At the time, it seemed like such a good idea.

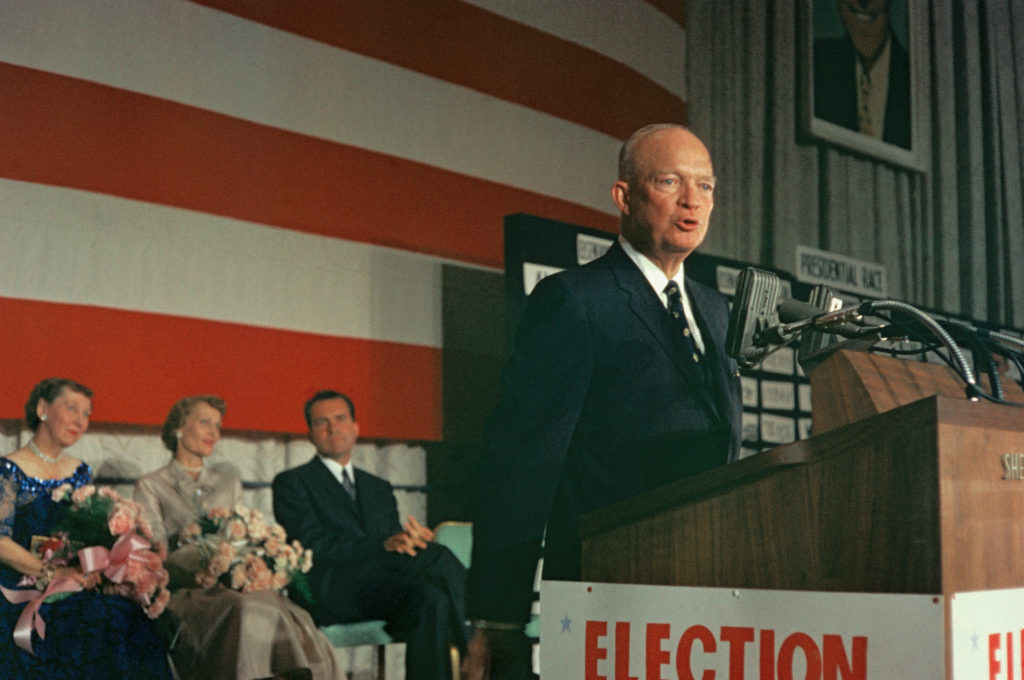

In 1947, congressional Republicans, still smarting from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s unprecedented wartime re-elections to a third and then a fourth term, undertook to see that no American chief executive could try that again. Their campaign bore fruit in 1951 — but less than a decade later the GOP was feeling constitutional amender’s remorse. Dwight Eisenhower, ending a second successful term as president, stood in 1960 to be a shoo-in for a third term — but for his own party’s boomeranging activism.

The Founding Fathers’ Thoughts on Term Limits

At the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the framers wrestled with how long a president should serve. Alexander Hamilton proposed a presidency for life. Skeptics saw no merit in a de facto monarchy. Presidents are the servants of the people, Benjamin Franklin noted: “It would be imposing an unreasonable burden on them, to keep them always in a State of servitude, and not allow them to become again one of the Masters,” the wry Franklin said.

Some delegates wanted a single six- or seven-year term. Others favored a briefer tenure with eligibility for multiple terms. New York’s delegation proposed allowing a second term, period. The convention settled on a four-year term with no ban on running again. The Constitution did not prevent a president from seeking as many terms as he might want, but of the office’s first three holders, two adhered to an informal two-term limit that came to be embraced so strongly as custom as almost to carry the force of law. In 1796, George Washington declined to seek a third term but did not condemn the concept.

“I can see no propriety in precluding ourselves from the services of any man, who on some great emergency, shall be deemed, universally, most capable of serving the Public,” he wrote.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Absent urgent need, however, Washington thought a president seeking a third term could find himself harped at for “concealed ambition.”

