The announcement of an upcoming “Woman’s Rights Convention” in the Seneca County Courier was small, but it attracted Charlotte Woodward’s attention. On the morning of July 19, 1848, the 19-year-old glove maker drove in a horse-drawn wagon to the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in the upstate New York town of Seneca Falls. To her surprise, Woodward found dozens of other women and a group of men waiting to enter the chapel, all of them as eager as she to learn what a discussion of “the social, civil, and religious rights of women” might produce.

The convention was the brainchild of 32-year-old Elizabeth Cady Stanton, daughter of Margaret and Judge Daniel Cady and wife of Henry Stanton, a noted abolitionist politician. Born in Johnstown, New York, Cady Stanton demonstrated both an intellectual bent and a rebellious spirit from an early age. Exposed to her father’s law books as well as his conservative views on women, she objected openly to the legal and educational disadvantages under which women of her day labored. In 1840 she provoked her father by marrying Stanton, a handsome, liberal reformer and further defied convention by deliberately omitting the word “obey” from her wedding vows.

Marriage to Henry Stanton brought Elizabeth Cady Stanton—she insisted on retaining her maiden name—into contact with other independent-minded women. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London where, much to their chagrin, women delegates were denied their seats and deprived of a voice in the proceedings. Banished to a curtained visitors’ gallery, the seven women listened in stunned silence as the London credentials committee charged that they were “constitutionally unfit for public and business meetings.” It was an insult Cady Stanton never forgot.

Recommended for you

Among the delegates was Lucretia Coffin Mott, a liberal Hicksite Quaker preacher and an accomplished public speaker in the American abolitionist movement, who was also disillusioned by the lack of rights granted women. A mother of six, Mott had grown up on Nantucket Island, “so thoroughly imbued with women’s rights,” she later admitted, “that it was the most important question of my life from a very early age.” In Mott, Cady Stanton found both an ally and a role model. “When I first heard from her lips that I had the same right to think for myself that Luther, Calvin and John Knox had,” she recalled, “and the same right to be guided by my own convictions . . . I felt a new born sense of dignity and freedom.” The two women became fast friends and talked about the need for a convention to discuss women’s emancipation. Eight years passed, however, before they fulfilled their mutual goal.

For the first years of her marriage, Cady Stanton settled happily into middle-class domestic life, first in Johnstown and subsequently in Boston, then the hub of reformist activity. She delighted in being part of her husband’s stimulating circle of reformers and intellectuals and gloried in motherhood; over a 17-year period she bore seven children. In 1847, however, the Stantons moved to Seneca Falls, a small, remote farming and manufacturing community in New York’s Finger Lakes district. After Boston, life in Seneca Falls with its routine household duties seemed dull to Cady Stanton, and she renewed her protest against the conditions that limited women’s lives. “My experience at the World Anti-provided the opportunity to take action.

On July 13 Cady Stanton received an invitation to a tea party at the home of Jane and Richard Hunt, wealthy Quakers living in Waterloo, New York, just three miles west of Seneca Falls. There she again met Mott, her younger sister, Martha Coffin Wright, and Mary Ann McClintock, wife of the Waterloo Hicksite Quaker minister. At tea, Cady Stanton poured out to the group “the torrent of my long-accumulating discontent.” Then and there, they decided to schedule a women’s “convention” for the following week. Hoping to attract a large audience, they placed an unsigned notice in the Courier, advertising Lucretia Mott as the featured speaker.

Near panic gripped the five feminists as they gathered around the McClintocks’ parlor table the following Sunday morning. They had only three days to set an agenda and prepare a document “for the inauguration of a rebellion.” Supervised by Cady Stanton, they drafted a “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions,” paraphrasing the Declaration of Independence. The document declared that, “all men and women are created equal” and “are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights…” These natural rights belong equally to women and men, but man “has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and to her God.” The result has been “the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.”

