The Navy Fighter Weapons School, an advanced training program better known as Topgun, dramatically increased the shootdowns by Navy aviators during the Vietnam War.

U.S. pilots flying missions over North Vietnam faced dangers from anti-aircraft guns, surface-to-air missiles and enemy pilots in Soviet- or Chinese-made MiG fighters. Weapons malfunctions were also a constant fear. When U.S. Navy and Air Force pilots first entered Vietnam combat in March 1965—following stellar performances in World War II and Korea—they ventured forth with a certain cockiness. But American aircrews took unexpectedly serious hits from North Vietnamese pilots who studied U.S. tactics and learned to counter them. Directed by ground radar, enemy pilots launched effective hit-and-run slashing attacks on large U.S. aircraft formations and became even bigger threats with Soviet training and improved MiGs.

Navy pilots “had gone into the war thinking we were the best pilots in the world flying the best aircraft armed with the best weapons,” writes Dan Pedersen in “Topgun: An American Story“. “The North Vietnamese showed us otherwise. We were ready to do whatever it took to win.”

From February to July 1968, Pedersen flew missions in an F-4 Phantom II fighter-bomber catapulted from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, off the coast of North Vietnam. He was then assigned to a Phantom squadron at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego, where he was put in charge of the group that created the Topgun training program.

INauspicious Start

I parked my sea bag at Miramar in the fall of 1968 to serve as a tactics instructor at Fighter Squadron 121, the fleet replacement squadron for all F-4 Phantom squadrons based on the West Coast. Anytime a carrier in the Pacific lost a Phantom, V-121 produced a replacement plane and a two-man crew. Our fighter squadron was the largest in the Navy when I was there. It had an average of about 70 F-4Bs and F-4Js assigned to it, and 1,400 officers and enlisted men. A training command, it made sure the squadrons that operated from our carriers were at full strength and ready to go.

I was an instructor in the advanced tactics phase (or department) of the squadron. Lt. Cmdr. Sam Leeds was head of tactics. Basic air combat tactics was my area. The syllabus was standard Navy tactical doctrine, complying with all the published guidelines about how the F-4 Phantom should be flown. Our students learned how to fire their weapons, drop bombs and use long-range radar to intercept a distant target. It was about as advanced as biology for English majors.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

A new Way to Train

Late in December, Leeds showed me a thick document bound in a blue cover. It was a study issued by the Naval Air Systems Command and titled, “Report of the Air-to-Air Missile System Capability Review.” This study, produced by Capt. Frank Ault, the captain of aircraft carrier Coral Sea, was an impressive, consequential piece of work.

About 200 pages long, it was a top-to-bottom exploration of the reasons for our failure in air-to-air combat over North Vietnam. Ault’s project began in the summer of 1968, when he led a team that tackled the problem of the radar-guided Sparrow air-to-air missile, which usually malfunctioned or missed. He pulled in more than 200 people for a symposium at the Naval Air Missile Test Center at Point Mugu, north of Los Angeles. There were pilots, commanders, and managers and technicians from Raytheon, Westinghouse and McDonnell Douglas, all the major fighter weapons contractors. It was the first time the whole air combat system had been studied from design and acquisition to operations and logistics.

Leeds called my attention to one particular recommendation in the report. He flipped to page 37 and pointed to the 11th of the 15 items listed in paragraph 6, “Aircrew Training.” It was there that Ault advised the chief of naval operations and the commander of Naval Air Forces, Pacific, to “establish, as early as possible, an Advanced Fighter Weapons School” at Miramar for the F-8 Crusader and F-4 Phantom. Those were the words that gave birth to Topgun.

Leeds and I knew that any Miramar-based tactics training program would run through us. He looked at me and said, “Dan, why don’t you take it?”

He had experience and seniority over me. He could have led the effort himself. But he was in the final running to command the first fighter squadron that would fly the F-14 Tomcat (which Tom Cruise would help make famous in his 1986 movie Top Gun). I made a quick, fateful decision: I’d do it.

When we informed our skipper, Cmdr. Hank Halleland, that I had agreed to serve as the Navy Fighter Weapons School’s first officer in charge, he had only one directive: “Don’t kill anybody, and don’t lose an airplane.”

He also made it clear that we would have no classroom space, ready room or administrative office, no maintainers and mechanics assigned to us, no airplanes of our own, only loaners. And, of course, we would have no money. The new graduate school would subsist by forage, hunting and gathering in the forgotten corners of Miramar. Our deadline for preparing a curriculum and having it ready for the first class was short: 60 days. Aside from all that, I suppose the job was a real plum.

