It is said that old soldiers never die. In the case of Samuel Whittemore, he refused to fade away.

Capt. Whittemore was a 78-year-old farmer living on the outskirts of Concord, Massachusetts when on April 19, 1775, he awoke to the sound of marching British troops and the “shot heard round the world.”

According to an 1864 account by Minister Samuel Abbot Smith, Whittemore’s wife, Esther, began packing up their home so she and her husband could wait out the imminent violence at her stepson’s home.

She assumed her aging husband, a former member of the British Royal dragoons, would accompany her. Instead, according to Smith, Whittemore was found “oiling his musket and pistols, and sharpening his sword.”

“Often… (colonists) acted simply as guerilla fighters, whenever they felt like it,’’ author Arthur B. Tourtellot in “Lexington and Concord” wrote, “and unquestionably took part in the very early fighting of the war.’’

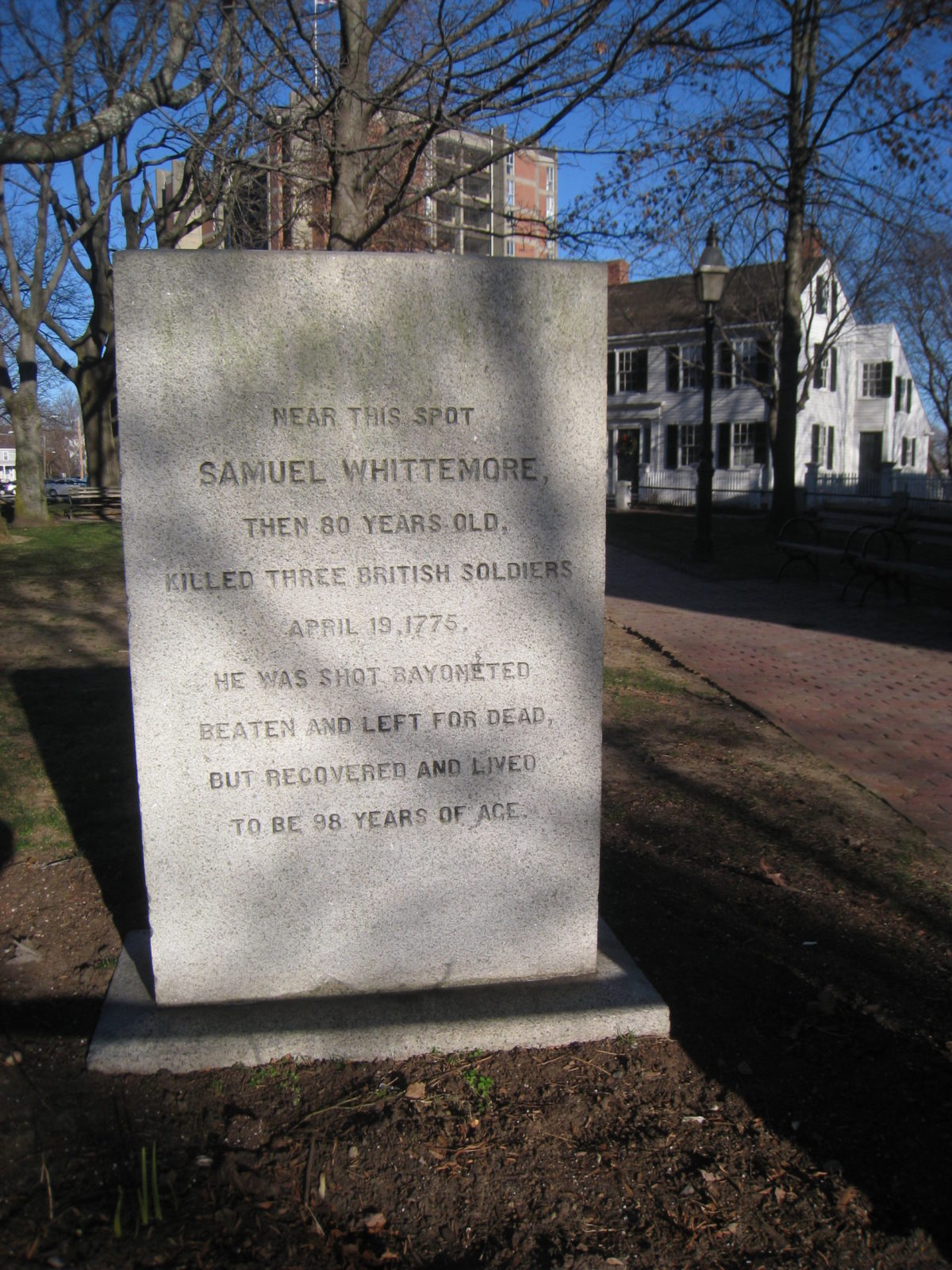

As the British retreated to Boston through the Whittemores’ town of Menotomy on April 19, the aging dragoon was determined to eke out his pound of flesh on the British. Crouching behind a wall near his home, the farmer shot two soldiers to death and possibly killed one more, according to the Journal of the American Revolution.

British soldiers quickly tracked down the less-than-mobile guerilla soldier and enacted a savage revenge.

Whittemore was shot in the face at point-blank range, bayoneted no less than six times and clubbed in the head with the butts of the British soldiers’ muskets.

Left for dead, Whittemore again lived up to the old soldier’s motto and refused to die — an act the Journal of the American Revolution called an “epic demonstration of New England stubbornness.”

He lived another 18 years.

Villagers brought Whittemore to a nearby tavern, and a doctor — albeit believing it futile — dressed the some 14 wounds.

According to Boston.com, genealogy of the Whittemore family, written by Bernard Bemis Whittemore, claims the senior soldier recovered “in about four hours,’’ but another Whittemore family account, as relayed in the Benjamin and William Richard Cutter history, says it took a few weeks before he could “recognize his family.’’

At this point, he was asked if he regretted his actions.

“No,’’ he said. “I should do just so again.’’

Whittemore’s heroics that day became part of state lore, and in 2005, he was officially proclaimed the hero of Massachusetts.

Yet Whittemore’s devotion to the cause of American independence far predated the historic events of April 19, 1775.

Seven years earlier, the town of Cambridge (which Menotomy was a part of) elected Whittemore to a committee to fight the Stamp Act. That same year, writes the New England Historical Society, Cambridge voters elected him as a delegate to the Massachusetts Committee of Convention, which objected to Parliament’s revenue acts and the quartering of troops in Boston.

Later, in 1772 — less than three years before the farmer lost his cheekbone to a musket ball — the then-76-year-old Whittemore was again elected to the town’s Committee of Correspondence. The committee fervently objected to the Tea Act.

“Rather than one discrete act, Whittemore’s heroic stand was a single point in a continuum of action,” writes the Journal of American History.

The tales of Whittemore’s heroics and “uncommon longevity” have long endured, and in the end, it was the old soldier who had the last laugh. Whittemore died at the age of 96 on February 2, 1793 — long enough, according to his obituary, “to see the complete overthrow of his enemies, and his country enjoy all the blessings of peace and independence.’’

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.