The city of Manassas, Va., however, is almost wholly a post-Civil War phenomenon. Where the name “Manassas” originated is uncertain. Some say it derived from the name of a Jewish peddler, Manasseh, whose territory encompassed some of Northern Virginia. It was sufficiently popular in March 1850 that the Virginia legislature gave it to a branch railroad that would connect the Orange & Alexandria

Railroad with the Shenandoah Valley. When the Manassas Gap Railroad was completed, in 1853, the point near the Tudor Hall farm, where the line diverged from the O&A, was named Manassas Junction.

Prince William County, where Manassas Junction was established, depended on agriculture but wasn’t suitable for tobacco production and never grew as wealthy as the Tidewater. Farms in the area included Liberia, a two-story Federalist style brick house constructed in 1825, home for William J. Weir and family, descendants of Robert “King” Carter, the original land patent holder for Northern Virginia.

Liberia was roughly a mile and a half north of the train depot, on high ground a short distance west of the Centreville Road (today’s Route 28).

The railroad junction supported a few homes and businesses, including Belcher’s Hotel, which like many railroad hotels of the time offered only primitive accommodations. “The walls were rushed up very much like a barn or stable, where the wind on cold nights would whistle through the…intervals of the planks, which were at least a half inch apart,” one disgruntled guest recalled. “The building was…heated…by an immense stove whose smoke all settled inside.”

Despite its isolation, the fact that the railroads crossed at Manassas made it a critical strategic point for both armies in the first years of the Civil War. In the spring of 1861, Union commander Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell reasoned that occupying the junction and cutting off the Manassas Gap and O&A lines from the Virginia Central Railroad offered control of the only continuous railroad connection from Alexandria, Va., across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., to Richmond. Troops and supplies could move from the Union depot at Alexandria to the front lines as McDowell’s army marched closer to the Confederate capital.

The Confederate commander, Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, recognized the importance of Manassas Junction, including the need to connect Richmond with the rich Shenandoah Valley, and in June 1861, encamped roughly 22,000 troops in a defensive alignment along Bull Run Creek, five miles northeast of Manassas Junction. The Rebel troops dug fortifications and cannon emplacements and waited for their foe.

On July 16, 1861, McDowell’s 35,000 green troops marched west from Alexandria. It took two days for the undisciplined soldiers to straggle their way to Centreville.

One of the few houses in the area to survive was Liberia. Confederate President Jefferson Davis visited just after First Manassas to confer with Beauregard and Johnston. In June 1862, President Abraham Lincoln called on McDowell there after the general’s horse had fallen on him.

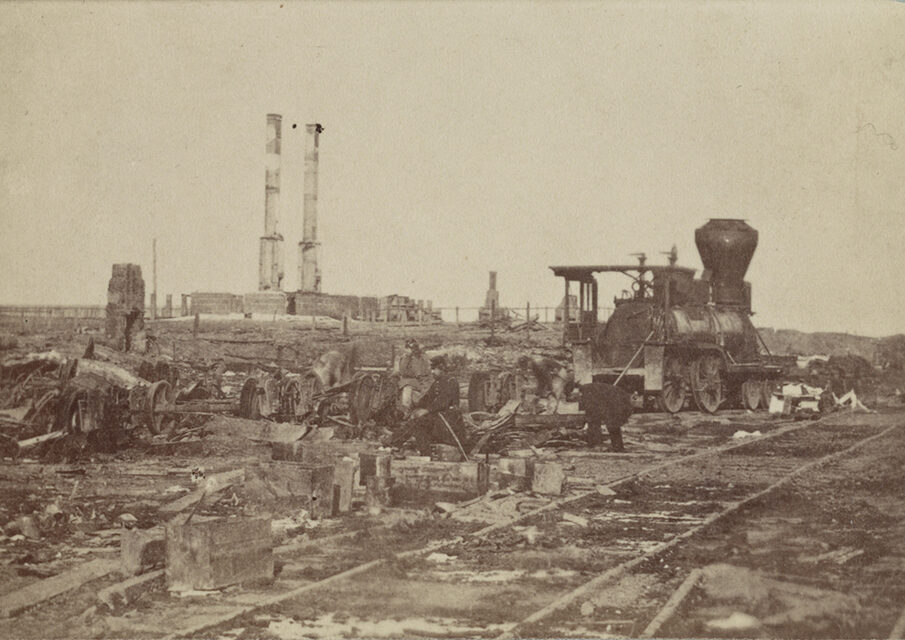

Union troops arriving to occupy the devastated depot immediately began rebuilding the railroads and buildings. The installation became a target for the Army of Northern Virginia in August 1862 after the failed Peninsula campaign. President Lincoln ordered the formation of a new primary fighting force to be called the Army of Virginia and put it under the command of brash Maj. Gen. John Pope. Pope’s objective was to break the Orange and Alexandria Railroad’s connection with the Virginia Central Railroad at Gordonsville, 50 miles southwest of Manassas. McClellan was to return with the Army of the Potomac to join forces with Pope.

