Samuel Fuller reinvented the American war movie with such gritty classics as The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, and The Big Red One.

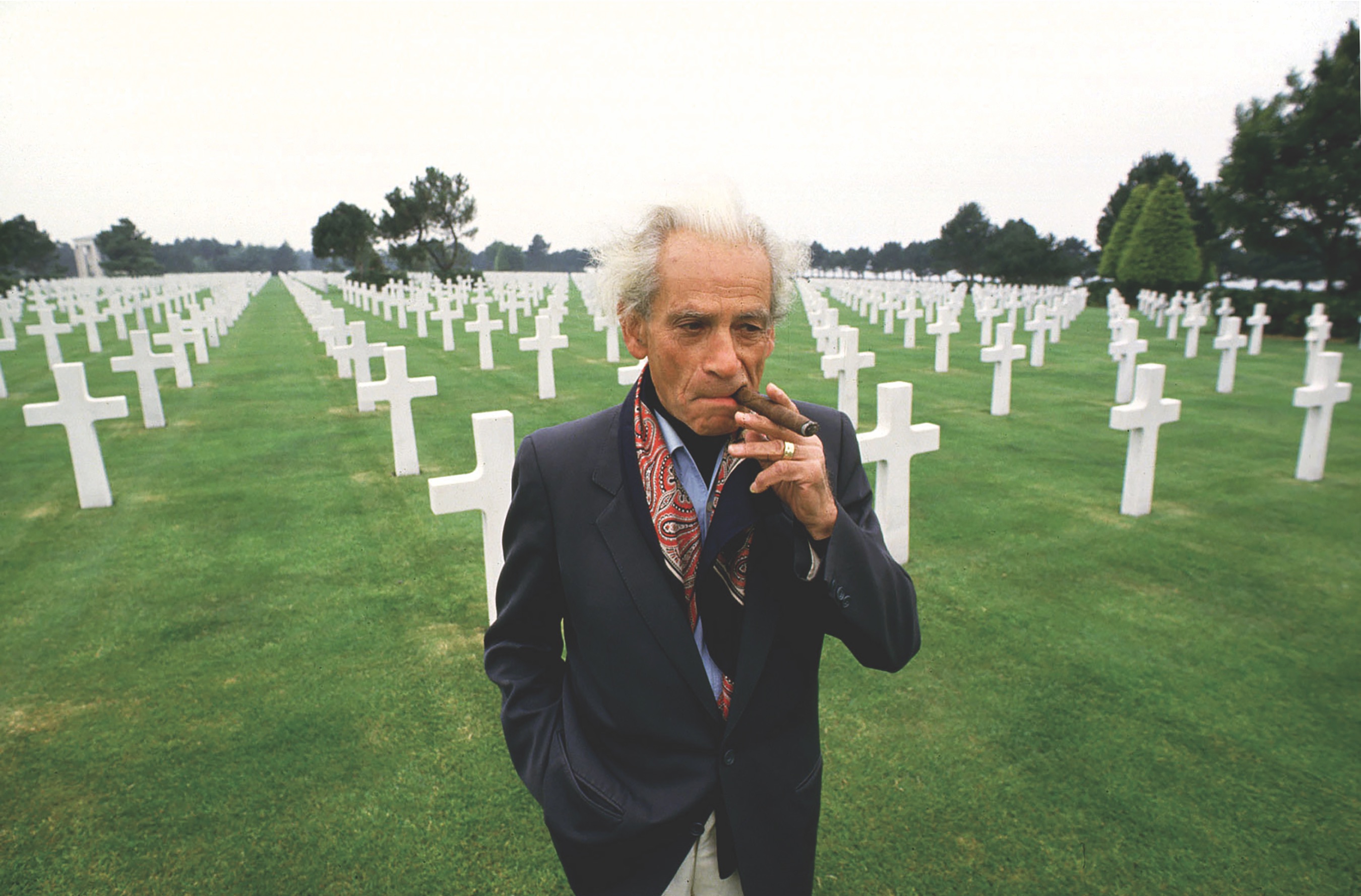

Listen up, dogface: Samuel Fuller taught the movies how to talk about war like a real soldier. As an infantryman in the legendary “Fighting First” infantry division during World War II, Fuller fought from Africa to Sicily, landed in the third wave at Normandy, and moved with his division through Europe before helping to liberate the Nazi concentration camp at Falkenau. When he returned home after the war and launched his career as a screenwriter and director, Fuller was determined to depict and honor his fellow soldiers and their epochal experiences in battle. He did just that in a career that spanned more than 50 years, leaving a legacy of straight-shooting, honest films that remain remarkably fresh and influential.

