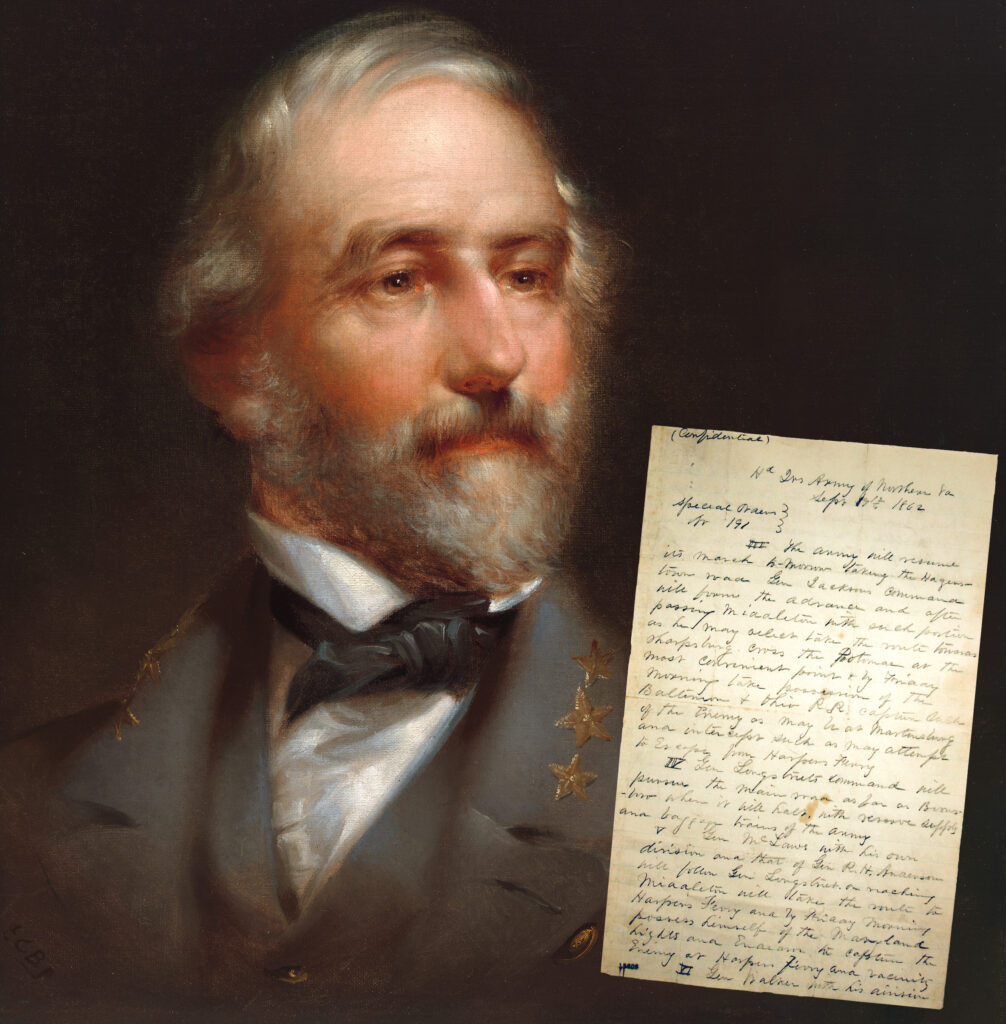

Debate about the importance of the loss of Robert E. Lee’s Special Orders No. 191 to the outcome of the September 1862 Maryland Campaign has long revolved around the response of Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan upon reading the document found by a Federal soldier outside Frederick, Md., on September 13. To those in agreement with the thesis proposed by authors such as Stephen W. Sears, the so-called “Lost Orders” provided McClellan with potentially war-winning intelligence that he duly squandered through excessive indecision. Conversely, to those who prefer fellow historian Joseph L. Harsh’s interpretation, McClellan gained little useful information in the Lost Orders, principally because the Federal commander had already begun pushing troops west from Frederick in pursuit of Lee’s army before the document passed into his hands.

