“Pull up! Fly the dot. Push over, go down!” U.S. Navy fighter pilot Dave Batson was aggressively working the flight controls of his F-4B Phantom in response to direction from his radar intercept officer Rob Doremus to optimize their position to launch an AIM-7 Sparrow missile, based on the steering cues on his radar scope.

It was around 10:30 a.m. on June 17, 1965, and they were “feet dry” (over land) about 40 miles south of Hanoi. Their Phantom was doing more than 500 knots, having flown an intercept of more than 30 nautical miles, and now, in close, things were happening fast.

On the radio Batson’s flight lead suddenly called, “It’s MiGs!”

Batson was ready. The pilot squeezed the trigger, and for the first time in his life a missile roared off his fighter.

Jack David Batson grew up in Buffalo, N.Y., and set his sights on flying. Inspired by a Navy ROTC instructor, he was soon hooked and longed to fly the Navy jets he saw at airshows and in magazines.

Batson graduated from Brown University in 1961 and was commissioned as an ensign through NROTC, entering Navy flight training on July 3. He earned his wings of gold in September 1962 and reported to Fighter Squadron 121 (VF-121), the Navy’s West Coast training squadron for the new McDonnell F-4 Phantom II, in October.

Batson said the first time he saw a Phantom it was “an out-of-body experience. Oh my God, it was huge!” But he soon gained confidence in his mount and completed training, reporting to his operational squadron, the “Freelancers” of VF-21, in June 1963.

While training at VF-121, Batson was paired with backseater Lieutenant Rob Doremus. At that time, radar intercept officers (RIOs) were members of the naval aviation observer community, the current designation—naval flight officer—being introduced in 1966. Doremus already had valuable aviation experience, having flown in Lockheed EC-121 Super Constellations and Grumman S-2 Trackers before joining the fast-mover club. (The post-1962 aircraft designations are used here for simplicity.) Batson and Doremus turned out to be a good match: The pilot said he still talks to his former RIO every week, 55 years after their aerial showdown.

Recommended for you

As for the Phantom, it was nothing less than a sensation when introduced, setting world records for speed and climb rate. It bested several capable challengers to emerge as a mainstay fighter and attack aircraft for the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force, as well as many allied nations.

Along the way, the F-4 lost its gun. Navy leaders had been seduced by the promise of “pushbutton combat,” with missiles scoring kills and eliminating the need for close-in maneuvering. It was no surprise that F-4 training squadrons emphasized radar intercepts at the expense of dogfighting. The syllabus was already crowded and many early pilots came from the McDonnell F-3 Demon, which lacked both power and agility. There were bright spots—pilots and RIOs who recognized the Phantom’s versatility and practiced dogfighting—but they were in the minority.

Lieutenant (j.g.) Batson was part of VF-21’s first deployment with the F-4, aboard the aircraft carrier Midway, departing Naval Air Station Alameda on November 8, 1963. A few days after leaving California they visited Hawaii and then spent the next 5½ months pinballing around the western Pacific, returning to Alameda in May 1964.

Preparation for the next deployment began in July. Batson and Doremus continued to fly together, honing their crew coordination while building flight time and experience in the sophisticated jet.

Batson described the training as “a lot of intercepts in Whiskey 291 [warning area W-291, a training airspace off San Diego] and some air-to-ground. Of course we also refreshed carrier quals.” But he added: “Things changed after August 2, 1964. Training became more intense. The air wing even practiced alpha strikes [large, coordinated attacks by the entire wing].” The date, of course, refers to the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which precipitated America’s official engagement in the Vietnam War.

Midway’s crew knew they were sailing for a combat zone as they left San Francisco Bay on March 6, 1965. The ground war was already hot, and the air war had entered a new phase when Operation Rolling Thunder began on March 2. Air strikes shifted from ad hoc events to a sustained campaign.

Crossing the Pacific, the aviators on Midway increased their combat preparations. One event that stands out in Batson’s mind was the briefing on rules of engagement (ROE). “I don’t think anyone except two Korean War veteran pilots had even heard the term,” he said. “When we got the brief we were aghast. Rule number one was you could not shoot somebody unless he displayed hostile intent. Rule number two was that you had to have visual identification [VID].”

These two requirements, while prudent in light of multiservice air operations and the command-and-control situation, nullified several of the Phantom’s strengths. Batson recalled that one of the F-4 crewmen remarked, “Well, there’s two years of training down the drain.”

