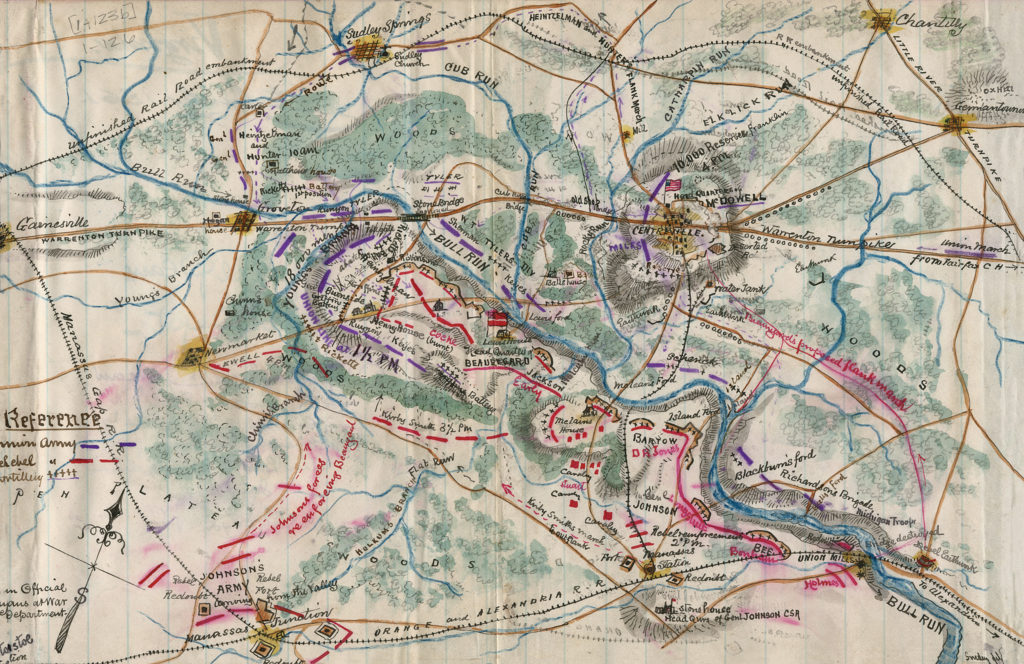

It was early on July, 21, 1861, the morning of the First Battle of Manassas (First Bull Run in the North), and Confederate Colonel Nathan G. Evans was already in a tough spot. In command of a small 1,100-man brigade, Evans was posted behind the Stone Bridge crossing of Bull Run, the extreme left of Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard’s 8-mile-long defensive line. And the Federal build-up in his front had begun early. It started with picket firing. Then, at first light, the enemy deployed 6,000 men opposite his position. At 5:15 a.m., a large Federal 30-pounder Parrott rifle and other rifled cannon opened up on his concealed forces. Overmatched, Evans’ two 6-pounder smoothbores did not return the fire.

When enemy skirmishers advanced, Evans deployed three of his companies along Bull Run. Now shouts and rifle fire echoed throughout the river bottom. Strangely, this combat continued, without intensifying, until 8:30 a.m., when Evans received word from a signal officer that a large Union flanking column had been spotted approaching Sudley Ford, two miles to his left rear.

The time had come for a decision, perhaps the most crucial of Evans’ entire life. He was no doubt grateful that his Prussian orderly was standing by with the one-gallon wooden whiskey jug he called his “barrelito.”

