthur was waiting to anchor the show in the Saigon studios.

“The Air Force was supposed to shuttle new film in every two hours,” according to radio announcer Army Spc. 5 Larry Green, “but there were delays, so Bob had to ad lib for hours.”

The first recordings arrived three hours after the AFVN coverage was scheduled to begin, according to MacArthur’s biography at the website macoi.net. “He discussed the history of aviation and the space program for the entire time without notes and with no teleprompter. He was noticeably hoarse when the tapes finally arrived.”

Subsequent recordings were flown in from the Philippines and broadcast in Saigon about five hours later.

Copies of the tapes were made in Saigon and shipped to upcountry stations, which meant additional delays of hours or more. In the northern part of South Vietnam, the Quang Tri station aired the films one day after the Saigon broadcast.

Watching History in a Hut

Among those who watched AFVN’s delayed coverage was Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class Harry Hahn, a radioman assigned to a howitzer-equipped river boat at Go Dau Ha, near the Cambodian border.

“I wandered into a little hut, and there was a black and white portable TV sitting on a chair,” he said. “We adjusted the rabbit ears, and another sailor and I watched the moon landing together. It was a moment I will never forget as a proud American serving in a war!”

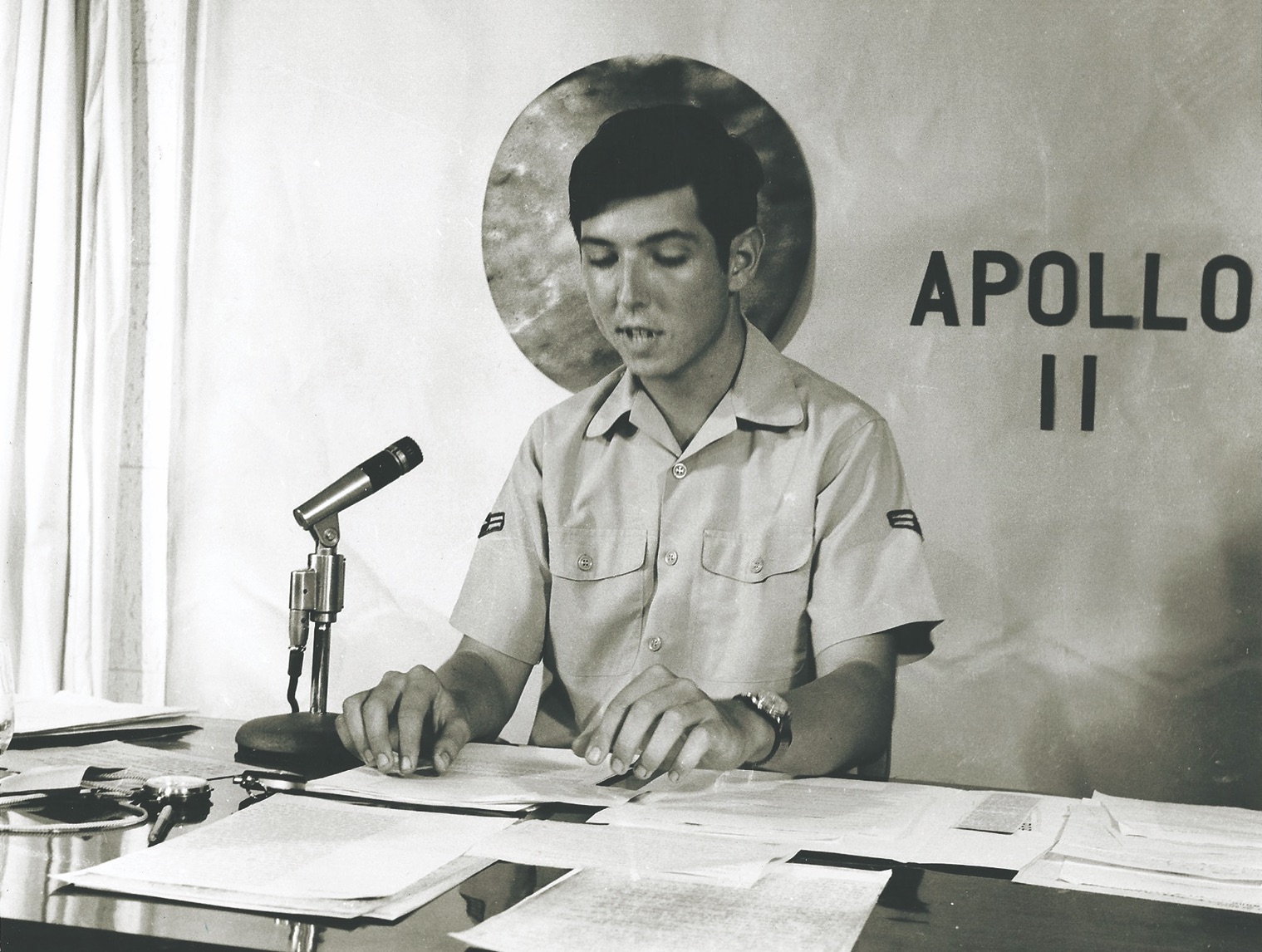

The station at Tuy Hoa, on the coast in central South Vietnam, devised a novel alternative. AFVN’s radio operations were able to provide live reporting from civilian networks, thanks to an undersea audio cable from the States, so the Tuy Hoa station broadcast the radio feed over its TV channel, with Airman 1st Class Bob Young anchoring the coverage on-camera with generic space video or slides.

When the visual recordings finally arrived, Young remembers, “The images were not that great, and it was difficult to make out what we were seeing.” Despite the poor quality, he drove a copy to a military unit whose TV reception was blocked by a mountain and gave troops a private showing on a projector in their chow hall.

President to President

The day of the moon landing, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu issued a congratulatory statement to President Richard Nixon. It said, in part, “We wholeheartedly concur in the message of peace, which the brave astronauts carry for mankind to this new frontier of human beings.”

On July 30, Nixon traveled to South Vietnam to meet with Thieu and visit with soldiers of the 1st Infantry Division at Di An, about 10 miles northeast of Saigon. Nixon’s trip was code-named “Moonglow” to commemorate the astronauts’ achievement.

