EVERY DAY, scores of midshipmen walk down the 7th Wing corridor at the U.S. Naval Academy’s sprawling Bancroft Hall dormitory. As they pass Room 7046, they might notice a plaque on the wall commemorating one of their own, Commander Howard Walter Gilmore, class of 1926. He was a World War II submariner, a Medal of Honor recipient, and the man responsible for one of the navy’s most memorable rallying cries. After his sub, the USS Growler, was severely damaged in a February 1943 collision with a Japanese ship, Gilmore, the lone man alive on the bridge, made the choice to save his ship and crew, knowing full well he would not survive.

“Take her down!” he shouted below. “Take her down!”

By then, Gilmore had been in combat for eight months and had repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to aggressively take risks to accomplish his goal of sinking enemy ships. He died in the prosecution of that goal. But he showed how successful taking risks could be in the fight against the enemy. In the early part of the war, not every sub captain “got it.”

UNCOMMON MEN

By mid-June 1942 it became apparent to sub force commanders that men like Gilmore were rare commodities. There were too many submarine skippers who, having served their whole careers in peacetime, didn’t know how to fight a war. These men, typically in their forties, had spent the interwar period at cushy billets like Pearl Harbor or Manila. When they went on exercises, their subs were assigned as units of the fleet, to be employed for advanced scouting. These skippers won their accolades for smart, synchronous maneuvering and fast, accurate flag signaling. Independence was frowned upon. And god forbid someone should take risks. So when war came on December 7, 1941, many risk-averse submarine commanders were unable to rise to the challenge.

As submarine service historian and former navy man Clay Blair Jr. noted in his book Silent Victory: “During the first year and a half of the war, dozens had to be relived for ‘lack of aggressiveness.’” Blair chalked it up to “overcaution” on the part of skippers whose prewar training emphasized “bringing the boat back” over offensive operations. To fill the slots, “brash devil-may-care younger officers” were handed command. Their ranks included a veteran submariner, Howard Gilmore, then 39, who proved more than capable of throwing caution and precedent to the wind to show that assertive (but smart) tactics against the Japanese brought results.

from annapolis to the aleutians

AN ALABAMIAN BY BIRTH, Gilmore was raised in Meridian, Mississippi, where his father owned Gilmore Tailor & Shirt Shop, providing custom-made men’s clothing to residents of the small but growing city. After graduating from high school in 1920, Gilmore enlisted in the U.S. Navy, earning a yeoman’s rating. In 1922 he sought an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy through a tough examination the secretary of the navy gave annually to serving sailors. He succeeded and joined the class of 1926 that September.

At the Academy, Gilmore excelled in academics, but, unlike most of his fellow midshipmen, he shied away from athletics. His only brush with organized sports was a stint as manager of an intramural soccer team. His classmates, who ribbed him about his red hair and freckles, enjoyed his company—he always had fascinating stories to tell. As a sign of their esteem, they took to calling him “Count Gil.” That may have been because of his “unruffled disposition and complacent ways,” recalled one. In June 1926 Gilmore graduated 34th in a class of 436. He joined the battleship USS Mississippi as a junior officer, where he spent four years in the gunnery department.

Surface ships were okay, but in 1931 Gilmore decided to shake up his career a bit and asked for a transfer to the submarine school at New London, Connecticut. He aced the seven-month course and, in July of that year, joined the USS S-48—at the time one of the most modern submarines in the fleet. After nine months at sea, the navy sent him back to Annapolis for postgraduate studies in ordnance; in his spare time he took up competitive shooting, winning distinction as an above-average marksman with both rifles and pistols. A stint at the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, D.C., followed, where he helped supervise the manufacture of cannon of various calibers. In October 1935, after two years of shore duty, Gilmore was rotated back to sea and subs, eventually becoming CO of his own sub—the old S-48—in April 1941.