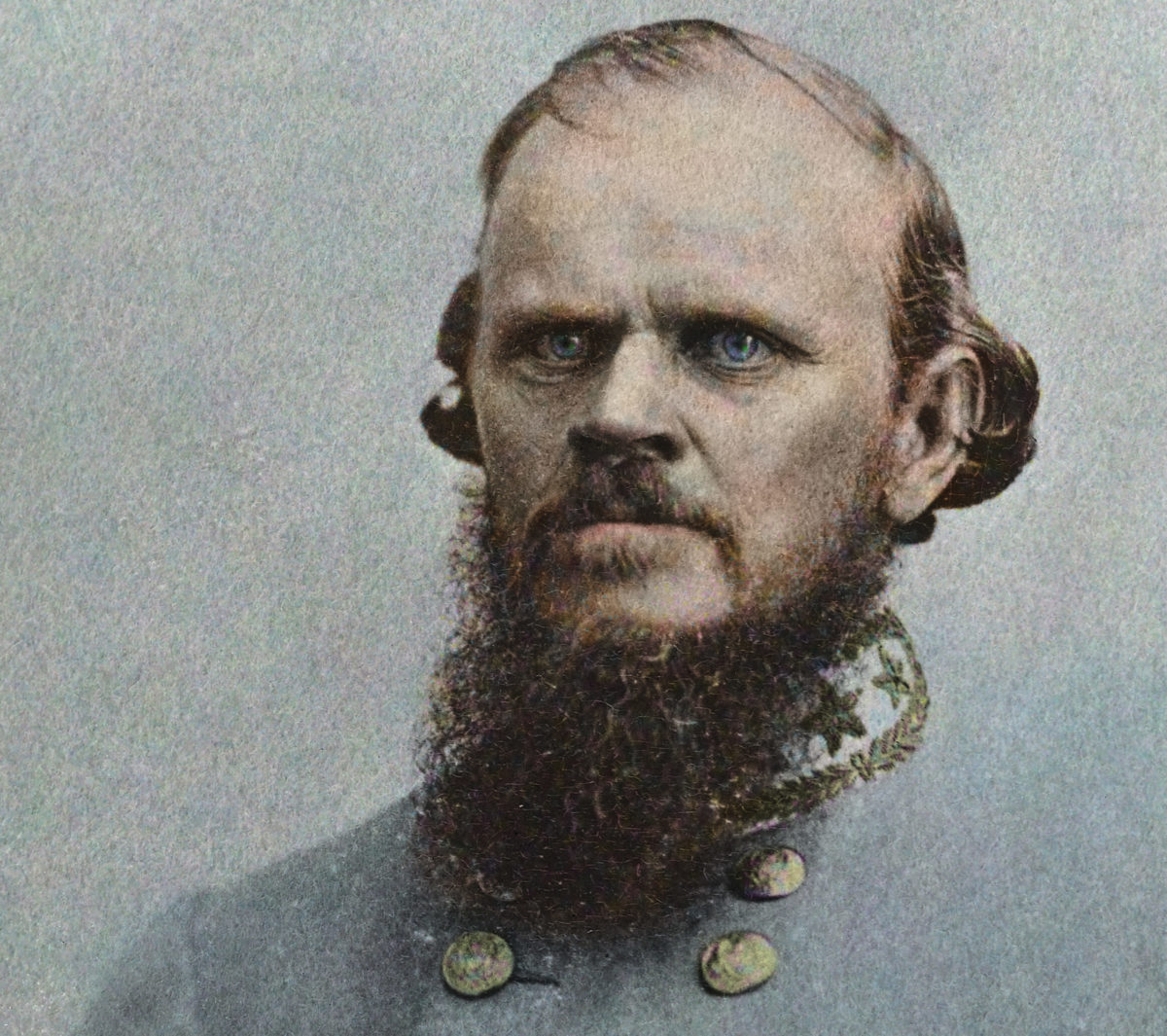

Colonel Nathan Evans was a thoroughly unique Confederate officer. Stern-faced, with a full beard, high forehead, and piercing eyes that made him look like a church elder, he was—to the contrary—roughhewn, arrogant, ill-mannered, and highly disrespectful of orders and authority. His fondness for alcohol was legendary. But Evans was also absolutely fearless, and in the Civil War’s early days he racked up quite an impressive record. By mid-war, however, his star quickly began to fade.

