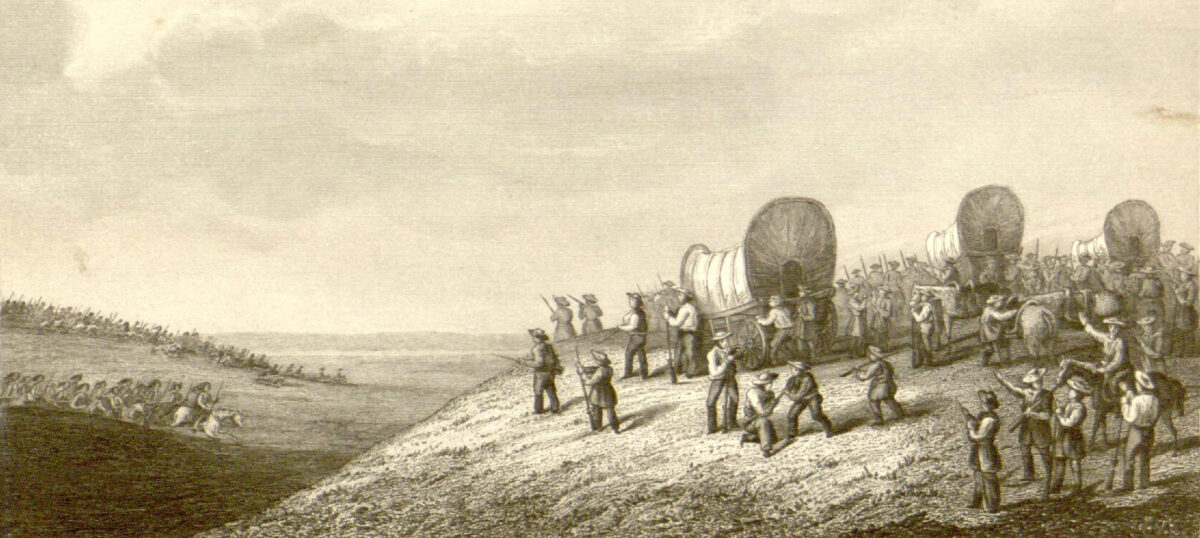

On the morning of June 19, 1841, the Santa Fe Pioneers were ready to depart Kenney’s Fort, an outpost on the banks of Brushy Creek, north of Austin, the new capital of the Republic of Texas. After a review and address by Mirabeau B. Lamar, the republic’s second president, a convoy of 24 ox-drawn wagons, 321 men, a herd of beef cattle, a 6-pounder brass field gun and about $200,000 in trade goods headed toward the wilds of northwest Texas, bound for Santa Fe.

Organized at Lamar’s direction, the expedition was charged with opening trade with Santa Fe, a growing commercial center controlled by Mexico. The trip also was designed to cement Texas’ claim to a large swath of territory east of the Rio Grande, including Santa Fe, with expedition leaders instructed to invite (but not try to compel) New Mexicans to join the republic. Lamar hoped the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, as it’s known today, would be the first step toward establishing an empire that would stretch to the Pacific Ocean.

It was not.

The expedition failed miserably. Poorly planned and led, it fell apart bit by bit as it crossed the wilderness. Men were killed in Indian attacks and spent much of the journey near starvation. The column lost most of its livestock, supplies and wagons. Survivors were readily captured by Mexican troops, sent on a forced march and imprisoned in Mexico. Perhaps 60 members of the group died, deserted or simply vanished during the 3,000-mile odyssey.

Lamar was strongly criticized for the debacle, his republic’s Congress even pondering impeachment. Yet the expedition generated renewed interest in Texas by the United States, accelerating its annexation and leading to a war that greatly increased the nation’s size, wealth and power and established the borders of the present-day state of Texas.

Born in Georgia in 1798, Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar was a man of culture. An accomplished horseman and fencer (with swords, not barbed wire), he also painted, wrote poetry and read widely. He served as secretary to Georgia’s governor, was elected to the state senate and founded a newspaper. In 1834, though, after the death of his wife and two failed runs for Congress, he decided to move to Texas.

In April 1836, at the Battle of San Jacinto, the final clash of the Texas Revolution, his quick action saved a group of soldiers surrounded by Mexican forces, earning him a promotion to colonel and leadership of the cavalry. After the revolution he became secretary of war, then was elected vice president, serving with President Sam Houston, the hero of San Jacinto.

Lamar soon broke with Houston, however, over the president’s conciliatory approach to the bellicose Cherokees and Comanches. Texas’ Constitution prohibited Houston from serving consecutive terms, and Lamar succeeded him as president, taking office in December 1838.