In 1808, his second term ending, Thomas Jefferson, following what he called “the sound precedent set by an illustrious predecessor,” declined to run again.

“Reason and experience tell us that the first magistrate will always be reelected, if he may be reelected,” Jefferson wrote to James Madison. “He is then an officer for life.”

Like Washington, Jefferson saw the point of making an exception in times of national peril, but absent a crisis, “should a President consent to be a candidate for a 3d. election, I trust he would be rejected on this demonstration of ambitious views,” the author of the Declaration of Independence wrote.

Term Limits in the 19th Century

Some early presidents thought one term enough — then thought again. In 1829, Andrew Jackson told Congress, “I can not but believe that more is lost by the long continuance of men in office than is generally to be gained by their experience.” In 1832, Jackson ran anyway.

In his 1841 inaugural address, William Henry Harrison promised that “under no circumstances will I consent to serve a second term” — a matter mooted when Harrison died after less than a month in office, the shortest term in American presidential history.

Seceding in 1861, Southern states also broke with the Union on presidencies, granting the Confederacy’s leader one six-year term — although the Confederacy expired before Jefferson Davis’s term did.

Term limits arose again under Ulysses S. Grant. The former general, poised to be the first president since Jackson to complete two terms, was said to be considering running for a third term when, in December 1875, the House overwhelmingly passed a resolution aimed at Grant condemning that possibility. The two-term limit had become “by universal concurrence a part of our republican system of government,” Congress said. “Any departure from this time-honored custom would be unwise, unpatriotic, and fraught with peril to our free institutions.” Grant did not run in 1876. In 1880, he pursued but was denied the Republican nomination.

In 1884, Grover Cleveland urged a constitutional amendment limiting presidents to one term, because, Cleveland said, eligibility for reelection constitutes “a most serious danger to that calm, deliberate, and intelligent political action which must characterize a government of the people.” Even so, Cleveland sought a second term in 1888. He lost to Benjamin Harrison but ran again, successfully, in 1892, the only American president to serve nonconsecutive terms.

Here Come the Roosevelts

For 153 years, no president elected to two terms was nominated for a third, though Theodore Roosevelt came close. Elected in 1904 after serving three-quarters of the assassinated William McKinley’s term, Roosevelt refused to run in 1908. In 1912, he sought a second term representing a third party. That display of “unconcealed ambition” prompted John Schrank to wound Roosevelt with a shot from a pistol at a Milwaukee campaign stop.

“Any man looking for a third term ought to be shot,” said Schrank, later judged insane.

In 1940, World War II forced Franklin Roosevelt to confront term limits and national peril. The cagey FDR, elected in 1932 and 1936 [https://www.historynet.com/landslide-fdr-reelection-new-deal/], said he had no plans to seek a third term. By midyear, with the European Allies on the ropes, the nation about to unveil its first peacetime draft and combat crowding the headlines, the United States seemed destined to fight Germany — but Roosevelt refused to tip his hand.

Suspense built as Chicago prepared to host the July 1940 Democratic National Convention. From Washington on July 16, Roosevelt relayed a message to the convention, declaring he had no wish to run again — but never declaring he would not accept a nomination — and he released delegates pledged to him. A raucous “We Want Roosevelt” demonstration triggered a carefully orchestrated “spontaneous” draft. In the wee hours of July 18, the convention nominated FDR by acclamation.

“Today all private plans, all private lives have been repealed by an over-riding public danger,” Roosevelt said in his acceptance speech. “In the face of that public danger all those who can be of service to the Republic have no choice but to offer themselves for service in those capacities for which they may be fitted.”

Opponent Wendell Willkie pounced, referring to FDR not by name but as the “third-term candidate.” The Republican called his rival’s bid to stay in the White House “the last step in the destruction of our democracy,” pledging that if elected he would seek a constitutional amendment limiting presidents to two terms. Roosevelt stomped Willkie by nearly 5 million votes, carrying 38 states to his competitor’s 10.

