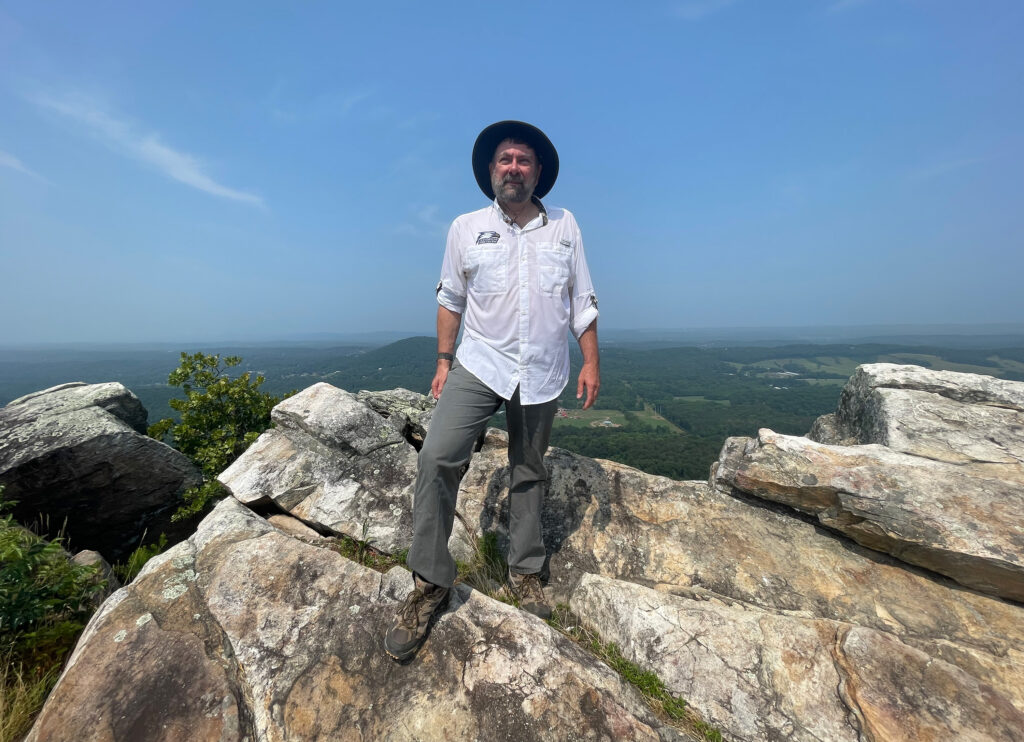

As we ascend beastly Rocky Face Ridge on a sultry afternoon, my battlefield guide Bob Jenkins—a 59-year-old lawyer, humorist, and Mississippi-born descendant of Confederate soldiers—stops and ponders which trail to take next.

Straight ahead we see what Jenkins calls the “idiot trail.” It’s especially steep and covered with loose rock, but it’s a more direct route to the crest of a ridge covered with hickory, oak, poplar, pine and silver and red maple. To our right is an easier but longer trail to the summit.

“Do you want to take the ‘idiot trail’?” Jenkins asks.

Not blessed with a particularly high IQ, I figure this one is a no-brainer. Yes, the “idiot trail” it is.

And so we trek onward on our excellent adventure, two sweaty Civil War enthusiasts eager to examine stone works and earthworks that snake throughout this ridge in northwestern Georgia. “America’s best-kept secret,” Jenkins says of the Rocky Face Ridge battlefield, “the crown jewel of the Atlanta Campaign.” Here, in the Crow Valley near Dalton, soldiers clashed from May 8-12, 1864, in an opening act of the campaign between Union Maj. Gen. William Sherman and Confederate General Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee.

Now, I’ve visited Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Harpers Ferry, and other battlefields with earthworks. But my gawd, I’ve never seen any as impressive—and as numerous—as those at Rocky Face Ridge.

Thirty yards or so off a trail, Jenkins pointed to mounds of earth piled high—the remains of an Arkansas battery position, he believes—and a deep and lengthy trench for Confederate infantry. The artillery earthworks look as if you could still roll cannons behind them, as the Rebels did in spring 1864.

“In Dalton and Whitfield County there are more undisturbed Civil War earthworks than anywhere else in the country, and that’s not just Bobby Jenkins saying that,” my guide says. “That’s coming from the people in the green hats”—National Park Service rangers.

These remarkable Civil War defenses have survived through a series of fortuitous circumstances, Jenkins says. For one, Whitfield Country isn’t densely populated, and over the years good stewards of the land have recognized the importance of the earthworks and stone works. The chief reason, however, may be that they are so hard to get to and thus have eluded destruction by humans.

This isn’t my first encounter with 1,435-foot Rocky Face Ridge. Weeks earlier, following a bike ride at nearby Chickamauga battlefield, I drove to Rocky Face Ridge Park, a few miles from dreaded Interstate 75 and a world away from Atlanta far to the south.

Short on time, I walked a trail a thousand or so yards into the woods but turned back and returned home. To fully absorb this unheralded battlefield, you need at least five or six hours and a great guide like Jenkins—the author of two published Atlanta Campaign books.

Opened unofficially in spring 2021, the 1,000-acre park is a result of remarkable work by preservation groups, including Save the Dalton Battlefields, as well as county commissioner Mike Babb. Once farmland, the park is now popular with hikers and history and nature lovers. With avid mountain bikers, too.

A sign in the parking lot warns them about the “extremely dangerous” double orange diamond trail. Months ago, a friend of mine left his broken mountain bike on the far side of the ridge and blazed a trail back to civilization. If luck is on my side, maybe I’ll find the bike’s rusty carcass.