A strong proponent of education, the cultivated Lamar convinced Texas’ Congress to set aside public lands for schools and two universities. On the other hand, he ordered troops to drive Indians from the frontier, alienating previously friendly tribes and stirring up more violence. Partly to expand the republic’s territory and partly to needle Houston, he convinced Congress to establish a new capital on the frontier, far from the existing capital named after Houston. Lamar’s term was also punctuated by run-ins with Mexico.

His policies were costly, and public debt soared. So, the republic printed paper money worth little at first and almost nothing later on. Texas needed cash and lots of it. Lamar saw the expedition as a way to tap into the lucrative trade between Santa Fe and its partners and to convince its merchants to use Texas ports.

The president also hoped to solidify the republic’s claim to New Mexico. When captured at San Jacinto, Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna had ceded much of the territory by treaty. Texas’ Congress formally claimed the land in late 1836, but the republic hadn’t yet tried to enforce the claim.

Lamar asked Congress to authorize the expedition in 1840, and both houses seemed amenable. Lamar left the country for health reasons late that year, though, and by the time he returned, Congressman Houston had torpedoed the idea.

Undaunted, Lamar pressed on. He had reason to believe a delegation would receive a warm welcome in Santa Fe. Several trusted men who’d spent time there advised him that its people were disgruntled with Mexican rule and their governor, Manuel Armijo.

That spring Lamar had written an open letter to the people of Santa Fe, inviting them to join the Texas cause. “We shall take great pleasure in hailing you as fellow citizens,” he wrote, “members of our young republic and co-aspirants with us for all the glory of establishing a new and happy and free nation.”

Lamar appointed commissioners to carry greetings to Santa Fe and, if possible, assume control of the territory. He authorized a volunteer military force (Texas’ Congress having disbanded the republic’s army) and recruited merchants eager to ply their wares.

Lamar appointed William Gordon Cooke senior commissioner and commander of the expedition. The Virginia native had trained in the family pharmacy business before moving to New Orleans, where he joined other American volunteers off to fight in the Texas Revolution. He joined the Texas army in 1836 and at San Jacinto prevented worked-up troops from executing Santa Anna. Cooke later helped lay out roads, fought Indians, explored and mapped much of north-central Texas, and established a fort around which sprouted up Dallas.

Another commissioner was José Antonio Navarro, a Tejano—a Texan (or Texian) of Hispanic descent. He’d fought for Mexican independence but felt the Anglo-American settlers provided a better chance to develop Texas, so he sided with the revolutionaries. A signatory of Texas’ Declaration of Independence, he helped draft the republic’s constitution, was elected to its Congress and supported Lamar. He also fought for the rights of fellow Tejanos, many of whom were mistreated by Anglo settlers. Navarro would suffer more than any other member of the expedition, narrowly avoiding execution and spending more than two years in a squalid prison.

“Great troubles and sufferings”

The expedition was imperiled almost from the moment it left Kenney’s Fort. Its departure had been delayed more than a month, so the men would cross Texas at the hottest, driest time of the year. The convoy carried limited food and within days of departure had to send for more cattle. “The supply of cornmeal for bread hardly lasted over two weeks, flour or crackers we were not furnished, coffee we had only for about a month and not even salt enough

to last more than two months,” recalled 18-year-old German volunteer Cayton Erhard. Oddly, no one knew exactly where they were going, how great a distance they would cover or the obstacles they would encounter.

Even so, the journey began smoothly enough. The expedition crossed prairies, camped along creeks and rivers, dined on the abundant bison and other game, and avoided confrontations with Indians. A month into the trip, though, its luck began to turn.

“After we reached the Cross Timbers [woodlands in central Texas], then our main troubles commenced,” Erhard wrote. “In fact we were lost. Great difficulties presented themselves for advance by a rough, broken country and great scarcity of water and provisions.…We were still about 500 miles distant from Santa Fe…a very unpleasant contemplation when we had nothing to live on but poor oxen, little game and great risk of life to hunt that, on account of hostile Indians.” A popular phrase among the men was, “I’ve seen the elephant—I’ve had enough!”

Reaching what they thought was the Red River, they turned west toward New Mexico. But they were in error. The river was the Wichita, 75 miles south of the Red. “Here commenced our great troubles and sufferings,” Erhard wrote.

The expedition forged paths through dense woods, encountered uncrossable gullies and at times endured a day or more without water. On August 13, while encamped in tall grass at the edge of a ravine, a fire broke out. “The flames spread with wonderful rapidity, and in a few moments two of our wagons were on fire, one of the tents was burnt up, and the other wagons were barely saved,” recalled expedition member Thomas Falconer, a British jurist and adventurer, in an 1843 paper for Britain’s Royal Geographical Society.

