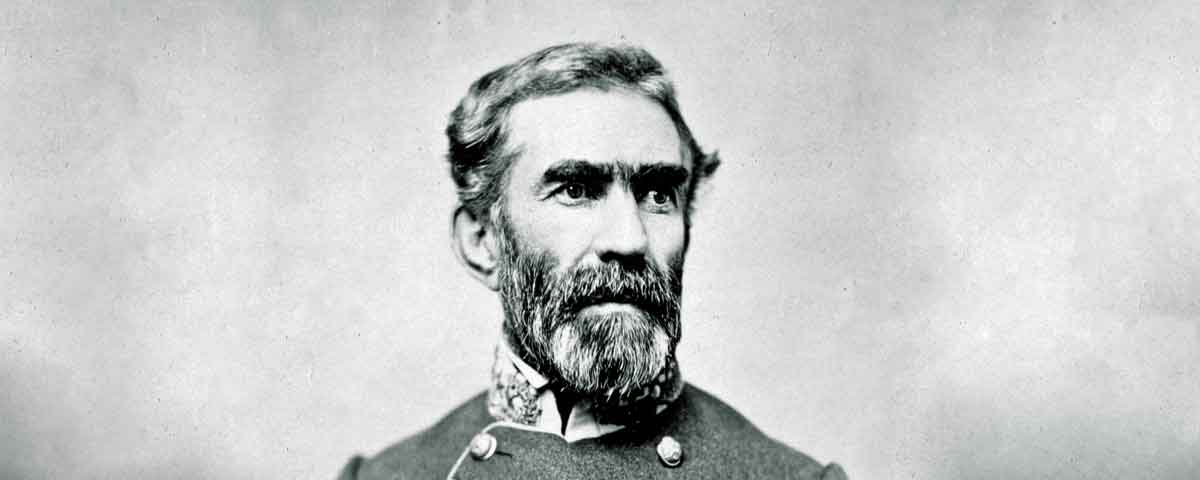

Confederate General Braxton Bragg was arguably the Civil War’s most hated commander. Long afflicted by painful rheumatism, chronic stomach ailments, and severe migraines that helped fuel his unpleasant disposition, Bragg was short-tempered, aggressively argumentative, publicly critical of superiors, quick to berate subordinates, and exercised a strict-disciplinarian command style that alienated the Civil War’s mostly volunteer soldiers. He generally was obnoxious to everyone, in fact. Even President Jefferson Davis, who gave him command of the principal field army in the war’s Western Theater, didn’t much like Bragg—and, perhaps more important, neither did Bragg’s senior subordinates. Tellingly, in the wake of the Confederates’ hard-won tactical victory at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19-20, 1863, Bragg’s major subordinates petitioned Davis to relieve their despised leader of his command. One of those subordinates—the South’s brilliant, fiery “Wizard of the Saddle,” Nathan Bedford Forrest—reportedly even threatened to kill Bragg!

Yet it is a military maxim that subordinates, whether they love or despise their commander, must do one all-important thing: promptly carry out legal orders. At Chickamauga, Bragg’s senior subordinates ignored this basic leadership precept, thereby helping turn a much-needed tactical victory into a strategic disaster for the South when two months later, nearby Chattanooga, Tenn., was transformed from a starving, besieged Union enclave into the vital launching pad for Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 1864 Atlanta Campaign and devastating March to the Sea.

Bragg’s principal subordinates—his army’s “wing,” corps, and division commanders—must share responsibility with him for arguably losing the war in the West. Among those contributing to Bragg’s strategic defeat (each of them to a greater or lesser degree) were: Lt. Gens. Leonidas Polk, Daniel Harvey Hill, and James Longstreet; as well as Maj. Gens. Simon Bolivar Buckner, Thomas C. Hindman, John Bell Hood, Alexander P. Stewart, W.H.T. Walker, and Joseph Wheeler. Although later historians tend to place full burden for strategic defeat on the easiest target, the much-despised Bragg—another military tenet, of course, is that the commander is ultimately responsible for all his unit does or fails to do—several of his subordinates’ actions reveal that blame should not be borne solely by the Confederacy’s most hated commander.

