What did the young newlywed Elizabeth Stanton find most fascinating on her honeymoon visit to London in 1840?

“Lucretia Mott” was Stanton’s reply.

Both women are well known champions of women’s rights in the United States, organizing in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 the first women’s rights convention. Far less familiar is how their paths crossed at the World Antislavery Convention in London in June 1840 and how that meeting, in Stanton’s recollection, put women’s rights on the national to-do list.

Mott was a whaler’s daughter and iconoclast Quaker. Stanton was a privileged, headstrong daughter of a prominent, slave-holding lawyer in New York. In her 1885 memoir, Elizabeth Cady Stanton recalled: “It is a irony of history that the world’s antislavery convention should stand as a landmark not for the freedom of the slave, but of woman.”

Lucretia Mott, headstrong Quaker

In the 1840s, Lucretia Mott was a big name among reformers, noted not for women’s rights but for her unflinching advocacy for the freedom of enslaved Blacks. She was a celebrity known for inspired off-the-cuff speaking that challenged listeners to obey their inner moral compass over dogma, stand against slavery, and boycott goods made by enslaved labor. Mobs targeted her for her speaking, and she had weathered sharp criticism for her willingness to step outside the conventions of the Quaker faith and rely more on conscience than on Quaker elders’ strictures.

Mott, 25 years older than Stanton, had grown up on Nantucket, where her father believed in women being trained in “usefulness” and where women were well known for self-reliance, having to manage households and businesses when their husbands were on long whaling voyages. Nantucket’s whaling industry attracted many free Blacks, and she had from an early age felt sympathy for enslaved Blacks.

Unfairness rankled her, including when she learned that female teachers, despite receiving the same education as male teachers, were paid half as much as men. In addition to the Quaker belief in equality of men and women, she embraced the teaching of Elias Hicks, who urged Quakers to resist blind obedience to authority, whether to Quaker elders or biblical scripture, and nurture a faith devoted to faith-based deeds, not dogma.

She was small and dainty in appearance, and at age 47, was attending the convention with her husband, James Mott. Both were American delegates to the World Antislavery Convention in London.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Elizabeth Stanton, daughter of Privilege

Twenty-five-year-old Elizabeth Stanton, newly wed on May 1, 1840, was traveling on her honeymoon with her husband Henry Stanton, an abolitionist speaker — already a friend of Lucretia Mott’s — and delegate to the London convention.

Unlike his new wife, Henry Stanton had had a rough start in life. His father had abandoned the family, and his mother, Susan Brewster Stanton, had boldly obtained a divorce, a rarity in those days, incurring excommunication from her church of 40 years. Susan’s example of self-determination likely influenced Henry Stanton’s ability to navigate the 47-year marriage he would go on to enjoy with the lively Elizabeth Stanton.

Stanton, who later incorporated her maiden name, Cady, into her full name, had had an unusually good education for a woman in her day, helped by tutoring from a neighbor in Greek, Latin, and arithmetic. She had always chafed at the restrictions women faced, and had been stung at the age of 11, by her father’s comment, upon the death of his only surviving son, Eleazar, “Oh, my daughter, I wish you had been a boy.”

She then vowed, “I will be a boy, and do all my brother did.”

That included enjoying a game of tag with her brother-in-law before boarding the ship to the London convention.

Mott and Stanton Meet in London

The American delegates sailed into London after three weeks at sea. On June 12, the convention began, and a vote was taken to exclude women from the deliberations, spurning seven female delates from the United States. The women had expected to be excluded, for reasons related in part to the American women’s allegiances within the abolitionist movement rather than to their sex alone. They had decided to attend on principle. During the convention, they were seated behind a curtain and prevented from assembling formally on their own.

Over the course of the June 12-23 convention, Stanton and Lucretia became acquainted. On one visit to the British Museum, they sat and talked for three hours while the rest of the group wandered the venue.

“I found in this new friend a woman emancipated from all faith in man-made creeds, from all fear of his denunciations,” Stanton noted in her memoir. “Nothing was too sacred for her to question, as to its rightfulness in principle and practice. It seemed to me like meeting some being from a larger planet, to find a woman who dared to question the opinion of popes, kings, synods parliaments, with the same freedom that she would criticize an editorial in the London Times.

