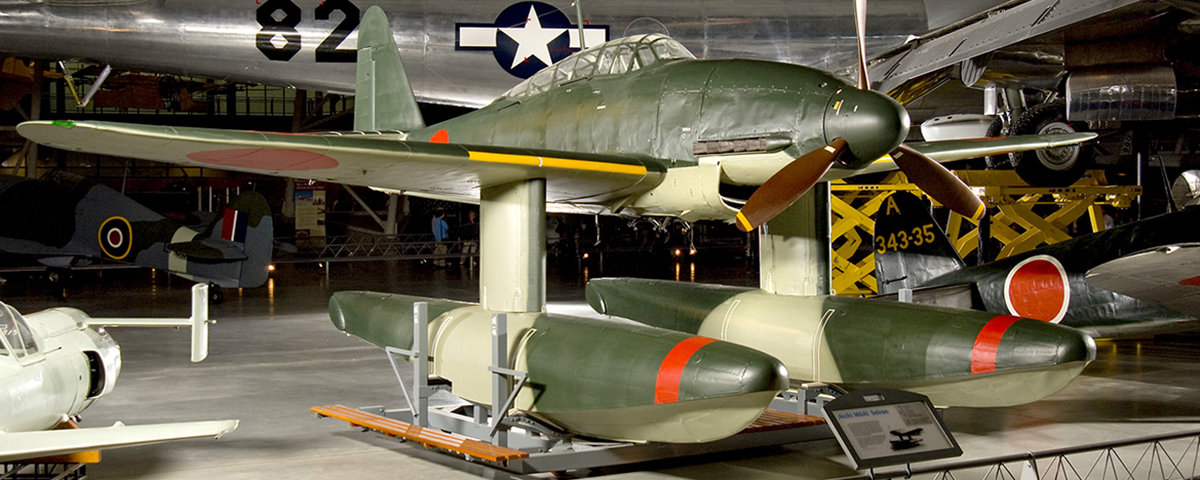

The only remaining example of an Aichi M6A1 Seiran floatplane, part of Japan’s audacious plan to launch bombers against U.S. coastal cities and the Panama Canal from I-400–class subs, is on display at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia. The floatplane bomber spent nearly 40 years in storage before Smithsonian specialists began a painstaking restoration in the late 1980s.

A typical Seiran mission would have called for the sub to surface when it neared a target, after which the crew would winch the aircraft out of a huge watertight hangar and onto a launching dolly. The plane’s wings, which were folded against the fuselage sides while it was inside the hangar, would be hydraulically rotated into flight position, and the downward-stowed horizontal stabilizers folded up, along with the tip of the vertical stabilizer. Once preflight preparations were complete, the aircraft was launched into the air by a 120-foot pneumatic catapult mounted on the sub’s deck. The whole launch sequence could be carried out by a team of up to 10 specially trained crewmen in 45 minutes or less.

As originally proposed, after a mission the bomber was supposed to return to its parent sub, where the aircrew would ditch the plane—after which they would be picked up by the sub. After further consideration, however, the Japanese determined that scuttling a perfectly good aircraft was not an efficient use of scarce wartime resources. They installed twin floats on the bombers, so the airmen could land alongside the submarine, after which its crew could hoist the plane back onboard

As it turned out, there were some serious drawbacks to the floats. They added considerable drag and weight, which reduced the Seiran’s speed and range as well as bombload.

Imperial Japanese Navy and Aichi Aircraft Company records confirm that the Udvar-Hazy’s Seiran was the last of 28 M6A1s produced. It is unclear whether this particular aircraft—known as No. 28—ever flew in combat, but it likely took part in some training flights. Robert McLean, one of more than a score of museum staff restorers and volunteers who worked on the Seiran project, said information from the Tamiya Plastic Model Company of Shizuoka City, Japan (brought to light in a recently discovered postwar telegram) revealed that a Seiran was ordered in early 1946 to fly from its training base at Fukuyama to Tokyo. Sometime later researchers at the museum received a letter from the pilot who had flown that ferry mission to Tokyo, saying that the aircraft he had flown was No. 28.

Seiran No. 28’s journey to the United States began shortly after WWII ended. The floatplane arrived in the United States along with several other examples of Japanese aircraft aboard a U.S aircraft carrier later that year. Records show the plane was put in storage at Alameda Naval Air Station, where it was also occasionally exhibited.

In November 1962, the Seiran was shipped from California to the Smithsonian’s Silver Hill, Md., site (later known as the Paul E. Garber Restoration Facility), where it was stored until the late ’80s. Restoration specialist Matthew Nazzaro noted that when the restoration project started, team members had little documentation to guide them: “Archives had only one sketchy blueprint, and that was the extent of the collection of information that was available to us.” But as the project got underway and word of the restoration got around, information began flowing to the museum from Japan.

