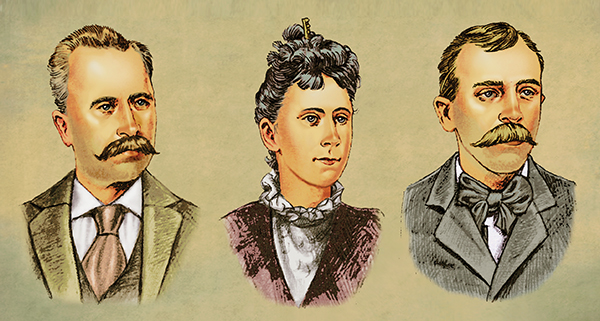

Susie E. Belew kept house for brother Louis at his modest home in Dixon, California, in the 1890s. Louis owned and managed the Arcade livery and feed stable, three blocks from the house, and his one employee, Bruno Klein, boarded with the Belews. The two men rose early each morning and walked to the stable to ready things for that day’s work. Then, per their custom, Louis would return home to eat breakfast with his sister. When Louis arrived back at the stable, Bruno would walk home to be served breakfast by Susie. The employee/border would then rejoin Louis at work.

On Monday, Nov. 8, 1897, Louis and Susie shared a breakfast of eggs, mush and coffee, and then Louis returned to the stable, freeing Klein to have his breakfast. When Klein got to the house, he found Susie too ill to serve him, so he served himself coffee and a small portion of mush and eggs. Susie grew sicker, with severe stomach cramps, purging and vomiting. Klein hurried back to the stable to report Susie’s illness to her brother, only to find Louis had also taken ill with similar symptoms. Klein summoned Dr. William A. Trafton, but soon after he too began to feel ill. In short order the doctor determined all three must have eaten something that had spoiled. He examined their vomit and found sauerkraut, which the trio had consumed the previous day. His initial diagnosis: They were suffering from acute indigestion.

The doctor ordered rest and hot drinks to ease the stomach pain. The ill men rested in the stable, while neighbors Mrs. Eugene Ferguson and Mrs. George Ehmann cared for Susie in the Belew home. (Louis was engaged to the Fergusons’ daughter Clara, while Susie was engaged to George Ehmann’s brother Charles.) Frank Belew, a brother to Susie and Louis, soon arrived at the house and sat up with his sick sister, holding her hand and trying to comfort her. But her pain persisted, and in the stable their brother and Klein continued to suffer. By sundown all three were noticeably worse, and Louis died at midnight. Earlier in the day Mrs. Ferguson and Mrs. Ehmann had prepared beef broth for Susie, but she would not drink it. To encourage Susie to at least taste the broth, the neighbor ladies each swallowed a teaspoonful of it. Both promptly vomited and later suffered from symptoms similar to those of the three victims. They would recover in a day, but Susie was not as fortunate. She died at 5 o’clock on Tuesday morning, November 9. Bruno Klein’s health was touch and go for a few tense days, but he managed to rally. In time he would come to realize how fortunate he’d been to have eaten a small breakfast on the 8th.

In the latter half of the 19th century California, like the rest of the Wild West, had more than its share of badmen and deaths by shooting, with males most often in the roles of killer and victim. The episode that played out at the Belew house in Dixon was something different—two deaths by poisoning, with one of the victims a young lady.

Chemist J.K. Grinstead found that ‘the water was strongly impregnated with the death-dealing poison,’ and that a white powder residue found on the lid of the kettle was indeed arsenic