“‘Truth for authority, not authority for truth,’ was not only the motto of her life, but it was the fixed mental habit in which she most rigidly held herself .… When I confessed to her my great enjoyment in works of fiction, dramatic performances, and dancing, and feared that from underneath that Quaker bonnet would come some platitudes on the demoralizing influence of such frivolities, she smiled and said, ‘I regard dancing a very harmless amusement;’ and added, ‘the Evangelical Alliance, that so readily passed a resolution declaring dancing a sin for a church member, tabled a resolution clearing slavery a sin for a bishop.'”

By the end of the convention, in Stanton’s recollection, the two women had vowed to organize a convention in the United States on women’s rights. Mott remembered it differently, crediting the plan to a conversation in 1841.

Over the next eight years, Stanton became the mother of several children and the family moved from Boston to Seneca Falls, where her father bought the family a rundown house. Stanton managed the renovation. Meanwhile, Mott continued her speaking activities.

Recommended for you

Birth of a Movement

In July 1848, their paths crossed again. Mott, who was often on the road, was planning to attend a Quaker meeting in Waterloo, New York, a few miles west of Seneca Falls, and spend a few weeks with her sister, Martha Coffin Wright, who lived there.

Around the tea table of a local friend, Jane Hunt, Lucretia Mott and her sister Martha, along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Mary Ann M’Clintock — all Quakers except Stanton — discussed the status of women and decided that the time to hold a convention had come. (It is a part of the Hunt family lore that Jane Hunt’s husband briefly joined in and suggested they take action rather than complaining.) That same evening, an announcement of the July 19-20 convention “to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman” was sent to the Seneca County Courier, a semi-weekly journal in whose June 14 issue it appeared. The notice highlighted that Lucretia Mott would be at a convention “called by the Women of Seneca County, New York.”

The organizers decided to present a statement on women’s rights, and they collectively scoured historical documents and constitutions for models. Finally settling on the Declaration of Independence, they crafted a statement that borrowed generously from the document in stating their grievances and lack of representation.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights: that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness …. The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man towards woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her to prove this let facts be submitted to a candid world.”

The statement and resolutions, titled the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, listed the injuries: Women were not allowed to vote, although their property was taxed, and they were thus denied representation in government. Women were bound to obey laws they had no role in forming. They were excluded from colleges and all but a handful of occupations. Married women became civilly dead: They could not own property or enter contracts, and they could not freely divorce. Men were assumed to have intellectual superiority, while women were recognized for moral superiority — yet had no role in governance. In personal affairs, women were unfairly treated, with severe penalties for women for activities that were either ignored or lightly penalized when men did them.

Stanton’s husband Henry had helped her locate laws injurious to women, and a book of state laws was kept on hand to consult during the convention. Stanton, daughter and wife to lawyers, later recalled that “if there ever was to be an improved status of woman, its basis must be laid in the law of the land; in other words, that the political safeguards of the two sexes should be identical. This was a claim which had not, in our generation, been made either by women or for women.“

Differing Goals

For Stanton, voting rights were paramount. Denied the right to vote, women were taxed without representation and could not consent to governance. Stanton insisted on adding a demand for the right to vote in the convention resolutions.

Mott, along with many others, initially opposed including women’s right to vote as too dramatic.

“Thou wilt make the convention ridiculous,” she demurred.

Stanton’s father, Judge Daniel Cady, was apparently so alarmed by the proposition that he headed for Seneca Falls to check if her “brilliant brain had been turned.” The two talked for hours into the night, and Cary told Elizabeth that he wished she “had waited till [he] was under the sod before [she] had done this foolish thing.”

It was in her father’s law office, however, that Stanton had first become aware of the low status of women while listening to his clients.

“In my earliest girlhood I spent much time in my father’s office,” she once recalled. “There, before I could understand much of the talk of the older people, I heard many sad complaints, made by women, against the injustice of the laws. We lived in a Scotch neighborhood, where many of the men still retained the old feudal ideas of women and property. Thus, at a man’s death, he might will his property to his eldest son; and the mother would be left with nothing in her own right. It was not unusual, therefore, for the mother — who had perhaps brought all the property into the family — to be made an unhappy dependent on the bounty of a dissipated son.”