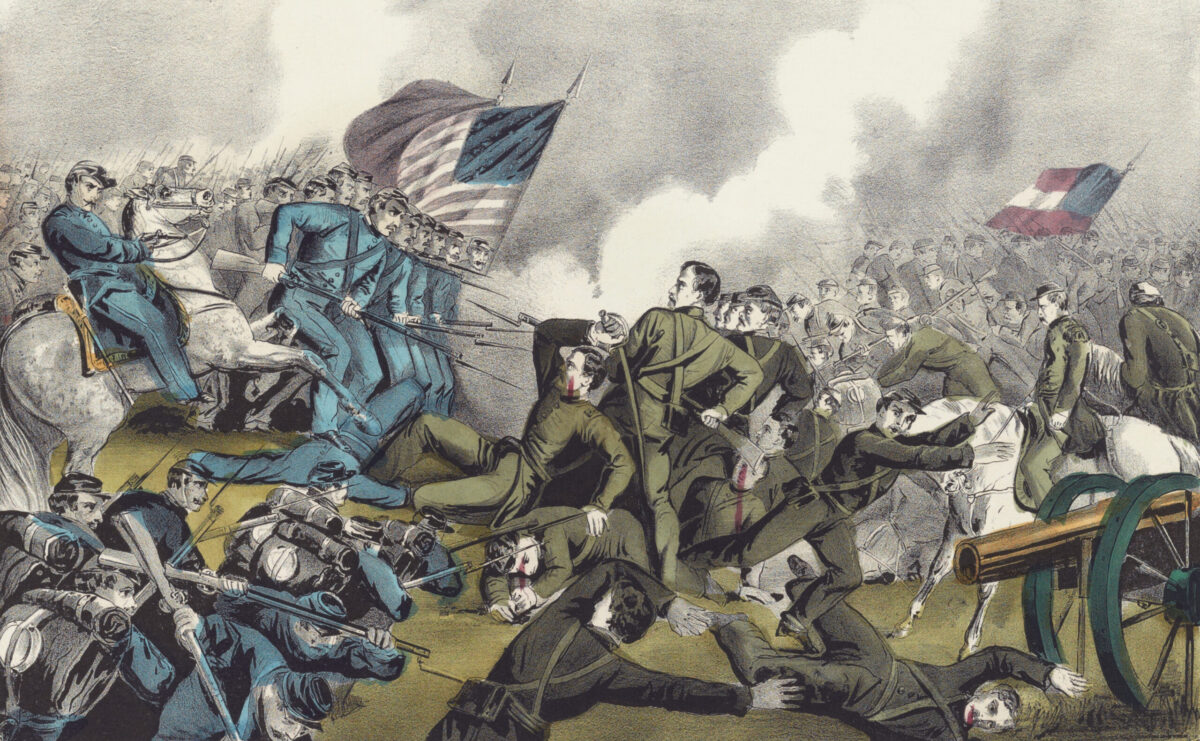

The merits of these arguments notwithstanding, neither takes into account the impact that McClellan’s actions had on Confederate operations from September 14 onward. When considered from this point of view, it becomes clear that McClellan’s assault on the South Mountain gaps had three significant effects: It ruined Lee’s plan for the campaign after the capture of Harpers Ferry, Va.; it forced Lee to take up a less than favorable ad hoc defensive position at Sharpsburg; and it weakened the Army of Northern Virginia’s combat strength in the days leading up to the clash there on September 16-17.

According to Paragraph IX of Special Orders No. 191, Lee desired that following the fall of the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry, “The commands of Generals Jackson, McLaws, and Walker, after accomplishing the objects for which they have been detached, will join the main body of the army at Boonsborough or Hagerstown.” Why Lee envisioned reassembling his army in the middle of Maryland’s Washington County is explained by his overall strategy for waging war in the state. After initially seeking to instigate a popular rebellion north of the Potomac River, Lee learned from Confederate sympathizers in Frederick City that it was likely no uprising would take place until martial law in the state had been lifted. The arrest of prominent Secessionists and the seizure of private property by Federal authorities had convinced those aligned with the South that they could never successfully resist the national government’s occupation forces unless Lee’s army could defend them. The general noted this belief in his August 1863 campaign report, writing, “The difficulties that surrounded them [Maryland’s Secessionists] were fully appreciated…[and] we expected to derive more assistance…from the just fears of the Washington Government than from any active demonstration on the part of the people, unless success should enable us to give them assurance of continued protection.”