Faced with this reality, VF-21 aircrews spent time thinking about tactics during the long Pacific transit. Among them were Commander Lou Page, the squadron executive officer and one of the more experienced pilots, and his RIO Lieutenant J.C. Smith. Smith was a former pilot who had switched seats and excelled as an RIO. Page and Smith put a lot of thought into the ROE and the requirement for a VID. Planning for a forward-quarter intercept (head-on approach), they decided the aircraft with the first radar contact would become the tactical lead, and the wingman would slide into a three-to four-mile trail. At the merge, the lead would visually identify the target and “disengage in the vertical” using the Phantom’s powerful thrust while the wingman launched a radar-guided Sparrow.

When Page and Smith briefed Batson and Doremus on the plan, all four aviators were concerned about the VID range for the diminutive MiGs. But they were not concerned that the wingman’s Sparrow would target his leader because their radar tracked Doppler, or closure speed, and only the approaching targets would be closing. Batson said the Sparrow was their “primary missile because the AIM-9B Sidewinder could only track a target in a 3G turn and had to be fired from a limited cone around the target’s tail.”

They discussed the plan and all agreed it was their best option, but they never had a chance to practice it.

Though Rolling Thunder was new, the war had been gaining intensity in the eight months since the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. Naval aviation had been bloodied, with dozens of aircraft damaged or destroyed in combat and several aircrews lost or taken prisoner. Carrier Air Wing 2 on Midway suffered its share of losses. There had been a few air-to-air engagements, revealing unforeseen weaknesses in the missiles, to the aircrews’ consternation. They were, after all, flying the sophisticated and expensive F-4.

Things were about to change.

On May 19 Midway sailed from the Philippines and was soon on Yankee Station for the second line period of the deployment. Air Wing 2 squadrons resumed their strike, reconnaissance and combat air patrols.

The 26-year-old Batson found himself flying combat missions about once a day. He was usually tasked with a MiGCAP: combat air patrol to defend strike aircraft from MiGs. Over the coast the naval aviators were not yet threatened by surface-to-air missiles, though they faced dangerous anti-aircraft artillery. Batson also stood alerts, ready to respond in the event MiGs tried to attack the ships on Yankee Station. Whether airborne or on alert, Rob Doremus was in his backseat almost every time.

June 17 started out as just another Thursday morning. Aboard Midway aircrews briefed for an alpha strike on the Thanh Hoa Bridge and nearby targets. Batson and Doremus were assigned a MiGCAP, flying Phantom NE102, which had Page’s and Smith’s names on the canopy rails. Their flight lead would be Page and Smith in NE101, which bore the names of VF-21 commanding officer Commander Bill Franke and his RIO, Lt. (j.g.) James Mills. The strike launched at 9 a.m. and refueled from a Douglas KA-3B tanker. The two Phantoms pressed north to establish their station. Four more F-4s also flew as MiGCAP.

Batson recalled that they orbited at an altitude of 10,000 feet “to provide look-up for the radar” and airspeed of 300 knots “for fuel considerations.” While they patrolled, the RIOs saw bandits on their radars, 50 nautical miles away over Hanoi—not a factor. The entire strike group was on a single radio frequency but the radio was relatively quiet, mostly calls from the Douglas A-4 pilots doing the bombing. Batson had been on 30 combat missions by then, and this one was going smoothly. The strikers completed their mission and called “feet wet” as they headed back to the carrier. Page’s flight was headed south and could have followed the strikers out, but Page said, “Let’s make one more pass north.”

“We came around the corner and there they were: two targets, 37 miles,” recalled Batson. “Both RIOs seemed to obtain contact at the same time. Page said something like, ‘Going into fighter role.’ I did a big ol’ lazy barrel roll to get into trail position and we accelerated to 500 knots.”

With the oncoming North Vietnamese aircraft, which turned out to be MiG-17s, flying at about 400 knots, that 37 miles would shrink rapidly as the fighters and bandits closed at more than one mile every four seconds.

Doremus stayed in search mode while Batson “did my pilot things: turned on the CW illuminator [continuous wave radar guidance for the AIM-7], waited for green lights, then turned on master arm and fuel transfer. I made a good cockpit sweep and then got my head back out.” Doremus provided updates while Batson flew off Page’s Phantom, three miles ahead.

The naval aviators were acutely aware that most of the airplanes flying over North Vietnam were American, and they needed to adhere to the VID requirement before shooting.

Working his radar, Smith saw two blips, meaning two targets in trail formation. Implementing their plan, he locked onto the trail target and told Doremus to lock the lead, which they confirmed by radio.