Gen. Robert E. Lee, determined to strike before the Union armies established a numerical advantage, on August 25 sent Stonewall Jackson and half the Army of Northern Virginia (23,500 men) on a sweeping march from the Rappahannock River through Thoroughfare Gap around Pope’s right flank. In two days, Jackson’s men marched 56 miles and raided the Manassas Junction depot before establishing defensive positions near the Manassas battlefield. Pope, determined to act aggressively, marched north from the Rappahannock and attempted to locate and bring his force to bear against Jackson. Pope appealed to McClellan to move quickly to join their forces, but McClellan resisted, arguing his army was needed to defend Washington. On August 29, determining not to wait for McClellan, Pope attacked Jackson along the Manassas-Sudley Road, near the abandoned Manassas Gap Railroad cut. However, the Confederates withstood the assault, with the opposing armies each suffering heavy casualties. That day was marked by indecision by top commanders on both sides, with Union Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter defying Pope’s order to attack the Confederate right, where Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s entire corps was forming up, and Longstreet himself pressing Lee to remain on the defensive in the absence of strong intelligence about the size of the Union force he faced. That night, Pope mistook Confederate maneuvering for the start of a retreat and ordered Brig. Gen. John Hatch to attack Jackson on the morning of August 30. Longstreet counterattacked on the Union left and forced the Federals back. That night, Pope ordered a retreat across Bull Run, leaving the Confederates in control of the battlefield. The victory led Lee to invade Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam on September 17.

Most civilians left Manassas Junction and didn’t return until after the war when destruction of properties, the elimination of slavery, and the worthlessness of Confederate currency made land cheap. Desperately in need of cash, Virginia planters sold land at fire-sale prices to Northerners, many Pennsylvanians, and either sold land or gave it to their former slaves. By purchasing land, former slaves were often able to reunite their families.