A second source echoes Lee’s statement, this one penned by British army officer (and later Field Marshal) Garnet Joseph Wolseley. Visiting the Army of Northern Virginia in mid-October 1862, Wolseley wrote: “It is generally stated that the Confederate authorities calculated upon a rising in Maryland directly [when] their army entered that state. Everybody to whom I spoke on the subject ridiculed the idea…that any such rising would take place, until either Baltimore was in their hands, or they had at least established a position in that country.”

Wolseley’s comment confirms two things. First, it reinforces the conclusion that the policy of entering Maryland to test the strength of secessionist sentiment came from “Confederate authorities” in Richmond. This means that Robert E. Lee did not act on his own when he took his army across the Potomac. He was carrying out an official policy of the Confederate government. Second, Wolseley’s comment makes it clear that many of the officers with whom he spoke shared Lee’s belief their army could encourage an uprising in Maryland only if it won a victory (i.e., “established a position in the country”) or if it marched on and seized Baltimore.

In response to the reluctance of Maryland’s people to rise up, Lee took steps to reassure those who might be inclined to support the South. He instructed Charles Marshall to compose a proclamation explaining the reasons for the Army of Northern Virginia’s presence in the state and, after learning on September 8 that the Federal garrison remained in place at Harpers Ferry, he designed Special Orders No. 191 to capture it. Lee also learned on September 8 that a new army under the command of McClellan had begun advancing toward Frederick.

In view of this oncoming threat, Lee hoped that Jackson and the others detached for the operation could quickly seize the ferry and then rejoin Longstreet’s command for a decisive battle with McClellan’s force. A slight alteration Lee made to this plan on September 11 included marching a portion of the army toward Hagerstown (and Pennsylvania) to “induce the enemy to follow” west of South Mountain. This maneuver substantiated a statement attributed to Lee that appeared in the September 12 issue of The Philadelphia Inquirer which held that “the battle ground must hereafter be in Maryland” if the state’s people failed to rebel.

Once he arrived west of South Mountain, Lee intended to confront McClellan on ground of his choosing. There he could crush the Army of the Potomac far from the protection of the Washington defenses and achieve the potentially war-ending victory that had eluded him at Second Manassas. Lee therefore chose the heights along a small watercourse called Beaver Creek as his preferred battleground. Anchored in the southwest by rough terrain along Antietam Creek, and ranging as tall as 560 feet in elevation, this undulating ridge line runs east-northeast nearly to the base of South Mountain. The Beaver Creek heights offered Lee a strong position that would be difficult, although not impossible, for an enemy to flank if it was occupied by a determined defender.

Wrecked Plans

Multiple sources confirm the general’s desire to defend the Beaver Creek line. These include a dispatch Lee sent to Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws on the evening of September 13, after he learned from Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill that a powerful enemy column had appeared at the eastern foot of South Mountain. Telling McLaws, “General Longstreet will move down [from Hagerstown] to-morrow,” Lee added that Longstreet’s men would “take position on Beaver Creek this side of Boonsborough.”

The following morning, according to the war reminiscences of Angela Kirkham Davis, a New York–born woman residing in Funkstown, Md., Lee issued a warning to the people of her village, located some four miles behind Beaver Creek. Lee advised them to flee from the fight he believed was about to take place in their midst. Then Lee spoke to his artillery chief, Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton, about the Beaver Creek position later that day. Pendleton recalled this in his campaign report, stating that on “Sunday morning, 14th, we were summoned to return toward Boonsborough, the enemy having advanced upon General D.H. Hill. When I arrived and reported to you [General Lee] a short distance from the battle-field, you directed me to place in position on the heights of Beaver Creek the several batteries of my command.” Pendleton’s report demonstrates that even as the Battle of South Mountain raged Lee hoped to fall back to his chosen position along Beaver Creek.