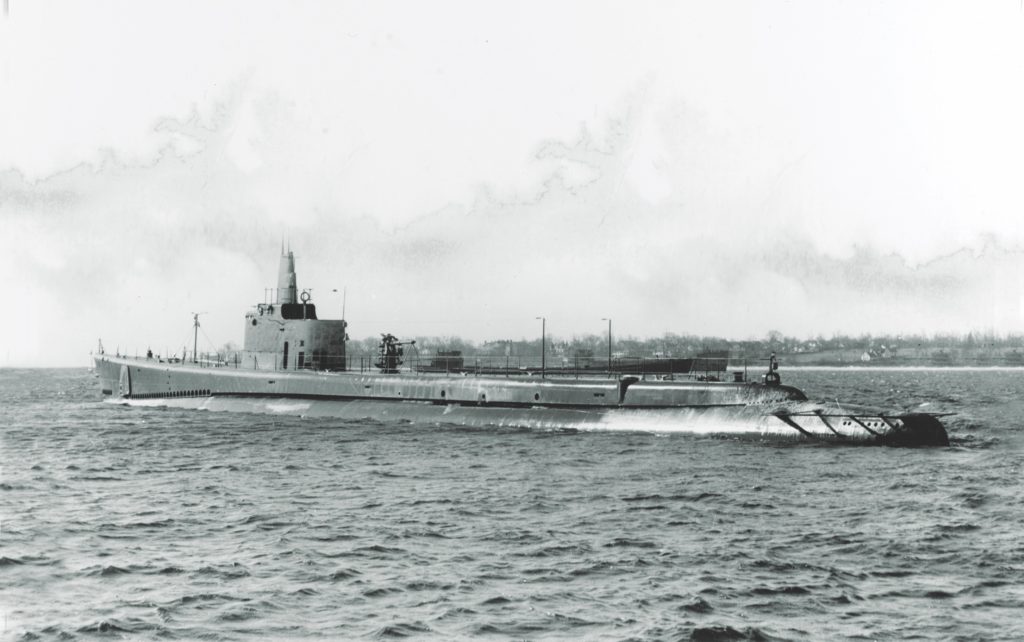

The day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Gilmore was assigned to command the USS Growler, still under construction at Groton, Connecticut. Lieutenant Arnold F. Schade was named his executive officer. Their mission was to see the boat finished, put it into commission, hone a cohesive fighting crew, and take the sub to war. The 311-foot, 1,500-ton Gato-class boat was the culmination of a decade of effort to ensure the navy had a modern, long-legged submarine capable of working independently in Pacific waters. It carried 24 torpedoes, had a top surface speed of 21 knots, and a range of 11,000 nautical miles.

Growler officially joined the navy in March 1942 and, on June 9, reached the submarine base at Pearl Harbor. Each day en route, Gilmore drilled his crew hard in diving, gunnery, and torpedo-firing exercises. After a week at Pearl, the boat departed for Midway, an atoll nearly 1,000 miles to the west. But when Commander Gilmore arrived at the navy base there on June 24, he found his mission had changed. Instead of heading on to the Western Pacific—where all the action was said to be—Growler was redirected toward the Aleutian Islands, 2,500 miles to the north, to observe Japanese operations in the wake of enemy landings on Attu and Kiska earlier that month. The invasion had been meant to draw U.S. forces away from the Midway area and the great battle fought there the first week of June, but it also served to rattle the fragile psyche of the American public by demonstrating that Japan had the ability to attack and occupy American soil.

On the morning of June 30, snow-covered Kiska Volcano came into view to lookouts on the Growler, rising above the mists surrounding the island. The sub spent the next few days patrolling the coastline, reporting ship and aircraft contacts back to headquarters at Pearl. On July 5 they spotted three Japanese warships anchored close together in Reynard Cove. The cove—about halfway up the mountainous east coast of Kiska—had been the site of one of the Japanese landings on June 7. Gilmore identified the vessels as 2,000-ton destroyers. It was a perfect setup: like three ducks in a row.

He assessed the risks and decided to attack all three at once. It would be the first shot of his war and he wanted to make the most of it. The captain rang “general quarters” and, at 5:55 a.m., fired four torpedoes. Two hit their targets amidships. Another exploded under the foremast of the third—a good start. But Gilmore hadn’t reckoned on an anchored destroyer shooting back. One of them fired two torpedoes from its deck tubes toward the American submarine. Running “hot, straight and normal,” they “swished down each side of Growler,” the skipper wrote in his report about the close call. A few feet closer on either side, and the sub would have been at the bottom of the bay. The incident thoroughly spooked the crew, who could hear the missiles zinging past the hull. Japanese planes and a patrol boat pressed home their attack on the sub, peppering the sea with bombs and depth charges, and knocking out Growler’s supersonic sonar and one of the periscopes. Gilmore headed for deep water and kept the sub under for five and a half hours until it was clear of the chaos.