Born March 22, 1817, in Warrenton, N.C., the beetle-browed Braxton Bragg—who by 1863 sported large patches of gray in his dark hair and beard—had admirably finished fifth in his 50-member West Point Class of 1837. Classmates included Union Generals William H. French, John Sedgwick, and “Fighting Joe” Hooker, and Confederate Generals Jubal Early, John C. Pemberton, and W.H.T. Walker (as well as class dropouts Lewis A. Armistead and St. John R. Liddell).

Like many West Pointers, Bragg excelled during the 1846-48 Mexican War, winning three brevet promotions (no U.S. officer won more). Notably Bragg, 29 at the time, received well-deserved laurels as an artillery battery commander at the crucial 1847 Battle of Buena Vista. During that battle, Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor famously exhorted Bragg to repel a dangerous Mexican assault by giving the enemy “a little more grape[shot], Captain Bragg!”—more likely, Taylor ordered, “Double-shot your guns [with anti-personnel canister], and give ‘em Hell!” Nevertheless, Bragg’s cannons turned a potentially disastrous defeat into a resounding victory, making him a national hero (he would be individually honored in New York, Washington, and New Orleans).

Following the Mexican War, Captain (Brevet Lt. Col.) Bragg endured routine duty at isolated frontier garrisons until, effective January 1856, he resigned from the Army. Not quite 40, Bragg settled upon a slave-worked Louisiana sugar plantation, while also serving as a state militia colonel. After Louisiana seceded on January 26, 1861, Bragg (who opposed secession) was appointed by Governor Thomas O. Moore as a major general and commander of Louisiana’s military forces until March when he accepted a Confederate Army brigadier general’s commission. After training troops in Pensacola, Fla., and southern Alabama, Bragg was promoted to major general in September. Sent to the Western Theater in 1862, he creditably led a corps under General Albert Sidney Johnston at the April 6-7 Battle of Shiloh, was promoted to full general (effective April 6), and on June 17 given command of the Western Department (including the Army of Mississippi—renamed the Army of Tennessee in November).

Prior to the Battle of Chickamauga, Bragg led his army in two battles whose longterm outcomes revealed his and his principal subordinates’ inability to turn tactical victories (or near-run “draws”) into strategic success. After winning a narrow tactical victory over Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio at the October 8, 1862, Battle of Perryville in the key border state of Kentucky, Bragg withdrew all his forces to Tennessee, handing Buell a crucial strategic win. In what became an ominous pattern, several of Bragg’s subordinates severely criticized his leadership, prompting Davis to summon him to Richmond to explain his actions, though ultimately retaining Bragg in command.

Bragg repeated his disappointing performance at the 1862-63 Battle of Stones River (Murfreesboro, Tenn.) against Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland—a tactically inconclusive draw that again found Bragg retreating. As at Perryville, Bragg was severely criticized by several subordinates in Stones River’s wake, notably Lt. Gens. Polk and William Hardee, and Maj. Gens. John C. Breckinridge and Benjamin F. Cheatham. Polk petitioned Davis, a fellow West Pointer from the late 1820s, to remove Bragg. Davis reportedly wanted Joe Johnston to replace him, only to have Johnston decline. Hardee was sent away (missing Chickamauga), but Breckinridge, Cheatham, and especially Polk remained thorns in Bragg’s side.

Not only did Bragg abandon Stones River to Rosecrans, he unaccountably left Union forces unmolested for six months, giving them time to rest, reorganize, and resupply. When “Old Rosy” finally moved, he befuddled Bragg’s off-balance army during the stunning Tullahoma Campaign (June 24-July 3, 1863). By rapidly outmaneuvering Bragg’s forces, Rosecrans suddenly had the Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga’s gates. Rosecrans’ brilliant display of maneuver, flanking marches, and feints and deceptions quickly propelled his army 100 miles forward from Murfreesboro to Chattanooga. Caught off-guard, Bragg retreated into northern Georgia and Alabama. Moreover, Rosecrans’ army was not the only Union force Bragg faced—Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s Army of the Ohio, then forming to threaten Knoxville and eastern Tennessee, forced Bragg to guess how best to meet the threats.