Sources also show that contrary to claims made by Lee and Longstreet after the campaign about departing from Hagerstown at daybreak to reinforce Hill atop South Mountain, Longstreet’s reduced command of eight brigades (Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs’ brigade remained at Hagerstown) and the independent brigade of Brig. Gen. Nathan “Shanks” Evans did not get on the road until after the fighting at South Mountain began around 8 a.m. Lee clinging stubbornly to his Beaver Creek plan would account for this delay because, as the general himself later wrote, “It had not been intended to oppose [the Federal army’s] passage through the South Mountains, as it was desired to engage it as far as possible from its base.”

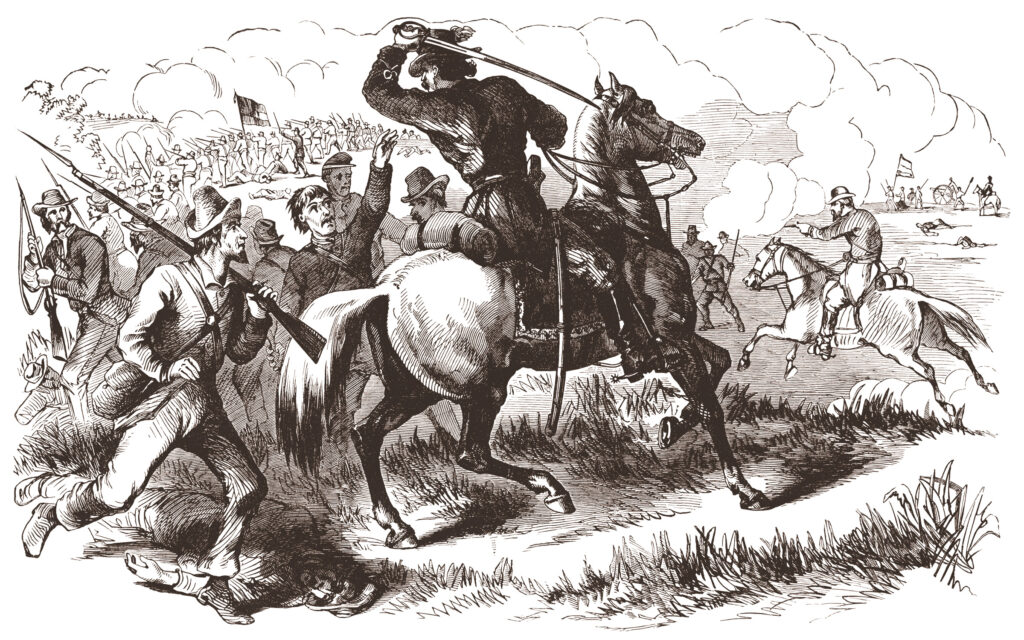

McClellan’s army “advancing more rapidly than was convenient from Fredericktown” wrecked these plans for Lee by forcing him to defend the South Mountain passes. Doing so placed the Confederate commander in a difficult position. Unfamiliar with the terrain atop the mountain, and too disabled by injuries incurred during an accident at the end of August to ride a horse, Lee could not personally direct his army’s defense of the mountain passes. The situation five miles south at Crampton’s Gap proved even more headache-inducing as its defense remained entirely beyond the general’s control.

Consequently, three major outcomes resulted from McClellan using the information he learned in the Lost Orders: He attacked the South Mountain gaps; he forced Lee to abandon the favorable defensive position he had chosen; and he compelled Lee to defend ground on South Mountain that the Confederate general neither knew nor planned on defending in the first place.