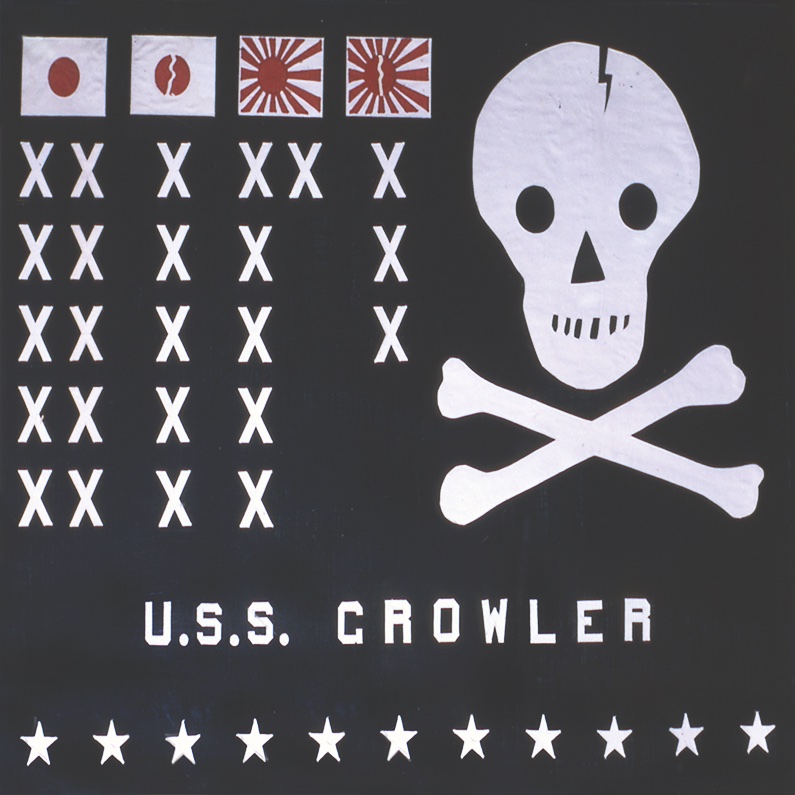

Its basic mission completed, Growler headed back for Pearl, arriving on July 17, 1942. The commander of the navy’s submarine force in the Pacific, Rear Admiral Robert H. English, opened his written assessment with considerable approval for Howard Gilmore’s performance: “The first war patrol of the GROWLER was extremely well conducted and the results were most gratifying. The attacks on the three destroyers merit the highest praise.” For the Aleutian action, Gilmore was awarded his first Navy Cross, the service’s second-highest honor. Clay Blair called him “a remarkable officer, who seemed to be without fear.”

running out of luck

GROWLER’S SECOND war patrol proved even more fruitful than the first, though it got off to a slow start. Patrolling off Formosa (now Taiwan) in late August 1942, the boat made two attacks on enemy freighters in the first three days. Both failed, and Gilmore chastised himself for being overanxious and going after targets under marginal conditions. The strike on the second ship had led to a three-hour reprisal by Japanese antisubmarine forces.

Just before 5 a.m. on August 25, Growler was running submerged when the skipper ordered “up periscope” to take a quick look around. He was astonished to find that he had sailed into the midst of a flotilla of nearly 150 fishing boats, which were “near us for the next three hours.” Early that afternoon he spotted the Senyo Maru, a 3,000-ton freighter. It took four torpedoes to sink the hapless merchantman. Then came the usual furious counterattack from air and sea. The pressure on the crew was tremendous. One sailor had a panic attack at his station and had to be sedated with morphine.