Early Success

Nathan George Evans was born in Marion, South Carolina, on February 3, 1824. In 1848 he graduated from West Point—a lowly thirty-sixth out of thirty-eight cadets (although 40 other classmates resigned or were dismissed before graduation)—where his classmates included future Union generals John Buford and John C. Tidball, and where Evans acquired his enduring nickname. A fellow graduate remembered Evans as “a wimble-jointed youth… who from his knock-kneedness was dubbed ‘Shanks.’”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Brevetted 2nd lieutenant, Shanks served out west with the 1st and 2nd U.S. Dragoons, attaining the rank of captain while gaining a reputation as an Indian fighter. When South Carolina seceded, he resigned his U.S. Army commission, offered his services to his home state, and on February 27, 1861, was made adjutant general of South Carolina forces with the rank of major.

Present at the April 12-13 bombardment of Fort Sumter, the following month Evans reported to Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction, Virginia. Beauregard—after making Shanks a temporary colonel—stationed him on his Bull Run line in command of the 4th South Carolina; the 1st Louisiana Special Battalion, “Wheat’s Tigers”; two companies of Virginia cavalry; and two 6-pounder smoothbore cannon. These forces comprised Evans’ demi-brigade two months later on the morning of July 21 when, while facing a division-size force, he learned that an enemy turning column of unknown strength was on his flank and approaching fast.

Shanks made his crucial decision quickly. Sensing that the force in his front was merely a diversion, he “at once decided to quit [his] position” and meet the enemy moving against his left. Leaving four companies at the Stone Bridge, Shanks double-quicked the balance to the southern slopes of Matthews Hill. There he deployed his infantry to the right of the main road from Sudley Ford. Cavalry and artillery bolstered both flanks. Well-positioned, and well-covered by the reverse slope, Evans’ men were ordered to open fire “as soon as the enemy approached within range of [their] muskets.”

They didn’t have long to wait. At 9:15 a.m., the head of the Federal column—skirmishers from the 2nd Rhode Island, of Colonel Ambrose E. Burnside’s brigade—burst out of the woods and onto Matthews Hill, triggering a vigorous Southern volley. It was unexpected, but Burnside now threw forward the balance of the 2nd Rhode Island, as well as its attached 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, which unlimbered its rifled guns but 200 yards from Evans’ line—point-blank range. Fortunately for Shanks, the gunpowder smoke that now shrouded Matthews Hill hid his small numbers.

Soon, Burnside brought the rest of his brigade into line—three more regiments and two more pieces of artillery—and another Union brigade jogged up the road and deployed against Evans’ left. Simultaneously, more Federal artillery unlimbered facing his left. Shanks’s 900 men were now facing about 4,500 of the enemy. And another 9,000 were strung out along the road, heading his way. He was still determined, nonetheless, to hold on as long as possible.

Bowie Knives And Musket Fire

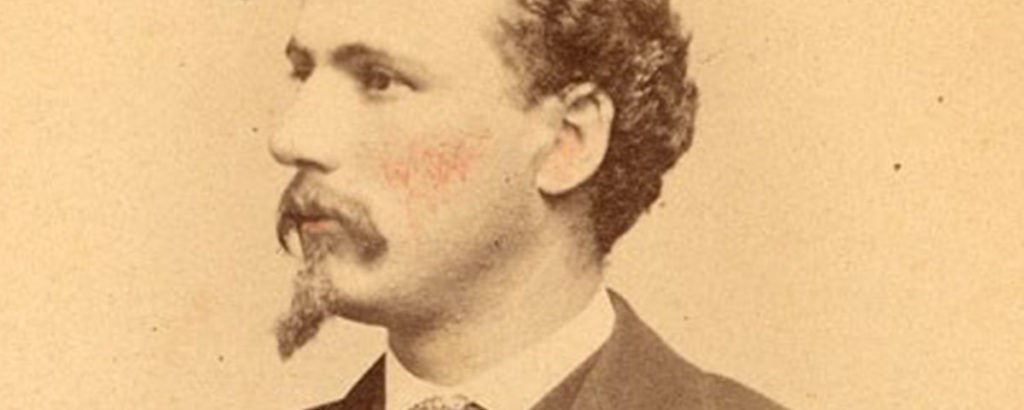

At approximately 10:45 a.m., thinking that he saw a weakness in the enemy center, Evans ordered Wheat’s Tigers to charge. Recruited from street toughs, former convicts, and Irish dockworkers from the port of New Orleans and dressed mostly as zouaves, these ruffians were commanded by the only man who could handle them: Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, a six-foot-four, 240-pound lawyer who’d fought in Mexico, South America, and Italy.