Solano County coroner F.W. Trull started his inquest on November 10, though jurors could not arrive at a conclusion until the stomach contents of the dead siblings had been analyzed. Early suspicion fell upon Harry Allen, a jilted suitor of Susie Belew’s who, the rumor mill suggested, could have been motivated to act rashly on the premise, “If I can’t have her no one will.” Could he or someone else have poisoned the Belews’ well water? A local chemist ran tests, but the well water proved uncontaminated. Next, high school chemistry teacher J.K. Grinstead tested for arsenic in the water from the Belew teakettle. Mrs. Ferguson and Mrs. Ehmann had used water from the kettle to brew the beef broth they had sampled, just as Susie had used kettle water to prepare breakfast for herself, her brother and Bruno Klein. Grinstead found that “the water was strongly impregnated with the death-dealing poison,” and that a white powder residue found on the lid of the kettle was indeed arsenic. San Francisco chemist William T. Wenzell tested the beef broth and on November 12 confirmed it, too, contained a strong dose of arsenic. Wenzell later examined Susie’s liver and found one-tenth of a percent of arsenic present. In most cases of fatal arsenical poisoning the arsenic is absorbed by the body and not still detectable in the victim’s liver, but Susie’s dose had been so large it could not be fully absorbed. This evidence confirmed the suspicions of many—Susie had been murdered, and brother Louis as well. Thomas Belew, another brother, then posted a reward of $250 for the arrest of the murderer.

By November 13 Bruno Klein was up and about, though he lapsed into a spasm and collapsed during a visit to the doctor that afternoon. It proved a temporary setback. Klein improved rapidly and would fully recover from his ordeal. Meanwhile, Frank Belew joined Harry Allen on the list of suspects, despite having sat up with his dying sister on November 8. Frank quickly provided an alibi.

As he told it, on Sunday, Nov. 7, he had come from his ranch to Louis’ house, arriving at 4:30 p.m. and an hour later sitting down to dinner with brothers Louis and Thomas, sister Susie and a woman named Lou Bremley. Frank claimed that at 6:30 p.m., when Susie’s fiancé, Charles Ehmann, arrived, he left for town. Susie and Charles were left alone together. According to Charles, at 9:30 p.m. he went to the well for a drink of water, and before returning to the parlor, he locked the exterior doors to the house, so no one could have entered unnoticed after 9:30 p.m. Charles stayed at the house until 11 p.m. Frank said that by 8:30 p.m. he had returned to his ranch, some 8 miles from Dixon. But others claimed they had seen him in Dixon at a later hour.

On November 14 officers set up a meeting with the two suspects in a room in the Brinckerhoff and Ehmann building in Dixon, and each accused the other of the murders. Harry Allen insisted he and Susie Belew were never more than friends and remained on good terms, even though Frank had insisted that Harry not visit her anymore.

“I hope that the guilty man hangs,” Harry told the gathering.

“So do I,” Frank said.

“No, you don’t,” Harry replied. “You want to hang an innocent man.”

For the sake of the officers, Harry asked Frank, “Did you ever hear Susie say one word against me?” Frank admitted he had not. Harry then leveled his accusation: “You murdered your own brother and sister for their money.” Frank denied the charge and shot back with his own accusation: “It was you who killed them because you were jilted.” Allen claimed he was in a certain saloon between 7 and 11:30 p.m. on November 7, and his alibi proved out. Still, the three surviving Belew brothers—Frank, Thomas and Arthur—all insisted that Allen had made threats, and that both Susie and brother Louis had feared him.

The meeting with Allen and Belew apparently did not settle much, as two days later San Francisco–based detective John Curtin took over the investigation, summoned all witnesses to the Arcade Hotel and interrogated each one. During his interview Frank told Curtin he had left Dixon for his ranch at 7:30 p.m. on Sunday, November 7 (an hour earlier than his prior claim), while a night watchman saw him in town an hour later, and others placed him there as late as 9:30 p.m. In any case Frank likely did not return to his brother Louis’ house after leaving there at 6:30 and certainly did not do so after Charles Ehmann locked the door at 9:30. But that didn’t let Frank off the hook. He or someone else could have dropped poison in the teakettle before 6:30. Detective Curtin determined the poisoner must have been a person familiar with the house and with the routines of Susie and Louis Belew, because their “savage little watchdog” (as a San Francisco Call reporter termed it), which typically barked at strangers, had been silent that night. Frank said he had taken ill at supper on November 7 and entered the kitchen to take a headache powder his sister had given him. But when investigators checked with Kirby’s drugstore, they learned the Belews had purchased neither headache powders nor any prescription for headaches. At the same time they found no evidence any Belew had purchased arsenic. On November 17, the morning after the meeting at the Arcade Hotel, Frank went to Woodland and hired attorney Reese Clark, explaining to reporters, “I am being hounded by detectives and followed by officers, who are trying to trap me.”