Six days later, on August 31, Gilmore sank the 5,800-ton freighter Eifuku Maru with two torpedoes. In the early hours of September 4, he unlimbered Growler’s 3-inch deck gun and gave his gun crew a chance to down a sampan that had been trailing the sub. It took them just six rounds. Later that same day he attacked the 10,000-ton Kashino. The captain identified the ship as a large tanker, but in fact it was a vessel specially designed to transport the massive 18.1-inch guns for the super-battleship Yamato from the gun factory to the shipyard at Kure. Each barrel was 70 feet long and weighed 145 tons. He expended four torpedoes on Kashino and was pleased when the big freighter sank in two minutes.

Growler’s final victory of the patrol came on September 7 with the sinking of a small freighter, Taika Maru. Gilmore headed to Midway on September 23, sailing into the sub base there with all 24 of his torpedoes expended. Admiral English poured more accolades upon the commander’s performance, writing that “all attacks were aggressively prosecuted.” The commander was awarded a second Navy Cross, in the form of a gold star. His combat record in the first eight months of the war put him in the ranks of what were at that time the submarine force’s most successful skippers.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

On October 22, 1942, Growler departed Midway heading southwest. Gilmore’s mission on this third war patrol was to scout what naval intelligence said was a busy enemy shipping lane along New Britain Island leading to the Japanese fortress at Rabaul. The U.S. Navy could read Japanese naval codes, including the primary one, “JN-25,” that told them precisely where a given convoy, or even a single ship, might be at a given day and time. It was not an infallible system: a communications snafu on November 17 sent Growler to the wrong location to intercept a convoy of cargo ships headed south, and Gilmore found nothing. Late on November 20 the navy sent another cable directing Growler to a spot near the northern end of the island to interdict three groups of enemy warships inbound for Rabaul. But he again found nothing, and lost another opportunity to attack.

On November 25 Growler made the patrol’s first real enemy contact. Gilmore identified the ship as a destroyer. But it was moving too fast, so he abandoned his effort. The next day he spotted a big freighter at 16,000 yards and began preparing for an attack, but his target started zigzagging wildly, so he had to let it go once again. Time and again the sub was ready to pounce but the conditions never seemed propitious. “Approaches were attempted on every vessel sighted. No attack possible,” he wrote. On December 4, the navy pulled the plug, and Growler was ordered to sail to its new home base at Brisbane, Australia. Thirty-one days on station and, despite the JN-25 decrypts, the boat had sighted just eight Japanese ships and returned with all 24 torpedoes unfired. There would be no praise for this patrol.

FINAL VOYAGE

THE SUB’S FOURTH PATROL began on New Year’s Day 1943 with orders to return to New Britain to again search for Japanese shipping. On January 16 radar picked up a convoy of eight freighters with three escorts. It was just the sort of target Howard Gilmore relished. He reckoned the risks were manageable, so at 8:45 a.m. he started his approach. Though the ships were making frequent course zigzags, just after 10 o’clock the enemy zigged directly into the path of Growler. The skipper fired two torpedoes that hit the 5,900-ton passenger and cargo ship Chifuku Maru. Down it went.

Watching through the periscope Gilmore spotted a destroyer just 400 yards out charging toward his submarine. “Dive! Dive!” he ordered as the klaxon rang throughout the boat. Depth charges from the destroyer rained down on Growler, some pretty close, but the skipper again managed to evade his attackers and continue the patrol. On January 30, just before 7 p.m., he fired four torpedoes at the 6,400-ton Toko Maru. One hit and blew off the vessel’s bow. After the desultory third patrol, things were looking up on the fourth.

An hour after midnight on Sunday, February 7, Growler was patrolling on the surface off the southwest coast of the Solomon Islands. At 1:10 a.m., radar picked up a blip at a range of 2,000 yards. Moments later, despite miserable visibility, the boat’s four lookouts spotted the ship on the horizon. Haze intermittently blocked their view, but they could tell that what appeared to be a small gunboat was moving away from the submarine. Commander Gilmore decided to give chase.