TOPGUN is born

Soon we started calling the school Topgun. We weren’t the first to use this fine nickname. There was an annual air weapons competition that used it until about 1958. The aircraft carrier Ranger, which I would later command, called itself “the Top Gun of the Pacific Fleet.” Our friends and rivals at Miramar who flew the older F-8 Crusader called themselves “the last of the gunfighters.”

I’ve often reflected on the sheer happenstance of how leadership of Topgun fell to me. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was larger and more important than anything I had ever undertaken. It was the chance of a lifetime to effect much-needed change. Its success would require the work of the many fine aviators who followed me. But our graduate school in fighter combat would grow roots and flourish. It would transcend its own mission and stand for excellence and commitment of the purest kind. None of that was expected in December 1968. It was a job to do.

Designed to fail

The program almost seemed designed to fail. I say that because the Navy considers nothing very important that’s not run by an admiral. I was a 33-year-old lieutenant commander, three pay grades below admiral. That the Navy gave leadership of Topgun to someone so lowly speaks to what it thought of our chances. Most real tactical aviation training took place out in the fleet. The skippers of the fleet squadrons thought they owned tactics. Topgun threatened that approach. Thus, we could easily fail.

If Topgun crashed and burned, the senior officers standing over us would suffer no blemish on their records. Our failure could be written off to the stumbling of youngsters who, while well intended, were not up to the task. That’s probably why a guy like me got to be the first officer in charge.

I took comfort in Halleland’s support. He helped us find people and resources. The pedigree of the Ault report helped too. The higher echelons at Naval Air Forces, Pacific and the Pentagon had to pay attention, since the chief of naval operations had endorsed the study.

When I look back at how we pulled it together, it’s clear that the acting hand was far mightier than my own. I prayed for the gift of discernment to make it work.

Ault prescribed the creation of the Navy Fighter Weapons School but did not say what it should teach, how it should be taught or how it should be set up. Today, an initiative like that would involve millions spent on special studies and outside experts. The paper pushing would take years. In 1969, I was left to my own devices.

Hottest sticks in the sky

Our job was not just to teach pilots to be the hottest sticks in the sky. It was to teach pilots to teach other pilots to be the hottest sticks in the sky. Our first class of students, handpicked by their squadron commanders, would spend about five weeks with us and then return to their units to spread to their peers what we had taught them.

My first task was to find instructors with a talent for delivering a complex lesson. Around the time Leeds showed me the Ault report, I hosted a group of Israeli pilots at my home in San Diego. Heading the group was Lt. Col. Eitan Ben Eliyahu. He had a superb reputation as a fighter pilot and leader. When I met these guys, the IAF was making the transition from the French-built Dassault Mirage to the Phantom. They were visiting Miramar to learn what they could.

Over good American barbecue I discerned that Israeli fighter squadrons believed strongly in the power of technical specialization. In each technical area, Eliyahu explained, one man was designated the lead specialist. Radar, weapons, ordnance, aerodynamics, tactics—each domain had its wizard. That division of labor would be an efficient way to assemble a team of instructors and develop a technical curriculum on a short schedule.

I decided that eight men would be the right number to cover the subjects we needed to master. Four pilots and four radar intercept officers (back-seaters operating the radar, electronics, navigation and weapons systems) would join me as Topgun’s founding instructors.

The Best Pilots

I didn’t have to look far for good people. The pool of combat-seasoned talent at the F-4 replacement squadron was deep, which was helpful because there was no time to do the paperwork to transfer people from other units. The instructors who had been teaching with me flew every day, putting new pilots through the paces. Their reputations among the student pilots at Miramar were as important to me as their standing as warriors.

When the time came to choose my “original eight,”—the “original bros”—the right names came quickly to mind. I talked to each of them, had them read the Ault report and described the enormous task we faced in building a graduate-level program and preparing to teach it within 60 days for our hot start in March.

The pilots I invited to join Topgun as instructors were Lts. Mel Holmes, John Nash, Jim Ruliffson and Lt. j.g. Jerry Sawatzky. They did not hesitate to sign on. We had long been vocal about the changes we thought were needed to win the air war in Vietnam. Here was the chance to do something about it.