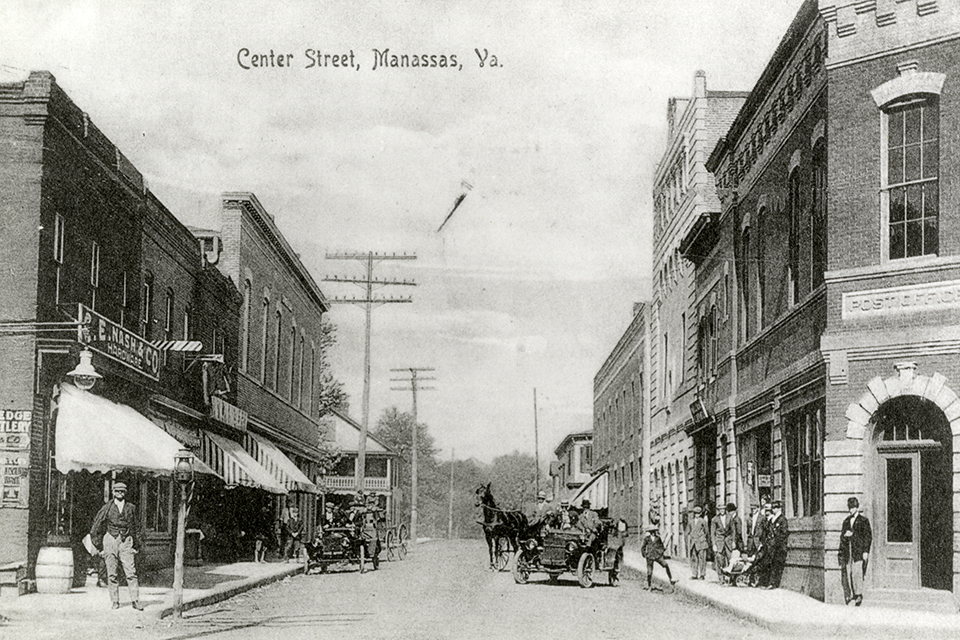

It may be fairly stated that the town of Manassas began on September 11, 1865, when New Yorker Sumner Fitts bought part of Block No. 1 “of a town lately laid out” by William S. Fewell. Fewell had inherited the land which now comprises Old Town Manassas in 1858. At war’s end he became the local railroad agent, recognizing the area’s growth potential. Presciently, he began to divide his land into blocks and lots, which he labeled the “town of Manassas,” in the Prince William county deed book. Fewell sold two lots in 1865, six entire blocks in 1866, and by May 1867, thirteen entire blocks had been sold, some running parallel on both sides of the railroad tracks. Wartime destruction had depressed land prices, and town lots were selling at $2–$8 an acre ($34 to $136 in 2018 dollars) Nevertheless, by spring 1869, encouraged by the railroad, a hotel and various stores and shops had appeared, and names had been given to five streets.

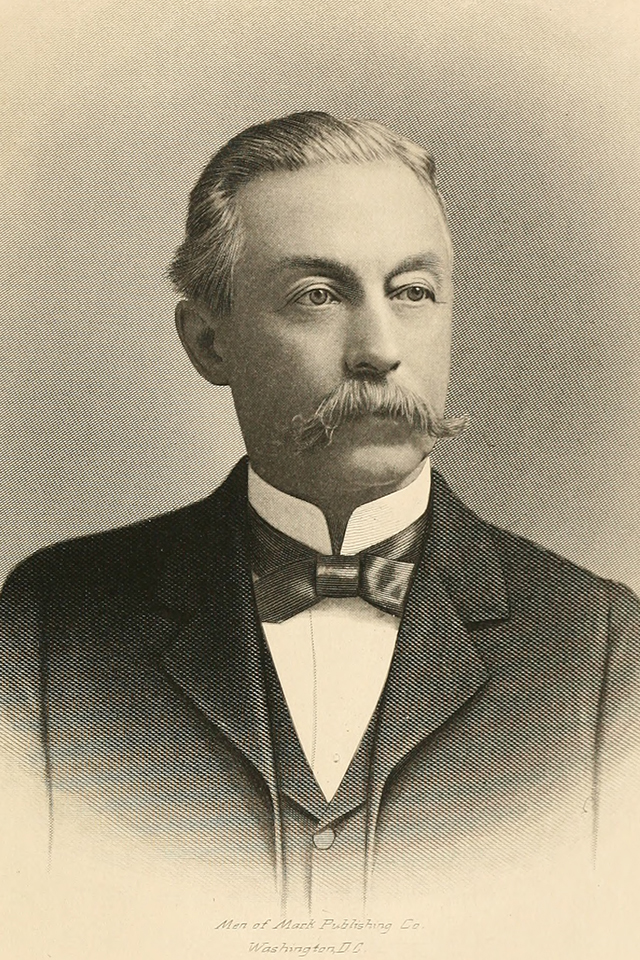

As Manassas expanded, it soon became known among the wealthy as a vacation/retirement destination, and attracted one of Virginia’s most successful businessmen, beer magnate Robert Portner. Portner came to the United States at age 16, in 1853, from Prussia. Migrating to Washington, D.C., in September 1861, he established a successful grocery store and brewery in nearby Alexandria. His business largely consisted of selling beer and groceries to Union troops. Portner earned respect when he successfully defied an order from the despotic military governor of Alexandria, Brig. Gen. John P. Slough, not to sell alcoholic beverages to the soldiers.

Portner’s connection with Manassas began early in 1869, when Christian Mathis, a Swiss immigrant and New Jersey saloon owner/hotel operator, called on him. Mathis was in poor health, looking to retire, and had recently purchased 25 acres of the Liberia farm from Robert Carter Weir for $800. Portner met his wife, Anna, at a dinner party hosted by Mathis at his Manassas home. Mathis’ health declined further, and he died on his farm in October 1875.

Portner purchased the 191-acre Mathis farm, for $6,000, renaming it Annaburg to honor a military academy he had attended as a youth. However, he soon realized that the farm’s ten-room home was insufficient for his large family. He purchased several other parcels of land, but in 1892, began construction of another mansion to replace the former Mathis home. The new Annaburg estate at the intersection of Portner Avenue and Main Street included a Colonial Revival style mansion, with neoclassical elements, containing 35 rooms on three floors and a basement. It featured three rarities: electric lights, indoor plumbing, and air conditioning based on the cooling system used in Portner’s brewery. The outer walls were sandstone, quarried locally, and brick. The 2,000-acre estate also contained a deer park, a lake, and a hunting lodge. Shortly after its 1894 completion, Annaburg was lauded as “one of the finest estates in Virginia,” and made a fine showpiece for the growing town of Manassas. Portner also purchased Liberia and established a large dairy there. The town gradually became the business center of Prince William County, and with railroad help, became the county seat in 1892.