Hasty Convention

The convention plan went forward — so hastily arranged that the organizers had failed to get the key to open the Wesleyan Chapel and Stanton’s young nephew had to crawl through a window to open the front doors. The short notice, and the small town location, probably helped the convention avoid the attention visited on similar events, such as the mob attack in 1843 that burned to the ground Pennsylvania Hall — an impressive building purposefully constructed in 1838 as a “Temple of Free Discussion” for housing events opposing slavery and “other evils” — during an event where Lucretia Mott and others were speakers. The Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls was also built in the service of reform. Constructed in 1843, it was a hub for meetings of a faction of Methodists that often included women and Blacks on their boards.

Although the notice had stated that only women would be allowed to attend, some 40 men showed up, and the organizers let them in. Roughly 300 people attended in all. Stanton and Mott took turns speaking before presenting the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments and opening the meeting to discussion.

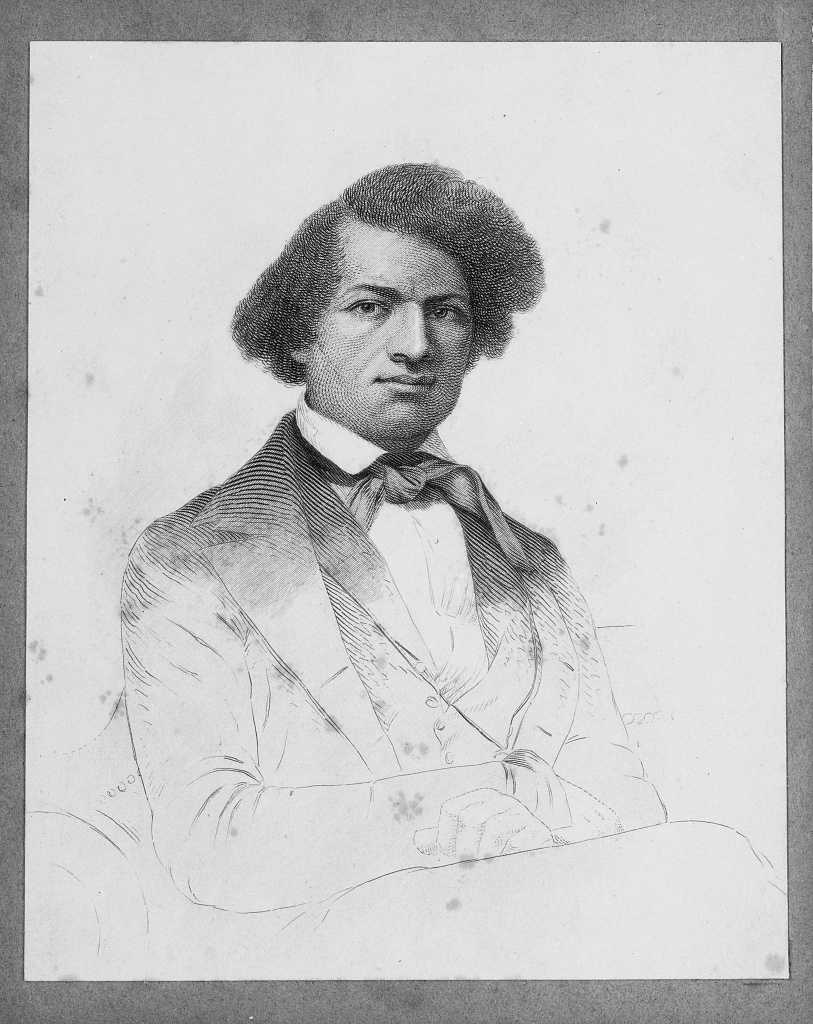

Even more people attended the second day and discussion continued, including opposition to the goal of women’s suffrage. Famed abolitionist orator Frederick Douglass, also head of the Rochester-based newspaper North Star, spoke in support of the resolution demanding women’s right to vote, which then passed.