Fuller was driving in Los Angeles on December 7, 1941, when he heard reports of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He went immediately to the draft office, and soon, at age 29, he was an infantryman in the U.S. Army. He’d already worked half a dozen different jobs on both coasts and in between. Born in New York City to Russian and Polish immigrants, he’d become the personal copyboy for legendary newspaper editor Arthur Brisbane and then perhaps the world’s youngest crime reporter, when at age 17 he began chasing ambulances for the notorious New York tabloid Evening Graphic. He quickly learned the value of a dramatic story, a screaming headline, and a sense of the ridiculous. Writing brought him to Hollywood, where he began producing low-budget stories for Columbia Pictures in the 1930s. When the war came, Fuller was ready. “I had a helluva opportunity to cover the biggest crime story of the century,” Fuller would recall in his autobiography, “and nothing was going to stop me from being an eyewitness.”

After basic training, Fuller and his comrades made their first landing at Arzew Beach, Algeria, on November 2, 1942, where they met Vichy French in a brief but deadly skirmish and where Fuller saw his first fellow soldier killed. In February 1943, as his unit proceeded through North Africa toward Tunisia, it was intercepted and decimated by German field marshal Erwin Rommel’s more experienced Africa Korps at Kasserine Pass. “We were like babes in the woods, trapped in the crossfire,” Fuller would recall. “There was nothing to do but die or retreat.” But his outfit rallied, and with the help of the Twelfth Air Force retook Kasserine Pass as Operation Torch, under the command of Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower, secured an Axis surrender in North Africa on May 9, 1943. Fuller’s first major mission was complete, and he was still alive to report what followed.

Colonel George A. Taylor, the commander of the 16th Infantry Regiment, assigned Fuller to document the unit’s activities, battle by battle. In July the 1st Division headed for Italy. Operation Husky—the Allied plan to wrest Sicily from the Germans—was underway, and the next chapter of Fuller’s war journal would be written more in blood than ink, with ferocious fighting at Gela, on Sicily’s southern coast, and a week of violent battles against Axis forces in the hills and mountains surrounding Troina, in central Sicily. Victory at Troina finally gave Fuller and his fellow soldiers time to rest and regroup for their next mission: Operation Overlord, the Allies’ top-secret plan to invade Nazi-held Western Europe. Fuller’s landing spot bore only the code word Omaha—“three syllables,” he later wrote, “that would be part of my very being for the rest of my life.”

Assigned to land on Omaha Beach in the third wave of the Normandy invasion, Fuller was utterly unprepared for what he would experience there: the bloodshed and chaos he saw was beyond description—beyond belief—and despite his frontline experiences at Arzew and Gela, Fuller was overtaken by the insanity of battle:

Machine guns rattled from up above, dropping dogfaces in the surf, turning the ocean red. Human screams were drowned out by the shrieking artillery shells that fell out of the foggy sky. Mines exploded underfoot. Smoldering bodies were everywhere. As thousands of dogfaces debarked, hundreds and hundreds dropped into the surf and across the sand. Heads, arms, fingers, testicles, and legs were scattered everywhere as we ran up the beach, trying to dodge the corpses. I saw a man’s mouth—just a mouth, for Chrissakes!—floating in the water.

Despite the horrific carnage, Fuller and his comrades kept moving, with Taylor leading the way. “There are two kinds of men out here!” Taylor had shouted. “The dead! And those who are about to die! So let’s get the hell off this beach and at least die inland!” Fuller had survived the death trap of Omaha Beach, but the unimaginable still lay ahead.

From September 1944 until April 1945, Fuller and his battalion drove the German army through France into Aachen and then finally to Czechoslovakia. After the ceasefire was declared on May 7, Fuller’s unit arrived at Falkenau, where on the outskirts of town they discovered a camp that bore the sign Konzentrationslager. The masses of dead, all innocents, overwhelmed the soldiers with a unimaginable hell. “In one building, we plopped down behind a white mound to take cover from any last Nazi defenders,” Fuller would recall. “It was only then that I realized that the mound was a heap of human teeth wrenched from the camp’s victims.”

