Nobuo Fujita aimed to kill Americans in a fiery blaze, but his actions yielded a far different result.

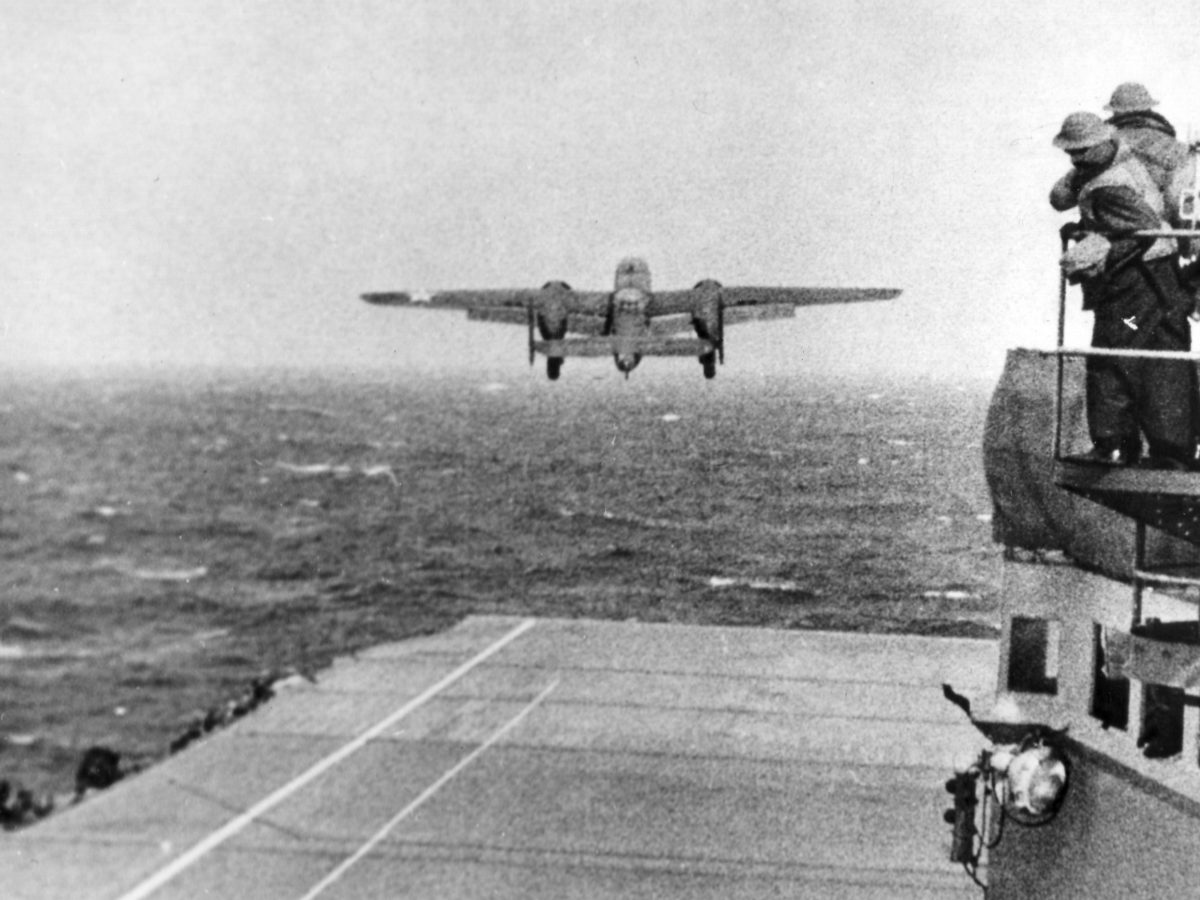

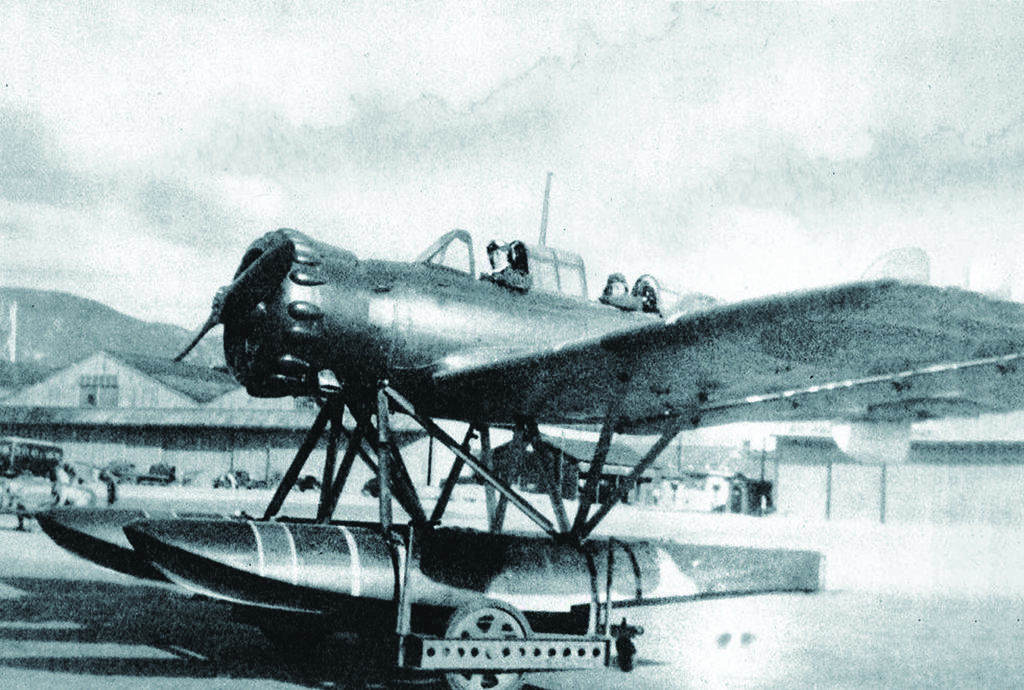

JAPANESE SUBMARINE I-25 bobbed in the ocean swells 33 miles off the Oregon coast as the submarine’s crew wrapped up flight preparations. It was the early morning of September 9, 1942; from the cockpit of his floatplane aboard the sub, 31-year-old Warrant Flight Officer Nobuo Fujita watched as a faint orange glow suffused the eastern horizon. Before sliding the canopy closed, he reached down to pat the ancestral samurai sword stowed beside his seat—a talisman always by his side on operations. At 5:35 a.m., the catapult officer pulled the launch lever and the little Yokosuka E14Y shot into the air.

As Fujita gained altitude, he could begin to make out the undulating contours of the Klamath Mountains. It was there that he was headed; there that he intended to drop the two incendiary bombs mounted beneath his wings. His mission was nothing less than to set southern Oregon’s vast, virgin forests of Douglas fir ablaze in hopes of creating an unstoppable maelstrom that would devastate the region, destroy towns, kill people. It was Japan’s intention to spread panic among mainland Americans by demonstrating that the empire could bring the war directly to their doorsteps. If he pulled it off, he’d be the first person to ever bomb the Lower 48.

NOBUO FUJITA stood barely five feet tall. His chiseled face revealed a calm, confident countenance. Born in 1911 on a farm in central Japan, he was conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in 1931 and after boot camp went to the Kasumigaura Naval Air School. In the mid-1930s he tested experimental seaplanes and in 1937 served six months in China flying rescue missions along the Yangtze River. He returned to Japan the following year as a flight instructor, joining the submarine aviation unit in 1941. Before deploying, his father entrusted him with the family’s precious, centuries-old sword.