Batson recalled that the morning air was clearer than usual, and he had a tallyho at 10 miles on “four little specks,” not two. “I experienced the clock slowing down,” he said. “I felt very comfortable, it was an amazing feeling.” His 800-plus flight hours in the F-4 doubtless contributed to his confidence, an important factor as the converging aircraft covered the 10-mile separation in less than 40 seconds.

Smith drove the intercept to give the Phantoms lateral separation, putting them about a mile east of the MiG-17s’ flight path. As they approached the merge, the lead MiG rolled left to come nose on, with his wingman in tight formation. Page saw the distinctive shape of the wings, made his radio transmission of “It’s MiGs!” and squeezed the trigger.

Batson observed the launch and knew lead’s missile was guiding. He saw the warhead explode and “nothing happened for what seemed like a long time.” Credit time distortion. He thought it was a miss…until the MiG’s right wing came off.

Doremus intently monitored the radar steering cues: a circle that expanded and contracted based on factors such as speed and angles, and a dot that indicated where to fly. When the dot was in the circle, the crew had a valid shot.

The crew later determined that the lead MiG, which Batson and Doremus were locked on, tried a wingover turn. This led to the “pull up!” call. At those speeds and close range the geometry changed quickly, so the calls to “fly the dot” and “go down” weren’t unusual. At the optimum range, when the circle was biggest, Batson squeezed the trigger. Launch range was about three miles.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

NE102 was carrying two Sparrows on belly stations and one on the right wing. On the left wing were two Sidewinders. When Batson squeezed the trigger, the Sparrow on his wing roared to life and zoomed off its rail. Though the missile was 12 feet long and weighed 400 pounds, he didn’t see the launch. “I was busy flying,” he said. “I was concentrating on keeping the target illuminated [by radar]. I did see an explosion, then I lit the afterburners and pulled up as we planned.”

Reorienting his brain to the next phase of the plan, Batson looked up to find his lead. “There he was, right above me. Thank you, Lou Page. I saw his afterburners wink off, rendezvoused on him and we dove back to the area of the engagement.”

There they sighted the smoke trails from both missiles—a memorable image—and Smith saw one parachute.

Batson checked his instruments and radioed Page that he was below bingo fuel (the amount required to return to the carrier). They started a bingo profile (climb, cruise, descend) and Midway vectored a tanker, which Page declined. But there were no victory passes for this pair: Batson was detached for a straight-in approach and landed with 500 pounds remaining, which is low for an F-4 and carrier ops. Page turned downwind and landed; he also had to be low on fuel.

During the flight back to the ship, Batson was “in the moment, still flying,” but the Midway crewmen knew they had scored kills. As they climbed down from their fighter, Doremus turned to Batson and said, “Four more to go!” (to make ace).

The Phantom crews were greeted by cheers as they walked to their ready room, and Page was diverted to the flag bridge (a level in the ship’s island where an admiral and other VIPs could observe ops). In a fortuitous coincidence, Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze was visiting Midway that day, and a photo shows him congratulating Page, who is still in his flight gear.

