On January 6, 2021, President Donald Trump capped a months-long campaign against the legitimacy of the election in which he lost the presidency with an incendiary speech to 2,000 supporters on the Ellipse outside the White House. After the rally, several hundred in the crowd marched up Pennsylvania Avenue to the U.S. Capitol, where Congress was certifying the states’ electoral votes. The crowd swarmed the building, smashing doors and windows, battling cops, and taking copious selfies. One rioter and one cop were killed, three rioters died from medical emergencies. The most appropriate tweet of the day, from a citizen horrified by media coverage of the mayhem: Can we have 2020 back?

What Americans have gotten back instead is 1899’s Kentucky gubernatorial election, and its deadly aftermath.

A slave state that had stayed in the Union, post-bellum Kentucky was a tinderbox. Its political class mixed ex-Confederate Democrats, Republicans, and Populists. Squeaker elections—in 1896 William McKinley carried the state by fewer than 300 votes—stoked partisan passions. Kentuckians were a trigger-happy lot, as apt to settle grievances via duels and feuds as lawsuits; the McCoys of the state’s eastern mountains battled the Hatfields of West Virginia for decades.

A rising figure in this maelstrom as the century ended was Covington lawyer William Goebel. A son of German immigrants, Goebel was not an obvious politician, much less a lightning rod. Cold and silent, he put one journalist in mind of a reptile. But Goebel was smart, hard-working, and ambitious, and early on he adopted a populist cause: regulating the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. That line, the state’s largest, could break small farmers with its freight rates. Its lobbyists ruled Frankfort, the state capital. In 1887 voters sent Goebel to the General Assembly as a Democratic state senator.

Goebel displayed his mettle clashing with John Sanford. The politically connected Covington banker had blocked Goebel from getting a judgeship he coveted. Goebel published an anonymous newspaper essay calling Sanford “Gonorrhea John.” He coyly blocked out a few letters easily imagined by even the dullest reader. In April 1895, the two met on a Covington street. “I understand you assume the authorship of that article,” said Sanford. “I do,” answered Goebel. The antagonists drew pistols and fired, almost simultaneously. Sanford’s bullet passed through Goebel’s coat and trousers; Goebel’s struck Sanford’s forehead, killing him. Goebel coolly turned himself in to the chief of police. Since witnesses could not say who fired first, Goebel successfully pleaded self-defense, beating both a criminal rap and a civil suit filed by Sanford’s widow.

Goebel prepared for his next step, the 1899 governor’s race, by adding issues to his quiver: Republican corruption (the GOP held the statehouse), prison reform, and a modest dose of female suffrage, proposing to allow women to vote in school board elections. Most important, in 1898 Goebel pushed the assembly to create a State Board of Election Commissioners. Under existing rules, each county conducted its own vote and certified its own returns. Democratic counties regularly threw out Republican ballots, while Republican counties returned the favor—a crooked system whose gimcrack stasis maintained an ad hoc balance of power. Goebel’s State Board, by contrast, would itself select each county’s vote counters while answering to the party controlling the General Assembly—which happened to be Goebel’s Democrats. Despite charges of bossism and machine politics, Goebel got his way, and filled the Board’s three slots with supporters.

Upon winning the Democratic nod for governor in June 1899, Goebel stumped the state with William Jennings Bryan, the national party’s silver-tongued star. Since Republican Governor William O’Connell was term-limited, the GOP put up William Taylor, a mustachioed Morgantown lawyer. In November, Taylor seemed to have won, 193,714 to 191,331.

All eyes turned to Goebel’s handpicked State Board. Surely the commissioners would invalidate enough Republican votes to give Goebel the statehouse.

Lame-duck Governor O’Connell asked President McKinley to order 1,000 federal troops into Kentucky to maintain order—that is, to protect Taylor’s lead. McKinley declined to involve the federal government.

Republicans from around eastern Kentucky took matters into their own hands, flocking to Frankfort, armed. A Louisville editor, coining a potent phrase, called on good citizens to “stop the steal.”

On December 9, the State Board surprised all parties by declining to invalidate any of the results, on grounds that it lacked authority to investigate charges of fraud. Taylor was inaugurated on December 12.

Goebel and the Democrat-dominated General Assembly, however, held a hole card. When the new session of the legislature opened on January 2, Goebel, acting as leader of the state Senate, charged that the votes from no less than 50 counties had been tainted. A committee of 11 solons was chosen by lot to review his claims; mysteriously, the lot-drawers picked nine Democrats, one pro-Democrat Populist, and only one Republican.

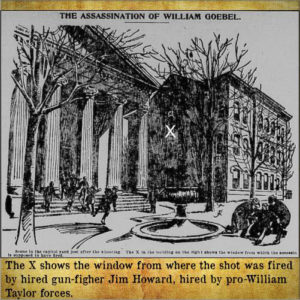

Angry, armed Republicans continued to swarm Frankfort as the committee deliberated over the results. The explosion came on January 30. As Goebel was walking to the statehouse: five or six shots were fired from a state office building, one catching him in the chest. Governor Taylor called out the militia and summoned the legislature into a special session in London, a Republican stronghold in southern Kentucky. But the majority Democrats, meeting in a Frankfort hotel, accepted the committee’s judgment that Goebel had in fact won. Sworn in January 31, the wounded man died three days later. Controversy shrouded even his last words. Admirers recalled a stirring envoi: “Tell my friends to be brave, fearless, and loyal to the common people.”

A skeptical journalist reported the dying man’s comment on his last meal: “Doc, that was a damned bad oyster.”

Under Kentucky law, the lieutenant governor opened legislative sessions. Two men now were laying claim to that slot: Goebel’s running mate, J.C.W. Beckham, and Taylor’s, John Marshall. Beckham sued Taylor and Marshall, who countersued, and their consolidated case went up to the U.S. Supreme Court, Taylor and Marshall losing all the way.

Taylor had other legal issues crowding his plate: accused of plotting his opponent’s assassination, he fled across the Ohio River to Indiana, where the Republican governor refused to extradite him. Jurors convicted a lesser Republican official and a notorious gunman from one of Kentucky’s feud-wracked counties of the shooting. The next Republican to win the Kentucky governorship eventually pardoned them and Taylor.

Kentucky’s culture of violence contributed to the state’s poisonous political climate. But for too long Kentuckians had been shooting off their mouths as well as their guns. “Gonorrhea John” was only one epithet among many barked by members of a crowd that painted opponents in the most lurid colors, expecting nothing good from them and fearing every possible dirty trick. Every election became a last stand; any loss could be final.

The day after Goebel died, Ambrose Bierce, satirist par excellence, wrote in William Randolph Hearst’s flagship New York newspaper:

The bullet that pierced Goebel’s breast

Can not be found in all the West;

Good reason, it is speeding here

To stretch McKinley on his bier.

In September 1901, President McKinley was in Buffalo, New York, gladhanding at an exhibition when an unemployed factory worker shot him. Leon Czolgosz’s reading ran to anarchists rather than Ambrose Bierce. His bullet was lethal all the same.

Mean what you say but say only what you mean.

This Déjà Vu column appeared in the April 2021 issue of American History.