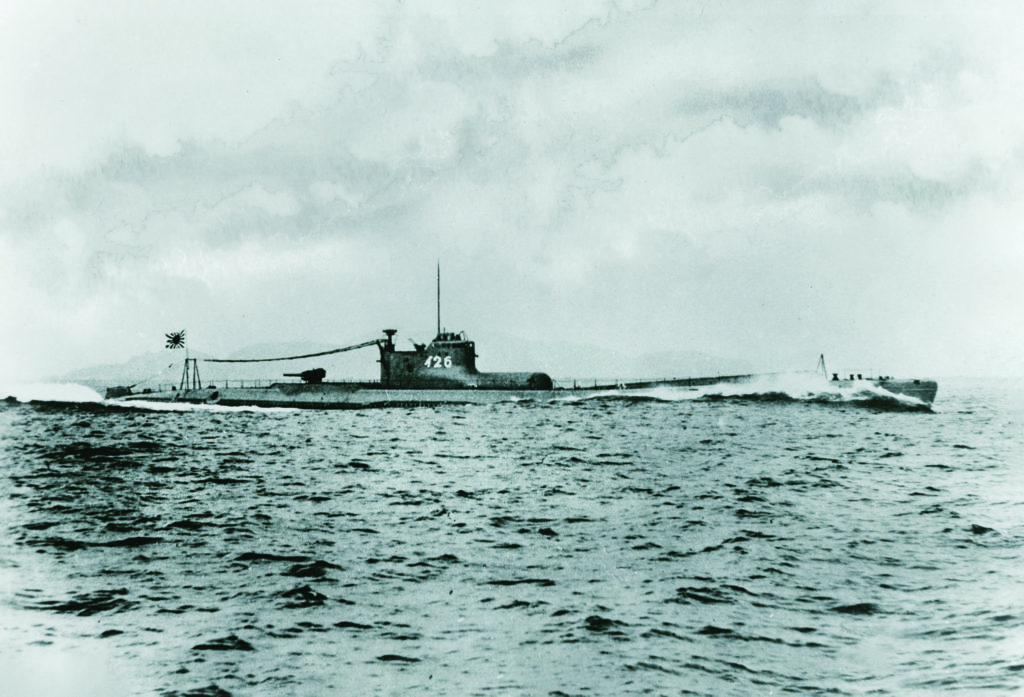

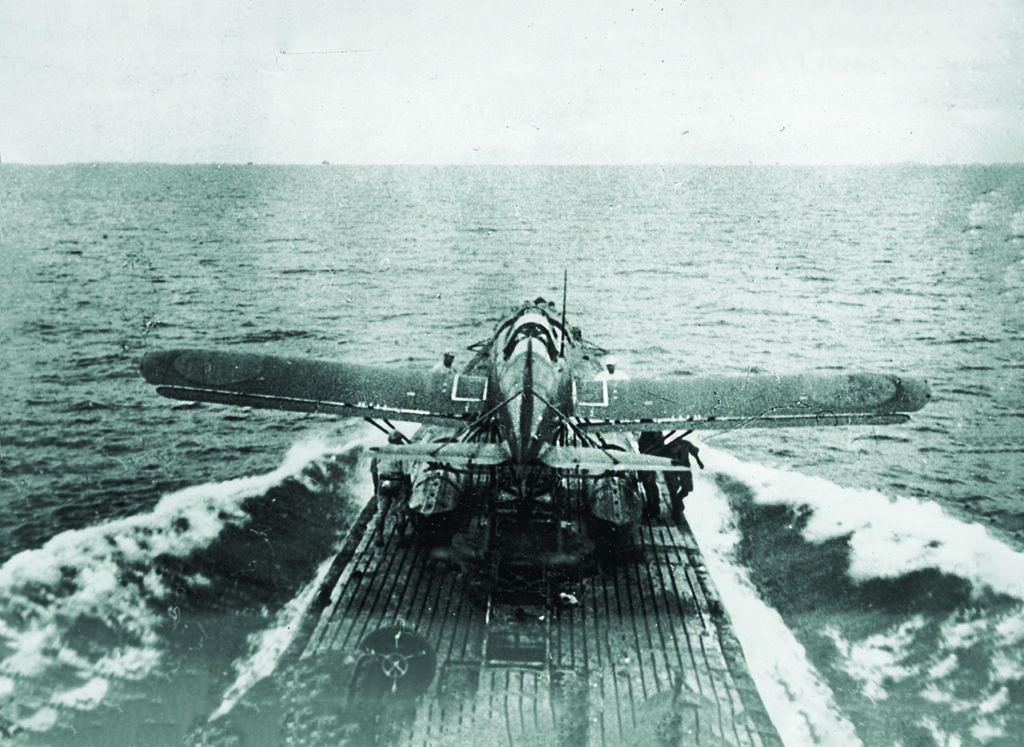

Fujita’s launch platform, submarine I-25, was one of 29 “Type B” boats designed to carry a small reconnaissance plane. The thinking behind these submersible aircraft carriers was that the plane would extend the sub’s scouting range by hundreds of miles. Though other nations had conducted similar experiments before the war, the IJN was the only major power to deploy them.

The Type Bs were powerful submarines, superior in many ways to the American Gato class, the standard U.S. fleet submarine at the beginning of the war. They were, at 356 feet in length, 45 feet longer; weighed 1,100 tons more; had a range of 14,000 miles—3,000 more than the Gatos; and with a top speed of 23.5 knots, could outrun them. The E14Y “Type 0” seaplane—a low-wing, two-seat monoplane with a top speed of 150 mph, range of 547 miles, and bomb load of 336 pounds—was carried in sections inside a streamlined steel hangar just ahead of the sub’s conning tower. A seven-man aircrew could assemble its 12 components in about 15 minutes and launch it from a compressed-air catapult on the foredeck.