On August 30 Kiowas attacked a Texan scouting party, killing five men, then stripping and mutilating their bodies. One had his heart cut out. By then, the expedition’s supplies were exhausted. Daily beef rations were cut to a pound and a half per man, bones included, and they butchered the horses killed in the Kiowa attack. The combination of long marches, little water and poor food “had combined to weaken and dispirit the men, render them impatient of control and inclined to disobey all orders,” wrote merchant George W. Kendall in his Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, the most extensive history of the enterprise written by one of its members.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The expedition’s appointed military commander, 27-year-old Brig. Gen. Hugh McLeod, had only managed to exacerbate the column’s troubles. Born in New York City and raised in Georgia, McLeod graduated from West Point, last in a class of 56. Later resigning his commission to join the new Republic of Texas, he became a general, both fought against and negotiated with Indians, and studied and practiced law.

McLeod’s command began meekly, as he fell ill soon after departure and had to return to civilization to recuperate. He was away from the party for two weeks, slowing its progress. He earned little respect as a commander, often requiring the independent-minded volunteers to drill. One officer resigned, and several men deserted. On August 31, with time and options running out, McLeod dispatched a vanguard of nearly 100 men, commanded by Commissioner Cooke, accompanied by troops under Captain John S. Sutton and equipped with most of the remaining horses and a few days’ food rations, to seek help in Santa Fe—still 300 miles away.

An Act of Betrayal

September 17 was a pivotal day for the expedition, one demonstrating that the assurances Lamar had received of a warm welcome in New Mexico had been startlingly wrong.

Mexico had deposed Santa Anna after his loss to Texas, and its Congress had refused to ratify the treaty he’d signed ceding control of New Mexico. After the Santa Fe Pioneers set out, Santa Anna had returned to office, and he regarded the expedition as an attack on Mexico’s sovereignty.

New Mexico Governor Armijo had long been preparing for a Texas incursion, petitioning Mexico City for more money and troops to protect his domain. He alerted his citizens to the potential threat and offered rewards to anyone warning of an enemy approach.

The New Mexican frontier was much farther than expected, and by the 17th Cooke’s vanguard had traveled more than two weeks instead of the expected few days. The group sustained itself by devouring “every tortoise and snake, every living and creeping thing…with a rapacity that nothing but the direst hunger could induce,” Kendall recalled. A desperate Cooke had dispatched three scouts on September 4 and five more on September 14. Both groups were captured by Mexican troops under Captain Damasio Salazar. On the 17th the second group watched helplessly as a firing squad shot two members of the first group in the back. A third Texan was killed after an escape attempt.

The rest of the vanguard surrendered that same day, thanks to an act of betrayal. As the second group of scouts was being marched toward Santa Fe, it encountered Armijo, who was leading a large force to intercept the Texans. He asked for an interpreter from among the Texans, and Captain William Lewis, who had spent time in Santa Fe, volunteered. Armijo sent him back to Cooke with a message.

Lewis was captain of the artillery and appears to have served honorably during the long journey. On September 17, however, he warned Cooke that Armijo was approaching with thousands of troops (the governor’s command was much smaller than that, though still larger and in better shape than that of the exhausted Texans). Lewis conveyed Armijo’s promise that if the Texans disarmed, they would be escorted to Santa Fe, where they could conduct their trade and return home safely. Lewis and Cooke were fellow Masons, and Lewis swore a Masonic oath that Armijo’s assurances were honest and true.

They weren’t.

On catching up with Cooke’s main column, Salazar’s men took the Texans’ arms, trade goods, blankets, money, even their coats, then bound them for the march to Santa Fe.

Some contemporaries suggested Lewis knew resistance was futile and was merely trying to save his comrades. Others said he was tricked by the New Mexicans. Most, however, thought he’d sold out, betraying his fellow Texans for his own life and a share of the expedition’s goods. Regardless, Lewis was later ostracized in both Mexico and the United States. His ultimate fate remains uncertain.

A few days prior to its capture the vanguard had encountered friendly New Mexicans who assured them villages were close by. Cooke sent messengers with the promising report back to McLeod at what the Texans called Camp Resolution, northeast of present-day Lubbock.

McLeod and party had spent a miserable couple of weeks there. At least 13 men had died of disease or in Indian attacks, and supplies were exhausted, the men having resorted to eating roasted or boiled hides from slaughtered animals. On September 15 Peter Gallagher, a 29-year-old Irish stonemason and merchant, recorded the state of things in his journal (the only diary to survive the trip): “Much discontent. The men wish to burn everything and return home. I never suffered so much in mind in my life.”