With the massive Wheat out front, saber waving overhead, the battalion surged forward, heading directly toward the Rhode Island guns. As the unit closed within 20 yards, many of the Louisiana rowdies tossed aside their rifles and drew their bowie knives. Others fired, taking down both artillerymen and horses. One Rhode Islander remembered this as “the most terrible moment of this terrific contest.”

The attack startled the enemy, but it was ill-timed. Receiving a close-range volley, Wheat’s Tigers staggered, and then tumbled backward. Its losses were heavy, and included Wheat himself, who took a bullet through both lungs.

At first, Wheat’s failed attack seemed to be Evans’ last hurrah.

But reinforcements soon arrived, 2,800 men under Brigadier General Bernard Bee, and Colonel Francis S. Bartow, and formed on Shanks’s immediate right. The enemy infantry was nearby, within a few hundred yards. And the Federal artillery was firing furiously. “I felt that I was in the presence of death,” wrote one of Bartow’s men. “This is unfair; somebody is to blame for getting us all killed.”

Federal reinforcements continued to arrive, and yet the Confederates launched another attack. Lurching forward, the Southerners faced a whirlwind of canister and musket fire. It was too much. “[T]he enemy by this time were in such large force that our position was no longer tenable,” wrote Evans, “and I ordered my command, now greatly scattered, to fall back.” The jumbled mob that was Evans, Bee, and Bartow’s commands streamed toward the rear. A few of Shanks’s men later resumed the fight with other units, but Evans’ demi-brigade no longer existed. He had sacrificed his little force but he’d bought precious time for Confederate forces.

Around noon, a new Confederate battleline congealed on Henry Hill, centered around a Virginia brigade commanded by Brigadier General Thomas J. Jackson (soon to be nicknamed “Stonewall” by General Bee). Southern reinforcements extended Jackson’s flanks, and for that afternoon vicious, close-range fighting raged back and forth across the Henry Hill plateau. Further Confederate reinforcements sealed the deal, however, and by 5:00 p.m. the Union army had disintegrated, the disorganized remains routing in retreat.

The Confederate victory at First Bull Run (First Manassas to the South) was exhilarating, but the losses were sobering. Confederate casualties totaled 1,982 men killed, wounded, or missing. Of the Southerners who’d stalled the enemy on Matthews Hill, Evans’ demi-brigade lost 144 men killed, wounded, or captured, while Bee and Bartow’s losses numbered 686, a brutally high butcher’s bill. Additionally, Wheat was out of action, and General Bee was killed on Henry Hill, as was Colonel Bartow.

“It is fit,” Beauregard (promoted to full general on July 21) noted in his after-action report, “that I should… commend to notice the dauntless conduct and imperturbable coolness of Colonel Evans.” Modern-day writers frequently cite Evans’ Matthews Hill stand as one of the main reasons Southern arms prevailed. “Indeed, Evans was virtually alone in the first crucial hours,” wrote historian William C. Davis, “when [the Federal] flanking column had to be stopped.”

“An Awful Spectacle”

In the July 25 reorganization of General Beauregard’s forces, Evans was given a brigade comprising the 13th, 17th, and 18th Mississippi Regiments. Soon thereafter, when he was officially promoted to colonel—not brigadier general, the rank he thought he deserved—Shanks complained directly to General Robert E. Lee (then Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s military adviser). The disappointing reply read that Lee “could not make the arrangements.”

On August 11, 1861, Colonel Evans’ brigade was ordered to Leesburg, Virginia, a town just off the Potomac River 20 miles upstream from Washington, D.C. There, Shanks also took command of a battery of artillery—of the Richmond Howitzers—the 8th Virginia Infantry Regiment under Colonel Eppa Hunton, and 300 Virginia cavalrymen under Lieutenant Colonel Walter H. Jenifer. Altogether, his forces numbered about 1,800 officers and men.