Recommended for you

Mel Holmes was a first-round pick in anybody’s book. I considered him the best F-4 Phantom pilot in the world in early 1969. He was a natural leader with strong opinions. One time when Holmes was golfing at the base course, he hit a drive into the weeds. That was bad news for the nest of rattlesnakes he walked into while looking for his ball. When his buddies saw him hacking away with his 7-iron, slaughtering those serpents in the grass, he had his nickname: “Rattler.” When Holmes strapped himself into the cockpit of a fighter, whatever separated the flight surfaces from the man at the controls simply disappeared. No pilot I ever knew beat Holmes consistently one-on-one. He was a perfect candidate to specialize in tactics and aerodynamic.

I chose John “Smash” Nash for the way his heart and mind worked together. I knew him from our early days flying McDonnell F3H Demons from the Hancock in 1963. Nash was at his best when pitted against a supposedly superior fighter pilot. But what made Nash special was the way he combined his competitive fire with hyperattention to detail. His talent for technical research kept our ideas about tactics on a deep base of fact. He told his students: “Automobiles, aircraft and air-to-air missiles are built to fail. Expect problems and anticipate them.” I considered his detail-driven aggression to be the best possible mindset for a Topgun instructor.

Jim Ruliffson probably put out more pure intellectual wattage than any of us. No one understood the Phantom’s electronic and avionics systems better than he did. With his superb technical mind and training in electrical engineering, Ruliffson was a natural to spearhead our effort to master the Sidewinder and Sparrow missiles. In the subtle differences in performance between these high-tech weapons, not to mention the optimal parameters of their use, was the critical margin between life and death. “Cobra” Ruliffson distinguished himself with his superb gift for teaching this complex material to aircrews.

Jerry Sawatzky, or “Ski Bird” as I called him, had played linebacker for Bear Bryant at Alabama. He was big, imposing and highly energetic, but also unassuming and one of the most likable people I ever flew with. Sawatzky had great situational awareness, vital in fighter combat. A pilot has to stay alert to what’s happening in the cube of air that extends several miles around him as all the players move at high speed in different directions. Sawatzky could teach others how to develop their awareness. He was also good at seeing an aerial encounter from the enemy’s point of view.

The Best back-seaters

Without a good back-seater in his F-4, no fighter pilot gets far in an air battle. Topgun’s four founding radar intercept officers were the best RIOs anywhere.

At the head of the pack was John “J.C.” Smith. He might have been the best RIO there ever was. In June 1965, flying from USS Midway, J.C. and his pilot, Cmdr. Lou Page, scored the Navy’s first air-to-air kill of the Vietnam War. The head-on tangle with a pair of MiG-17s was a by-the-book radar intercept, and the Sparrow performed as advertised. J.C. was especially good with new pilots. Whenever one needed help, I’d prescribe a few flights with J.C. in his rear seat. That always got him up to speed.

Another RIO was Jim “Hawkeye” Laing. During one of two combat tours in Vietnam, flying from USS Kitty Hawk, he and his pilot flamed a MiG-17 in a wild fight near Haiphong Harbor in North Vietnam. Laing survived two ejections in barely a month. In the second one, he and his pilot, Denny Wisely, landed in a thick jungle. As a helo looked for them, Nash remained overhead, covering the rescue to the limit of his fuel while under enemy fire. He received a Silver Star. Laing, with his history of survival against the odds, gave Topgun an element of moral strength and never-quit resilience that was enormously valuable. He was a generalist who contributed to each area of the curriculum.

A second Smith—Steve—was a top-grade RIO but stood apart for his skills as a salesman. Steve-O could talk a Bedouin out of his camel, ride it to Alaska with a load of shaved ice, and sell it all at a premium to an Eskimo. He also was a world-class organizer. He kept a daily to-do list in his pocket, and it was a rare sunset when he hadn’t scratched off every item. “Rebel” was at his best when I gave him free rein and didn’t ask too many questions.

RIO Darrell Gary was the youngest man in our cadre. He was mature (beyond his years), confident and hardworking. In cadet training, while everybody else was asleep, Gary would often be found sequestered in the head, sitting with a flashlight in one hand and a textbook in the other. He graduated at the top of his class in naval flight officer school. He had two combat tours on the Kitty Hawk. It was hard to miss his extreme self-assurance. Because evolution tells us that birds with that trait tend to become extinct, we gave Gary a call sign to match: “Condor.” It was designed to encourage him toward humility. But he was one of Topgun’s sharpest lecturers, gifted with a probing tactical mind.

Our last find was a nonaviator. Chuck Hildebrand was working as an intelligence officer, bored and unhappy, in one of Miramar’s F-8 photoreconnaissance squadrons, when Steve Smith met him. Smith recognized Hildebrand’s useful talent and helped arrange his transfer—all on the same day. Hildebrand got the inevitable nickname “Spook.” He never stopped collecting documents for our reference library, detailing the capabilities of enemy aircraft and pilots. Without Spook, Topgun would have needed many more years to emerge as a research library for fighter pilots and a center of knowledge that it quickly became.

