The relationship between Great Britain and the American province of Massachusetts Bay deteriorated rapidly during the late winter and spring of 1775. On April 14 Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, the commander of British forces in North America, received orders from London to disarm colonial militias and arrest rebel leaders. British intelligence had learned the Massachusetts militia was stockpiling weapons and supplies in Concord, 16 miles west of Boston. On April 18 Gage ordered a task force to march on Concord “with the utmost expedition and secrecy” to capture and destroy the military stores.

Gage entrusted the Concord mission to Lt. Col. Francis Smith, commander of the 10th Regiment of Foot. Instead of assigning the mission to complete regiments, Gage created a task force, selecting light infantry and grenadier companies from the regiments under his command and the 1st Battalion of Royal Marines. The 21 companies totaled more than 700 men. Major John Pitcairn of the Royal Marines was Smith’s second-in-command. There was no intermediate level of command between them and the 21 companies. Gage’s use of only elite troops in the unorthodox task force was an indication of the mission’s importance.

In 1775 a British infantry regiment comprised one company of grenadiers, one company of light infantry and eight battalion companies. The grenadiers and light infantry were the elite troops. The period London Encyclopedia called the grenadiers “the tallest and stoutest men, consequently the first upon all attacks.” These shock troops were used for breaching obstacles and other heavy work. In combat grenadiers operated on the regiment’s right. Light infantrymen acted as flankers and protected the left of the formation.

British troops in colonial North America carried the Model 1756 long land pattern “Brown Bess” musket. The .75-caliber smoothbore fired a .69-caliber ball with a maximum effective range of about 100 yards. In Boston, the Redcoats bound for Concord received 36 rounds of ammunition—then the basic load for a British infantryman. They would receive no resupply on the march. The Redcoats also carried bayonets, giving them a huge advantage over the Patriot militia in close-quarters fighting.

Massachusetts law required all able-bodied men aged 16 to 60 to join their local militias. Many of their officers were veterans of British campaigns against the French and Indians. The colonial government also urged each town to organize a third of its militia into companies of “minutemen,” composed primarily of younger men, who received extra training and committed to turn out immediately in an emergency. That said, most of the Patriots who would confront the British during their retreat from Concord were regular militiamen. Furthermore, though towns purchased weapons and ammunition, most militiamen fought with their personal muskets, shot and powder. Few owned bayonets.

Militia weapons included a range of locally crafted hunting and military designs, commercial arms contracted from private makers, firearms drawn from provincial arsenals, confiscated Loyalist arms, state purchases of spare guns from civilians, surplus arms from European dealers and muskets issued in North America by the British during earlier conflicts.

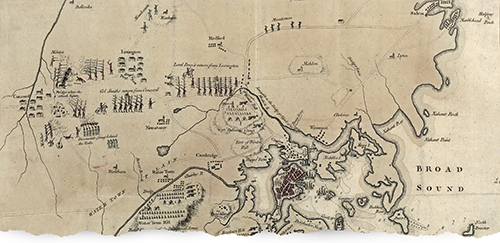

The Patriots learned of Smith’s mission to Concord on April 18 and sent dispatch riders (including the celebrated Paul Revere) to alert area townships the British were coming. Militiamen from across the region began assembling in their home villages, including Concord. The Redcoats began marching west from Cambridge, across the Charles River from Boston proper, at about 2 a.m. on April 19. By 5 a.m. the column had reached Lexington, some 7 miles shy of Concord, where they skirmished with the local militia, spilling the first blood of the American Revolutionary War.

The British arrived in Concord around 7 a.m. When the Redcoats marched into town, the militia retreated to the outskirts. Smith then dispatched detachments of soldiers to seize the cached military stores. He sent one group of soldiers 2 miles north of town to search the farm of Colonel James Barrett, the local militia commander. After searching the village, British soldiers smashed up and torched several cannon carriages. Enraged at the sight of smoke rising from the center of town, militiamen from Concord, Acton, Lincoln, Bedford, Carlisle, Chelmsford, Groton, Littleton, Stow and Westford—some 500 men in all—confronted Redcoats guarding the North Bridge over the Concord River near Barrett’s farm. The British fired a volley as the Patriots approached. The militiamen returned fire, killing several Redcoats and wounding many others, in an action memorialized as the “shot heard round the world.” The bloodied British withdrew to Concord.

After the fight at North Bridge the Redcoats tarried in Concord several more hours. They destroyed a cache of confiscated military supplies, consolidated their scattered forces and organized transportation for their wounded. Smith showed no sense of urgency. That would prove a mistake, for while the British lingered, militiamen spread word and converged on Concord.