After adoption of the Declaration and its resolutions, 68 women and 32 women, including Douglass, signed the document. When word of the convention got out further afield, a torrent of criticism followed. Stanton, however, wasn’t bothered by criticism, later saying you don’t need to state what people already accept.

Stanton Befriends Susan B. Anthony

Similar conventions were organized in other towns and cities. Three years later, at a women’s rights convention in Rochester, Stanton met Susan B. Anthony, when reformer Amelia Bloomer introduced the two.

The consequences of this meeting would ripple for decades. Although Mott had inspired Stanton and helped spell out the inequality women endured, she hadn’t Stanton’s unflagging passion for the cause. In 1866, amid the fight over whether women and Blacks should both be accorded rights under constitutional amendments after the Civil War, Mott, then 73, confided, “This Equal Rights Movement is Play — but I cannot enter into it! Just hearing their talk and the reading made me ache all over, and glad to come away and lie on the sofa here to rest ….”

The figure that would sustain Stanton over the next five decades was, like Mott, a Quaker. Susan B. Anthony and Stanton would live through an enduring schism in the women’s rights movement after the Civil War ended. Women who had supported the fight to free enslaved Blacks had eagerly anticipated new freedoms for themselves as well. But provisions in the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, passed by Congress and ratified 1869-1870, guaranteed voting rights to Black men, not women.

The Suffragists Split over the Black Vote

Stanton, Anthony, Mott and others were furious, and the split in the movement over enfranchisement of Black men in advance of women persisted for several decades. Stanton and others resented electoral power being handed to men mostly less literate and educated than themselves.

Stanton and Anthony were so alienated that they founded the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869 — splitting from the American Equal Rights Association — and accepted support for their campaign and newspaper, Revolution, from wealthy entrepreneur George Francis Train, whose openly racist positions alienated longstanding allies. The newspaper’s masthead stated: “Justice, Not Favors: Men Their Rights and Nothing More — Women Her Rights and Nothing Less”). The rival American Woman Suffrage Association focused on obtaining the vote for women and working at the state level, while Stanton and Anthony pursued a more wide-ranging vision of equal rights for women nationally.

Reuniting for Women’s Rights

The split in the women’s rights movement over the priorities and strategy remained for decades. In 1888, however, the National Woman Suffrage Association hosted the International Council of Women, a commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the landmark convention in Seneca Falls, in Washington, D.C. Anthony, a tireless campaigner, gathered surviving signers of the Declaration — 36 women and eight men. She had to goad Stanton — who was then in England — into attending and writing a speech for the event. Representatives from abroad reported on women’s rights, and a portrait of Lucretia Mott, who died in 1880, hung above the stage. The gathering proved an opportunity for the two American factions to resolve differences and merge. In 1889, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was established. The first NAWSA convention met in February 1890.

The Stanton-Anthony partnership lasted to the end of their lives, even over the uproar over Stanton’s “The Woman’s Bible,” published in segments from 1895 to 1898. In this work, Stanton and others combed through the Bible, annotating passages referring to women and noting inconsistencies in a lawyer-like fashion.

“Women are told that they are indebted to the Bible for all the advantages and opportunities of life that they enjoy to-day,” Stanton wrote, “hence they reverence the very book that above all others, contains the most degrading ideas of sex.”

“The Woman’s Bible” affronted both men and women. Anthony hadn’t participated in the effort, but she defended Stanton’s right to publish nonetheless.

Lucretia Mott may have been midwife to the women’s rights movement, but Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were its most prominent and unflagging warriors.

“[W]henever I saw that stately Quaker girl coming across my lawn, I knew that some happy convocation of the sons of Adam was to be set by the ears, by one of our appeals or resolutions,” Stanton fondly recalled. “I forged the thunderbolts, and Susan would fire them.”

Posthumous Victory

The 19th constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, and ratified on Aug. 18, 1920. The text read: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The amendment passed 40 years after the death of Lucretia Mott in 1880; 18 years after the death of Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1902, and 14 years after the death of Susan B. Anthony in 1906. The only living activist dating from the early suffrage movement to celebrate the passage was 96-year old Antoinette Brown Blackwell.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.