It would take more than cheap land, business expansion, and showpiece estates to ensure steady future growth in Manassas.

War’s end saw the South totally prostrate—its railroads, bridges, and public works completely ruined; private property largely destroyed, its political and labor systems broken, with little demand for its cotton, and widespread unemployment and hunger. Making matters worse, defeat and Reconstruction’s harsh rules resulted in inept Federal administration, exploitation by those looking for quick profit, and fostered a contemptuous and defiant attitude toward Northerners, which a few Southerners have even today. President Lincoln strongly supported reconciliation, but in much of the South, cooperation was lacking. Suspicion towards the South remained strong among Northerners, especially after Lincoln’s assassination, which many in the North thought was a Confederate plot.

Into this difficult atmosphere, in 1868, stepped a former Union army lieutenant, George Carr Round, when on his way to Raleigh, N.C., he got off the train and first saw the tiny crossroads called Manassas. Sensing the potential of the nascent town, he realized that Manassas was where he might make his mark. A native of Easton, Pa., Round had grown up in Middletown, Connecticut. Enlisting in the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, Company G, in May 1861, while still in college, he was soon promoted to corporal. In March 1863, Round was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Signal Corps. Company G saw action at the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Va., July 30, 1864. The unit also served on the “Petersburg Express,” a railroad platform car on which was mounted a 13-inch seacoast mortar, which effectively checked enfilading enemy fire. Round’s company also saw action at the siege of Fort Fisher, N.C., in mid-January 1865. War’s end found Round in Raleigh, N.C., under the command of Maj. Gen. John Schofield. Ordered to establish a signal station on the state capitol dome, Round searched in vain for a way to the top. Mistaking the dome top, in the dark, for a solid surface, he attempted to jump onto it, but instead crashed through the glass skylight. A wire netting saved him from falling 100 feet to his death. Some days later, after hearing of the war’s end, using signal rockets, Round wrote the cipher-coded message, “Peace on earth, good will to men,” in the sky. Graduating from Columbia Law School after the war, Round headed south to visit his uncle’s family in Raleigh but went no farther than Manassas.

By January 1, 1869, Round had opened a law practice, based on assisting loyal landowners to make claims against the Federal government for reimbursement on property stolen or destroyed by the Union Army. He also sold real estate, but education was where Round made his mark. In 1869, he was named district superintendent of schools for Prince William County. The trustees of the county school board, including Round, soon opened the Manassas Village School, for the town’s white children, in the Asbury Methodist church. Private funds were used, as no public funds had yet been collected. The Peabody Fund, based in Baltimore, contributed $300 in 1869, and $300 in 1870. The remaining $694.24 required was given by donors north of the Mason-Dixon Line. For its first two years, the Village School met in Manassas’ Asbury Methodist Church. Sufficient funds were raised by spring 1872, to begin building a new school, designed by Round, who also supervised its construction. Completion was in July 1872, and the school was named Ruffner School No. 1, for Virginia’s first school superintendent, William Ruffner. The school was enlarged in 1908 to accommodate Manassas High School but overcrowding forced its closure in 1926. Round’s tireless efforts also established an agricultural school, and he strongly supported the Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth. Round helped write the 1873 town incorporation charter, establishing a town council. He was the first town clerk and donated the land for the county courthouse. He planted dozens of shade trees throughout Manassas, and by his solicitation, he got millionaire philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to donate funds for city and school libraries in 1900.

