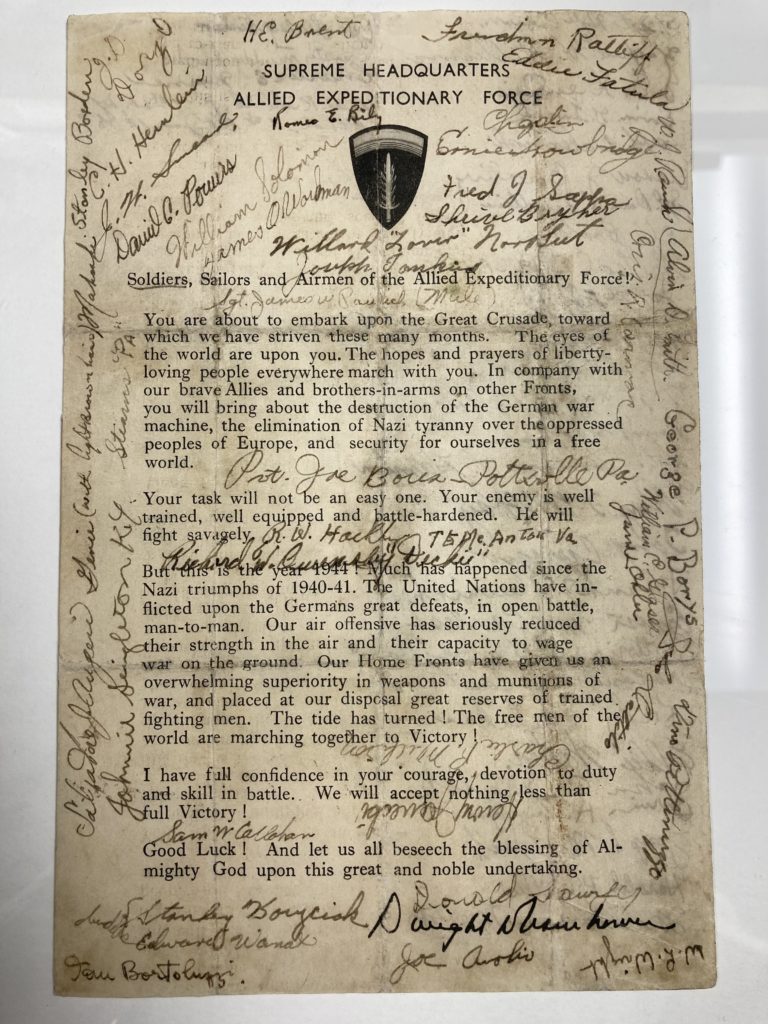

At the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Virginia, these artifacts from the beaches of Normandy are called “Silent Witnesses.”

IF A PICTURE is worth a thousand words, then some objects, when seen in person, must be worth a million.

Historic artifacts convey stories in ways that capture the imagination and bring home the reality of a moment in time. To read about an important event can be informative. To hear a description of it can be illuminating. But to view a tangible object that was there, something that survived battle to become a cherished reminder—that can be inspiring.

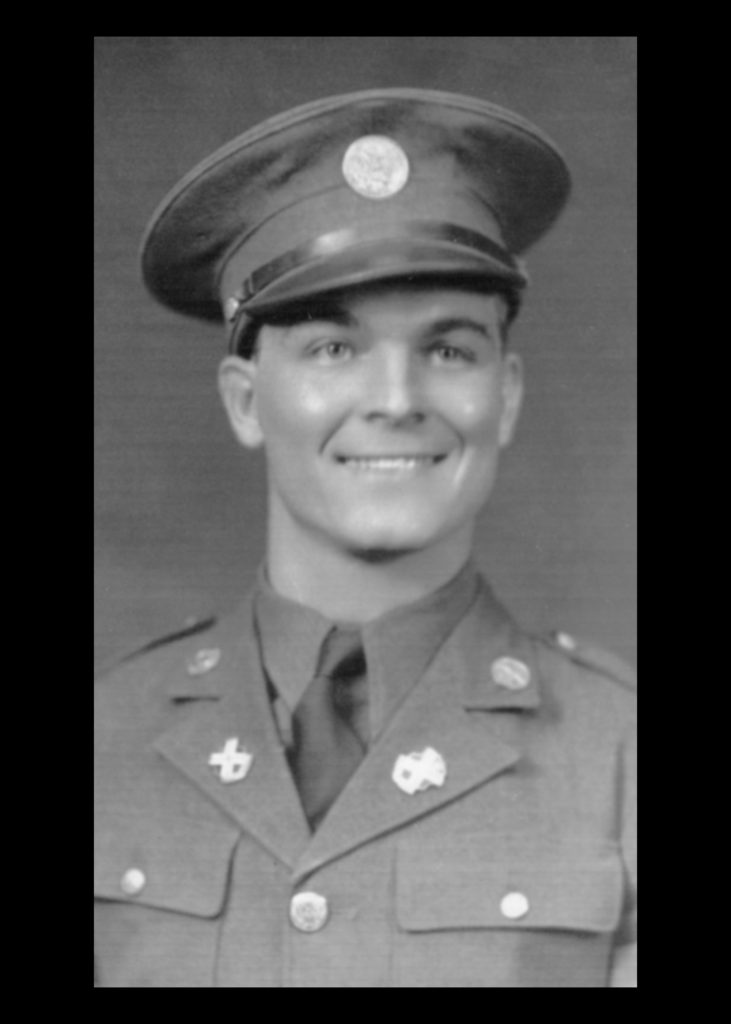

At the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Virginia, we often call such items “Silent Witnesses.” Among our broad array of World War II artifacts, some pieces hold special significance because they were at hand on June 6, 1944, on the beaches of Normandy during Operation Overlord. Carried by a soldier, held by a sailor, cradled by a comrade bringing comfort to a dying buddy—these relics from one of history’s most crucial days speak to anyone who sees them.

As time passes, fewer and fewer survivors remain to share their stories directly. Too soon, only the Silent Witnesses will be left to remind us of the tragedy and triumph that was D-Day. On these pages is a selection of these special items from the Memorial’s collection. Each one tells a tale, and together, they form a larger narrative: one of costly victory. The Silent Witnesses attest to the valor, fidelity, and sacrifice of a generation that, by winning some French beaches in a terrifying 24 hours, saved the world. ✯

—John D. Long is the National D-Day Memorial’s director of education

All photos courtesy of John D. Long/National D-Day Memorial

This article was published in the June 2021 issue of World War II.