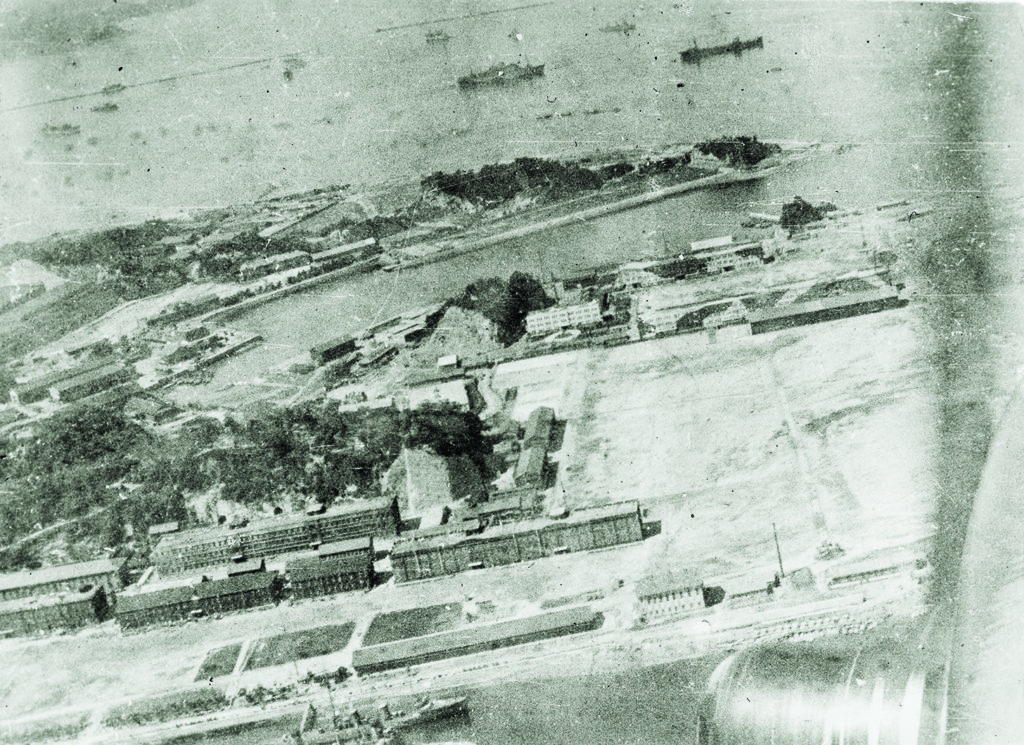

On November 21, 1941, I-25 left Japan’s sprawling Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, 30 miles south of Tokyo, to join a 27-boat force en route to Hawaii to support the IJN’s First Air Fleet for its attack on Pearl Harbor.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1941, proved to be a peaceful day for I-25. It was stationed 140 miles northeast of Oahu with a trio of other subs on the lookout for any American ships trying to escape the chaos at Pearl. Instead of being at the controls of his airplane, searching the seas for fleeing enemy ships, pilot Fujita was relegated to stand regular watches in the ship’s control room, a duty he found a waste of his valuable flying skills. A more promising assignment emerged one week later, when the crews of nine of the 27 subs received exciting news: they were to sail to the United States’ West Coast to take up positions off strategic locations from Seattle to San Diego and seek out targets of opportunity.

It was during this ocean transit that Fujita conceived of a way for Japan’s aircraft-equipped submarines to make a more valuable contribution to the war effort. He reckoned that instead of just scouting, the planes—already armed with bombs—could fly well ahead of the subs to go on the attack, striking Allied shipping, Panama Canal locks, or aircraft factories along the West Coast. He shared his vision with the ship’s executive officer, who encouraged him to send his idea to the IJN High Command. “I laughed,” Fujita recalled. Who “would listen to a mere farm boy?” But he wrote it up anyway, and the officer promised to forward it to headquarters.

In the meantime, Fujita executed his duties while itching for more. I-25 reached its post—the mouth of the mighty Columbia River marking the border between Oregon and Washington—on December 18. The IJN had a special holiday treat in mind for American citizens: a Christmas Day bombardment. The group of nine was ordered to fire 30 shells each at West Coast targets of their choice.

Then the IJN received intel that the U.S. was sending reinforcements through the Panama Canal; they canceled the shelling at the last minute and instead redeployed all nine subs to intercept the incoming American vessels near Los Angeles. But the intel was faulty, the enemy did not appear, and the group was instructed instead to sail to the naval base at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. After a refit there, I-25 embarked on a mission more to Nobuo Fujita’s liking: an aerial reconnaissance of harbors in Australia and New Zealand to determine the numbers of Allied ships at each place.

On February 17, 1942, in the predawn darkness 100 miles southeast of Sydney, Fujita’s Type 0 was ready to launch. Just after 4:30 a.m., as the submarine cut through the sea at 18 knots, he took off. He throttled back and for the next hour flew at 90 knots on a northwest heading toward the Australian mainland. He crossed over the beaches at Botany Bay on the south side of the city, then made a slow, wide arc above Sydney Harbor. While the pilot kept a watchful eye for enemy fighters, his observer, Petty Officer Shoji Okuda, made a careful plot of the ships he saw below him—23 in all, including several warships. By then the sun was beginning to rise, and the pair grew anxious that Sydney’s antiaircraft defenses would spot their plane. As Fujita later recalled, “We were in constant fear of discovery.” To their relief they weren’t spotted over Sydney and, by 7:30 a.m., the plane was back in its hangar and the flight crew sat snugly in the mess sipping cups of hot tea.