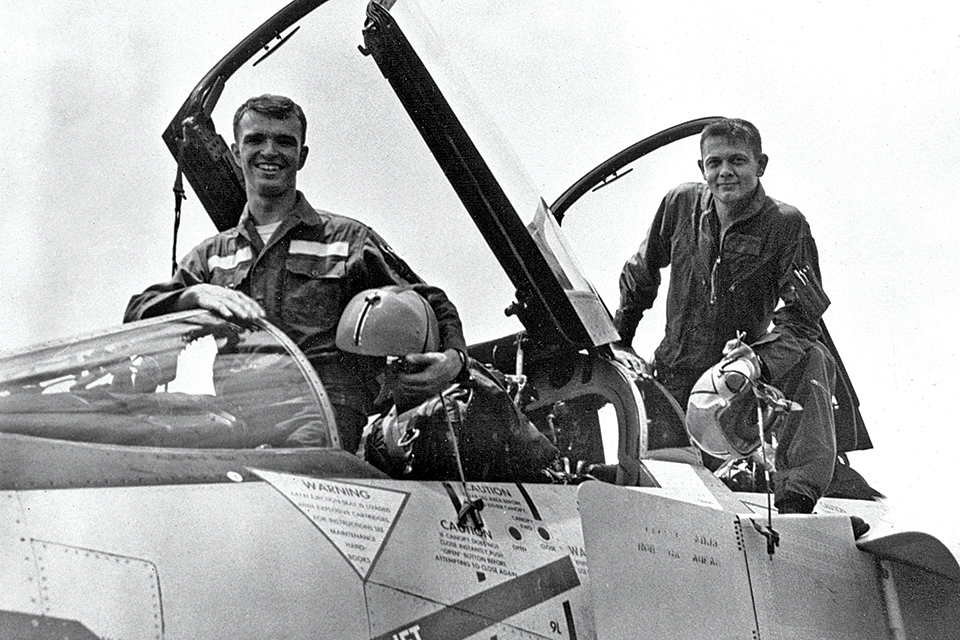

VF-21’s maintenance chief petty officer ensured the aviators completed post-flight forms, after which the aircrews debriefed with intelligence personnel, both normal activities after carrier flights. But then events veered from the normal. A photo shows the crews holding squadron coffee mugs while discussing the flight. Batson revealed that they were filled with “medicinal” brandy.

The shipboard celebrations were short-lived, however, as the crews were told to grab clean uniforms and get back in their same jets to fly to Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon for the daily press briefing, the “five o’clock follies.” They were met by public information officers from all services and noticed that the Air Force PIO seemed unhappy. When the aviators asked if it was because the Navy got the first confirmed MiG kills, the blue-suiter replied, “No, it’s because we were going to announce the first strike by B-52s and you guys stole the headlines.”

He was right: Many friends sent newspaper front pages to Batson’s parents, and the VF-21 MiG-kill story was top-center. The Navy had scored the first confirmed American air-to-air victories of the Vietnam War.

The shooters soon returned to normal combat operations. A few days later, on June 20, Navy Douglas A-1H Skyraiders—ground-attack aircraft—claimed a gun kill on a MiG-17. They were Midway–based A-1s at that. Batson quipped, “Imagine if they’d gotten the first kills!”

Rob Doremus was shot down on August 24, 1965, while flying with VF-21 skipper Bill Franke. Their wingman did not see any parachutes and no beepers were heard (ejection seats have small radios that transmit upon ejection), so the pair was declared killed in action. Dave Batson was devastated by the loss of his friend. After attending Doremus’ funeral, he pulled himself together and continued fighting the war, though the loss remained with him. Two years later the North Vietnamese released a list of POWs and both Doremus and Franke were on it, a huge relief to their squadron mates. The pair suffered in captivity for 7½ years, and were finally released in 1973.

After the deployment, Batson planned to attend the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., to pursue a master’s degree in computer science. The Navy cajoled him into first going to the training command as an instructor “for just one year.” When the year was up, Navy detailers, doubtless swamped by the war’s demands, doubled down on the training command orders, but Batson exercised his option to leave. He had served his country, and done his duty well.

Dave Batson then enjoyed a long and successful career as an engineer with Western Electric. His years of naval service with talented teammates, not to mention his MiG kill, gave him the best story around the coffee pot.

Other Claims and Probables

Relatively recently it has been determined that U.S. Air Force North American F-100D Super Sabre pilot Captain Donald Kilgus “probably” got a gun kill on a MiG-17 on April 4, 1965, during one of the first aerial engagements of the war. Aces and Aerial Victories, a 1976 publication by the Air Force Office of History, did not mention this possibility in its account of the event, saying MiGs “downed two [F-105s] with cannon fire and escaped at high speed.” Author Robert F. Dorr, however, made a strong case for the kill in a 2014 online article.

A few days later, on April 9, Navy F-4 crews from VF-96 engaged Chinese Shenyang J-5s (license-built MiG-17s) near Hainan Island. Author Michael O’Connor describes the incident in MiG Killers of Yankee Station, highlighting the confusion and frustration surrounding the engagement and debrief. Some sources credit Lieutenant Terry Murphy and Ensign Ron Fegan, who were lost during the fight, with a MiG kill that day, but it is best described as uncertain.

As for the VF-21 engagement on June 17, author O’Connor writes: “In 1997 declassified documents confirmed that a third MiG had fallen,” and it was credited to Batson/Doremus. When asked about it, Batson brushed it off, instead preferring to focus on the preparation, performance and teamwork that characterized the mission.

Dave Baranek was a Grumman F-14 Tomcat RIO and Topgun instructor. His third book, Tomcat RIO, will be published in August. Recommended reading: MiG Killers of Yankee Station, by Michael O’Connor, and US Navy F-4 Phantom II Units of the Vietnam War 1964-68 and USN F-4 Phantom II vs VPAF MiG-17/19: Vietnam 1965-73, both by Peter E. Davies.

Ready to build your own replica of Batson and Doremus’ MiG killing F-4? Click here!