Japan never seriously considered the following scenario—but might have been wise to do so.

On December 15, 1941, naval and air units of the empire of Japan suddenly and deliberately attack the Dutch naval squadron at Batavia in the Netherlands East Indies (present-day Indonesia). They destroy or damage all five cruisers and eight destroyers, leaving fifty-five-year-old Vice Adm. Conrad Emil Lambert Helfrich with only twenty submarines and numerous but frail torpedo boats with which to retaliate.

Shortly thereafter the Japanese Sixteenth Army invades the Dutch portion of the island of Borneo—scrupulously avoiding portions administered by Great Britain— then rapidly follows up with attacks on Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and other major islands in the East Indies archipelago. The puny Dutch garrisons are swiftly overrun, the Dutch naval bases at Batavia and Surabaya quickly fall, and by the end of February 1942, Japan has secured the Netherlands East Indies’ cornucopia of petroleum, natural gas, tin, manganese, copper, nickel, bauxite, and coal.

The Japanese government had taken the first step toward an attack on the East Indies in July 1941, when it demanded and received from Vichy France the right to station troops, construct airfields, and base warships in southern Indochina. The German invasion of the Soviet Union the previous month had removed any threat from that direction and cleared the way for a thrust southward. The southward move, in turn, was predicated on Japan’s desire to secure enough natural resources to become self-sufficient. It was dangerously dependent on America for scrap iron, steel, and above all oil: 80 percent of its petroleum came from the United States. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration had been attempting for years to use economic sanctions as lever age to force Japan to abandon its invasion of China. As expected, the move into southern Indochina triggered a total freeze of Japanese assets in the United States and a complete oil embargo.

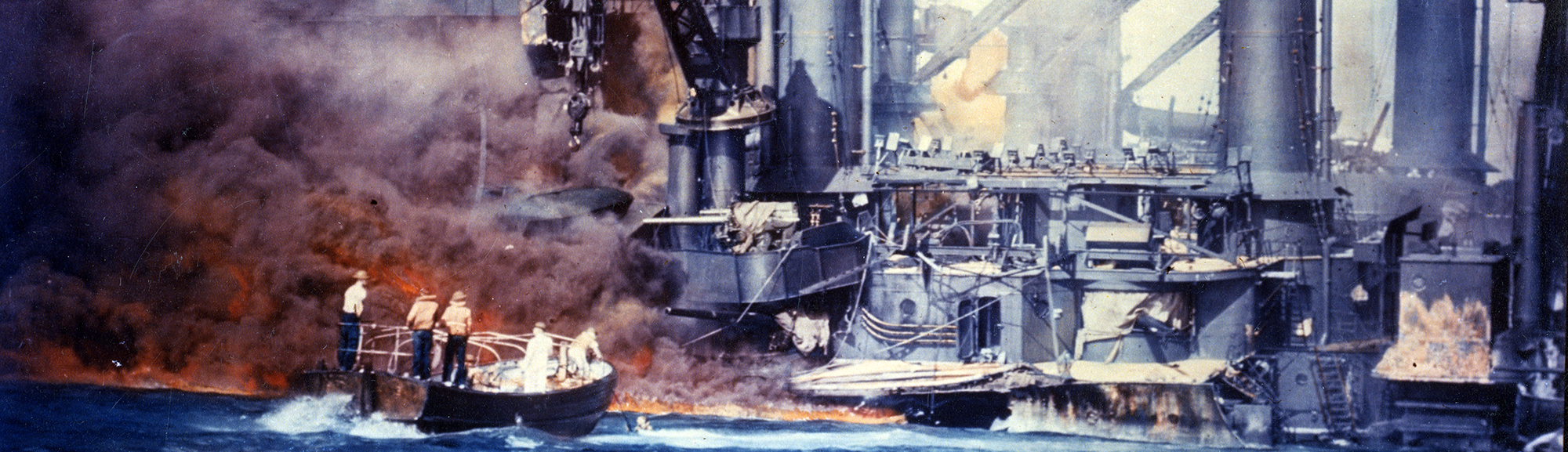

Japanese leaders initially assume that if they proceed with their intention to grab the Dutch East Indies, the inevitable con sequence will be war with both the British Commonwealth and the United States. Consequently, plans also include attacks on British bases at Singapore and Hong Kong, American bases in the Philippine Islands, and even the forward base of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Careful review of the British and American situations, however, prompts a reconsideration by Japan’s planners. They conclude that the beleaguered British cannot afford to add Japan to their existing adversaries, Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Britain especially cannot do so without a guarantee that the United States will enter a war with Japan. And although the Roosevelt administration might engage in threats, American public opinion is so averse to war that the president has been unable to persuade the country to enter the fight against the Nazis despite their conquest of most of Europe. Indeed, a July 1941 bill to extend the nation’s peacetime draft—which the Roosevelt administration deemed fundamental to U.S. national security—passed by a single vote.