Meanwhile, in the smoky camps outside Washington, Union Major General George B. McClellan was organizing what became his massive Army of the Potomac. He soon took an interest in maneuvering Evans out of Leesburg. When “Little Mac” advanced a 12,000-man division that threatened Evans from the southeast, Union Brigadier General Charles P. Stone ordered a 2,000-man brigade to feint an attack across Edward’s Ferry (thus also menacing Evans from the east).

Simultaneously, Stone sent a scouting party across the Potomac via Harrison’s Island and Ball’s Bluff (a precipitous 70-foot-high ridgeline fronting the river northeast of Leesburg). When it reported back that this northern route to Leesburg was lightly defended, Stone, the next morning, ordered 400 Massachusetts infantrymen across the Potomac. They quickly encountered Confederate pickets and a brisk skirmish commenced.

It was now October 21st, three months to the day since First Manassas, and once again Shanks was facing overwhelming odds and a flanking force. Once again, he decided to fight. He blocked the enemy’s division with the 8th Virginia, while he remained on the main road from Edward’s Ferry to Leesburg with three Mississippi infantry regiments. To contain the Ball’s Bluff incursion, Shanks sent 200 Mississippi infantrymen and 70 Virginia cavalrymen under the overall command of Lieutenant Colonel Jenifer. As the fighting intensified, Evans rushed the 8th Virginia to Jenifer’s support.

In the late morning, Union Colonel Edward D. Baker, a U.S. Senator from Oregon and personal friend of Abraham Lincoln’s, arrived at Harrison’s Island, took command, and made the disastrous decision to ferry more troops into Virginia. This was slow-going because of the paucity of boats. Gunfire suddenly ran up and down the lines. Colonel Hunton, now in command on the field, launched an attack that drove the Federals back. Running low on ammunition, he sent a message to Evans pleading for reinforcements.

“Tell Hunton to hold the ground,” replied Shanks, “until every damn man falls.”

Then Evans dispatched the 18th and 17th Mississippi Infantry Regiments to Hunton’s aid.

Mid-afternoon, when the battle reached its crescendo, Colonel Baker had his 2,000 troops mostly arrayed across the top of the bluff facing a 10-acre open field. Unfortunately, the Confederates had him encircled. At 4:30 p.m., Baker was hit by four bullets and immediately killed. In the confusion that followed, a disastrous Union breakout attempt triggered a disorganized retreat. Another Confederate attack created a panic.

“Then ensued an awful spectacle,” penned a Virginian. “A kind of shiver ran through the huddled mass upon the brow of the cliff… then, in one wild, panic-stricken herd, [it] rolled, leaped, [and] tumbled over the precipice!” In the crazy rush down Ball’s Bluff—further impelled by Southerners firing from above—Union soldiers were impaled on the bayonets of those below. Boats along the river were quickly overcrowded and sank. Northerners drowned attempting to swim back to Harrison’s Island. Over the next several days, blackened, bloated, Union bodies floated downstream past Washington City.

Recommended for you

Another battle, another well-fought victory for Shanks Evans. Though not physically present on the battlefield, he’d handled his outnumbered forces admirably, identifying the feints and rushing reinforcements to the actual threat. At Ball’s Bluff, Union losses totaled 1002: 223 killed; 226 wounded; and 553 captured. In contrast, Shanks reported losing 153 killed and wounded, and two taken prisoner.

Pride Before A Fall

The praise was immediate. “The General congratulates you heartily for your brilliant success of yesterday,” read the message from Beauregard. “Sound the bugles, roll the drums, wave the banners, shout out the loudest huzzas, for the gallant Evans and his Spartan band at Leesburg,” added the Charleston Mercury. From the Confederate Congress and the Mississippi Legislature came official thanks: His native state voted him a medal. Evans’ coveted promotion to brigadier general followed quickly, dating from October 21, 1861.

