The Constitution’s press freedom guarantor forbids gag laws

Prior restrain of publication is unconstitutional

In American courts, litigation, even if it tests important issues of governmental powers or political philosophies, cannot trade in hypotheticals, but must present real controversies between real people. Hence, legal strategists’ efforts to find the most attractive litigants they can. It didn’t work out that way in a 1931 U.S. Supreme Court case on the freedom of the press that legal scholar Eberhard P. Deutsch called “the most important decision rendered since the adoption of the First Amendment.”

Near v. Minnesota established two legal points that are still bulwarks of journalistic liberty in the United States: that the First Amendment guarantee of press freedom applies not just to the federal government but to states as well, and that courts may not issue orders stopping publication of questionable material. This outcome was a nail-biter, because the newspaper under attack was a scandal sheet adrip with repulsive material.

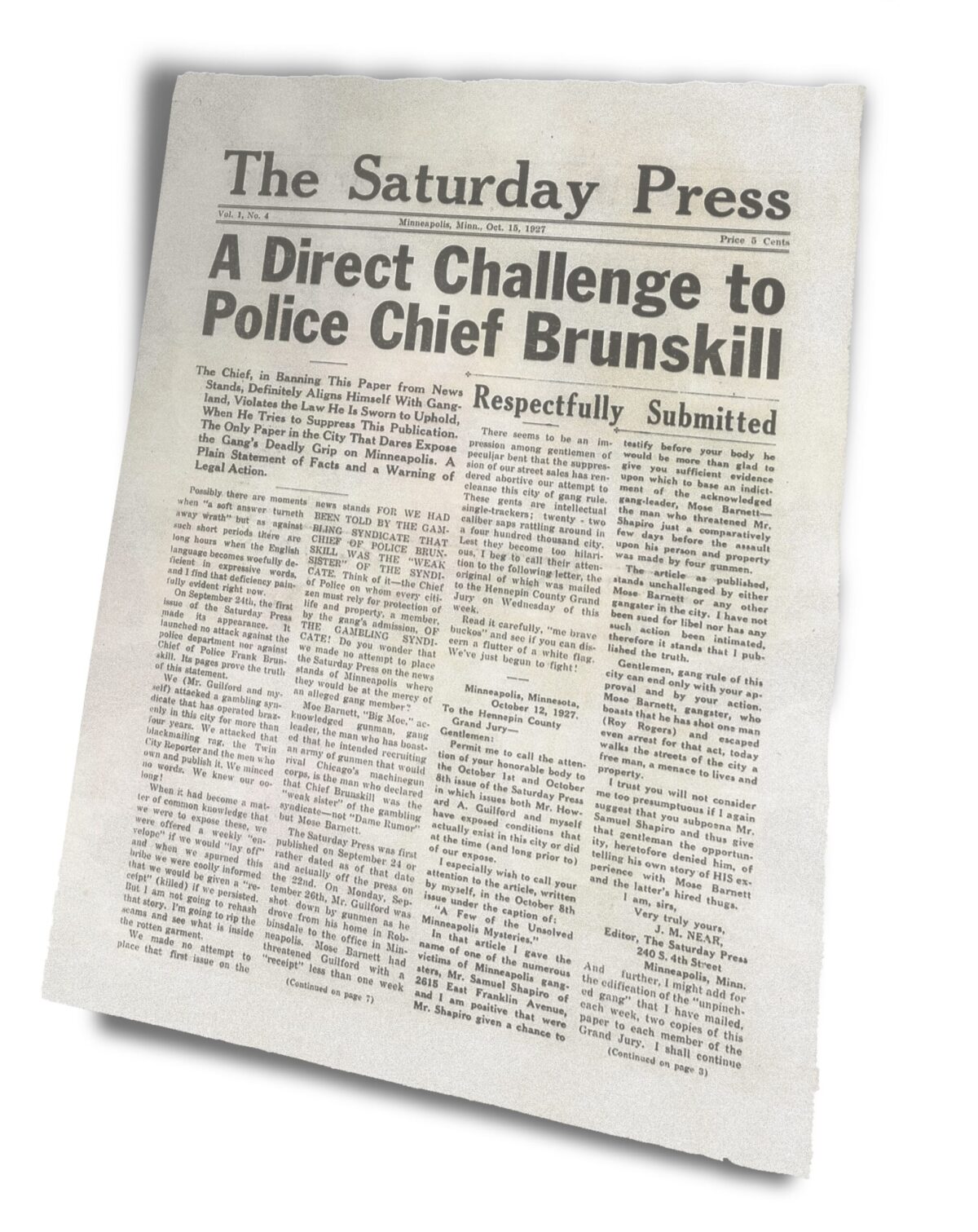

Saturday Press, a Minneapolis weekly, was one of hundreds of its ilk nationwide that in the 1920s traded in sensationalism, filling columns with a mishmash of pioneering exposes of public corruption and totally unsubstantiated calumny. Saturday Press owners Jay M. Near and Howard A. Guilford spiced their paper’s version of that stew with their own dislike of Catholics and a virulent strain of anti-Semitism. “They were scumbag editors,” says Donald M. Gillmor, professor of media ethics at the University of Minnesota, “morally wrong in their hateful prejudices.”