Recommended for you

During a flight they made over Melbourne in early March, their aircraft was discovered twice—first by the Royal Australian Air Force, which scrambled two fighters that were unable to locate it, then by an antiaircraft gun crew, who were still seeking permission to open fire when Fujita unknowingly flew out of range. The reconnaissance of Tasmania, New Zealand, and Fiji went smoothly.

The following month, I-25 was awaiting routine repairs in drydock back at Yokosuka when a flight of American B-25s suddenly appeared from out of the east. It was April 18, 1942; Doolittle’s raiders had come calling. I-25, a sitting duck, was not hit, though other ships around it sustained serious damage. It was a sobering experience for Fujita, and he vowed to seek revenge.

He flew again at the end of May during I-25’s third war patrol, this time to scout military facilities at the American base at Dutch Harbor, Alaska, in advance of the Japanese invasion of the Aleutian Islands on June 3. He was set to go when a faulty valve on the catapult mechanism prevented launch. Just then, lookouts saw an American cruiser steaming on a parallel course barely a mile away. I-25 couldn’t submerge—the plane was still on deck—so the captain prepared to shoot it out. He would have been murderously outgunned, but after a few tense minutes the enemy warship instead turned away. The faulty part repaired, Fujita made a reconnaissance flight the next morning. Then I-25 sailed southeast toward the Oregon coast for the second phase of its mission.

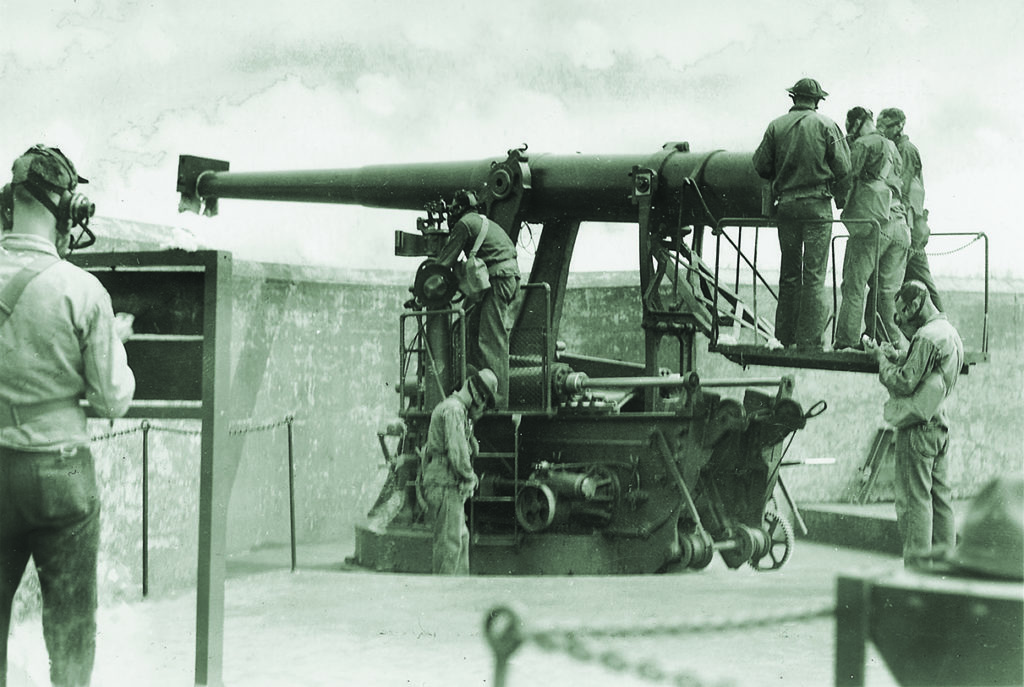

On June 21, the submarine was again at the mouth of the Columbia River, this time with orders to shell the submarine base at Astoria in the far northwest corner of Oregon. And once again, Japanese intelligence proved faulty—there was no such base. It’s unclear what I-25’s captain thought he was shooting at that night, but he lobbed 17 5.5-inch rounds shoreward. Most of the ordnance fell harmlessly on the grounds of Fort Stevens, a Civil War-era coastal defense battery (see “Ready, Aim, Silence,” October 2017—online as “Built During the Civil War—But Shelled by the Japanese”). To Fujita’s chagrin, his Type 0 stayed tucked away in its hangar the entire time and the attack only modestly rattled local residents. Mrs. Archie Reikkola told the La Grande Observer: “The raid was over before we got scared.”

