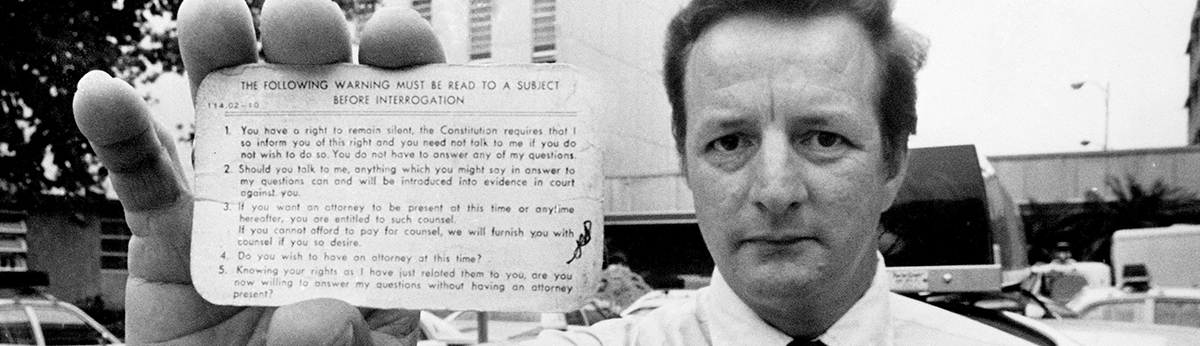

So familiar is the mantra that TV viewers can chant along with any actor playing a cop taking a suspect into custody: “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.”

Real officers routinely give that warning. They did not always.

Who was Miranda?

The story of that change began on Wednesday, March 13, 1963, when police in Phoenix, Arizona, brought in Ernesto Miranda for questioning. Ten days earlier, a man had abducted and raped a learning-disabled 18-year-old. The woman had been on her way home after closing the concession stand at the movie theater where she worked.

Recommended for you

Officers had a convincing case. Miranda, 23, had a criminal record, including convictions for minor crimes and an arrest for rape. His features closely fit the description the victim had given of her assailant shortly after the attack. In a lineup, she pointed out Miranda as the participant who looked most like her attacker. A green Packard owned by the woman Miranda was living with had distinctive interior features the victim mentioned in describing the automobile in which her attacker abducted her. And Miranda’s employer said that on the night of the attack the accused had not shown up for work.

Phoenix police wanted to strengthen their case by getting Miranda to confess. After two hours of questioning, he did. All sides agree that those two hours involved no blatant coercion or brutality—although the police did convey that the victim had been more certain in identifying Miranda in the lineup than she actually had been.

Miranda wrote out his confession. Police took him to see the victim to make a voice identification. The woman affirmed that his voice matched her attacker’s. Asked by police if she was the woman he referred to in his confession, Miranda answered, “That’s the girl.”

Lawyer Alvin Moore, appointed to defend Miranda, tried to get his confession excluded from evidence. Moore said Miranda had made the confession without fully understanding his right not to confess. That got nowhere with the judge, mainly because each sheet on which Miranda had written his confession bore the heading: “This statement had been made voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion or promises of immunity and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding that any statement I make can and will be used against me.” And the officer running the interrogation testified that he had read the heading aloud to Miranda before the suspect began writing.

A court convicted Miranda and sentenced him to 20 years, minimum. The Supreme Court of Arizona affirmed the verdict, rejecting Moore’s claim that Miranda’s confession was faulty because police had not told him he could have a lawyer present at the interrogation. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

What is an admissible confession?

Moore’s argument very much reflected the tenor of the times in criminal defense law. When the justices agreed to review Miranda v. Arizona, they combined that case with three convictions appealed on similar grounds: a New York state robbery case, a federal case involving two robberies in California, and a California case involving a purse snatching in which the victim died. The California Supreme Court had thrown out the purse-snatching conviction because police had not advised the accused of his right to counsel, but in the other two cases appellate courts had upheld convictions. After hearing a total of three days of arguments in the four cases in February-March 1966, the high court issued a single combined opinion, headed by Miranda’s name.