In July 1944, the Democrats nominated Roosevelt for a fourth term. FDR, now frail and failing, accepted, “based solely on a sense of obligation.” Foe Thomas E. Dewey hammered at Roosevelt’s stretch at the helm.

“In the name of those who are fighting and dying in the cause of freedom, we dare not risk leaving this vital labor in the hands of those who have grown tired and quarrelsome from 12 years in office,” the New York governor railed.

But voters liked the idea of a president serving for the duration, as millions in uniform were doing. Carrying 36 states to Dewey’s 12, FDR cruised to victory. Five months later, he was dead.

Recommended for you

Willkie’s Revenge

In 1947, the Republicans, now holding sizeable majorities in Congress, moved to make good on Willkie’s term limit vow. They faced a daunting drill. To change the Constitution, the House and the Senate must draft and approve, each by a two-thirds vote, a proposed amendment that becomes law only if three-quarters of the states ratify it with a certain time limit.

On Jan. 3, 1947, the first day of the 80th Congress, Rep. Earl C. Michener, a Republican from Michigan, introduced House Joint Resolution 27, barring a third presidential term and limiting a vice president serving more than a year of a predecessor’s unexpired term from seeking more than one term of his own. Michener, by the way, was starting his 14th term in Congress.

Republicans added a clause exempting incumbent Harry S. Truman, a bipartisan touch Democrats saw as window dressing. Backers said they were giving voice to American fears of authority residing in one person for too long.

Here was a chance for Congress to oppose the “tendency toward dictatorial government” and return to government “based upon law and not upon men,” said Rep. James I. Dolliver, Republican from Iowa.

“Power corrupts even when it is in the hands of angels,” said Sen. Alexander Wiley, a Wisconsin Republican.

Nay Sayers

Critics said the GOP distrusted the electorate.

“Turn and twist it as you will, the proposed amendment is a vote of no confidence in democracy,” historian Henry Steele Commager wrote.

Why rely on voters to choose a president for a first and a second term but not a third? asked Sen. Joseph L. Hill, an Alabama Democrat

“It is a well-known fact, thank God, that dictators are not bred or conceived in free and open elections such are held in the United States of America,” said Rep. Frank Chelf, Democrat from Kentucky.

Rep. Adolph J. Sabath, an Illinois Democrat, accused the GOP of seeking “a pitiful victory over a great man now sleeping on the banks of the Hudson.”

Nonsense, said Michener, the Michigander who’d introduced the bill to the House: “It’s not a matter of personalities. We favor a limitation of eight years … on any President, whether he be a Democrat or a Republican.”

No Take Backs

Under the amendment, a president would not be able not seek a third term no matter what.

“Sometime in the future, if our country is engaged in a war and our back is to the wall, and a future generation has a President whose second term is drawing to an end, this very amendment could … place future generations of Americans in a straitjacket and seriously imperil the continued existence of our country,” said Rep. John McCormack, Democrat from Massachusetts.

No president is indispensable, advocates retorted.

“The people recognize that there are many — yes, many — who are able to assume the work of any person, in any position, at any time,” said Rep. Raymond S. Springer, Republican from Indiana.

The Taft Hypothetical

On Feb. 6, 1947, the House approved the resolution 285-121, including yea votes by Rep. John F. Kennedy (Democract from Massachusetts) and Rep. Richard M. Nixon (Republican from California).

On March 12, Sen. Robert A. Taft (an Ohio Republican) offered an amendment to the House resolution. Taft left intact the two-term limit but extended to two years the portion of an unexpired term an elevated vice president could serve before being limited to only one term of his own.

Had those limits applied in 1912, Taft’s father probably would have been president twice. That year, Theodore Roosevelt ran on a third-party ticket. He split the Republican vote with William Howard Taft, tilting the presidency to Woodrow Wilson. The younger Taft’s limits would have barred a Roosevelt run because, before winning the White House in 1904, he had served three years of William McKinley’s term.)