About that time Grinstead examined a pot of boiled potatoes from Louis Belew’s house and determined they, too, contained a large quantity of arsenic. Susie had cooked up these potatoes for the breakfast mush on November 8. As evidence continued to mount, Frank Belew remained on his ranch and did not go into town, likely on the instructions of his attorney. The inquest resumed on Monday, November 22. After hearing two days of testimony, the jurors retired for an hour before reaching their conclusion: Louis and Susie Belew had been killed by arsenic administered by a person or persons unknown.

Some months earlier Frank’s wife had left her husband, but she would not discuss her reasons. Nothing significant turned up in the investigation until late January 1898 when Sacramento photographer John W. Bird, Frank Belew’s brother-in-law (married to one of Frank’s sisters-in-law), stepped forward and informed authorities that on November 7 Frank had made a shocking admission to him: “I’ve just been down to see Susie. She showed me her wedding clothes and said she and Charley Ehmann are going to Nevada on a tour. They have not treated me right in regard to the estate, but I’ll have some of it yet. They’ll not live to enjoy it. Bird, I’m going to commit a terrible crime tomorrow. I’m going to commit a tragedy that will shock the whole community.” Frank had been convinced since his father’s death that his siblings had cheated him out of his fair share of the estate, and he had vowed to take revenge. Bird told investigators he had tried to dissuade Frank. “Do not do anything foolish, old man,” he said. “Think of the consequences of such a crime.” Bird had kept Frank’s admission a secret for nearly two months, hoping the courts would exonerate his brother-in-law and spare the family the embarrassment of having a relative named a murderer. But finally he became convinced Frank had had at least some part in the poisoning.

On Friday, January 28, Constable Frank Newby went to Sacramento and convinced Bird to come to his photo gallery in Dixon and arrange a meeting with Frank Belew. That Sunday morning Bird arrived in town at 9 o’clock and opened his gallery. Newby was in hiding within hearing distance when Frank arrived just before noon. After some idle conversation Bird said, “Well, Frank, you fooled them all in grand shape in this poisoning case, not to get caught,” and Frank replied, “Yes.” Bird then tried to pry an overt confession. “Frank, that was a terrible thing,” he began, “but you would not have poisoned Louis and Susie if they had treated you right with the estate before, would you?” Frank only replied, “No.” Bird persisted. “They were after you pretty hot for a while. You must have been pretty slick in getting the poison so they could not find out where you got it, for they hunted every drugstore in Sacramento and all around.” Frank agreed but would not divulge where he got the poison. After some further discussion, and assurances Bird’s wife knew nothing of the matter, Bird said, “It’s enough for you and I to know you poisoned them.” Frank again answered with a simple, “Yes,” but then changed the subject to a planned trip to Alaska. When Constable Newby reported what he’d heard to Sheriff Benjamin F. Rush, the authorities sought an arrest warrant.

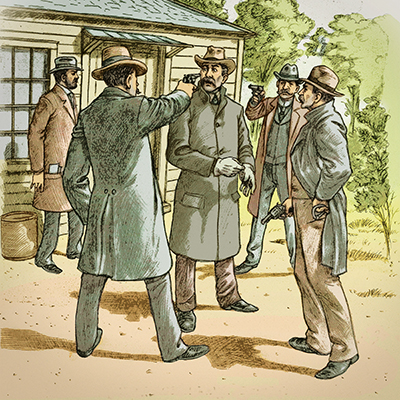

On Thursday evening, February 3, Sheriff Rush, Undersheriff T.L. Robinson, a deputy named Fitzpatrick and correspondent John F. Conners of the San Francisco Examiner traveled in two carriages the 8 miles from Dixon to Frank Belew’s ranch. It was after 10 p.m. when the sheriff knocked on the door and called for Frank to open up. “Who is there?” Frank replied from his bedroom. At that point Robinson and Fitzpatrick entered the house, while the sheriff and newspaperman covered the other exits. Fitzpatrick ordered Frank to put on his clothes and at gunpoint told him, “You are the man who killed your sister.” Frank denied his guilt and offered no resistance when the lawmen handcuffed him and brought him in a buggy into Dixon.

