An underlying factor in the Confederacy’s eventual loss of the Civil War was President Jefferson Davis’ often-shaky ties with his generals. Nowhere was that more evident than Davis’ rocky partnership with Joseph E. Johnston. At the onset of the war, Johnston was in the middle of a tug of war between his native Virginia and the new Confederate government. When Davis began doling out promotions for some of his top officers, however, once-cordial relations turned sour for Johnston and his new commander in chief. Unfortunately, that animosity continued throughout the war. To his credit, Davis kept the proud Virginian in the command mix until the end. From the war’s first major engagement at Manassas, Va., to his surrender of the remnants of the Army of Tennessee in late April 1865, Johnston remained at the forefront of the war effort.

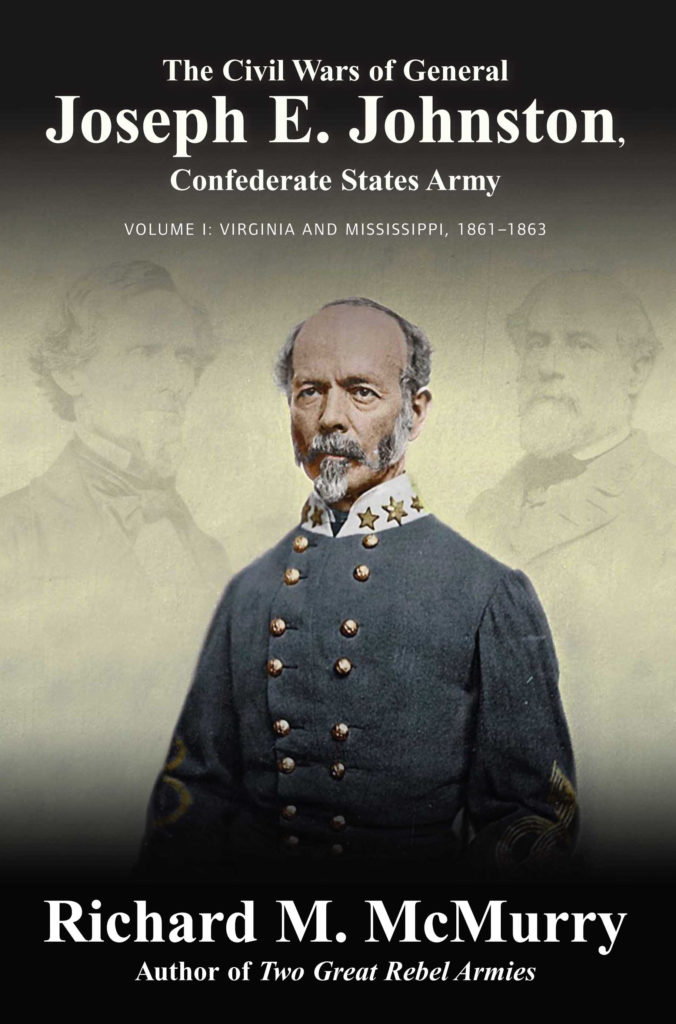

For his latest book, The Civil Wars of Joseph E. Johnston, Confederate States Army: Volume 1: Virginia and Mississippi, 1861-1863 (Savas Beatie, $34.95), esteemed historian Richard M. McMurry scoured resources in archives across the country for rare material. The result is an insightful look at one of the war’s more intriguing characters.

Joe Johnston has been the subject of a great deal of literature already. What new material were you able to find?

Well, I found some diaries and letters that had not been used before, as well as many newspapers. The most important collection of letters that I found were those of Lieutenant Richard Manning, who served on Johnston’s staff from 1861 to 1863. He had many interesting insights into Johnston’s interactions and feelings, especially toward Generals Leonidas Polk and John Pemberton. He was not a big fan of either, but especially not partial to Pemberton.

Another source I stumbled across was that of Sue Harper Mims. She was married to Livingston Mims, who was on Johnston’s staff during the war and subsequently his business partner afterward. I also had a young man at the Mississippi Department of Archives who led me to the journal of Thomas B. Mackall. He was an aide and cousin of General William W. Mackall, who served on Johnston’s staff. That journal contained many gems about Johnston.

Who had a bigger hand in having Johnston join the Confederate Army: Davis or Johnston himself?

Before the official start of the war, prior to Virginia seceding and the formation of the Confederate States of America, the state of Virginia sought out both Johnston and Robert E. Lee, natives of the commonwealth, to join their militia forces. When Governor John Letcher and later Jefferson Davis tried to sway the high-ranking officers, both were still enlisted in the United States Army. Both entities did their very best to recruit them to their cause, with Davis winning out in the end.

How quickly did the relationship between Johnston and Jefferson Davis unravel?