Bragg retreated south of the swift-flowing Tennessee River, which at places was more than a half-mile wide, thereby evacuating the campaign’s strategic prize, Chattanooga, when Rosecrans’ army managed to surge across the river uncontested. Eventually, Bragg concentrated his army near LaFayette, Ga.—30 miles south of Chattanooga. By early September, Rosecrans had maneuvered the enemy army out of Tennessee and, importantly, out of Chattanooga (though Buckner still had troops facing Burnside at Knoxville).

Yet Rosecrans made a potentially fatal error—sending his three corps across the rugged mountains west of Chattanooga over three widely separated roads. By September 10, those corps were spread out more than 40 miles southwest of Chattanooga, none within supporting distance of the other. Prompt counterattacks by Bragg’s army certainly could have defeated Rosecrans’ force in detail.

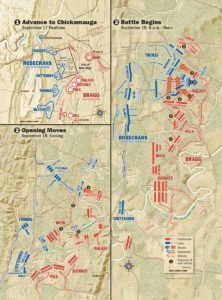

Recognizing Rosecrans’ predicament, the suddenly energized Bragg seized a “golden opportunity” on September 10 by ordering a coordinated attack on Rosecrans’ most exposed unit: Maj. Gen. James Negley’s 4,600-man division of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ centrally positioned 14th Corps (with Maj. Gen. Alexander M. McCook’s 20th Corps to the south and Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden’s 21st Corps north near Chattanooga). A half-day’s march from support, Negley sat dangerously exposed at Davis’ Crossroads.

Bragg ordered a two-division assault to annihilate Negley, with Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman’s Division (Polk’s Corps) leading the attack, supported by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s Division (Hill’s Corps). Attacking Negley from flank and front should have pushed the Union commander into a fatal cul-de-sac, but despite Bragg’s explicit orders, nothing happened. Hill prevaricated, claiming Cleburne was ill and his approach road blocked by felled trees. Bragg ordered two divisions from Buckner’s Corps to attack, but they took hours moving into position. Meanwhile, Hindman, not pressed by Polk to attack, got cold feet when Cleburne failed to appear. When an exasperated Bragg finally compelled his recalcitrant subordinates to move, Negley had been reinforced and had safely withdrawn from destruction.

Albeit belatedly, Negley’s near-miss had alerted Rosecrans to the danger his widely spread corps faced. To concentrate his men, Rosecrans frantically ordered Thomas’ and McCook’s corps to rush northeast and Crittenden’s southwest. Thus, Bragg’s best chance to destroy Rosecrans was needlessly thrown away by his insubordinate subordinates.

As Rosecrans hurried to concentrate his still-vulnerable corps southwest of Chattanooga, he gave Bragg another golden opportunity to strike a potentially fatal blow which, if successful, would regain control of all-important Chattanooga. At dawn on September 13, Bragg ordered Polk to lead a two-corps attack (his own and Walker’s Corps) to destroy Crittenden’s 21st Corps as Crittenden’s exposed flank passed along Bragg’s army’s front. Once again, nothing happened. Hours after ordering Polk to attack, but hearing no battle sounds, an incensed Bragg rode to Polk’s headquarters, discovering neither Polk nor Walker had made any attack preparations. By then it was too late. Crittenden’s corps had safely passed.

Importantly, these failed efforts to seize golden opportunities reveal Bragg’s recalcitrant subordinates had effectively rendered his hold on army command tenuous, at best.