NOBUO FUJITA WAS LOOKING FORWARD to seeing his wife and young son when I-25 returned to Japan in mid-July 1942. But as soon as he landed, word came that he was to report immediately to Naval Headquarters. He wondered if he was he going to be called on the carpet for some infraction: “I was very nervous.” Instead, as he entered an inner office, he was stunned to see Prince Takamatsu, Emperor Hirohito’s younger brother. Another officer, a Commander Iura, began the meeting. “Fujita, you are going to bomb the American mainland.”

“I was speechless. My mind considered Seattle, Portland, San Francisco. Perhaps I could hit a carrier. The whole thing seemed like a dream.” Another officer shook the pilot from his reverie; Issaku Okamoto, a former vice-consul for Seattle and an expert on the Pacific Northwest and its history of wildfires, pointed to a map of Oregon and said, “You will bomb these forests.” Fujita was crestfallen, thinking to himself, “Any cadet could bomb a forest! What did they need me for?”

Noting the flyer’s dismay, Okamoto explained the rationale: the region is full of trees. “Once a fire gets started in the deep woods it is very difficult to stop. Sometimes whole towns are burned.” He had in mind a September 1936 conflagration that destroyed 287,000 acres of Oregon forest and wiped out the coastal town of Bandon, killing 11 people. Aside from grabbing Americans’ attention and causing panic, the best-case scenario for the plan would be to force the U.S. to divert naval resources—then concentrated at the Solomon Islands—to the West Coast. He added that the mission was “very important and urgent.” That made Fujita feel a little better.

SURFACED 33 MILES OFF Oregon’s Cape Blanco lighthouse—its beam still burning brightly despite a coastal blackout—I-25’s deck swarmed with activity in the morning darkness of September 9, 1942. Before going up to his plane, Fujita placed a strand of his hair in a small wooden box. “If I were to die and my body could not be recovered, these ‘remains’ would be sent back to my wife,” he recalled, adding, “The mission scared the daylights out of me. I did not think I would come back alive.”

After taking off, Fujita’s floatplane climbed slowly toward the mountains. “I thought how beautiful the sunrise was as it gradually climbed above the ridge of the mountains,” the flyer said. Each of his two 168-pound incendiary bombs housed 520 thermite pellets that, when triggered, burned at over 2,700 degrees. Mother Nature would supply the tinder. As he neared land, the pilot banked to the southeast, flying over the sleepy lumbering town of Brookings. Ahead, standing well above a patchy fog, stood 2,925-foot Mount Emily. Approaching the summit, Fujita turned again to the southeast and, when the plane was about three miles from the mountain at a height of 500 feet, he ordered Okuda to drop the first bomb on the dense forest below.

“We watched carefully,” he recalled. “Moments later we saw the scattering of flickering fires. It gave me great satisfaction to get some revenge for the bombing of my homeland by Doolittle’s raiders.” After dropping the second bomb, Fujita took his plane down to treetop level and flew back for his rendezvous with I-25.

JUST PAST NOON, Howard M. “Razz” Gardner, a Forest Service fire lookout, was scanning the horizon with his binoculars from a tower on Mount Emily’s peak when he spied a white plume below him in the woods. He radioed into headquarters: “A Smoke. Township 40 South, Range 12 West, Section 22.” It was his second radioed alert of the day: at 6:15 that morning, while making breakfast, he had heard a sound he described as “a Model A Ford backfiring.” Then he saw a plane circling. He was unable to identify its type, but to be on the safe side, Razz radioed headquarters. No one there was alarmed, so he finished his bacon and eggs. Now, he got more of a reaction: head ranger Ed Marshall called back and ordered him to start toward the fire. The chief notified three other foresters to get a move on, too.