Ordered to South Carolina on the request of the governor, Evans arrived in mid-December. On June 15, 1862, Shanks was put in charge of South Carolina’s First Military District. In mid-July, in response to Richmond’s call for more troops, Evans was dispatched to Virginia in command of the 17th, 18th, 22nd, and 23rd South Carolina Volunteers, the Holcombe South Carolina Legion, and attached artillery. Over the next year, this force traveled so many miles that it became known as the “Tramp Brigade.”

Six weeks later, at Second Manassas (Second Bull Run in the North), on August 30, Evans—commanding his own brigade and another under Hunton—participated in the wildly successful Southern attack that crushed the Union left. His South Carolinians suffered 734 casualties in this Confederate victory. “I was under fire the whole time,” he wrote his wife. “The woods in our rear are strewn with the dead Yankees. The stench is awful.”

On the march to Maryland, Lee’s first invasion of the North and capitalizing on his Second Manassas victory, Evans argued with Brigadier General John B. Hood over the ownership of Federal ambulances captured by Hood’s men. Evans ordered Hood to turn them over to his South Carolinians.

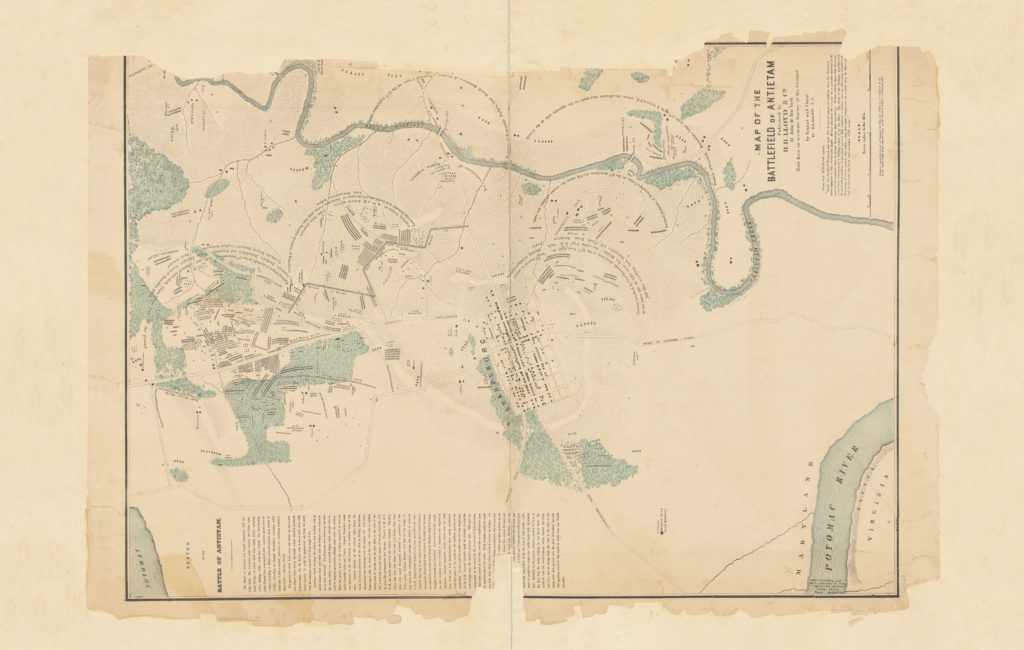

When Hood refused—“I did not consider it just,” he later wrote—Evans placed him under arrest. Army commander Lee interceded, however, ordering Hood to remain with his troops. The next month, Shanks’s brigade fought at both South Mountain on September 14, and Sharpsburg (Battle of Antietam) three days later, losing a total of 290 officers and men. “This battle was the greatest I have been in,” he penned his wife after Sharpsburg.

Ordered to North Carolina in November, Evans, with his headquarters at Kinston, took command of the Confederate troops between the Neuse and Roanoke Rivers. When a 10,000-man Federal force advanced against him on December 14, Shanks retired behind the Neuse and ordered a bridge burned. Unfortunately, not all of his men had crossed and 400 were forced to surrender. Kinston was subsequently looted by the enemy.