There followed a specific catalog of injustices. Women were denied access to higher education, the professions, and the pulpit, as well as equal pay for equal work. If married, they had no property rights; even the wages they earned legally belonged to their husbands. Women were subject to a different moral code, yet legally bound to tolerate moral delinquencies in their husbands. Wives could be punished, and in a case of divorce, a mother had no child custody rights. In every way, man “has endeavored to destroy [woman’s] confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-esteem, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.” Above all, every woman had been deprived of “her inalienable right to the elective franchise.”

Eleven resolutions demanding redress of these and other grievances accompanied the nearly 1,000 word Declaration. When Cady Stanton insisted upon including a resolution favoring voting rights for women, her otherwise supportive husband threatened to boycott the event. Even Lucretia Mott warned her, “Why Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous!” “Lizzie,” however, refused to yield.

Although the gathering was a convention for and of women, it was regarded as “unseemly” for a lady to conduct a public meeting, so Lucretia’s husband, James Mott, agreed to chair the two-day event. Mary Ann McClintock’s husband, Thomas, also participated. Henry Stanton left town.

When the organizers arrived at the Wesleyan Chapel on the morning of Wednesday, July 19th, they found the door locked. No one had a key, so Cady Stanton’s young nephew scrambled in through an open window and unbarred the front door. As the church filled with spectators, another dilemma presented itself. The first day’s sessions had been planned for women exclusively, but almost 40 men showed up. After a hasty council at the altar, the leadership decided to let the men stay, since they were already seated and seemed genuinely interested.

Tall and dignified in his Quaker garb, James Mott called the first session to order at 11:00 A.M., and appointed the McClintocks’ older daughter (also named Mary Ann) as secretary. Cady Stanton, in what was her first public speech, rose to state the purpose of the convention. “We have met here today to discuss our rights and wrongs, civil and political.” She then read the Declaration, paragraph by paragraph, and urged all present to participate freely in the discussions. The Declaration was re-read several times, amended, and adopted unanimously. Both Lucretia Mott and Cady Stanton addressed the afternoon session, as did the McClintocks’ younger daughter, Elizabeth. To lighten up the proceedings, Mott read a satirical article on “woman’s sphere” that her sister Martha had published in local newspapers. Later that evening, Mott spoke to a broader audience on “The Progress of Reforms.”

The second day’s sessions were given over to the 11 resolutions. As Mott feared, the most contentious proved to be the ninth–the suffrage resolution. The other 10 passed unanimously. According to Cady Stanton’s account, most who opposed this resolution did so because they believed it would compromise the others. She, however, remained adamant. “To have drunkards, idiots, horse racing rum-selling rowdies, ignorant foreigners, and silly boys fully recognized, while we ourselves are thrust out from all the rights that belong to citizens, is too grossly insulting to be longer quietly submitted to. The right is ours. We must have it.” Even Cady Stanton’s eloquence would not have carried the day but for the vocal support she received from Frederick Douglass, the ex-slave and abolitionist editor of the North Star. “Right is of no sex,” he argued; woman is “justly entitled to all we claim for man.” After much heated debate, the ninth resolution passed—barely.

Thomas McClintock presided over the final session on Thursday evening, during which he read extracts from Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England that described the status of women in English common law. Short speeches by young Mary Ann McClintock and Frederick Douglass followed the reading of a poem by Cady Stanton, which was in reply to a pastoral letter signed by the “Lords of Creation.” Lucretia Mott closed the meeting with an appeal to action and one additional resolution of her own: “The speedy success of our cause depends upon the zealous and untiring efforts of both men and women, for the overthrow of the monopoly of the pulpit, and for securing to women of equal participation with men in the various trades, professions, and commerce.” It, too, passed unanimously.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

In all, some 300 people attended the Seneca Falls Convention. The majority were ordinary folk like Charlotte Woodward. Most had sat through 18 hours of speeches, debates, and readings. One hundred of them—68 women (including Woodward) and 32 men—signed the final draft of the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions. Women’s rights as a separate reform movement had been born.