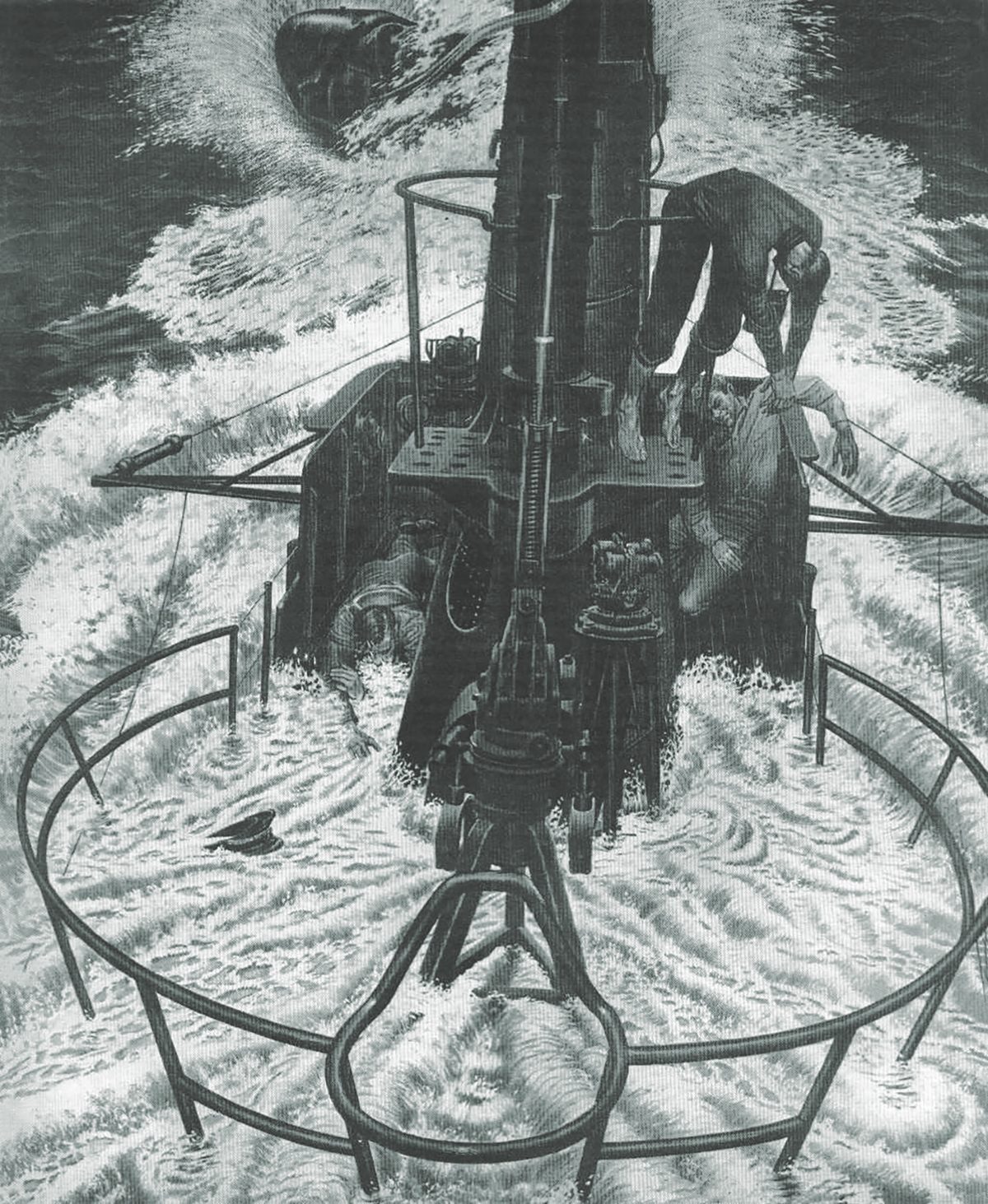

He immediately went into attack mode, made all tubes ready, and joined his men on the narrow, open-air bridge at the front of the conning tower. Growler bore down on the target, slowly closing the gap. But through the dense haze, no one in his crew noticed that the enemy ship had apparently spotted the sub, reversed course, and was heading straight toward it at 15 knots. The adversaries were on a collision course, with the distance between them diminishing rapidly. The men operating the torpedo data computer in the conning tower—a sophisticated analog device that kept track of range, speed, and course—announced they had locked onto the target. Seconds later, executive officer Arnold Schade called up to the bridge: “We’re too close!” By that he meant that the exploders on the sub’s Mark XIV torpedoes required a run of at least 500 yards to arm and the converging ships were now closer than that. It was too late…too late for Howard Gilmore to avoid the inevitable. When he realized the hopelessness of his predicament, he ordered “left full rudder” and sounded the collision alarm.