The disputatious and authoritarian Bragg on September 15 uncharacteristically held a council of war with his principal subordinates. That conference accomplished two vital things. First, Bragg established the army’s overall tactical plan (certainly the proper one) for defeating Rosecrans—cut his army off from Chattanooga, drive it southwest, and annihilate it. Second, Bragg secured the public concurrence of all his senior commanders, making it difficult for them to justify future recalcitrance, delay, or disobedience of his orders. Whether this second accomplishment was Bragg’s principal intention cannot be known, but the council of war clearly had that effect (as Bragg’s post-Chickamauga command house-cleaning would certainly show).

The Confederates’ tactical victory at Chickamauga was due more to the valor of individual soldiers (and to Rosecrans’ egregious mistake on September 20) than to Bragg’s tactical brilliance. Indeed, the inability to get his wing, corps, and division commanders (principally Polk, but significantly others as well) to obey his orders promptly continued throughout the main battle. In fact, Bragg’s subordinates undermined and frustrated his overall tactical plan, resulting in one of the war’s most flawed “victories.”

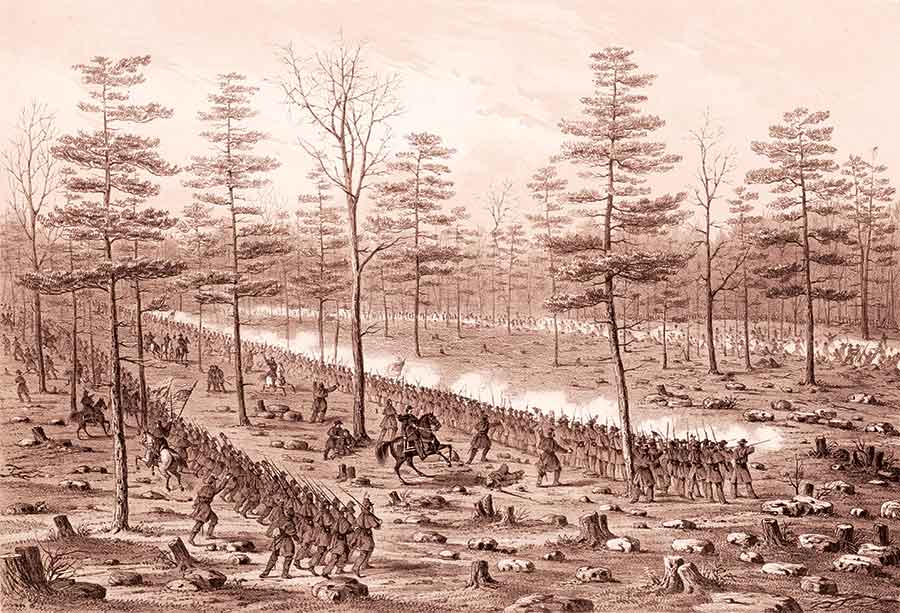

On September 18, combat erupted as the two armies faced off along both sides of the underbrush-choked West Chickamauga Creek. Bragg’s army finally made multiple crossings of the creek in the face of determined resistance by Union units. Colonel John T. Wilder’s mounted infantry “Lightning Brigade,” armed with the excellent Spencer seven-shot repeating rifles, turned back an attempt by Walker’s Corps to cross at Alexander’s Bridge. After a day of mostly inconclusive fighting, characterized by both sides fumbling in the dense woods searching for the other’s flanks, neither side had gained much advantage, although Bragg did succeed in getting his army onto the creek’s west side.

Bragg’s plan for September 19 supported his tactically sound overall plan of flanking Rosecrans on the north (the Union left) and pushing him southwest away from Chattanooga. But Bragg had badly misjudged the Union army’s northernmost positions, as Thomas’ units already had reinforced Crittenden, seizing good defensive terrain. That resulted in locally fierce attacks that by sundown had pushed Union forces west, though they still held along a strong, generally north-south line about a mile west of the creek.

Cleburne’s Division attacked shortly after sundown, gaining some ground. But no major Confederate breakthrough had been achieved. Combat ended that night in a standoff. Notably, Confederate attacks were piecemeal and none concentrated sufficient combat power to break Rosecrans’ line.