Finally, around noon, after having dallied five hours in Concord, the British force began its return trek to Boston. At the outset of the march Smith took the precaution of deploying 80 to 100 flankers on a ridge to the left, or north, side of Bay Road, the outbound route. The main column marched unmolested for about a mile to a junction known locally as Meriam’s Corner. At that point Bedford Road came down from the north to join Bay Road. Just past the intersection Bay Road crossed Mill Brook. Although only a trickle today, in 1775 it was a flowing stream that required a bridge to traverse. The ridge ended just shy of Bedford Road, so as the Redcoats approached the bridge, Smith ordered the flankers to rejoin the main body to cross Mill Brook.

Smith showed no sense of urgency. That would prove a mistake, for while the British lingered, militiamen spread word and converged on Concord

About the time the British started across the bridge, Patriot militia began converging at Meriam’s Corner. From the north fresh companies arrived from Reading, Billerica and Bedford. The militiamen who had fought at North Bridge marched across open pasture known as the Great Meadow, north of Concord. As Smith’s flankers rejoined the main column, Patriots took up positions around the home and outbuildings of Nathan Meriam, within 100 yards of Bay Road. Six small militia companies from Sudbury watched the British from a respectful distance across open fields south of the road.

As the last of the British forces crossed Mill Brook, the rear guard turned and fired a wild volley to drive off approaching militia. That was all the excuse the Patriots needed. From either side of Bay Road they unleashed a volley at the retreating Redcoats. When the smoke cleared, two British soldiers lay dead and several others were injured. “Up to this moment the remainder of the day might have passed without further incident,” a history of that fateful day noted. “The few minutes of action at Lexington Green and Concord Bridge might even have been written off as part of a chronicle without any fulfillment or far-reaching end. Such however, was not destined to be the case.…From this volley there was to be no point of return.”

As the British force continued to retreat east on Bay Road, militiamen shadowed their march and sniped at the Redcoats from both sides of the thoroughfare. Once over Mill Brook, Smith redeployed his flankers—which helped keep the Patriots from approaching too closely—and inflicted casualties among the militia. Less than a mile past Meriam’s Corner the British column reached Brooks Hill (aka Hardy’s Hill), where waiting militiamen had flanked the road. Wooded terrain and buildings on the Brooks farm and at Brooks Tavern offered concealed positions, allowing the Patriots to lay down accurate fire on the Redcoats from close range. Although the British quickly pushed through the hail of musket fire with their flankers’ help, the worst was yet to come.

The village of Woburn lies some 4 miles northeast of Lexington. At about 1 a.m. on April 19 a lone horseman had ridden through to alert officials the British were marching out from Boston, and the Woburn Militia immediately began assembling. “The town turned out extraordinary,” recalled Maj. Loammi Baldwin, the local commander, “and proceeded toward Lexington.” Down dirt roads and across country Baldwin and three companies of Woburn Militia, totaling some 250 men, made their way south. Although they heard “a great firing” from the direction of Lexington, the Woburn men were too late to make a stand with their neighbors on the green. When they did arrive, they were infuriated to find “eight or 10 dead.”

Baldwin ordered his men to trail the British to Concord. Some 4 miles west of Lexington they reached Tanner’s Brook, a stream cutting across Bay Road, where the men refreshed themselves. Before moving on, they heard the fighting on Brooks Hill and soon spotted approaching Redcoats. The Woburn Militia, in Baldwin’s recollection, “then concluded to scatter and make use of the trees and walls for to defend us and attack them.” Dashing uphill to a sharp northeastward bend in Bay Road, they took up positions in an apple orchard overlooking the road.

The half-mile of Bay Road between the two bends—the Bloody Angle—offered ideal cover and concealment for an ambush

From Brooks Hill the British line of march dipped into the narrow ravine drained by Tanner’s Brook. From there the road climbed some 100 yards before reaching a bend to the left, or northeast—the first of two turns. Beyond the first bend the road climbed sharply and then leveled off as it approached the second bend. To the left, or west, side of the road was open pasture dotted with large trees. The apple orchard stood to the right of the first bend, while a woodlot filled with younger trees flanked the second. The half-mile of Bay Road between the two bends—the Bloody Angle—offered ideal cover and concealment for an ambush.

Exploiting their familiarity with the terrain and local roads, the Patriots converged on the stretch of Bay Road between the bends ahead of the Redcoats. Before reaching the Bloody Angle, the British had the advantage of interior lines, forcing the Patriots to move farther and faster to maintain contact with the Redcoat column. After the skirmish at Brooks Hill, however, some militiamen cut cross-country to Bay Road beyond the first bend, allowing them to reach the wooded pasture ahead of the Redcoats—a classic example of the use of interior lines. Other militiamen who had fought at Meriam’s Corner marched cross-country through an open area known as the Great Fields before scaling a wooded height to reach Bay Road and take up firing positions in the wooded pasture near the second bend. A third group of Patriots dogged the Redcoats from the rear. Though popular lore avows each man fought on his own, in reality the militia moved as companies, each under its commander’s control. “Far from being a disorganized rabble,” historian Walter Borneman wrote, “the rebels were working together with deadly efficiency.” The British were about to march into a half-mile-long gauntlet of fire.