Fuller, who had received a movie camera from his mother during the war, was asked to make a short film about the Falkenau camp that he would later describe as “my first movie.” With the camera his mother had sent him, Fuller filmed the liberation of the camp’s survivors alongside the unspeakable remains of the dead. He never again looked at the footage.

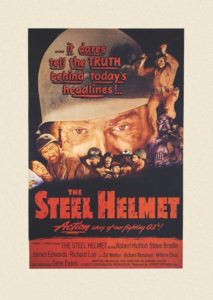

Fuller returned home in September 1945 and began in earnest the filmmaking career that would define the rest of his life. He made a pair of low-budget westerns for independent producer Robert Lippert, and their modest critical and financial success gave Fuller his longed-for opportunity to make a war picture. The Steel Helmet, filmed in only eight days at Los Angeles’s famed Griffith Park, was released to controversy and celebration in early 1951. The story of a small unit of Korean War grunts who take shelter in a Buddhist temple, its look and feel is wholly unlike previous Hollywood portrayals of combat. Fuller’s leading man—Gene Evans, an unknown actor and Engineering Corps veteran—was the opposite of a John Wayne or Gary Cooper. With a stocky, brawny build, a set of uneven teeth that covered his mouth like logs atop a manhole, and a doughy face half-covered in stubble, Evans, as Sergeant Zack, dominates the action without glamour or false theatrics. True to Fuller’s firsthand experience in combat, Zack is too busy surviving to worry about glory.

Unlike the fresh-faced and wholesome poster boys of other war movies, Zack and his fellow infantrymen are tired, filthy, confused, and more concerned with finding food and shelter than with fighting. Fuller’s company is diverse, compelling, and thoughtfully shaded: There’s Corporal Thompson, the African American medic; Private Bronte, the conscientious objector who carries a small organ instead of a gun; and Sergeant Tanaka, the Nisei, each an outcast back home by race or class. Yet here, in the Buddhist temple, the men are equals.

Fuller’s coup in The Steel Helmet is to introduce a Korean enemy soldier, hiding in the temple, who, after being taken prisoner, begins to psychologically subvert his captors. The blunt questions he asks them are shockingly provocative for movie dialogue in 1951: Is it true that black soldiers can’t sit to eat with whites in the United States? That their bus tickets cost the same money but only seat them in the back? That Japanese Americans were placed in internment camps during the war? The three soldiers do their best to counter his verbal attacks with humor and indifference, but the reality of inequality back home makes their effort a problematic one.

Sergeant Zack is no hero, but he is a fighter and the closest thing his unit has to a leader. The men have no reassurance from high command, no refuge but the temple, no working radio. The Steel Helmet is a chamber drama. The soldiers here are fighting for another day, not a medal.

The film’s controversial depiction of the shooting of an unarmed prisoner and a raft of critical reviews condemning it as procommunist, antisoldier, and subversive piqued Americans’ curiosity, and people flocked to see it. It was Fuller’s first big hit as a filmmaker, and it gave him the chance to continue telling his stories. Hollywood, always eager to repeat a success, came knocking.

Darryl F. Zanuck, the controlling executive of 20th Century Fox, signed Fuller to a multifilm contract and gave him his first assignment: to make a bigger, better version of Steel Helmet. That film, Fixed Bayonets, is stunningly bleak, claustrophobic, and frightening. The setting is again Korea, and Evans returns in the starring role. The men suffer frostbite, dodge a bullet ricocheting on cave walls, and labor under the strong possibility that theirs is a suicide mission, with little glory in store.

In one of the finest sequences of any war film, Fuller illustrates the soldiers’ suicidal risk with high suspense. Actor Richard Basehart, playing the nervous, unseasoned

third in command, is determined to save his last remaining superior, who lies wounded at night in the middle of a field the soldiers had earlier rigged with landmines. The problem—and what a problem—is that the wounded lieutenant has the map locating the mines. Basehart and the others watch helplessly as their medic is killed trying to reach the lieutenant. Basehart ultimately has to retrieve him, and for three breathless minutes, we watch as he takes each tentative, potentially deadly step. The only sound is the snow softly packing beneath his boots. Fuller knew, in only his second war film, exactly how to illustrate the awful reality of luck in a soldier’s survival. Sometimes you just step right.