A Less Favorable Position

The rapidity of McClellan’s unexpected advance knocked Lee off balance. Not only did the defeat at South Mountain then force Lee to fall back in the direction of Virginia, but it also called into question where, or even if, the general could salvage his plan to fight north of the Potomac. After all, Jackson’s siege of Harpers Ferry remained underway with Lee ignorant of when it might be concluded. The hope expressed by Special Orders No. 191 was that Jackson could compel the garrison’s surrender by Sunday, September 14, at the latest. On the morning of September 15, however, Lee found himself still oblivious to Jackson’s progress. For a short time overnight on September 14, Lee even considered returning to Virginia, writing to McLaws after learning of the Federal victory at Crampton’s Gap: “The day has gone against us and this army will go by Sharpsburg and cross the river.”

Then, at about 8 a.m. on September 15, a note from Jackson finally made its way to Lee, stating that he anticipated the enemy would surrender Harpers Ferry in short order. Receiving this note in the vicinity of Keedysville breathed new life into Lee’s faltering operation and he quickly sought ground on which to fight the battle he had envisioned fighting at Beaver Creek. This ground he found on the far side of Antietam Creek, and although Lee did not say it, the terrain there resembled the Beaver Creek position to a degree. With heights as tall as 500 feet above sea level between the creek and Sharpsburg, Lee found a position closer to Jackson in (West) Virginia that was on the flank of Lafayette McLaws’ position in Pleasant Valley, and which looked similar to the one he had originally intended to occupy several miles to the north.

Yet unlike the Beaver Creek position, Antietam Creek and the heights in front of Sharpsburg anchored only the center and far right of the Confederate line. Rolling countryside bisected by low ridges and peppered with woodlots characterized the terrain on the Confederate left flank. This ground proved to be defensible, but South Mountain did not hem in the position there as it did along Beaver Creek. Putting numbers to this equation, the distance between the eastern end of the Beaver Creek heights and the western slope of South Mountain near the small community of San Mar is approximately 1,056 yards or 0.6 miles—equaling a battlefront just under three Civil War–era brigades in length.

North of Sharpsburg, the distance from the creek to farmer David Miller’s soon-to-be-immortal cornfield—where the bulk of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s attack fell the morning of September 17—is 2,816 yards or 1.6 miles. That equaled a front line more than two divisions long, meaning McClellan could maneuver a larger number of troops against the Confederate left than he would have been able to had Lee managed to defend the Beaver Creek heights. The resulting stand-up fight at Sharpsburg thus proved to be less to the benefit of the smaller, numerically weaker Army of Northern Virginia and more to the advantage of the larger Army of the Potomac.

Fighting at the Beaver Creek position also would have provided Lee with a battlefield accessible by multiple entry and exit points to the rear. With only a single road and a rocky ford across the Potomac behind him at Sharpsburg, even Lee judged the position to be “a bad one” by comparison. Arguably, therefore, this secondary field on which Lee chose to fight proved to be substantially less favorable to his army and more favorable to the enemy than the position he had initially hoped to take. Although he did not know it, McClellan’s attack at South Mountain, informed by what he had learned in Special Orders No. 191, effectively negated the battlefield advantage that Lee had sought to achieve in Washington County.