Bragg’s failure to concentrate and achieve a decisive breakthrough on September 19 was not caused simply by his misjudgment of the strength and position of Rosecrans’ left flank; instead, it was inevitably exacerbated by his flawed organization. Bragg began that day’s battle with eight subordinate corps and reserve units reporting directly to him—an impossibly large span of control to reasonably expect prompt execution, particularly given his subordinates’ demonstrated reluctance to obey. Today, only three to five subordinate units are considered the maximum number any commander—regardless of competence—can effectively control (and today’s orders are “instantly” transmitted via radio, computers, or electronics—whereas Bragg relied on junior officer couriers on horseback, hand-carrying written orders that frequently went astray, were misinterpreted, or were simply ignored by his subordinates).

Bragg, in an attempt to rectify this span of control problem, reorganized his army into two “wings” (Polk commanding the Right Wing, Longstreet the Left). Yet he failed to ensure that all of his corps commanders knew the changed command structure—for example, Hill belatedly learned he was now a subordinate in Polk’s Right Wing at 6 a.m. on September 20, and Longstreet discovered he was Left Wing commander only upon his 11 p.m. arrival at Chickamauga on September 19. Although Bragg theoretically fixed his span of control problem, he failed to implement it properly. Adding another command layer inevitably introduced more delays in transmitting his orders to the divisions executing them.

Fate, however, intervened to diminish Bragg’s command failures.

Bragg’s plan to win the battle on September 20 followed his tactically sound plan to push Rosecrans southwest and away from Chattanooga. He correctly ordered a strong daybreak attack on the Union left by Polk’s Right Wing in which eight divisions were to step off en echelon. An attack by Longstreet’s Left Wing was to follow. Understandably, Longstreet spent hours the morning of September 20 familiarizing himself with the battlefield, attempting to place his divisions in proper order, and preparing his units to attack. Yet Polk once again frustrated Bragg’s intent by unaccountably delaying the Right Wing’s attack. In fact, when Bragg rode to Polk’s headquarters in late morning to find out why the attack had not been launched at dawn, as ordered, he found Polk calmly eating breakfast. With Longstreet still sorting out his own units, nothing in Bragg’s plan was going right. That would change about 11 a.m.

Perceiving a dangerous—though nonexistent—“gap” in his front line, Rosecrans jumped the chain of command and directly ordered Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood of Crittenden’s 21st Corps to withdraw his division from the front line and immediately reposition it farther north. Wood realized the order was a mistake, but complied—with disastrous consequences.

Finally prepared to attack, 10,000 men—led by Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s Provisional Division, of Hood’s Corps in Longstreet’s Left Wing—advanced across the Brotherton Farm and hit the gap in the Union line just vacated by Wood’s division. In that instant, Rosecrans lost the Battle of Chickamauga but not, as it turned out, the strategic prize of Chattanooga.

Johnson’s troops, followed closely by those of two other divisions, poured through the gap, fatally collapsing the Union line and nearly overrunning Rosecrans’ headquarters. Fully one-third of Rosecrans’ army fled toward Chattanooga as Bragg’s Confederates swept them along in disarray. Yet letting the Yankees flee toward Chattanooga was the last thing Bragg wanted. Instead of cutting off Rosecrans’ army from the strategic city and driving it to the southwest and utter destruction, Polk, by failing to attack vigorously on the north, produced the opposite result. Longstreet’s dramatic breakthrough merely pushed Rosecrans’ defeated army north to the safety of Chattanooga.

Despite Polk’s failure to implement attack orders on the right flank, Bragg’s army had won a stunning tactical victory. But again, due to Polk’s abysmal failure, the victory proved incomplete as Thomas rallied his corps and other Union units in a last stand on Snodgrass Hill/Horseshoe Ridge that prevented the annihilation of the Federal army. Perhaps convinced that Johnson’s breakthrough had secured victory, Longstreet did not strongly press his advantage to destroy Thomas’ Snod-grass Hill defense, leaving this significant roadblock in position.