One valuable resource was Hiroyuki Nagashima, who volunteered his time at the Smithsonian’s workshop for more than six months, translating Aichi documents. Nazzaro explained: “He also provided us with a resin model kit [of a Seiran] produced in Japan. On that kit’s instruction sheet were a number of factory photographs and quite a bit of information on the aircraft’s components.”

Another significant source of information was Tetsukuni Watanabe, a retired quality assurance engineer from Aichi Machine Industry, the aircraft company’s present-day successor. According to McLean, Watanabe’s interest in the firm’s aircraft production had led him to become a de facto expert on all the planes produced by Aichi during WWII. Thanks to his close ties to the manufacturer, as well as his friendship with the son of Seiran designer Toshio Ozaki, Watanabe was able to provide the restoration team with information that otherwise would not have been available.

Period photographs of the cockpit are rare, and documentation for that portion of the plane is largely nonexistent—all of which made the restoration especially challenging. A photo of the cockpit instrument panel on the model instruction sheet provided by Nagashima resolved some questions.

In an effort to keep as much of the aircraft as original as possible, the cockpit interior paint was cleaned to remove the haze of oxidation, then coated with a preservative. A number of the instruments and gauges were missing and had to be replaced. Those that were not available from the museum’s collection of Japanese artifacts were replicated from original drawings or examples in the facility’s collections. Other parts were donated or were purchased from collectors. The interior of the pilot’s cockpit is now virtually complete, including the reflector bombsight that was hastily installed on No. 28 sometime before its flight to Tokyo. Archival photos show that other Seiran models used an older style telescopic sight.

When it came to the navigator/gunner’s position, a replica of the chart table was fabricated in the museum’s wood shop, using plans from a microfilmed copy of the Japanese navy’s instrument standards manual. Also missing from the rear cockpit was the drift sight. The museum’s machinist, George Vencelov (now retired), constructed an exact copy of this complicated instrument, using the original in the museum’s collection as a pattern. McLean and Nazzaro pointed out that the navigator’s station is complete down to the mount that holds the airman’s watch. (That tiny detail became important when a benefactor recently donated an original Seiko Imperial Japanese Navy navigator’s timepiece.)

The hulls of the floats had been damaged because they had been stored outdoors for many years. “They had filled with water,” Nazzaro explained, “and it rotted out the keels.” About 90 percent of the original metal had to be cleaned of corrosion and treated before being reassembled.

Early on, experts had inspected the Aichi Atsuta 30 series engine, which was in good condition. The 1,400-hp Atsuta was a Japanese second-generation development of the German-designed Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine. The team knew that No. 28’s engine ran for at least a few hours during the plane’s ferry flight, but how many hours it ran prior to that is anybody’s guess.

Most of the linen covering the control surfaces was missing. To ensure the restoration’s authenticity, the team decided that in replacing it they would replicate the stitching on the museum’s B7A Ryusei, or “Grace,” the only other Aichi in its collection. “I did the fabric on the rudder and the elevators,” Nazzaro recalled. “There was quite a bit of corrosion, and I had to replace some of the sheet metal parts as well.”

Once the aircraft’s basic structure had been rebuilt, it was time to dress the Seiran in colors that were as authentic as possible. McLean and Nazzaro pointed out that a great amount of misinformation has been published about the colors used on Japanese WWII aircraft. With that in mind, they decided that “the paint that was on it was the best guide for how it should be repainted,” according to McLean.

Selecting the colors came down to carefully matching paint that had been preserved in certain protected areas of the aircraft. “We found some very good examples of the lighter color underneath the horizontal stabilizer that I thought was virtually in perfect condition,” Nazzaro said. In keeping with their plan, the underside surface of one of the stabilizers was not repainted, but was left as is, preserved with a museum-approved clear acrylic coating.

Most of the top color had oxidized and could not be saved. The replacement top color was carefully matched to samples taken from protected areas on the fuselage. The “break line” between the top and bottom colors was clearly evident on the airframe, and restorers managed to match it exactly as it had been when the plane left the factory.

One of the most noticeable missing parts was the spinner fitted on the front of the three-bladed propeller. When the aircraft was displayed in California, a makeshift substitute had been taped to the nose. The museum had the spinner base and most of the hub parts, but the rest was missing. Using photo analysis and measurements taken from a Yokosuka D4Y1 Suisei dive bomber, workers produced a new spinner with a somewhat different profile than that of the Suisei.

At the Smithsonian’s invitation, Seiran pilot Atsushi Asamura visited the museum to see the restored floatplane. While the 86-year-old former lieutenant was sitting inside its cockpit, he was asked whether he’d like to fly it again. Asamura laughed and shook his head, saying he was too old for that now.

Looking back on the Seiran project, the restorers describe it as a “huge team effort.” They agreed that it was especially satisfying work due to the plane’s complexity and unusual nature, but also because of the valued friendships they established with experts abroad during the process.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2008 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!

Read how the author “restored” his own Seiran in our modeling feature!