In 1925, two years before Near and Guilford launched their venture, the Minnesota legislature had passed the Public Nuisance Law, or Gag Act. The Gag Act authorized anyone offended by a publication to go to a judge and show that the material in question was “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” or “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory.” If the judge agreed, he could put a permanent stop to further editions. There were no provisions for a jury to participate in the proceeding. The statute, unlike anything else on the books anywhere in the United States, had been pushed by a state senator who felt a local scandal sheet, the Rip-Saw, had wronged him. Enough colleagues had felt gossipmongers’ sting that the measure unanimously passed the state Senate and the lower house 88-to-22. Duluth Mayor George Leach immediately invoked the law, seeking a permanent injunction against the Rip-Saw, but before that case could go to trial the paper’s owner died and the Rip-Saw ceased publication.

The Gag Law languished for two years until it was dusted off to whack at the Saturday Press. Hennepin County District Attorney Floyd B. Olson—later a three-term Minnesota governor—invoked the Gag Law to try to throttle the paper on the basis of its relentless condemnation of him and the Minneapolis mayor and police chief. Without giving Near or Guilford a chance to appear in court, Judge Matthias Baldwin ordered they immediately cease publication. At a hearing 10 weeks later to determine whether to make Baldwin’s temporary order permanent, the newspaper owners’ lawyer did not question the disputed articles’ loathsomeness, but instead called the Gag Law itself unconstitutional.

Baldwin found no merit in that argument. Neither did the Minnesota Supreme Court when Near and Guilford appealed the ruling against them. Government has authority to stamp out public nuisances such as whorehouses, the justices reasoned, lumping into that category a scandal sheet that “annoys, injures and endangers the comfort and repose of a considerable number of persons.”

A section of the Minnesota state constitution guarantees freedom of the press, but the justices found that guarantee to be “a shield for the honest, careful and conscientious press,” not a “defamer and scandalmonger.”

The case went back to the trial court, where Baldwin extended his original order by banning Near and Guilford from ever publishing a similar periodical. After the state Supreme Court endorsed his ruling, the case was ripe to go to the U.S. Supreme Court. Guilford had dropped out and the state of Minnesota had assumed control of the defense of the Gag Law. But Near had picked up an important ally. Much of the mainstream press saw scandal sheets as sullying the reputation of all journalism and had no problem with the Gag Law—officials at major Minnesota dailies actually helped draft the measure—but Chicago Tribune publisher Robert R. McCormick realized any publication stood at risk of being pilloried under it. McCormick threw his considerable resources into Near’s defense at the high court.

When the case was argued in January 1930, the justices were struggling to parse the relationship between the Bill of Rights and the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified 62 years earlier. The Bill of Rights itself applied only to the federal government, not individual state actions. But the 14th Amendment bars states from taking anyone’s “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” To what extent was a Bill of Rights violation also denial of due process?

Five years earlier, the court had upheld New York State’s prosecution of a socialist for publishing a manifesto interpreted as calling for violent overthrow of the U.S. government. The ruling said that the court “assumes” that the 14th Amendment protects freedom of the press from state action but did not discuss that matter or actually rule on the question.

And the decision did not stand as a strong curb against government interference with the press since the court reasoned that whether or not the 14th Amendment provided a means of measuring the constitutionality of New York’s action, prosecution was justified because the publication in the case posed a clear, immediate danger to society.

Near gave the justices a clear opportunity to consider the relationship between the First Amendment and the power granted individual states. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes drafted a ringing endorsement of the importance of freedom of the press in a democracy to ensure that the people know what is going on in their government—even when writers go too far. Hughes quoted the First Amendment’s principal author, James Madison: “[I]t is better to leave a few of its noxious branches to their luxuriant growth than, by pruning them away, to injure the vigour of those yielding the proper fruits.” The Near stance that courts cannot impose “prior restraint”—cannot prohibit publication—has remained, as Chief Justice Warren E. Burger once noted of the decision, a reinforcement of “one of the basic liberties upon which our constitutional democracy was founded.”

The court wasn’t giving the press a blank check. Parties injured by falsehoods could bring defamation suits, Hughes noted. And he acknowledged exceptions to the ban on pre-publication censorship—troop movements during wartime, for instance—but made clear that these are few and far between. What matters is the decision’s general prohibition against government stopping anyone with a press from getting out their news and views.

But the ruling was a close thing. The 5-4 vote hinged on how unattractive Jay Near and his rag were as avatars of press freedom. To the four justices who would have OK’d the Minnesota Gag Law, the case wasn’t about the role of a free press in a democracy, but about what Justice Pierce Butler, writing for the dissenters, derided as “malicious, scandalous and defamatory periodicals.” The dissenters did not see the case in terms of applying the Gag Law to more righteous publications. Butler, however, did see the long shadow, fuming that “it gives freedom of the press a meaning and a scope not heretofore recognized.”