Afterwards, stories circulated that Shanks had been intoxicated at Kinston (as well as earlier during the fighting at South Mountain). Though fully acquitted in February 1863 by a court of inquiry, Evans felt that the negative publicity helped rob him of his much-deserved promotion to major general.

From Kinston Evans’ brigade was ordered to Cape Fear, and from there to Charleston in mid-April. Dispatched in May to Mississippi to General Joseph E. Johnston’s army in its ultimately unsuccessful efforts to help relieve Confederate forces which soon thereafter were besieged in Vicksburg. Evans and his South Carolinians saw no action as Johnston dallied, Vicksburg fell on July 4th, and Evans’ command was back in Charleston by late August.

The Unraveling

Now Evans’ military career really began to unravel. When he assumed command of the 2nd Sub-Division of South Carolina’s First Military District, he immediately started quarreling with his superior, Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley (a man whose fractious disposition equaled Evans’ own). Ripley issued orders that Shanks evidently resented.

Then, following a tempestuous face-to-face, Ripley wrote Evans that “[N]o departure or delay in executing orders in any way [will] be countenanced.” Feeling he’d been reprimanded, Evans wrote back relating his surprise “at the tenor” of his commander’s letter.

An even bigger surprise arrived on September 20 when Shanks was relieved of command and placed under arrest. Evans appealed directly to Beauregard, then in charge of the defense of the southeast Confederate coast, but this letter produced only a disappointing response.

Evans’ court martial for disobedience of orders convened in Charleston on October 2, 1863. Ripley charged Evans with three counts of disobedience: he’d failed to clear the timber fronting his lines; he’d failed to relocate his headquarters, as ordered; and he’d failed to assist a colonel who was on special duty “collecting boats and water transportation.”

Later that month Evans learned that he’d been cleared of all charges, but because Beauregard declined to publish the court’s findings, he was now officially in a state of military limbo. Pressed about the matter, Beauregard replied that Evans’ units, according to reports, suffered from low morale and poor discipline. Returning Evans to his brigade, stated Beauregard, would further reduce its effectiveness.

In January 1864, Beauregard, under orders from the Richmond War Department, finally released Shanks from arrest, but he did not return him to command. Almost certainly, this was the consequence of Evans’ well-known alcoholism exacerbated by his general cantankerousness. “Evans was difficult to manage and we found him so,” wrote Confederate staff officer (and later Brigadier General) Moxley Sorrel, notably Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s adjutant-general.

Evans was much too fond of whiskey, “and there was the trouble.”

Ordered, in March 1864, to take command of his brigade and report, unfortunately, to General Ripley’s First Military District, Shanks Evans complained, asking to be assigned elsewhere. That opportunity presented itself on April 14 when he was instructed to proceed immediately to Wilmington, North Carolina. He never made it.

On April 16, while he was driving a two-horse buggy through downtown Charleston, a snapped trace caused the equines to rapidly pick up speed. This jolt broke the shaft, and Evans was violently yanked forward, headfirst, onto the unforgiving cobblestones. Onlookers who rushed to his side found him unconscious. He was bleeding from several head wounds, the skin from his high forehead completely scraped away. Evans was slow to recuperate. During this period, a rancorous dispute with one of his brigade’s colonels, which unfortunately played out in the newspapers, further stained Evans’ already tarnished reputation.

General Evans traveled to Richmond in the fall, hoping to receive an assignment that did not arrive until March 17, 1865, when the Confederacy was in its death throes. After President Davis and his cabinet fled Richmond on April 2 as Petersburg fell, Evans briefly joined the fleeing entourage, helping to escort it to Cokesbury, South Carolina.

After the war, Shanks failed at selling cotton, founded a school in Cokesbury, and eventually became principal of another school in Midway, Alabama. Shanks Evans—the hero of First Manassas and Ball’s Bluff—passed away on November 28, 1868, likely succumbing to the lingering effects of his buggy accident. He was just forty-four years old.