Press coverage was surprisingly broad and generally venomous, particularly on the subject of female suffrage. Philadelphia’s Public Ledger and Daily Transcript declared that no lady would want to vote. “A woman is nobody. A wife is everything. The ladies of Philadelphia, . . . are resolved to maintain their rights as Wives, Belles, Virgins and Mothers.” According to the Albany Mechanic’s Advocate, equal rights would “demoralize and degrade [women] from their high sphere and noble destiny, . . . and prove a monstrous injury to all mankind.” The New York Herald published the entire text of the Seneca Falls Declaration, calling it “amusing,” but conceding that Lucretia Mott would “make a better President than some of those who have lately tenanted the White House.” The only major paper to treat the event seriously was the liberal editor Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Greeley found the demand for equal political rights improper, yet “however unwise and mistaken the demand, it is but the assertion of a natural right and as such must be conceded.”

Stung by the public outcry, many original signers begged to have their names removed from the Declaration. “Our friends gave us the cold shoulder, and felt themselves disgraced by the whole proceeding,” complained Cady Stanton. Many women sympathized with the convention’s goals, but feared the stigma attached to attending any future meetings. “I am with you thoroughly,” said the wife of Senator William Seward, “but I am a born coward. There is nothing I dread more than Mr. Seward’s ridicule.”

But Cady Stanton saw opportunity in public criticism. “Imagine the publicity given our ideas by thus appearing in a widely circulated sheet like the Herald!” she wrote to Mott. “It will start women thinking, and men, too.” She drafted lengthy responses to every negative newspaper article and editorial, presenting the reformers’ side of the issue to the readers. Mott sensed her younger colleague’s future role. “Thou art so wedded to this cause, ” she told Cady Stanton, “that thou must expect to act as pioneer in the work.”

News of the Seneca Falls Convention spread rapidly and inspired a spate of regional women’s rights meetings. Beginning with a follow-up meeting two weeks later in Rochester, New York, all subsequent women’s rights forums featured female chairs. New England abolitionist Lucy Stone organized the first national convention, held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850. Like Cady Stanton, Stone saw the connection between black emancipation and female emancipation. When criticized for including women’s rights in her anti-slavery speeches, Stone countered: “I was a woman before I was an abolitionist–I must speak for the women.”

Quaker reformer Susan B. Anthony joined the women’s rights movement in 1852. She had heard about the Seneca Falls Convention, of course; her parents and sister had attended the 1848 Rochester meeting. Initially, however, she deemed its goals of secondary importance to temperance and anti-slavery. All that changed in 1851 when she met Cady Stanton, with whom she formed a life-long political partnership. Bound to the domestic sphere by her growing family, Cady Stanton wrote articles, speeches and letters; Anthony, who never married, traveled the country lecturing and organizing women’s rights associations. As Cady Stanton later put it, “I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them.” In time, Susan B. Anthony’s name became synonymous with women’s rights.

Women’s rights conventions were held annually until the Civil War, drawing most of their support from the abolitionist and temperance movements. After the war, feminist leaders split over the exclusion of women from legislation enfranchising black men. Abolitionists argued that it was “the Negro’s Hour,” and inclusion of female suffrage would jeopardize passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which enfranchised ex-slaves. Feeling betrayed by their old allies, Cady Stanton and Anthony opposed the Fifteenth Amendment. Their protest alienated the more cautious wing of the movement and produced two competing suffrage organizations.

In 1869, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe–well known as the author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic–and others formed the moderate American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), while Cady Stanton, Anthony, Martha Wright and the radical faction founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). Lucretia Mott, now an elderly widow, sought in vain to reconcile the two camps.

Both organizations sought political equality for women, but the more radical NWSA actively promoted issues beyond suffrage. Guided by the original Seneca Falls Resolutions, the NWSA demanded an end to all laws and practices that discriminated against women and called for divorce law reform, equal pay, access to higher education and the professions, reform of organized religion, and a total rethinking of what constituted “woman’s sphere.” Cady Stanton spoke about women’s sexuality in public, and condemned the Victorian double standard that forced wives to endure drunken, brutal and licentious husbands. Anthony countenanced–and occasionally practiced–civil disobedience; in 1872 she was arrested for illegally casting a ballot in the presidential election.