In the following days dark details of Frank Belew’s past came to light. A man named Charles Hough, who had done some work for Frank in 1893, claimed his boss had made two attempts on his life on the same day, most likely because Belew owed him $47 in wages. First, Frank shot off the brim of Hough’s hat, claiming the shotgun he was holding had gone off by accident. That very night, according to Hough, Frank served biscuits for dinner, but his first bite of biscuit was so bitter, Hough spit it out. On the sly he pocketed the remainder and had it tested the next day for poison. The test proved positive, Hough claimed, but authorities wouldn’t press charges on the respected rancher. Soon after Hough quit his job and moved away. It also came out that Frank had stolen $400 from his father-in-law and had stolen and butchered a neighbor’s hog. It was this pattern of criminal behavior that had prompted Frank’s wife to leave him.

Late on Feb. 5, 1898, Frank Belew admitted to newspaperman Conners he had poisoned sister Susie and brother Louis. At the district attorney’s office the next morning, he made a full confession. “This is the whole story of my crimes,” he began. “It’s too late now, for it is all over, and I must stand the consequences.” Frank claimed that his motive for murder had nothing to do with his father’s estate. He said that while Susie had always been good to him, she and Louis had spoken “evil words” against his wife, whom he loved dearly. Authorities told Frank from the outset he was under no obligation to tell them anything. “I understand the situation,” he replied, “and I know I am free, so I will make a voluntary confession that I am guilty and that I want to confess. I slept better last night after talking with the reporters.” And then he provided a flood of details:

I poisoned them with Rough on Rats [a chemical used to kill rodents], which I had had for six years or so. I put the poison in a paper, a piece of newspaper, before I left home. I came into town to the house where Susie and Louis lived after Tommy and Miss Brimley [sic] came in. Tommy and his sweetheart, Miss Brimley, had left the supper table. There was some delay at the carriage while they were all saying goodbye. I then went through the kitchen and dropped the poison through the top [of the teakettle], after lifting the lid. After I was sure that the poison was in the water, I walked into the room where Susie was preparing to meet Charley Ehmann, who was soon to marry her. She was fixing her hair at the time, and we chatted as if nothing had happened.

Frank’s wife and brothers Tom and Arthur visited him in jail. “Frank, is that confession all right?” Arthur asked him, still not convinced it could all be true. “Yes, I poisoned them both,” Frank coolly replied. Breaking down, Arthur cried out in anguish. “Why did you do it? Oh, why did you do it? You must have been out of your head.” If Frank made any reply, it went unrecorded.

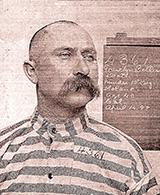

At his February 24 arraignment Frank pleaded not guilty, but five days later he changed his plea to guilty, perhaps realizing his insanity defense would not work. On April 13, after several delays, Frank was sentenced to hang at Folsom State Prison on June 16. He later fingered Bird as an accomplice in the double murder, but it was clearly a false assertion and dismissed as such.

Frank Belew, prisoner No. 4361, was delivered to a death row cell at Folsom on June 14, and the next day he made out his will, leaving everything to his children and naming his wife administrator. Over the objections of their brother Thomas, Arthur Belew agreed to arrange Frank’s burial in the family plot at Sacramento’s Helvetia Cemetery. On the morning of the 16th, Frank professed religion to a Methodist minister, but while standing on the gallows’ trapdoor, he made no statement. At 10 a.m. sharp the trapdoor was sprung, and 11½ minutes later doctors in attendance pronounced him dead. The body was then cut down, placed in a cheap prison coffin and taken to the train station for transport to Sacramento. WW

R. Michael Wilson, a retired sergeant from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, has written more than a dozen books, including a Crime and Punishment series for Arizona, Nevada and Wyoming and a Legal Executions series for 17 Western jurisdictions (except California) through Dec. 31, 2010. For this article he relied mostly on San Francisco newspapers of the time. Originally published in the August 2015 issue of Wild West.