Depleted Strength

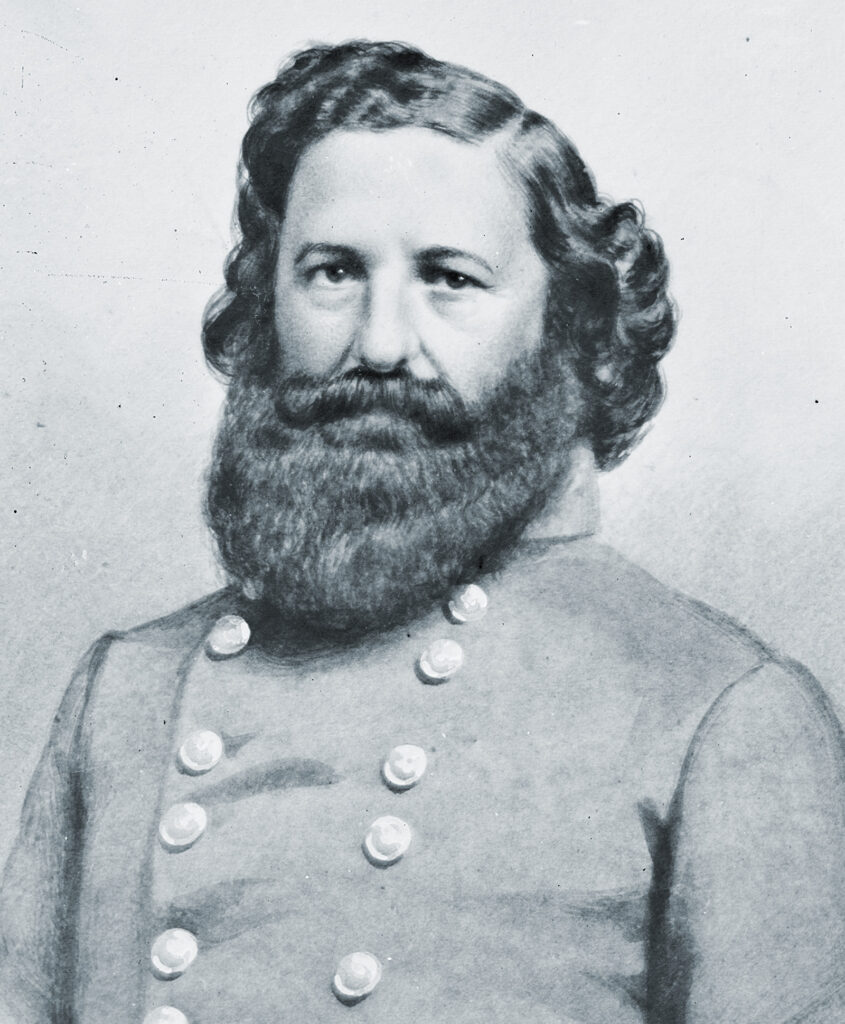

McClellan’s attack on the South Mountain gaps created yet another knock-on effect detrimental to the Army of Northern Virginia—it compelled Lee to reassemble his army before either he or it was prepared. This resulted in a loss of combat strength when the fight at Sharpsburg broke out. The experiences of Longstreet’s command on September 14 and, to a lesser extent, of McLaws’ command on September 16-17 are instructive here. Informed estimates put Longstreet’s effective strength at approximately 7,800 men when his command made its forced march from Hagerstown on the morning of September 14. This march, made mostly on the quick, and even the double-quick (i.e., jogging), proved too taxing for many men to take, particularly those of Old Pete’s troops who lacked footwear. Consequently, when Longstreet reached the top of South Mountain, D.H. Hill estimated that his command “did not exceed four thousand men.” It is unknown how many of these men later caught up with the army on its march to Sharpsburg, but they were not available for at least the defense of Turner’s and Fox’s Gaps, clashes that caused significant casualties and resulted in a decisive Confederate reverse. Their experience illustrates the chaos into which McClellan’s sudden advance threw the Army of Northern Virginia.

McLaws’ situation provides a similar example. Detached from the rest of the army with Richard H. Anderson’s Division to besiege Harpers Ferry on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, McLaws’ Division suffered severe losses from straggling in the run-up to Sharpsburg. According to one strength estimate provided by John Owen Allen, 7,337 men comprised the four brigades of McLaws’ Division as of September 2. By September 13, this number had dropped to an estimated 3,778 men available for duty, meaning that while in Maryland, and even before the engagement at Crampton’s Gap the following day, 48.5 percent of McLaws’ men had abandoned the army.

The fights atop Maryland Heights and at Crampton’s Gap further depleted McLaws’ strength by another 929 men and officers killed, wounded, or missing/captured. Then, on the afternoon of September 16, Lee, scrambling desperately to reassemble his scattered army so that he could fight above the Potomac and achieve the “military success” that he hoped would encourage Marylanders to rebel, called McLaws from Harpers Ferry to Sharpsburg. The Georgian made a forced march that night which further reduced his strength by another 7.7 percent, or 220 men (probably an underestimate), leaving McLaws with only 2,629 effectives for the battle on September 17.