In the POW Camps

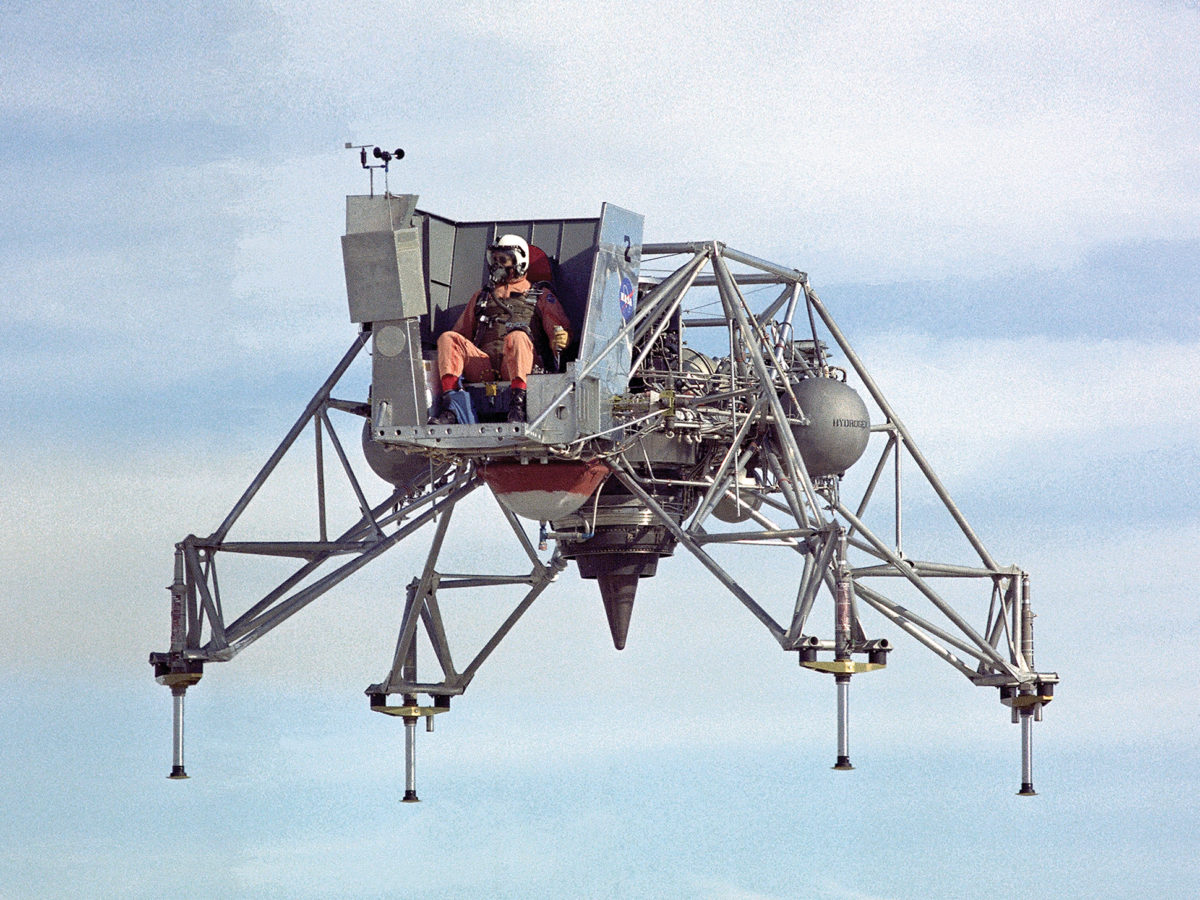

Many of the Americans suffering in North Vietnam prisons had a common bond with NASA’s spacemen: They were aviators. Navy pilot Lt. j.g. Charlie Plumb had even taken his physical hoping to become an astronaut, but his F-4 was shot down by a missile south of Hanoi in May 1967 and he joined other American POWs at the Zoo.

Plumb says the POWs “were probably the last people on Earth to find out we put a man on the moon,” but eventually, like other prisoners, he was able to piece together the news.

Guards passed propaganda newspaper stories under his cell door, and one article from the Soviet news agency Tass seemingly bragged about another victory in space. Plumb paraphrased the key sentence: “We [Soviets] have sent a vehicle to the moon to gather samples, taken pictures, blasted off and returned safely to Earth and, unlike the Americans we didn’t have to put a man aboard to control the vehicle.”

“I read that a couple times,” Plumb said, “Then I tapped the thing word-for-word to the guys in the cell next door. They interpreted it the same as I had, that, in fact, we had put a man on the moon.” The POWs were jubilant. As Plumb described their excitement: “Holy smokes, we put a man up there. We knew it had to be one of our fellow pilots. It helped us hang on.”

AT Di An

Army Sgt. Dennis Morrison, with the 1st Signal Brigade at Di An, had to work a 12-hour shift during the moon landing and thus couldn’t listen to AFVN’s radio coverage. So he taped it using a reel-to-reel recorder in his hooch. Morrison started the recorder and let it run while he was at work. He still has the news wrapup anchored by Army Spc. Mike Maxwell. “I play the CD all the time in my truck,” Morrison said. “My wife got tired of hearing it.”

Morrison’s obsession is justified. He and Armstrong were both born in Wapakoneta, Ohio, a small town now home to the Armstrong Air & Space Museum. Morrison gave the museum a copy of his recording so visitors could experience the Apollo 11 coverage the same way the troops in Vietnam did.

Rick Fredericksen was a Marine newsman at American Forces Vietnam Network in 1969-70. He is the author of e-book “Broadcasters: Untold Chaos.”

This article appeared in the August 2019 issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.