Cooke’s messengers arrived in camp on September 17, and McLeod followed them back to New Mexico. On October 4 he camped near present-day Tucumcari, there encountering forces under Colonel Juan Andrés Archuleta.

McLeod was oblivious to the fate of Cooke’s party, and his own group could muster only about 90 able-bodied men. So, on written assurances of fair treatment from Archuleta, he ordered his men to yield their arms. With that, the entire Santa Fe Expedition had surrendered without firing a single shot.

The Brutal Journey South

Archuleta escorted McLeod’s party to Armijo’s camp, where, stripped of their coats and all but a single blanket apiece, the Texans were bound together in groups. Armijo then convened a council of officers to consider their fate. “It was expected that all our men would be shot,” Erhard wrote. The council instead voted for imprisonment, and the group started on its long march south to Mexico City.

The Cooke and McLeod parties trudged into Mexico separately. McLeod’s group endured an especially brutal journey under Salazar, as recorded in Noel M. Loomis’ 1958 book The Texan–Santa Fe Pioneers. The captain scarcely fed the Texans, who were forced to march 30 or more miles a day on feet that were alternately blistered, bleeding and frostbitten. After one Texan died in his sleep, Salazar had his ears cut off as evidence for superiors the man hadn’t deserted. When another Texan with bad ankles refused to walk, Salazar summarily shot him and had his ears severed and preserved. Their only relief came when local women gave them food and water as they passed through pueblos and villages.

On October 30 the convoy entered the notorious Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man”) desert, a bone-dry, 90-mile stretch of sand, volcanic rock and thorny vegetation. Across this forbidding landscape Salazar force-marched the group overnight, providing no water and stopping only briefly to rest his horses. One Texan too weak to continue was smashed in the face with a musket and died, while another was shot.

The suffering didn’t end till they reached El Paso del Norte on November 4. “The greater number of the men were broken down by lameness and fatigue,” Falconer wrote. “Many were almost naked, and others were suffering from sickness. Immediately on their arrival everything in the power of the commandant, Colonel D. José María Elías, was done to relieve them, and assurances were given of their personal safety.”

After a few days’ rest the prisoners resumed their trek to Mexico City, where they arrived in early February 1842 and were dispersed among various prisons and asylums, including one for lepers. Some were later released, others escaped and some were abused. Finally, on June 13 Santa Anna declared an amnesty (except for Navarro, who was held in a notorious prison for 14 months before escaping). Each expedition member made his own way back to Texas.

Consequences for Lamar

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition had failed—dramatically and disastrously. Yet it would also prove disastrous for Mexico. Long before the expedition reached Mexico City, news of the men’s capture raced across Texas and the nation. Newspapers from New York to Atlanta published regular updates.

Meanwhile, Lamar had to answer to his own republic. He tried to justify his actions in a message to Texas’ Congress on Nov. 3, 1841, writing that he believed the expedition “would do more towards reviving the drooping energies of the nation, enriching the people and relieving the government from its embarrassments, than all the financial theories and speculations which may be devised for a quarter of a century to come.”

Congress wasn’t mollified, however. That December 6, with Sam Houston already in Austin to be sworn in for his second term as president, a committee recommended the House of Representatives consider articles of impeachment against Lamar and his vice president and secretary of war, noting that Congress had authorized neither the expedition nor funding for it. “His Excellency the President, in fitting up and sending out the Santa Fe Expedition, has acted without the authority of law or the sanction of reason,” the committee wrote in a draft resolution. “The reasons assigned by the president are strange, unnatural and unsatisfactory, and…the course pursued by his Excellency meets the disapprobation of Congress.”

Congress didn’t act on the recommendation, however, and Lamar retired to Richmond, Texas (though he fought with the U.S. Army during the subsequent Mexican War). Until his death at age 61 in 1859 he traveled, wrote poetry, remarried and campaigned in support of slavery.

The United States annexed Texas on Dec. 29, 1845, ending Lamar’s dream of empire. By then national opinion had turned strongly against Mexico, and shortly after Texas joined the Union, the United States declared war. Its victory stripped Mexico not only of Texas, but also of New Mexico and California. Yet Texas kept most of what it had already claimed, extending its boundaries far beyond its frontier and establishing the familiar outline it maintains today.

For further reading on this topic author Damond Benningfield recommends Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, by George W. Kendall; The Texan–Santa Fe Pioneers, by Noel M. Loomis; and Journals of the Sixth Congress of the Republic of Texas, 1841–1842.