By the time the two rival organizations merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), much had been accomplished. Many states had enacted laws granting married women property rights, equal guardianship over children, and the legal standing to make contracts and bring suit. Nearly one-third of college students were female, and 19 states allowed women to vote in local school board elections. In two western territories—Wyoming and Utah—women voted on an equal basis with men. But full suffrage nationwide remained stubbornly out of reach. The NAWSA commenced a long state-by-state battle for the right to vote.

NAWSA’s first two presidents were Cady Stanton and Anthony, both now in their seventies. Old age did not mellow either one of them, especially Cady Stanton. Ever the rebel, she criticized NAWSA’s narrow-mindedness, and viewed with increasing suspicion its newly acquired pious prohibitionist allies. NAWSA’s membership should include all “types and classes, races and creeds,” and resist the evangelical infiltrators who sought to mute the larger agenda of women’s emancipation.

Cady Stanton had long advocated reform of organized religion. “The chief obstacle in the way of woman’s elevation today,” she wrote, “is the degrading position assigned her in the religion of all countries.” Whenever women tried to enlarge their “divinely ordained sphere,” the all-male clerical establishment condemned them for violating “God’s law.” Using the Scriptures to justify women’s inferior status positively galled her. In 1895, she published The Woman’s Bible, a critical commentary on the negative image of women in the Old and New Testaments. Even Anthony thought she had gone too far this time, and could do little to prevent conservative suffragists from venting their wrath. During the annual convention of NAWSA, both the book and its author were publicly censured. Henceforth, mainstream suffragists would downplay Cady Stanton’s historic role, preferring to crown Susan B. Anthony as the elder stateswoman of the movement.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902 at the age of 83, and Susan B. Anthony in 1906 at 86. By then a new generation of suffrage leaders emerged—younger, better educated, and less restricted to the domestic sphere. The now respectable middle-class leadership of NAWSA adopted a “social feminist” stance, arguing that women were, in fact, different from men, and therefore needed the vote in order to apply their special qualities to the political problems of the nation.

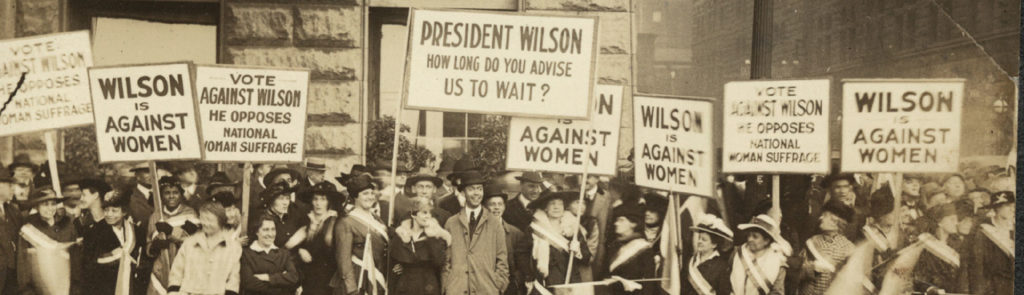

However, more militant suffragists, among them Quaker agitator Alice Paul and Cady Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Stanton Blatch, continued to insist upon women’s absolute equality. They demanded a federal suffrage amendment as a necessary first step to achieving equal rights.

Victory on the voting rights issue came in the wake of World War I. Impressed by the suffragists’ participation in the war effort, Congress passed what came to be known as the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment” in 1919. Following state ratification a year later, it enfranchised American women nationwide in the form of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

It had been 72 years since that daring call for female voting rights was issued at the Seneca Falls Convention. On November 2, 1920, 91-year-old Charlotte Woodward Pierce went to the polls in Philadelphia, the only signer of the Seneca Falls Declaration who lived long enough to cast her ballot in a presidential election.

Constance B. Rynder is a professor of history at the University of Tampa, and specializes in women’s history.

this article first appeared in American history magazine

Facebook @AmericanHistoryMag | Twitter @AmericanHistMag