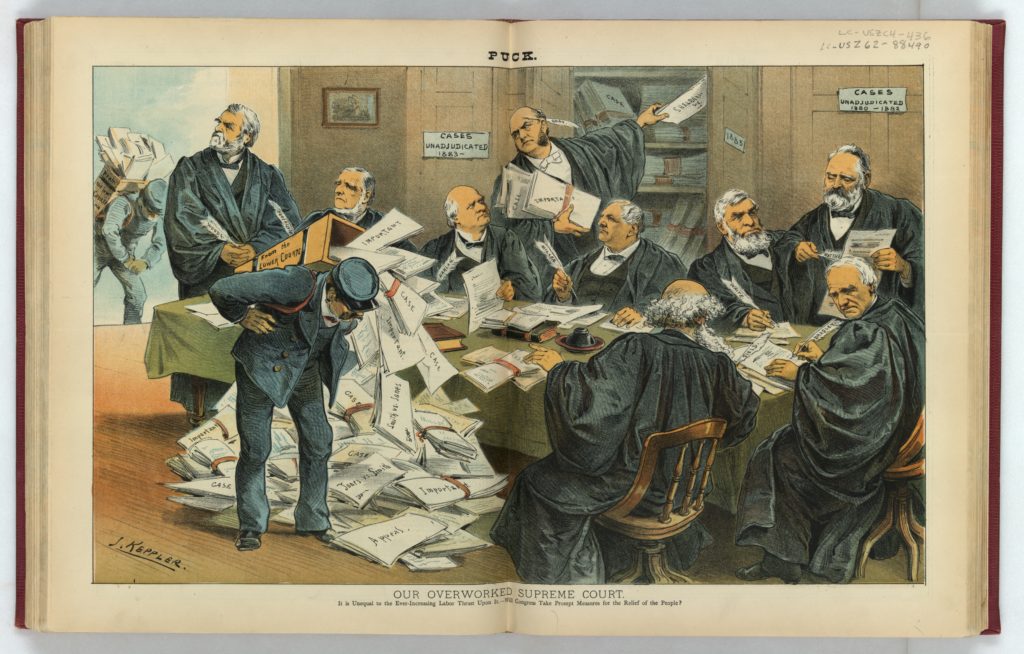

In preceding years, justices had been struggling to define when a confession’s circumstances were so questionable that the statement could not be presented to a jury. Under the English common law that had prevailed in the United States since the nation’s founding, a confession resulting from undue police coercion had to be thrown out. But undue coercion had no firm definition. Judges were to look at the “totality of the circumstances.”

The justices battled among themselves whether to maintain the case-by-case approach. In 1963, the justices by a 5-4 vote had ruled it incorrect to admit into evidence a confession signed by a man arrested for robbing a gas station after police refused the suspect’s request beforehand to phone his wife or his attorney. In 1964, also 5-4, the justices had nixed a confession by a man questioned in his brother-in-law’s murder—not only had police not allowed the suspect to see his lawyer, officers had not informed the suspect of his right to remain silent, which for the first time the court deemed “an absolute right.”

Those votes indicated growing concern on the part of a five-justice bloc about methods used to get confessions. The decisions prescribed no absolute rules because each case involved questionable police behavior. In the purse-snatching fatality, police quizzed the suspect for more than 14 hours before he confessed. The beauty of Miranda and associated cases to the court majority was that none bespoke a hint of police misbehavior, offering a clear opportunity to set minimum standards on making sure suspects knew their rights.

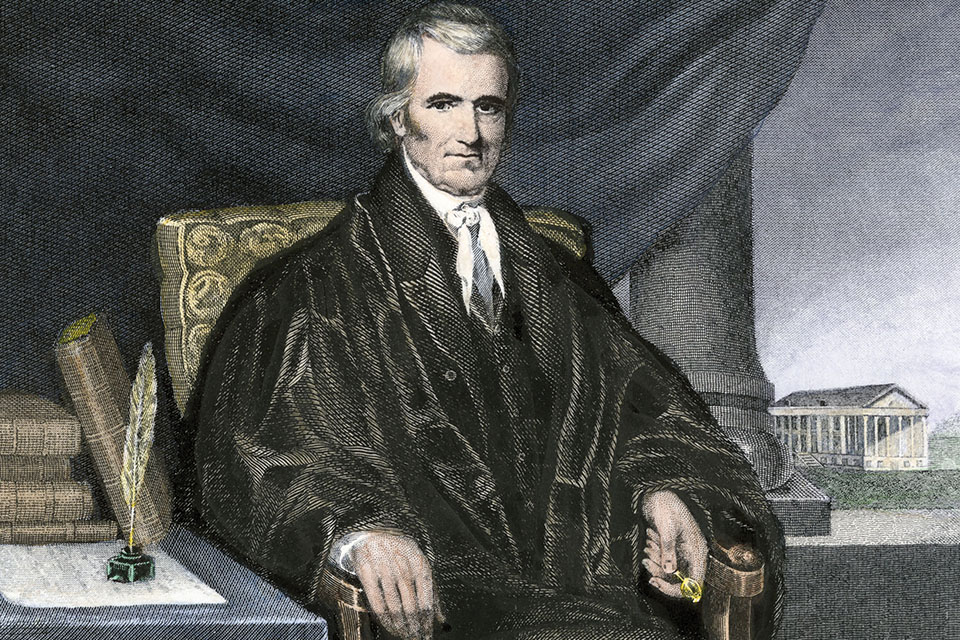

Warren’s compromise

Chief Justice Earl Warren, in earlier days a tough prosecutor, opened the justices’ conference after oral arguments on the Miranda cases by saying he believed it time to junk the “totality of circumstances” yardstick. Warren said the court should declare that to be admissible at trial a confession had to be preceded by a suspect’s being told of his right to remain silent and to have a lawyer. Warren wrote essentially the same on behalf of the five-justice majority whose members had thrown out confessions in the earlier cases.

The four dissenters said their colleagues were sending the country down a dangerous path. Justice Byron White warned that “the Court’s rule will return a killer, a rapist, or other criminal to the streets.”

Congress seconded White. In 1968, the House and Senate passed a law ordering federal trial judges to admit any voluntary confession, whether or not the suspect got a Miranda warning. That measure was so constitutionally suspect prosecutors seldom invoked it. Not until 2000 did justices have a chance to decide if Congress really could overturn Miranda. By a 7-2 vote, justices found that Congress had no such authority, and that Miranda remained the law of the land.

Moreover, said conservative Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who chose to write the opinion himself, “Miranda has become embedded in routine police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture.”

Police had learned to live with Miranda, even to appreciate having a definite rule on what to say to suspects before interrogating them—a rule that, adhered to, immunized police behavior during interrogations from scrutiny at trial.

Did Miranda go to prison anyway?

Miranda certainly didn’t inhibit Miranda’s prosecutors, who retried him, leaving out his confession. Again, he was convicted and sentenced to at least 20 years’ incarceration.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.