After passing the ambush on Brooks Hill, the Redcoats marched quickly down the east face of the rise to escape. It was 1:30 p.m.

Militiamen from Westford, Stow and Groton, who had just arrived from their homes west of Concord, harassed the rear of the column. At the bottom of the hill Lincoln Bridge spanned Tanner’s Brook, where the restrictive terrain again forced Smith to recall his flankers to cross the stream. Once past Lincoln Bridge the weary Redcoats trudged uphill some 100 yards to the first bend. Capt. Lawrence Parsons’ light company of the 10th Foot was in the lead. Parsons was the only officer in his company who remained uninjured. As they rounded the bend, the British met a blast of musket fire from Woburn militiamen concealed in the apple orchard and behind stone walls. After firing, the Woburn men raced into the adjacent woodlot to keep the British column under constant fire.

After the Woburn Militia opened up on the right flank of the British column, Patriots across the road took their turn. There, concealed behind large trees in the wooded pasture, militiamen from Reading, Redford, Chelmsford, Billerica and others who had engaged the enemy at Brooks Hill fired on the exhausted Redcoats. Smith detached flankers to drive back the Patriots, but they were not as effective at engaging militiamen hiding behind large trees as they had been in the more open landscape closer to Concord. The trees provided good cover, and the flankers merely became better targets the closer they came to the concealed militiamen.

The Redcoats had entered Bloody Angle as an organized military formation and emerged a bloodied mob. It is a testament to the British leaders and soldiers’ resolve and professionalism that they survived at all

The Redcoats fighting at the Bloody Angle faced several disadvantages. Perhaps foremost, the Patriots outnumbered them more than 2-to-1. The British decision to supply each man the basic load of 36 rounds of shot and not plan for resupply also began to tell as they ran short of ammunition. If Smith allowed the column to stop and engage the militia, his force would be overwhelmed by the Patriots. There wasn’t even time for the British to tend to casualties, so they left wounded comrades to their fate along the road. Most officers were dead or wounded, so the redoubtable British sergeants took over and kept the column moving forward. Their situation was becoming critical. At that point, midway between the two bends, the British began to break.

The Redcoats double-timed it uphill toward the second bend, where militiamen from Concord and other towns were waiting for them. As the British approached the bend on the run, the Patriots unleashed a volley. The Woburn Militia also continued firing on them from the woodlot across the road. Although staggered by these vicious attacks, the column kept moving. Then the Redcoats caught a break.

The terrain, which had plagued the British all day, suddenly became their ally. One hundred yards past the second bend Bay Road crested a hill and began a gentle descent for a half mile. To the weary Redcoats, running downhill must have seemed a godsend. Also in their favor was the roadside terrain, which past the second bend became overgrown and swampy, slowing Patriot pursuit. Although exhausting for the British, running had saved their lives. Though far from out of danger, they had survived the Bloody Angle and had a few minutes to regroup until the Patriots reorganized and resumed their attacks.

The Redcoats had entered Bloody Angle as an organized military formation and emerged a bloodied mob. It is a testament to the British leaders and soldiers’ resolve and professionalism that they survived at all. Had they been less resolute, the whole column could have been annihilated or captured. Eight Redcoats died outright during the fighting at Bloody Angle, 30 more received wounds of varying severity and an unknown number went missing or were captured. The figures represent nearly 15 percent of all British casualties during the retreat from Concord to Boston. The day after the battle locals buried five of the Redcoats killed at Bloody Angle in a little cemetery in Lincoln. Other British dead still lie where they fell along Bay Road.

The Patriots did not escape unscathed. Several Massachusetts militiamen were wounded at the Bloody Angle, and three were killed—Jonathan Wilson of Bedford, Nathaniel Wyman of Billerica and Daniel Thompson of Woburn. Redcoat flankers inflicted most of the Patriot casualties. Compared to the losses of their adversaries, however, militia casualties were surprisingly light.

The British survivors of the Bloody Angle weren’t out of the woods, as the Patriot militias quickly regrouped and resumed their attacks on the beleaguered column. Had Smith’s command not received reinforcements at Lexington in the form of 1,000 men and two cannons under the command of Brig. Gen. Hugh Percy, they would never have made it back to Boston. As it was, militiamen from all over eastern Massachusetts gathered along the British escape route and turned their retreat into one long, bloody running fight. The British eventually reached Boston, but not before feeling the full wrath of the Massachusetts militia at the Bloody Angle. MH

Historian and retired Army officer Douglas L. Gifford specializes in American military history. For further reading he recommends American Spring: Lexington Concord and the Road to Revolution, by Walter R. Borneman; Paul Revere’s Ride, by David Hackett Fischer; and Lexington and Concord: The Battle Heard Round the World, by George C. Daughan.

This article appeared in the September 2021 issue of Military History. For more stories subscribe here and visit us on Facebook.