“Are we having fun yet?” While Jenkins and I trudge along a stony, serpentine trail, he wonders about my welfare. My calves and knees ache. So do my toes in a cheap pair of hiking boots. My Fitbit registers 130 heartbeats a minute. But what an epic experience this is. Jenkins brought an 80-year-old battlefield tramper with a heart condition up here once. Lord, how did that man endure? This is a haul.

Jenkins and I limbo dance underneath a fallen tree blocking our path. Then, as we continue our march to the crest, he invites me to take the lead.

“I want you to see what’s next,” he says.

An untimely haze prevents a perfect view to the south, but it’s special, nonetheless.

“On a clear day you can see 65 miles,” Jenkins insists, “all the way to Kennesaw Mountain.” That’s where 4,000 soldiers—3,000 Union, 1,000 Confederate—became casualties in an especially bloody Atlanta Campaign battle on June 27, 1864.

To our right, Jenkins points to the craggy face of Rocky Face Ridge, jutting out like the jaw of a prizefighter among greenery. In a field far below, 14 soldiers from the 58th and 60th North Carolina (CSA) paid the ultimate price for desertion on May 4, 1864.

I wonder how much more trudging we have before we reach the far side of the ridge. “Not much farther,” he says.

Then, Jenkins, an asthmatic, pauses briefly to catch his breath.

“But don’t trust me,” he says. “I’m a lawyer.”

Finally, we arrive at Buzzard’s Roost. The steady roar of traffic on I-75 way below can’t spoil this moment. True to the name of the place, a solitary buzzard circles in the near distance. On a clear day from our lofty perch, we could see all the way to Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga—roughly 28 miles away as a buzzard flies.

“From up here,” Jenkins says, admiring the view, “we can see how the Atlanta Campaign unfolded.”

In the near distance stands Blue Mountain, where Sherman eyeballed Confederate defenses on Rocky Face Ridge before returning to his headquarters near Tunnel Hill. That’s off to our right, in the far distance. To our left, beyond a #! @*&% cell phone tower, is Dug Gap, where the armies clashed on May 8, 1864.

“This is where the ball opened,” Jenkins says of the Atlanta Campaign.

After a brief rest at the former site of a Confederate signal station, we reach the narrow spine atop Rocky Face Ridge. Alas, I have no time or energy to find whatever remains of my friend’s bike—if it’s still there.

Up here, where 2023 seems a distant memory, I marvel at stone works built by the Confederate Army. Some look as if the soldiers created them days ago. Stretches of the defenses are covered by summer growth and would be more visible in the fall.

“Aren’t 10 people in a month who see this,” Jenkins says as we walk along the spine, “and you’re one of them.”

A bear or two occasionally wander up here. Sometimes a fox, deer, and bobcat, too. And after a rainfall, it can get a “little snaky,” says Jenkins—venomous copperheads, maybe a timber rattlesnake or three. But we’re the only humans in sight advancing along the spine.

Sam Watkins, the famous Confederate memoirist, served on Rocky Face Ridge with the 1st Tennessee. I try to imagine the 24-year-old private piling rocks with his comrades and preparing for battle.

“We form a line of battle on top of Rocky Face Ridge,” he wrote in Company Aytch, his memoir, “and here we are to face the enemy. Why don’t you unbottle your thunderbolts and dash us to pieces? Ha! Here it comes; the boom of cannon and the bursting of shell in our midst. Ha! Ha! Give us another blizzard. Boom! Boom! That’s all right, you ain’t hurting nothing.”

On May 9, 1864, up here where the buzzards fly, Alabama infantry and artillery mowed down soldiers from Ohio, Illinois, and Kentucky who charged four abreast along the narrow spine of the ridge.

“One of the hardest places I ever saw,” a 64th Ohio corporal said of this battlefield.

In less than 30 minutes, 40 U.S. Army soldiers were killed and 110 wounded. Benjamin McCoy, a 21-year-old corporal in the 64th Ohio, fell with a mortal wound through the lungs. He lingered for more than a week.

“Benjamin, as a soldier, was free from the many vices that constantly beset the path of young men in the army, and knew only his duty in the cause which he so early espoused, and for which he offered up his youthful life,” a lieutenant in McCoy’s regiment wrote the soldier’s parents.

We reach the site of the high water mark of the U.S. Army’s advance. It’s the most remote battlefield I have ever visited. For several yards we see palmettos, each about two feet high, sprouting from the ground. Jenkins likes to think they symbolize where the bluecoats fell.

“You are standing right now in no-man’s land,” he tells me. “This is a killing zone.”

We briefly rest on a huge boulder. Then Jenkins tells the story that for me at least speaks to the futility of war. Following the doomed charge of Brig. Gen. Charles Harker’s brigade on May 9, a wounded Union soldier cried out from the unforgiving terrain.

Alexander McIlvaine, the 45-year-old colonel of the 64th Ohio, ordered a captain to rescue the soldier in no-man’s land.

“Colonel, it will be certain death to any man who attempts to pass between those rocks,” the officer said. “If you order me to go, I will obey, but I will not send any one of my men. If you wish to put me in arrest, here is my sword.”

“I will go myself!” McIlvaine replied.

As the colonel walked along a narrow path between boulders—the path we had just followed—a bullet crashed into his bowels, mortally wounding him.

Our descent becomes a blur of more stone works—including those for Union artillery this time—and slips and slides along the trail. A mountain biker rumbles up our path, destination unknown.

More than four hours after we had begun, Jenkins and I spy our starting point in the Rocky Face Ridge Park lot. Our epic 8.5-mile hike is on the cusp of completion.

“Hallelujah,” he says.

Hallelujah, indeed.

John Banks, a longtime journalist, is the author of three Civil War books and a popular Civil War blog. His latest book is A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime (Gettysburg Publishing).