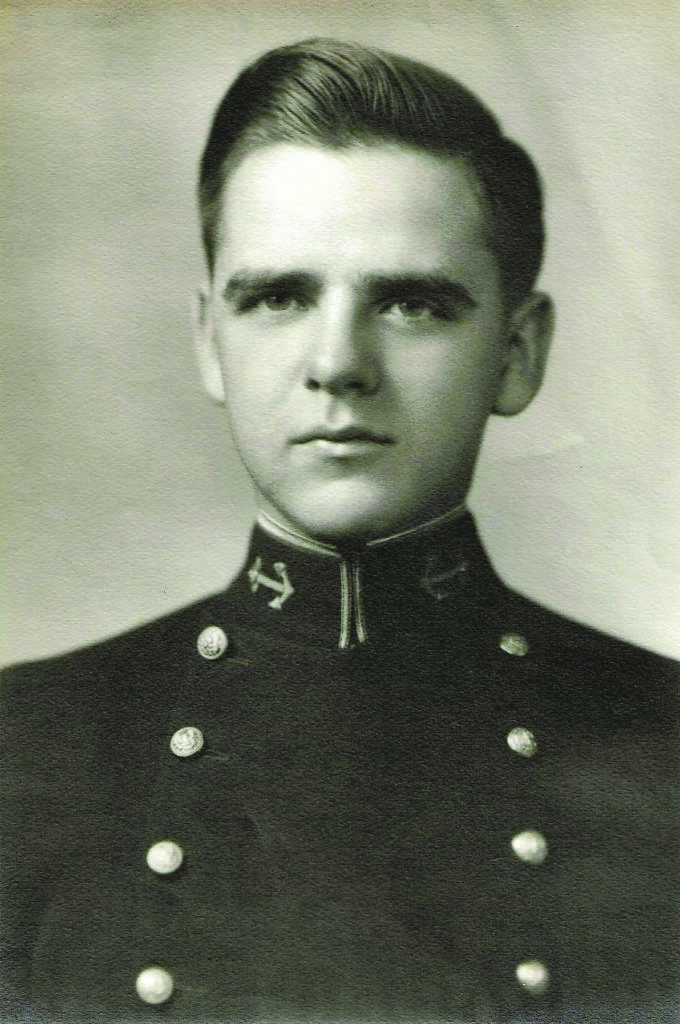

Archie Parmelee Kelley was fresh out of naval training at 23 years old and aboard the USS West Virginia on the morning of December 7, 1941, when Japanese torpedoes began slamming into the battleship, shaking it violently with each strike. As torpedo after torpedo hit—seven in all, along with two bombs—Ensign Kelley rushed to close the watertight doors below deck, where water was flooding in, and to counterflood the ship to prevent it from capsizing—a quick action that may have saved hundreds of lives. But it also required a move that cost other lives. At 101 years old, he’s long since reconciled with that decision—though the events of that morning are never far from his mind.

What made you want to join the navy?

My father was an admiral in the navy. I felt the family obligation to be in the navy, and it was more than just wanting to join. I knew I wanted to follow him and went into the Naval Academy. At my entrance physical, the doctor examining me said I couldn’t get in because I didn’t have a uvula; when I was 13, a navy doctor had accidentally removed it during a tonsillectomy. I immediately said, “But a navy doctor removed it!” So the doctor came back and decided I was qualified after all [laughs].

After the Naval Academy, where were you assigned?

I graduated early due to the war looming. I was young and excited to get assigned to the battleship West Virginia in Hawaii. My future bride lived ashore on the islands at the time. We really enjoyed our times surfing, and dancing onshore and on the boat. On December 7, this all changed.

You were on the battleship when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

I was sleeping when the first missile hit the ship. I was the assistant damage control officer, but my boss was ashore, so I was responsible for the ship. I had no experience then, except for in books. And no shoes on. The ship would shake so violently during each torpedo strike that no one could stand up. I ran to my battle station, which was the central station compartment, low in the ship. That was where the captain and all his chiefs of staff were to assemble. The reason we chose central station was because it was the safest compartment in the ship. It’s also the last compartment to be flooded if a ship was sunk. And that room began to flood.

What then?

There was water above me on the top deck. The ship had sunk to the bottom of the harbor already, which was only 20 feet down. That wasn’t important; what was most important was keeping the ship from rolling over. When the USS Oklahoma, which was in front of us, sank and rolled over, 400 people died. Water was coming in through the doors and the ceilings of the compartment. I had to make the decisions and started to close all the watertight doors.

One decision was especially tough.

We had to keep a door shut to keep more water and fuel from flooding into the room. I could hear three or four men screaming on the other side of the door. But I had to keep it shut; if I opened it, the central station compartment would flood. It was an obvious decision to make as an officer. But it was a terrible feeling that you were killing some of your shipmates right then and there by keeping this door shut.

How do you reckon with that decision now, so many years later?

There were 40 people on our side of the door, so nobody questioned the decision to keep that door shut. These are the decisions that have to be made in combat and action. What would have been a lousy decision and one that would have been challenged the rest of my career would be if there had been a few officers on my side and 40 men on the other.

You were also integral to keeping the ship upright. How did you do that?

Navy ships are designed to easily flood compartments by opening certain valves. All of us in the compartment knew it would be a few hours before our compartment flooded to the point where we would be killed. While it was flooding, we stayed in and helped counterflood compartments on the side that wasn’t hit by torpedoes, to keep the ship upright. While we were doing that, the water reached up to just under our noses. I wasn’t sure how we would get out since the deck was flooded above us. But eventually, I had to basically say “abandon ship” to leave the compartment.

There was one very narrow ladder on a wall, in a tube that went above the upper deck so the officers manning the upper deck could climb down to this safer space when the ship was being attacked. That tube led to the conning tower. Nobody knew what was going on topside—if it was worth going. We had the men climb up this ladder to the upper decks. The ladder was small, just a small steel cylindrical thing in the wall. It was fairly slow going, and we had to climb about 60 or 80 feet. Everybody in the compartment was saved.

What happened when you reached the top of the battleship?

At the top, you were in good shape. We saw the water, and it was easy to swim to Ford Island.

I dove into the water and was picked up by a boat. When I reached the shore I was in shock.

You went on to serve in the Pacific as a gunnery officer aboard the destroyer USS Gansevoort, and after the war studied nuclear physics at MIT. Why the change?

My wife was in San Diego, and my being at sea for two or three years affected all of us. I was anxious to get a shore job, so I applied for MIT. That’s how I got out of the navy fleet: by applying to MIT [laughs]. I wanted to go ashore, and the navy wanted me to study business administration, and I said: “No, I don’t want to do that; I want to do something highly technical [laughs].” It salvaged my marriage and turned out to be a great thing, academically. My entire career has been based on that nuclear education and becoming one of the first nuclear engineers in the navy. ✯