This overnight march must have been severe. To quote McLaws himself, “The straggling of men, wearied beyond further endurance, and of those without shoes and of others sick was very great, which accounts for the small force carried into action. But by the evening of the 18th most of the absentees had joined and my force was nearly as large as that I had carried into action on the 17th, although I had lost heavily in killed and wounded.” Brigadier General William Barksdale, whose four regiments of Mississippians marched with McLaws, recalled similarly, “a portion of my men had fallen by the wayside from loss of sleep and excessive fatigue, having been constantly on duty for five or six days, and on the march for almost the whole of the two preceding nights…I went into the fight with less than 800 men.”

Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw, a South Carolinian commanding a brigade in McLaws’ Division, reported that his men “were also under arms or marching nearly the whole of the nights of Monday and Tuesday, arriving at Sharpsburg at daylight on Wednesday morning, September 17…[M]any had become exhausted and fallen out on the wayside, and all were worn and jaded.” An unidentified soldier with the 8th Alabama, a part of Col. Alfred Cummings’s brigade in R.H. Anderson’s division agreed, calling the march to Shepherdstown “trying in the extreme.” Lastly, recalled James Dinkins of the 18th Mississippi:

“About daylight we reached Shepardstown [sic] on the Potomac river, and crossed over to the Maryland side, but we crossed with a small proportion of the command which began the march. We remember that Company ‘C,’ Eighteenth Mississippi, left Harper’s Ferry with over sixty men and three officers, but we went into the battle of ‘Sharpsburg’ with sixteen men and one officer. Other companies, of course, suffered similar dimunition. The march was one of the severest ever made by infantry troops.”

One cannot help but wonder what a difference it would have made to the Battle of Antietam if Lee had possessed more time to reassemble his army. Licensed Antietam battlefield guide Russell Rich argues in a 2022 study of Confederate straggling during the campaign that the loss of so many troops prior to Antietam did not diminish the combat effectiveness of Lee’s army on the battlefield. This conclusion seems to say more about the fighting prowess of veteran Confederate troops than it does about the army’s thin ranks. It cannot be ignored that Lee sought multiple times to launch an attack on the Federal right flank both during and after the fight at Antietam. A lack of available space due to a bend in the Potomac River and McClellan’s massing of artillery on that flank contributed to the maneuver’s failure, but Lee scarcely being able to muster 5,000 men for the endeavor also proved to be a key deficiency.

At no point on September 17 were Lee’s men able to recover the ground they lost in the early hours of the struggle. Counterattack certainly, and this Lee did, but recover their original lines or drive the Federals back to Antietam Creek, never. The battle thus ended as a Confederate defeat precisely because Lee did not have the men he required for an effective offensive, and he did not have the men because straggling significantly reduced the number present for action. This material weakness then persisted until the following day when Lee retired to Virginia because McClellan’s army had received reinforcements while Lee’s had not. The general summarized this situation in his campaign report, writing, “As we could not look for a material increase in strength, and the enemy’s force could be largely and rapidly augmented, it was not thought prudent to wait until he should be ready again to offer battle.” Systemic weakness caused by straggling, and exacerbated by high combat losses, forced Robert E. Lee to abandon his campaign and the effort to bring Maryland into the Confederate fold.

Even before McClellan’s unanticipated advance on September 13-14, Lee had complained to Jefferson Davis about straggling’s devastating effect on his army: “One great embarrassment is the reduction of our ranks by straggling, which it seems impossible to prevent with our present regimental officers. Our ranks are very much diminished I fear from a third to one-half of the original numbers.” The threat posed by McClellan’s advance then intensified the problem by causing Lee’s men to engage in a series of forced marches to rejoin the army in Maryland. By the time the clash erupted at Sharpsburg, Lee’s army—numbering between 50,000 and 70,000 men at the campaign’s outset, according to some estimates—had lost a crippling number of stragglers.

Straggling during the campaign angered Lee so much, in fact, that he complained about it in a missive to Jackson and Longstreet on September 22. Implementing a series of reforms at this point, including daily roll call, the creation of a permanent provost guard, and increased efforts by field officers to observe and account for the presence of their men, General Lee made sure that service in the Army of Northern Virginia became much more rule-bound after Sharpsburg than it had been to that point.