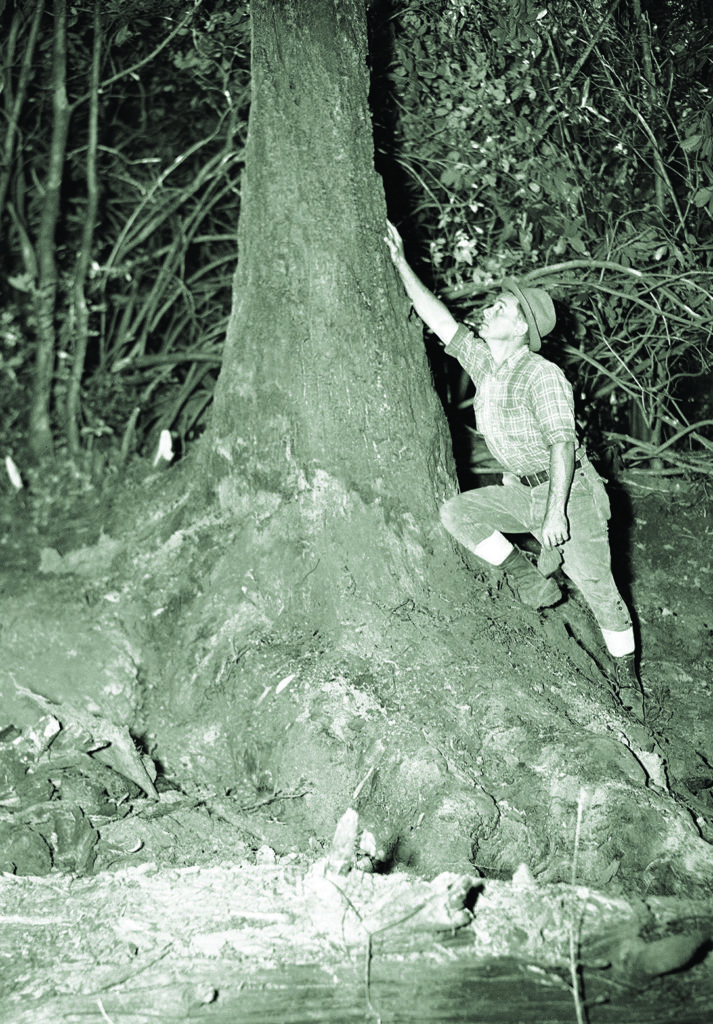

It took Razz three-and-a-half hours through the forest fastness, with only his compass to guide him, to reach the site at Wheeler Ridge. Upon arrival, he was amazed by what he saw. It wasn’t just a single fire, but dozens, all burning brightly. Right away, he got to work with his shovel and axe to clear the brush; the others arrived shortly after. One of the men noticed what he thought was a crater. It was about three feet across and 18 inches deep. He called out, “Hey, somebody dropped a bomb here.”

The crew found metal fragments in a radius of 50 feet, some melted into lumps by the intense heat. “By God,” a firefighter said, “There’s enough stuff here to have set the whole of Curry County on fire.” Which was, of course, the IJN’s devilish plan. But it had been foiled by a rainstorm that inundated the woods the night before, curtailing the fire’s spread. Fewer than half of the thermite pellets had exploded, likely due to the damp conditions.

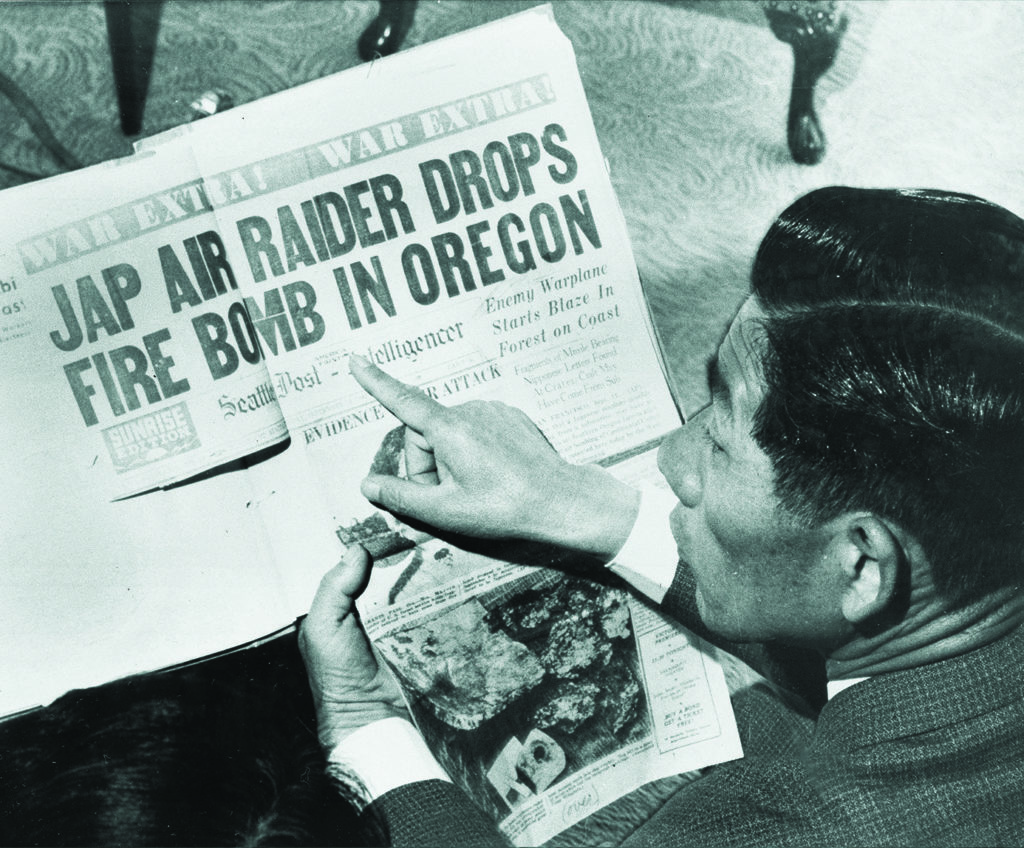

The bombing made headlines in Japan. The September 17, 1942, edition of Asahi Shimbun blared, “Incendiary Bomb Dropped on Oregon. First Air Raid on Mainland America. Big Shock to Americans.” The attack also made front-page news across the U.S., from Oregon’s Coos Bay Times to the New York Times, but no panic ensued. And when Fujita undertook a second bombing mission nearly three weeks after the first—this time near Port Orford, 50 miles north of Brookings—the results were the same as before: nil.