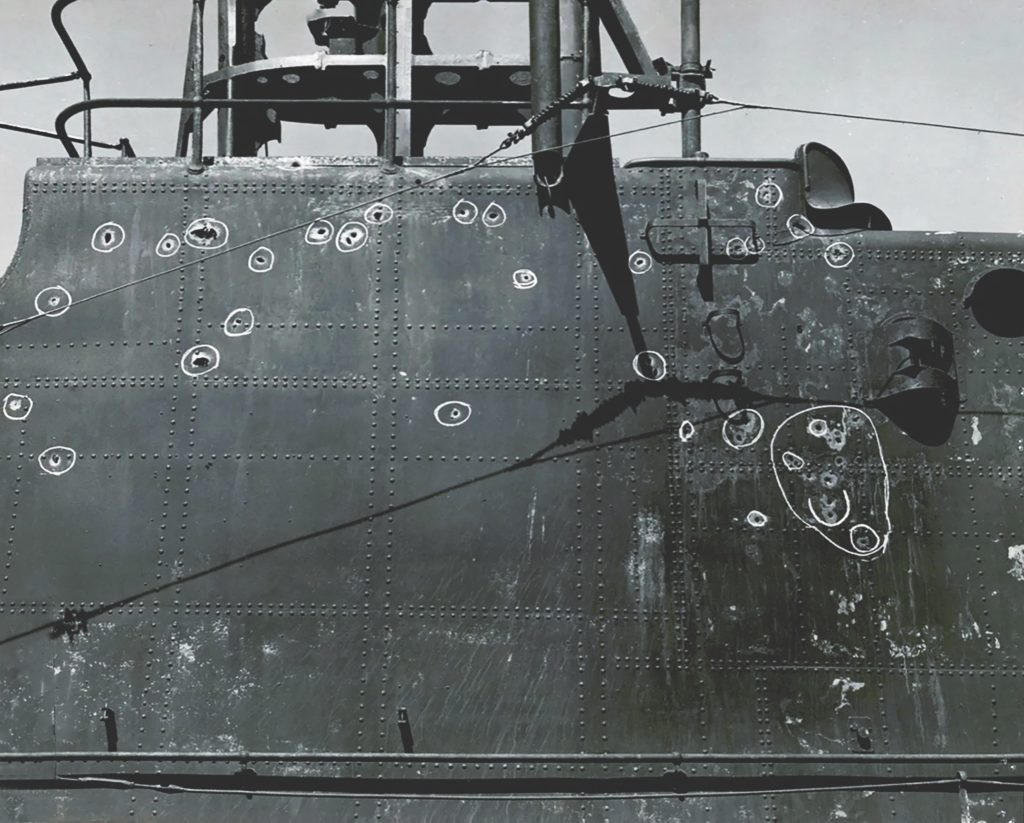

At 1:35 a.m. Growler smashed into the port side of what turned out to be the Hayasaki, acombat support vessel, at 17 knots, bending 15 feet of its own bow back nearly 90 degrees to port, crumpling the first 35 feet of the hull, disabling the forward diving planes and forward torpedo tubes, and making a huge hole in the enemy boat’s side. The sub rolled 50 degrees before slowly righting itself. The impact knocked everyone aboard the submarine to the deck and killed most of the boat’s electrical systems. Water poured in through numerous leaks—the pump room flooded to a depth of several feet. Things looked grim for Growler.

Multiple machine guns aboard the enemy ship began raking the conning tower, peppering the thin steel plate with .50-caliber bullets and striking all six men on the bridge, Gilmore included. “Clear the bridge!” the wounded captain shouted, ordering everyone to get below—but only three men made it. Two others, Ensign William W. Williams and Fireman Wilbert F. Kelley, had been killed outright in the fusillade, leaving the captain the only living soul topside. Below, Schade waited in vain for his skipper to appear at the bridge hatch. That’s when he heard Howard Gilmore give his immortal order: “Take her down! Take her down!”