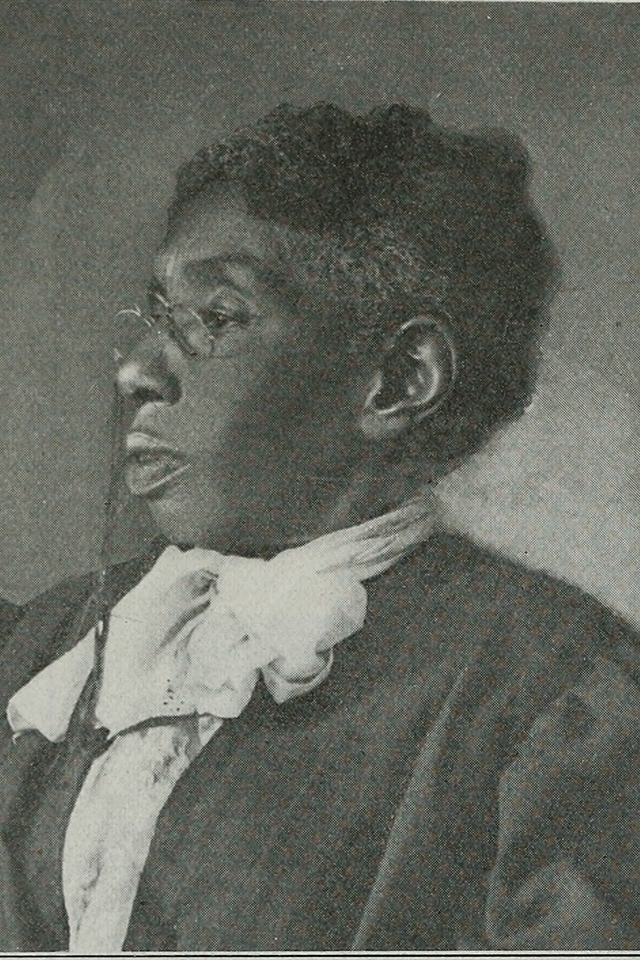

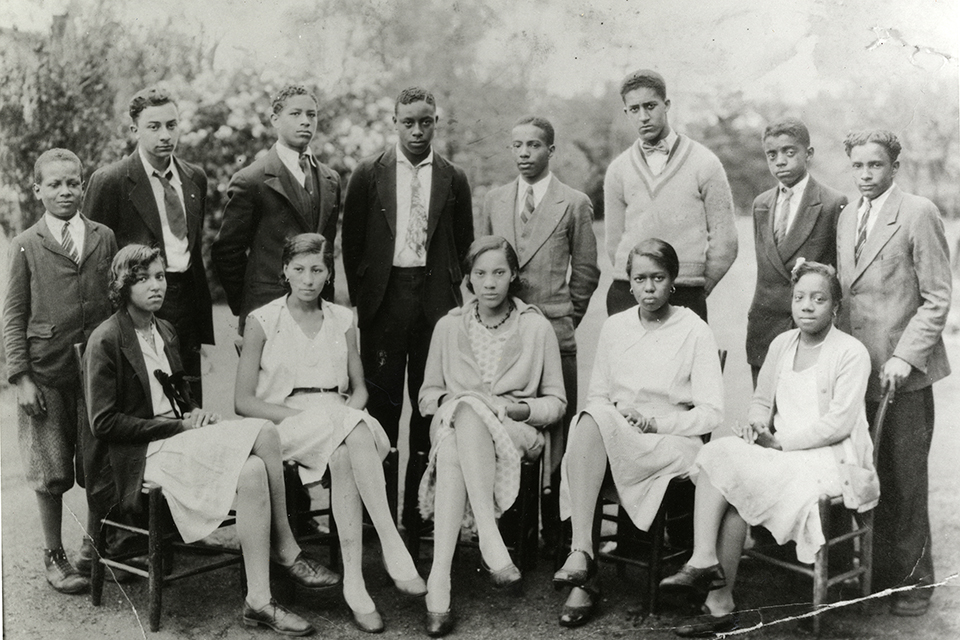

For a century after the Civil War, Manassas remained a segregated city. Schools, churches, clubs, and public accommodations were maintained separately for whites and blacks. Efforts to offer education to African Americans were led by Jane “Jennie” Serepta Dean, who went to work at age 14 as a domestic in Washington, D.C., to help her father, former slave Charles Dean, pay down his mortgage, and help her siblings pay for their education. After some years in Washington, Jennie Dean would return to Manassas to found a school, the Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth, where black teenagers were taught carpentry, sewing, shoemaking, and metal-working skills. The school opened in 1894, and even after the 1913 death of Jennie Dean, it continued to grow, offering an academic curriculum along with trades and attracting male and female students from other communities to live in dormitories on its campus. After the 1938 closure of the Industrial School, the facilities were bought and operated by Prince William, Fairfax, and Fauquier counties as a regional high school for black students. Segregation continued even after the 1954 Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision and Prince William County in 1959 built a new school for black students named Jennie Dean High and Elementary School. Prince William County integrated its public schools in 1966.