The animosity between Johnston and Davis began the moment Johnston joined the Confederate Army. The date was September 1861, and it began over Johnston feeling devalued at the rank Davis bestowed upon him. Many of his fellow officers were given a higher rank [he was fourth in seniority behind Samuel Cooper, Albert Sidney Johnston, and Robert E. Lee]. Johnston had already begun arguing with the Confederate government officials upon his assignment to command at Harpers Ferry, Va., back in May of 1861. At that point, many of those government officials drew Johnston’s ire, but Johnston did not yet have any friction with Davis.

What is your opinion of Johnston’s performance against Union General Robert Patterson in the buildup to the First Battle of Manassas?

I do not go into great detail of that aspect of Johnston’s career. The main focus of this first volume is Johnston’s quarrels with Davis contrasting Lee and others. Johnston was generally ambiguous toward Lee. He respected Lee, but he was also jealous of him—very resentful of the praise Lee received. It never occurred to Johnston to ask why Davis didn’t like him.

How did Johnston contribute to the victory at First Manassas?

He did his complete job at Bull Run and acquitted himself as a professional soldier, which he had been trained to do. His aides were relaying orders all over the field on his behalf.

How was Johnston’s defense of Richmond during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign?

I do not cover in-depth of what Johnston had planned to do in defense of the Confederate capital. There are many factors in examining that, including his alienation of government officials as well as President Davis. His wounding at Seven Pines on May 31 quickly caused plans to change after Robert E. Lee was inserted into Johnston’s position.

You discovered new information about Johnston’s wounding at Seven Pines. Explain.

Johnston was wounded twice at Seven Pines. He was shot both in the chest and in the shoulder, both painful and serious wounds. All of mid-1862, Johnston was unable to perform any military duties, either on the field or at a desk. When it seemed Johnston had finally recovered from his wounds in November 1862, he was injured yet again. This little-known account occurred on a train ride between Atlanta and Montgomery, Ala. His rail car ran off the tracks, rolled over and slammed against a tree. Johnston was slung across the car and landed on top both Lt. Manning and a member of Patrick Cleburne’s staff. This definitely reaggravated his healing wounds from Seven Pines. Johnston also became very sick in the spring of 1863, about when he was sent to Mississippi. That was partially due to his wounds; the rest was the result of the normal diseases rampant at that time.

What was the reasoning behind Davis’ decision to hand Johnston such a lofty command in the West in 1863?

Davis appointed Johnston to command in the Western Theater command to provide direction to both Pemberton and Braxton Bragg. Remember, Johnston disliked Pemberton, and it only grew worse when he came into close contact with the Vicksburg garrison commander. Johnston actually liked Bragg at this juncture, from 1862 to 1863. He had reason not to. Johnston’s resentfulness of Bragg came only after he replaced him as commander of the Army of Tennessee. At this point, Bragg was appointed to Davis’ administration, which was sufficient enough to draw Johnston’s scorn. Bragg also eventually came to resent Johnston taking his place in command of the Western forces. Johnston had friction, too, with William Hardee, Bragg’s interim replacement. He felt Hardee was fine as a division or corps commander, but nothing higher.

Tell us more Johnston’s time in charge of the Army of Relief in the West.

Johnston absolutely hated serving in the Western Theater. He preferred to serve in the Army of Northern Virginia again. However, Johnston kept asking Davis for a command. With Davis needing someone to monitor such a large area, he relented and sent Johnston. Upon his arrival in Mississippi, Johnston became sick again and Dr. Yandell was constantly at his side taking care of him. To top it off, when well, Johnston twice had to abandon Jackson, Miss.

How do you feel Johnston handled matters in the eventual loss of Vicksburg? Where did things stand for him as 1863 ended?

Vicksburg could not have been saved and Pemberton was wary of abandoning it. Vicksburg was so messed up, nothing could have been done to save it or its garrison. Johnston should have just specifically ordered Pemberton to leave the city entirely. Pemberton’s brief departure from Vicksburg was not in full force and he was quickly defeated at Champion Hill and removed his forces to the trenches again. Nothing could have been done to wrest the city from Federal forces by the time Johnston arrived on the scene.

As for his besieged troops in Jackson, Johnston was totally unprepared to stay there. He had no supplies for a siege and would have starved and had to surrender the city like Pemberton eventually had to do at Vicksburg.

Johnston ended 1863 at the Huff House, his headquarters at Dalton, Ga. He would go on to jump start the Army of Tennessee into an effective fighting force again as the calendar turned to 1864. Volume 1 of my book mainly covers Johnston’s feud with Davis and his administration and his time in the West.

The Civil Wars of Joseph E. Johnston, Confederate States Army

Volume 1: Virginia and Mississippi, 1861-1863

By Richard M. McMurry, Savas Beatie, 2023

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.