Schade hesitated for a full half-minute before turning to the yeoman and ordering him to “sound the diving alarm.” Growler slowly disappeared into the depths. Though watertight hatches protected the sub, several compartments rapidly flooded, making it difficult for the crew to maintain depth control. Schade kept the boat submerged for an hour, then surfaced so the crew could search for the skipper, knowing in their hearts that they would not find him. They also checked out the damage. “The ship was just a total mess,” Schade recalled after the war. He fired off a radio message to HQ, explaining their situation and the loss of the captain and two other men. Brisbane responded with an order to terminate the patrol and have Growler get back to Australia as best it could.

SILENT NO MORE

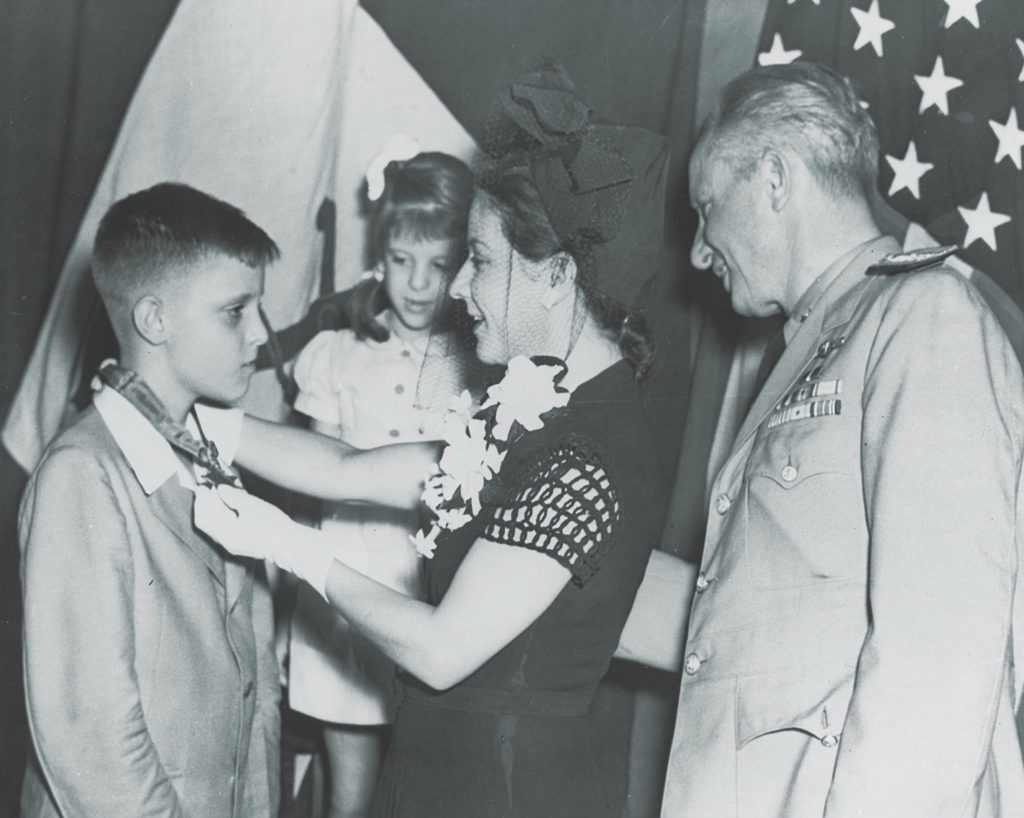

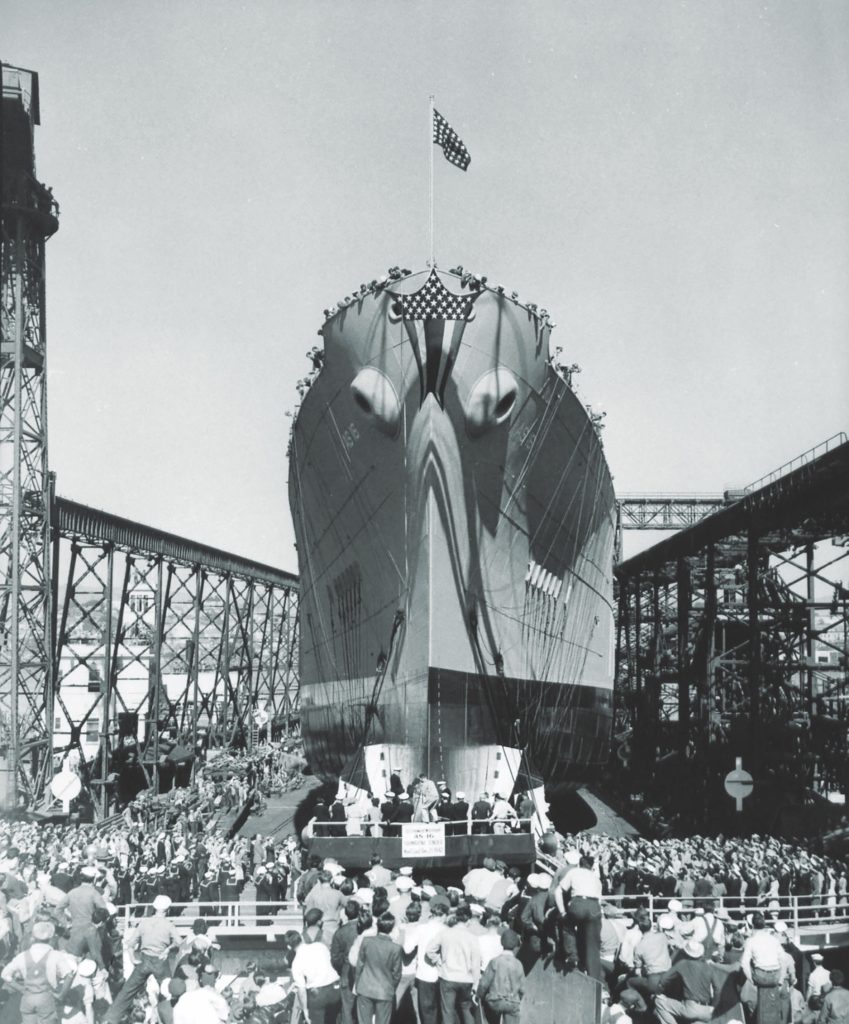

FOR THREE MONTHS, the “Silent Service” kept the story of Growler’s heroic skipper and his final order to itself. On May 7, 1943, the navy finally released an official communiqué that became front-page news across the United States. Details eventually reached chief of naval operations Admiral Ernest J. King, along with a request from the submarine force commanders that he bestow the nation’s highest honor upon Howard Walter Gilmore—the Medal of Honor. Gilmore would become the first submariner to receive the medal in World War II—to be joined by six others over the course of the war. In a ceremony in New Orleans on July 13, 1943, Rear Admiral Andrew C. Bennett, commandant of the Eighth Naval District, placed the medal around the neck of Gilmore’s wife, Jeanne, as their children, Howard Jr. and Vernon Jeanne, looked on. That September, Jeanne sponsored the launch of a new submarine tender, the USS Howard W. Gilmore, which served with distinction in the Pacific Theater.