Tables Turned

The Senate and House approved the Taft resolution. The amendment went to the states for ratification, with a deadline of March 21, 1954. During 1947, 18 states ratified. By 1950, six more had done so. The Republican National Committee put on a full-court press, and on Feb. 27, 1951, Minnesota became the 36th state to ratify. The 22nd Amendment took effect.

Truman retired in 1952. Former Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, running as a Republican, won a towering presidential victory over Democrat Adlai Stevenson. In 1955, a serious heart attack landed Eisenhower in the hospital, with Vice President Richard Nixon informally standing in for him until he recovered. Eisenhower’s landslide re-election a year later — he again beat Stevenson, this time by 9 million votes — led to talk of repealing the term limit.

Ike had vacillated on the 22nd Amendment, at first opposing the measure, feeling voters should be allowed to elect whomever they want as president. But he came to believe “on balance, it was good for the nation.”

“Look, I will give you people a piece of news,” Eisenhower told reporters in 1957. “They can repeal it if they want to. I shall not run again.”

Ike at All Costs

Still, Ike’s boosters wouldn’t give up on the idea of an Eisenhower threepeat.

Despite Eisenhower’s popularity, he had short coattails. In 1956, amid his landslide, the GOP lost two Senate seats and two House seats; in 1958, even with Eisenhower’s approval at 60%, the GOP lost 13 Senate seats and 48 House seats. In 1960, whoever headed the GOP ticket — Nixon was chasing the nod with ardor — was obviously unlikely to repeat Eisenhower’s overwhelming success with voters.

Rep. Clare E. Hoffman, a Michigan Republican, suggested Ike run as a Democrat because, Hoffman said, a “complaisant” U.S. Supreme Court might read the 22nd Amendment to bar three terms only to presidents running under the same party’s aegis. Or the genial golfer and father figure might accept a lesser but still potent spot. At a press conference on Jan. 13, 1960, Eisenhower joked about a vice presidential run — a jest his party took seriously enough to seek an opinion from Attorney General William P. Rogers, who said it would be permissible — a curious call, since the 12th Amendment provides that “no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.”.

Shoe, Meet Other Foot

Nevertheless, bowing to the 22nd Amendment, Ike, 70, retired. Nixon narrowly lost a nail-biter to Kennedy. According to Time, Eisenhower “could obviously have licked Kennedy and any other two Democratic candidates combined.” Capital insiders, wrote New York Times columnist James Reston, believed Eisenhower could have won easily had not the Republicans of 1947, “in a spasm of retroactive vindictiveness,” engineered the 22nd Amendment. Truman and fellow Democrats enjoyed seeing the awareness dawn on Republicans, as the former president put it, that they had “cut their own throats with that amendment.”