Finding a home

With the team assembled, we needed a place to call home.

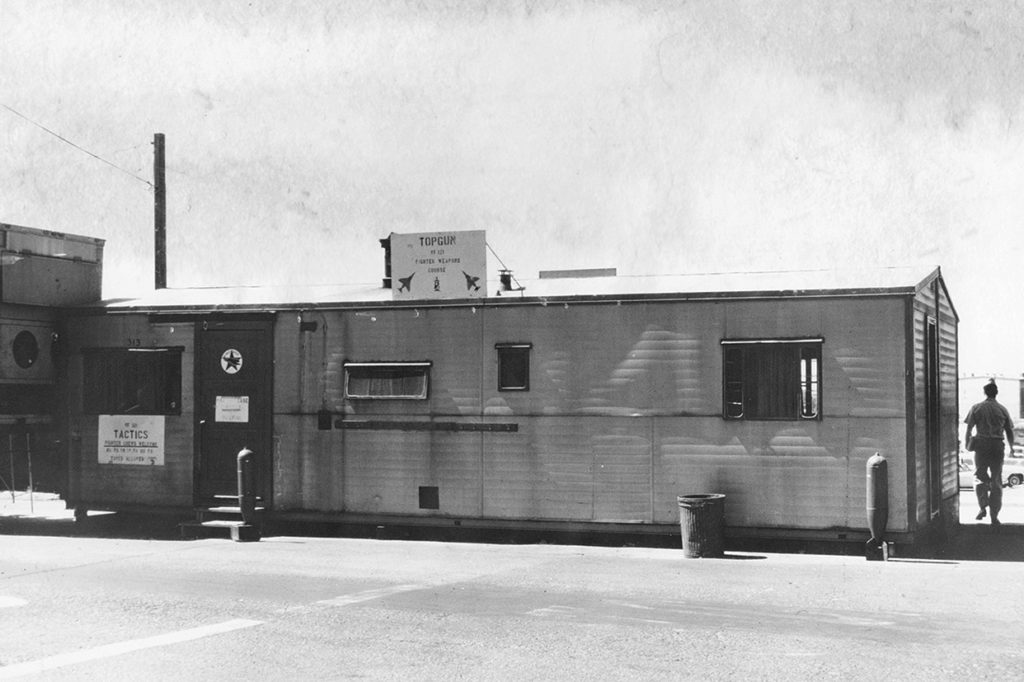

One Friday afternoon, Steve Smith, foraging in a remote part of the base, found an abandoned, dilapidated trailer. It was perfect. He chatted up an off-duty public works crane operator and offered him a case of scotch if he would make delivery to our area. Later that afternoon, the 10- by 40-foot structure was hoisted aloft and relocated to a space adjacent to VF-121’s hangar.

Over the weekend, we laid new flooring, repainted the trailer with bright red trim and hung a sign on the door announcing the existence of the Navy Fighter Weapons School.

Meanwhile, Smith went scrounging and stole a bunch of office furniture and a couple of classified-document safes from God knows where. Legend had it he bagged some of it from the Air Force. We filled our formerly condemned trailer with all the trappings of a real classroom and called it home. By Monday morning, Topgun was officially in business.

On March 3, 1969, in our stolen trailer, Topgun’s Class One convened. All eight attendees had come from Pacific-based squadrons, VF-142 and VF-143, just off a Vietnam deployment with USS Constellation. They were some of the finest junior officers in the fleet, all combat-experienced aviators, all graduates of the Naval Academy, career Navy. The pilots were Jerry Beaulier, Ron Stoops, Cliff Martin and John Padgett. The RIOs were Jim Nelson, Jack Hawver, Bob Cloyes and Ed Scudder.

Just the beginning

I issued a heartfelt “Welcome aboard” and said we had been charged with an important purpose. I introduced my instructor team. I explained that we would learn together along the way.

The main thing for any skipper to bear in mind is this: The troops need to know he’s interested in their welfare. This is true regardless of the leader’s communication style. Hard-asses can care too. Some leaders give lip service to caring, but what a leader does to show it is far more important. I wanted my instructors to challenge them—but always constructively. We would aspire to build their confidence, not destroy it. They were professionals and future mentors in training. So we were going to show them how it was done.

This article appeared in the August 2019 issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.