Growler had limped into the base at Brisbane on February 17 after a Herculean effort by the ship’s crew to restore it to a semblance of operability. The big question was whether the ship’s bow was repairable and whether it could be done in Australia. After surveying the damage, U.S. Navy engineers concluded that a new nose could be fabricated at Brisbane; the work was completed in early May, around the time Gilmore’s story went public. As a final, whimsical touch the Australians welded nickel-plated kangaroo cutouts to each side of the nose. On May 13, 1943, USS Growler, with Lieutenant Commander Arthur F. Schade as its captain, steamed out on its fifth war patrol. Schade remained with the sub through its eighth patrol.

Over the course of the war Growler racked up an impressive score of 15 Japanese ships sunk and 7 damaged. The boat’s luck finally ran out on November 8, 1944, during its 11th war patrol, when it was sunk by a Japanese destroyer southwest of Manila Bay. There were no survivors.

But Gilmore’s courageous order took on a life of its own, joining proud U.S. Navy slogans like “Don’t give up the ship,” “I have not yet begun to fight,” and “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.” Any midshipman pausing outside Bancroft Hall’s Room 7046 can read the words of Gilmore’s Medal of Honor citation: “For distinguished gallantry and valor above and beyond the call of duty.” In the armed forces of the United States, there is no higher calling. ✯