The separation of the races remained the status quo in Manassas long after a 1911 event cemented reconciliation between North and South. The Manassas National Jubilee of Peace was first suggested by a Confederate veteran in a letter to the editor published in The Washington Post, in January 1911. Reading the letter, Round liked the idea, and by July, President William Howard Taft, Virginia Governor William Hodges Mann, numerous senators and congressmen, 600 veterans from both sides, the 15th U.S. Cavalry and a band from Fort Myer, Va., had agreed to participate.

The festivities began on July 16. Flags and patriotic bunting engulfed the town, and a local newspaper declared, “It is the duty of every citizen to decorate.” The Southern Railway promoted the event for weeks, offering reduced round-trip fares. Veterans met on Henry Hill Friday, July 20. A double line of Confederate veterans, numbering 350, stood facing north, while 12 yards away a line of Union veterans, about 175, faced south. At a signal, both lines advanced, clasped hands, promised eternal friendship, and discussed events of “50 years ago.” On the last day, various dignitaries, including Mann, Grand Army of the Republic commander Gen. James E. Gilman, and United Confederate Veterans chief Brig. Gen. George W. Gordon gave battlefield speeches.

Taft was due in Manassas at 4 p.m., but as the first president with an automobile, he decided to drive from Washington, following the route politicians and picnickers had taken to First Manassas in 1861. The four-car presidential caravan left the White House a little after noon on July 21. They were plagued by choking dust, a rainstorm, and flooded streams. Scrupulously observing Virginia law, Taft stopped to calm horses frightened at the convoy’s approach, and also stopped to dine at Falls Church and Fairfax. Three cars were left behind, when they encountered high water, while attempting to cross Rocky Run and Bull Run, and Taft’s car barely made it across. Arriving at 5:30 p.m., Taft’s party was greeted by a crowd of about 600, at Main and Church streets, and escorted to the enclosure at the nearby courthouse, where the Jubilee Committee, led by Round, greeted them. A crowd estimated at 10,000 was inside. Behind Taft on the reviewing stand were 48 young women, Peace Maidens, representing the states and mainland territories of the Union, who sang the Jubilee Anthem, “United.” Round’s daughter Ruth represented Rhode Island.

The Jubilee was a great success, and Taft’s remarks left few dry eyes in the crowd. Referring to the Civil War’s great loss of life and suffering, Taft declared that he deplored war and wished it could be abolished. “Those who had experienced war,” he stated, “know what it is and want no more of it.” Telling the veterans that he looked to them “to aid in the movement for peace,” Taft announced that both England and France had agreed to enter into an arbitration treaty with the United States. This agreement provided for international arbitration, “for every issue which cannot be solved by negotiation,” and was signed in August, shortly after the Jubilee. However, it was never ratified, and soon forgotten, in the cataclysm of World War I. The Jubilee’s success was further reflected in the fact that Round had received “over a thousand letters and postals in response to the call for a Jubilee,” and with one exception on each side, “all are in perfect accord with the spirit of the Jubilee.”

That spirit was tested soon afterwards, when the Washington Post, on July 23rd, published two “specials,” denouncing the Jubilee. A Union veteran attendee, James E. Maddox, presumably from Erie, Pa., charged that the women of Manassas, in disrespectful tones, had refused water to the 15th U.S. Cavalry, Troops C and D, “because they wore the uniform of the United States army.” He also charged that thievery ran rampant at the Jubilee. Round and other Jubilee officials vigorously denied the charges. In a Manassas Democrat column, Round denounced both specials, calling the one datelined Manassas “fabricated and false,” sent by a reporter “whose intention was to scorch the people of Manassas and the Jubilee.” He further stated, “The statement that Southern women denied water to Union veterans has no foundation in fact. The water at Henry Hill gave out at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and all alike were so informed. The best women of Prince William County, including the Daughters of the Confederacy…personally served a free luncheon to all present, and more than twelve baskets were left,” and “The officers and men of the Fifteenth United States cavalry emphatically and indignantly deny that they have any cause for complaint of treatment by anyone.” The thievery charge was likewise shown to be false. In an open letter to The Washington Post, Round called on the newspaper to retract the specials and apologize. The Post never did either.

The Jubilee sparked widespread interest in Manassas, resulting in Manassas battlefield becoming a National Battlefield Park and landmark, in May 1940, after a long campaign. And the once sleepy crossroads grew from a town into a city, standing today as a testament to what determination born of devastation, opportunity, and good will can achieve.