Quantifying the full extent to which men falling out of the ranks weakened the Army of Northern Virginia is probably impossible, although we can arrive at a reasonable estimate. To quote Darrell L. Collins’ summary of Confederate strength on September 30, less than two weeks after the epic battle, Lee’s army counted 52,189 men in its ranks. Compared to the fewer than 40,000 men with which Lee and others claimed to have fought the battle, one can only imagine what the outcome might have been had the Confederate commander possessed this additional 12,000 troops on September 17. It is doubtful that elements of the Union 2nd Corps would have penetrated the Confederate center as they did at the Sunken Road if Longstreet had another 5,000 men to throw into the fight. Similarly, Ambrose Burnside probably would not have been able to drive in Lee’s right flank if Jacob Cox’s 9th Corps had faced 3,000 men defending the heights above Antietam Creek instead of Colonel Henry L. Benning’s “little over four hundred.” Possessing an additional 4,000 men would have also given Lee the men he needed for the attack on the Federal right for which he ached so badly.

“At Great Disadvantage”

The examples of Longstreet on September 14 and McLaws on September 17 suggest that the hard marches forced by McClellan’s rapid advance contributed to reducing the number of combat effectives available to Lee by a sizable margin. D.H. Hill shared this viewpoint, stating, “Had all our stragglers been up, McClellan’s army would have been completely crushed or annihilated.” Combine the army’s decimation with it being compelled to fight on ground more favorable to the Federals than the position Lee first chose and a more urgent sense of the damage caused to the Confederate operation by the loss of Special Orders No. 191 becomes clear. Writing to Hill in February 1868, Lee referred to the loss of the orders as “a great calamity and subsequent reflection has not caused me to change my opinion.” From ruining Lee’s plan to fight along Beaver Creek and forcing him to defend the South Mountain passes, which itself caused significant casualties, to giving the Federals a more advantageous place to fight and reducing Confederate strength by pressing the army to reassemble on the quick, one cannot help but agree with Lee’s characterization of the orders’ loss as a disaster.

On February 15, 1868, the general himself told William Allan, an Army of Northern Virginia veteran and one of its earliest historians: “Had the Lost dispatch not been lost, and had McClellan continued his cautious policy for two or three days longer, I would have had all my troops reconcentrated on [the] Md. side, stragglers up, [and] men rested.”

Charles Marshall echoed this sentiment, writing in his war memoir that “Instead of being united and fresh as it would have been had General McClellan continued his slow rate of advance for twenty-four hours longer, as there is reason to believe he would have done but for the loss of the order…[the army] had to engage the enemy at great disadvantage.”

Longstreet’s men and those under D.H. Hill, Marshall continued, “went into the battle [at Sharpsburg] under the disheartening effects of the disaster at Boonsboro,’ and considerably reduced in number by that engagement, while those of General Jackson had to make a long march in intensely warm weather and go into battle without opportunity for necessary repose and refreshment.

“In considering the Maryland campaign, it is proper to take into account the effect of the accident of the lost order upon the result—a misfortune that was not incident to the plan of campaign, although it had a most important influence upon the result….The effect of the loss of that order does not show any want of wisdom or prudence in the policy of the invasion of Maryland in 1862. But for that, no battle need have been fought at Sharpsburg, or at South Mountain, or anywhere except at a time and upon terms of General Lee’s own selection.”

Supposing Marshall is correct, and taking into account Robert E. Lee’s own estimate of the harm caused to his operation by the loss of Special Orders No. 191, one cannot reasonably conclude other than to say that the discovery of the mislaid document by Private Barton Mitchell about noon September 13 contributed mightily to the Confederate defeat in Maryland. For that the credit must go to George McClellan, whose actions forced Lee into a difficult situation for which he was ill prepared, and who by doing so saved the republic when it faced the possibility of a terrible defeat that might have ended it for good.

Alexander Rossino writes from Boonsboro, Md. This article is adapted from his latest book, Calamity at Frederick (Savas Beatie, 2023).