Beginning early the next summer, Fujita spent the remainder of the war assigned to a flight school to train kamikaze pilots. When he was mustered out in 1945, he believed he had served his country well and loyally; still, he was disappointed he never received any appreciation for his wartime achievements: “no promotion, no bonus, no glory.” So he didn’t particularly mind when a U.S. Navy journalist, Joseph D. Harrington, tracked him down in suburban Tokyo in 1960, where the former floatplane pilot was raising a family and running a hardware store.

Harrington had heard about Fujita’s exploits while working on an English translation of a book about Japanese suicide submarines; he persuaded Fujita to coauthor an account of his attack for the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine. The result, “I Bombed the U.S.A.,” was published in the June 1961 issue. Satisfied that he finally got at least a modicum of recognition, Fujita probably thought that was the end of it.

ABOUT THAT SAME TIME, 5,000 miles across the Pacific, three Junior Chamber of Commerce members from Brookings, Oregon, were returning home from a road trip to the Jaycee state convention at Pendleton. During the 10-hour drive, the trio got to talking about what kind of community project their chapter could take on that would be “beneficial in putting Brookings on the map.” Many ideas were tossed about and out.

Then Doyle Rausch told his friends about the 1942 Japanese bombing of the forest outside town. None of the others had ever heard of the incident. “I was absolutely flabbergasted,” town dentist Bill McChesney later told filmmaker Ilana Sol, creator of the 2019 documentary Samurai in the Oregon Sky. “I wonder if this fellow is still alive?” Doug Peterson suggested that maybe they could track down the pilot and “ask him back as our guest.” If they succeeded, it would be a gesture of international peace and friendship that fit right in with the Jaycees’ creed: “The brotherhood of man transcends the sovereignty of nations.”

In autumn 1961, Nobuo Fujita, then 50, got the surprise of his life when an invitation to be the guest of honor at the 23rd Annual Brookings Azalea Festival arrived at his doorstep. The event was scheduled for the following May. The former foe accepted with cautious optimism—but fear, too, for many townsfolk opposed the visit. A local veterans group wrote: “To us, an invitation to Fidel Castro or erecting a monument to John Wilkes Booth would be just as sensible a project.” Bill McChesney, then president of the chapter, even received a midnight death threat.

But the Jaycees voted as one to push ahead. Fujita was so unsettled about what might happen in Brookings that he wrote afterward: “I was quite sure I would be beaten up; people would throw eggs and shout insults.” He even wondered if he might be tried for war crimes. Those fears were assuaged when the Jaycees received letters of support for the visit from Oregon governor Mark O. Hatfield and President John F. Kennedy. Just before Fujita and his family appeared, the local police took the precaution of jailing some of the loudest dissenters—including Razz Gardner, the man who first spotted the fire.

On May 24, 1962, Nobuo Fujita, his wife Ayako, and son Yasuyoshi arrived in Brookings. They were presented with the key to the city and the next day rode at the head of the Azalea Festival Parade. They enjoyed a crab feast and an outdoor church service. A special treat was in store for Nobuo and his son that afternoon—they climbed into a Piper light aircraft and flew over Mount Emily and the forest he had tried to set afire two decades before. When asked if he would like to take the controls, Fujita eagerly accepted. The next evening the town held a grand banquet for the Japanese family.

Fujita had a surprise of his own for the people of Brookings. “This is the finest way of closing this story,” he told his rapt audience. “It is the samurai tradition to pledge peace and friendship by presenting a sword to a former enemy.” His son then handed to Mayor C. Fell Campbell his family’s 400-year-old samurai sword—the same one Fujita had carried during the war.

Over the next three decades, Nobuo Fujita made several more visits to the town, donated books about international relations to the community, and hosted a visit to Japan by a group of high school students. Just a week before he died, in September 1997, warrior and friend Fujita was made an honorary citizen of Brookings, Oregon. The following year his daughter, Asakura, visited the bombing site in the shadow of Mount Emily to spread some of his ashes. She said of her father: “He felt his soul would forever be flying over the forest.” Today, his sword still holds its place of honor in the main reading room of the town library. ✯

This article was published in the June 2020 issue of World War II.