The rest of Fixed Bayonets builds from this sequence and frequently mirrors the story and characters in The Steel Helmet. Both films bear the eyewitness truth of a real infantryman’s war memories, and in both, the smallest details ring truest: that dry socks are more important than battle strategy, that frostbite is as deadly as a landmine, and that mere survival is a soldier’s only ideology. When the film ends, flares light the sky to show the survivors the way to rejoin their division. The grim faces of the lucky living do not draw a triumphant curtain on the film; they simply stare ahead.

Fixed Bayonets was another success for Fuller, and his contract with Zanuck led him through a series of increasingly big-budget, unusual movies. With House of Bamboo, a 1955 thriller set in Japan, Fuller became the first filmmaker to shoot on location in postwar Tokyo. Verboten! (1959) is a love story set amid the ruins of occupied Germany, where an American soldier’s affair with a local woman suggests the eventual reconciliation of the two nations. As his career continued to grow, there was no story Fuller wanted to tell more than The Big Red One. Alas, his quest to film and release this dream project would prove the most difficult and demoralizing of his career.

By 1961 Fuller was at an impasse. His contracts with Zanuck at Fox and Harry Cohn at Columbia Pictures had both ended, and when he approached Warner Brothers executives with the idea of turning his war journal into a picture, they were enthusiastic—if he first agreed to make Merrill’s Marauders, the story of Brigadier General Frank Merrill’s “Galahad Unit,” which became famous for its deep-penetration missions behind Japanese lines in Burma. Fuller reluctantly agreed, only to be rewarded with a cursed production and a finished film whose central sequence had been reshot by another director. Fuller had been right to treat the project warily, and his suspicions were all proved true by both the troubled production and the release of what Fuller felt was an artistically compromised product. He needed to tell his story, and he needed to do it his own way.

After 15 years making independent, muckraking contemporary dramas and occasional for-hire work, Fuller’s script for The Big Red One ballooned to 1,000 pages. He had too many memories, too many stories, and every one of them felt equally important. In 1978 Fuller finally had a green light. After assembling a cast headed by Lee Marvin, who had fought as a marine in the South Pacific, he led his men into battle. With limited resources and a tight shooting schedule, they would have to recreate Algeria, Sicily, Normandy, and Falkenau on location in Israel.

The Big Red One was finally released in July 1980 to good reviews, but it was largely ignored. Audiences had turned their attention to movies about Vietnam, and on the heels of the Academy Award–winning The Deer Hunter in 1978 and the iconic Apocalypse Now in 1979, The Big Red One looked like a fossil. That’s because it was, just as Fuller had intended. Fuller didn’t need advanced technology or a more generous budget to put his story on the screen. He just needed a few well-chosen actors, some gunpowder and explosives, and the truth. The film, as released, had all of these. But the studio, handed a three-hour episodic opus, had balked at the length and cut some of the most memorable and outrageous—the most Sam Fuller—moments. Fuller had to accept the possibility that his movie would never be seen as intended. He died in 1997, at age 86, several years after suffering a stroke.

In 2004, under the supervision of the late film historian Richard Schickel, The Big Red One was reconstructed, and much of the missing footage properly reinstated. The film, now close to three hours long, was free to breathe, to boast, to gasp, and to let audiences see Fuller’s real-life war. There is George Taylor on the beach at Normandy, bellowing at his men to follow him; Fuller’s unit delivering a baby inside a tank; the skirmish with a squad of German soldiers in a mental institution, the patients indifferent to the carnage around them; even a cameo by Fuller himself. Here, appropriately, Fuller is in uniform, camera in hand, filming reality. Finally, at the end of The Big Red One, Fuller pays homage to The Steel Helmet by having Marvin, who’s just stabbed his Nazi doppelgänger, see the headline in the newspaper the dying man is holding and realize that this last act of violence had been unnecessary. The war was over. “You’re going to live,” Marvin growls at the German, “if I have to blow your brains out.”

The Big Red One is an enduring monument to Samuel Fuller, the writer, soldier, raconteur, and prodigal filmmaker who virtually invented the now familiar form of the war-film-as-memoir. Borrowed later by such movies as Platoon and Jarhead, The Big Red One retains Fuller’s humor and outrage, his ultimate belief in the grandeur of the little man who challenges the world to a fight—and lives to tell about it.

Philip Burton Morris is a writer and film historian. He lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Artists | The Auteur

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!