Seething that his overall plan was coming apart, Bragg summoned Longstreet to his headquarters and demanded action while also exclaiming in frustration at Polk’s continued incompetence: “There is not a man in the right wing who has any fight in him!” Longstreet, found calmly eating a lunch of yams and bacon, was taken aback and belatedly turned his attention to Thomas’ stubborn defense.

Longstreet reported launching 25 separate assaults on Thomas’ Snodgrass Hill defenses on September 20. Thomas’ stand, which famously earned him the nickname “Rock of Chickamauga,” saved Chattanooga for the Union. It allowed Rosecrans time to rally his defeated army inside the city’s defenses while helping dissuade Bragg from launching a vigorous pursuit that could have cut off the Federals before they passed safely into the city. Had Polk not disobeyed Bragg’s orders by unaccountably delaying his September 20 attack, Thomas’ defense would never have materialized.

The Breaking Point

None of Braxton Bragg’s poor subordinate relations matched the one he had with the fiery Nathan Bedford Forrest. In the days or weeks after Chickamauga—when exactly has not been substantiated—Forrest reportedly confronted Bragg, angry that Bragg had halted pursuit of the beaten Federals at the end of the battle. According to a possibly apocryphal story by regimental surgeon J.B. Cowan, Forrest snarled, “You…are a coward….You may as well not issue any orders to me, for I will not obey them….If you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life.”

Only Nathan Bedford Forrest seemed eager to press Rosecrans’ fleeing army and annihilate it, realizing that any tactical victory at Chickamauga was meaningless for Confederate fortunes if Chattanooga remained in Union hands. After his cavalrymen fought brilliantly as dismounted infantry on Bragg’s northern flank, Forrest launched a vigorous pursuit, capturing hundreds of fleeing Federals while attempting to cut off Rosecrans’ retreat. But Bragg, as he had done with other commanders at Perryville and at Stones River, proved unwilling to support Forrest. Claiming that the Army of Tennessee was “exhausted” and “lacked wagons and transport,” Bragg exerted no effort to block the Union withdrawal (eliciting the disgusted Forrest’s exclamation, “What does [Bragg] fight battles for?”).

Frustrated time and again by his recalcitrant subordinates in his effort to win a decisive victory at Chickamauga—but himself unwilling to launch a spirited pursuit once Rosecrans’ army began to flee—Bragg settled for besieging Chattanooga. The command chaos plaguing the Army of Tennessee during the Chickamauga Campaign continued. On September 29, Bragg dismissed both Polk and Hindman. Next, on October 4, a dozen of his senior subordinates signed a letter to Davis (likely authored by Buckner) demanding Bragg’s relief (Longstreet similarly wrote Secretary of War James Seddon). Davis arrived October 9 at army headquarters, interviewed Bragg’s disgruntled subordinates, and again backed Bragg. Davis’ support prompted Bragg to relieve three more subordinates who had signed the letter: Hill (effectively demoting him to major general) and both Walker and Buckner (each relegated to division command). Meanwhile, Longstreet and his corps departed for Knoxville to face Ambrose Burnside’s Union army, and Forrest, at his own request, transferred to Mississippi.

Bragg’s army command tenure finally ended after the Chattanooga debacle. On December 1, he asked to be relieved and this time his request was accepted. Bragg went east for the war’s remainder, first as Davis’ military adviser ( Bragg, predictably, quarreled with senior CSA officials) and later leading division-sized units during the Carolinas Campaign. After the war, Bragg found minor civilian success, briefly holding jobs in Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas but, inevitably, arguing with his bosses before moving on. On September 27, 1876, Bragg died, probably of a stroke, in Galveston, Texas. He was 59 years old.

Edwin L. Kennedy Jr. is a 1976 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, retired U.S. Army infantry lieutenant colonel and former professor at the U.S. Army Command & General Staff College’s History Department and Combat Studies Institute. Since 1994 he has led countless staff rides, including ones of the Battle of Chickamauga.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.