The revised Japanese plan therefore contemplates an attack on the Dutch East Indies alone, albeit with most of the Imperial Japanese Navy held in reserve should either Great Britain or the United States declare war.

Events completely vindicate Japan’s gamble. British prime minister Winston Churchill reinforces Singapore but otherwise adopts a defensive posture in Southeast Asia. Already thwarted in his efforts to make the case for war against Hitler’s Germany, neither Roosevelt nor his advisers can think of a rationale persuasive enough to convince the public that American boys should fight and die because the Japanese have overrun an obscure European colony.

How plausible is this scenario? There is little doubt that Japan could have swiftly defeated the Dutch and seized the East Indies in mid December 1941. Even when (as occurred historically) the Americans, British, and Australians added their available warships to the defense of the Dutch colony, the Japanese had little trouble overrunning the entire archipelago by March 1942.

The harder question to answer definitively is what course Britain and America actually would have pursued if Japan had bypassed their Pacific possessions and also, of course, refrained from an air strike against Pearl Harbor.

The British plainly could not have sustained such a war without American help. True, Great Britain and the United States had been steadily making common cause against Nazi Germany. The U.S. Congress had passed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941, and U.S. destroyers had begun escorting convoys bound for Great Britain to the mid-Atlantic before handing them off to their British counterparts. In August, Churchill and Roosevelt had met for a secret conference in the waters off Newfoundland, a summit that had included military as well as diplomatic discussions. And by the autumn of 1941, the U.S. Navy was engaged in an undeclared but lethal war with German U-boats.

Cooperation to prepare for a conflict with Japan, however, was considerably less advanced. At the Atlantic Conference, the British had given the Americans text for a proposed warning to Japan to be sent jointly by Great Britain, the Netherlands, and the United States, stating that if Japan pursued further aggression in Southeast Asia, the three countries “would be compelled to take counter measures even though these might lead to war.” Roosevelt agreed to make such a stern statement— but unilaterally, not jointly—and as matters turned out, the president told the Japanese ambassador merely that if Japan struck southward, he would take steps “toward insuring the safety and security of the United States.”

As the crisis with Japan deepened, Roosevelt’s top military advisers told him that while they preferred a less provocative diplomatic line toward Japan, the United States could not stand by if the Japanese struck American, British, or Dutch possessions and would have no choice but to take military action in that case. Privately Roosevelt agreed, and on December 1 he told the British ambassador that in the event Japan attacked the Dutch East Indies or British possessions in Southeast Asia, “we should all be in this together.” When the ambassador pressed him to be specific, Roosevelt replied that the British could count on “armed support” from the United States.

But the president also worried about his ability to do so if American possessions continued to be spared by the Japanese. As historian David Reynolds points out, “Roosevelt could only propose war; Congress had to declare it. From a purely diplomatic point of view, Pearl Harbor was therefore a godsend.” It would have been difficult to persuade Congress that an attack upon the Dutch East Indies alone demanded a military response; it might well have proved impossible.

In the end the dilemma never arose because the Japanese never considered such an alternative strategy. Once the Japanese government decided that it must seize the natural resources of the Dutch East Indies, it never seriously considered any plan but a simultaneous attack against the British and the United States in the Pacific. This decision was driven overwhelmingly by operational considerations: Japan’s military planners believed they could not run the risk of leaving the American air and naval bases in the Philippines athwart their line of communications with the East Indies. For that reason they concluded the Philippines must be captured as well.

Ironically, by refusing to run such an operational risk, they wound up taking an even larger strategic risk, for the attack on Pearl Harbor was premised on the highly tenuous assumption of a short war with the United States followed by a negotiated peace that would allow Japan to keep its territorial gains. Japan bet that American public opinion would never countenance a prolonged and bloody Pacific war and that the combination of the blow to the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor and Japan’s erection of a hermetic defensive perimeter in the Central and South Pacific would convince America to throw in the towel.

As actual events subsequently showed, that was a poor bet.

Originally published in the September 2007 issue of World War II Magazine. To subscribe, click here.