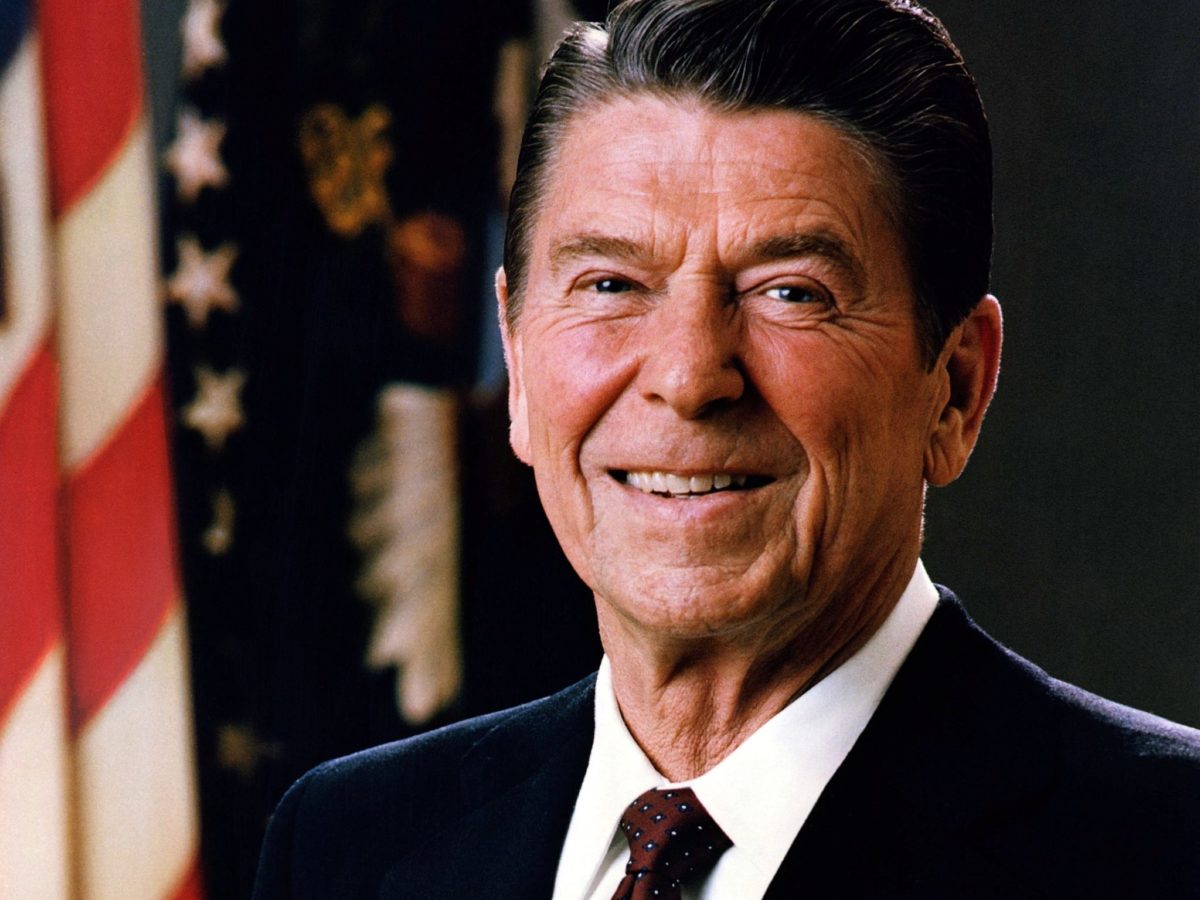

America’s next president to serve two terms, Republican Ronald Reagan, favored repealing the 22nd Amendment.

“The people ought to have a right to decide who their leadership would be,” Reagan said in 1985 after riding a landslide to reelection.

But even if the amendment were repealed during his second term, Reagan said, he would not run again despite approval ratings high enough to make a third term a realistic possibility.

Nevertheless, Rep. Guy Vander Jagt, a Michigan Republican, sent more than 1.3 million Republicans a petition and request for donations, arguing that voters “can’t think of an America without Ronald Reagan.”

His repeal resolution never got out of committee. Time wrote off the Michigander’s threefer gambit as “a gimmick designed to fatten G.O.P. coffers.”

Since then, the two-term limit has stood fast. Of five presidents barred from seeking a third term, the two likeliest to have done so with success were pillars of the party that made this impossible — a lesson about constitutional amendments and unintended consequences that extends into related realms. Some Democrats, angry that Hillary Clinton decisively won the 2016 popular vote but lost in the electoral college, agitated to eliminate the electoral college altogether and make the popular vote dispositive. House and Senate partisans introduced joint resolutions to accomplish that — by amending the Constitution.

In response, then-Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, a Nevada Democrat, with characteristic understatement, called for circumspection.

“No one knows what is going to happen four years from now, eight years from now, 12 years from now,” Reid, who died in 2021, said.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.