In January 1940, president Franklin D. Roosevelt is one year from completing his second term in office. While there is no constitutional prohibition against seeking a third term—and will not be until the 22nd Amendment is ratified in 1951—no previous president has defied the precedent established by George Washington in 1796 that two terms is enough. One prominent Republican growls that for a president to hold office for 12 years would be a long step toward totalitarianism.

But FDR doesn’t appear to be headed in that direction. On New Year’s Day, the Chicago Tribune reports that if FDR seeks a third term it will divide the Democratic Party, set the stage for a floor fight at the Democratic National Convention when it meets in July, and open the door to a Republican victory in the general election that November. For these reasons, the paper says that FDR “has abandoned any notion of seeking a third term and will back Secretary of State Cordell Hull for the nomination.”

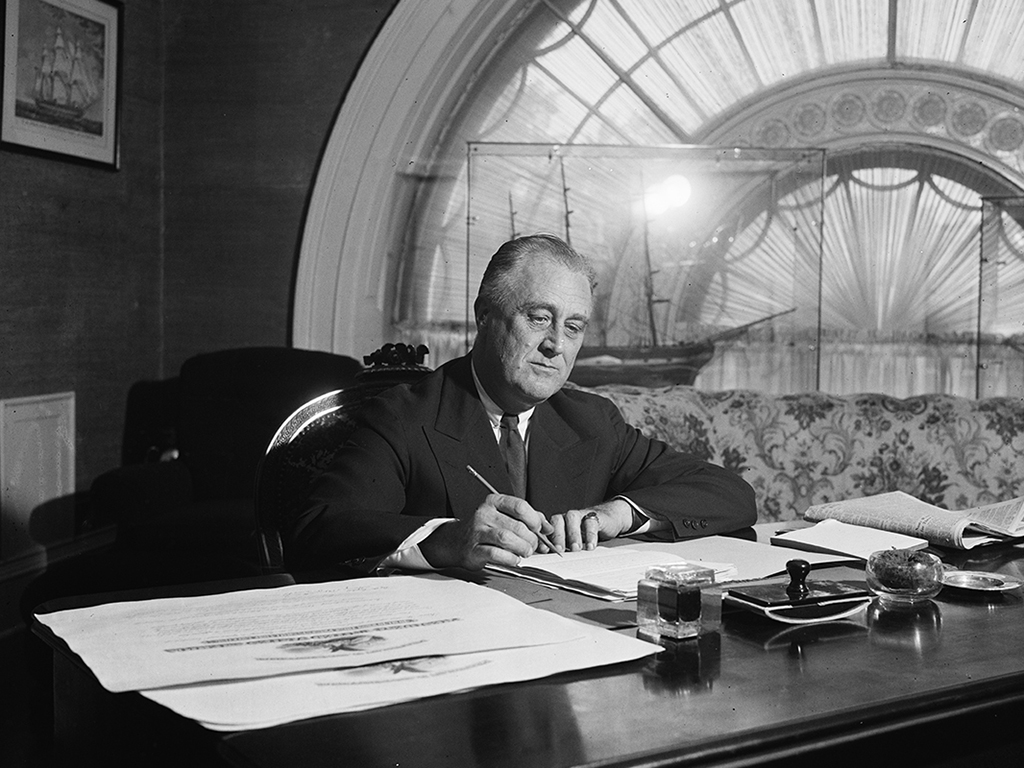

FDR’s private actions and conversations support that report. On January 20 he signs a three-year contract with Collier’s magazine to write 26 articles for a commission of $1.2 million per year (at present-day values). Four days later he tells a cabinet member, “I do not want to run unless between now and the convention things get very, very much worse in Europe.” He speaks with enthusiasm about the imminent removal of his public papers to a new presidential library in Hyde Park, New York. And in February he complains of being chained to the presidential chair “from morning till night…. And I can’t stand it any longer.”

Of course, FDR is a famously canny, sometimes devious politician. It cannot be ruled out that secretly he hopes for a third term. Observers note that he does little to groom a successor for the presidency. His refusal to firmly declare that he will or will not be a candidate makes it impossible for other Democratic aspirants to campaign openly for the nomination. In any event, the shocking defeat of France in June 1940 assuredly means that things in Europe have gotten “very, very much worse.” FDR announces that while he will not campaign for the nomination, if he is drafted to run at the convention, he will do so.

The gambit backfires. Jim Farley, the chair of the Democratic National Committee, visits FDR at the president’s private home in Hyde Park to urge him against even a tacit run for a third term. When this fails, Farley allows supporters to place his own name in nomination. Newspaper editorials across the country blast FDR as disingenuous. Despite initial support from numerous state delegations, the “Draft FDR” movement collapses. But so does the convention, for the delegates cannot agree upon a candidate to rally behind. After numerous ballots it settles, in a spirit of exhaustion rather than enthusiasm, upon the candidate to whom FDR has given his support: 69-year-old Cordell Hull.

The ensuing campaign is a disaster for the Democrats and an unexpected triumph for the Republicans. Hull shows scant aptitude for the campaign trail. The GOP, on the other hand, has nominated an unlikely but charismatic 48-year-old candidate, Wendell Willkie. The president of a major utilities holding company, Willkie has never run for public office. But he has extensive experience in politics and proves an adept and vigorous candidate. Crisscrossing the country in a 16-car train dubbed the “Willkie Special,” he racks up 18,789 miles through 31 states, stopping to make 560 speeches.

A Democrat until January 1940, Willkie is what will one day be described as a “modern Republican.” He accepts most aspects of the New Deal and is critical mainly of the way FDR has administered its programs. A liberal on civil rights, he does much to bring the black vote back to “the party of Lincoln.” He does surprisingly well in courting the labor vote and gains the endorsement of several prominent labor organizers. And unlike many Republicans, Willkie is an internationalist, meaning that he rejects isolationist policies and favors a foreign policy that supports the foes of Nazi, Fascist, and Japanese aggression. In November, he soundly defeats Cordell Hull.

The above scenario is historically accurate in every detail, save that the “Draft FDR” gambit worked and Roosevelt defeated Willkie for the presidency in 1940. Roosevelt’s reluctance to run for a third term is a matter of record, as is Farley’s strident opposition to such a run and the misgivings of several prominent newspapers about the propriety of his doing so. The story of Willkie’s astonishing campaign is also factually correct. Willkie lost to FDR by 5 million votes, amassing more votes than any Republican nominee between 1928 and 1952.

But what if Willkie had become president in 1940? His subsequent career pro vides numerous clues as to the policies he would have pursued. During the 1940 campaign, Willkie supported FDR’s decision to give 50 World War I destroyers to Great Britain in exchange for basing rights in the Caribbean. He also supported passage of the 1940 Selective Service Act, the first peacetime draft in American history, as well as the Lend-Lease Act. In February 1941 he made a goodwill trip to Great Britain that underscored America’s commitment to that embattled nation. A round-the-world tour followed the next year and, in 1943, he published an inter nationalist manifesto that criticized European colonialism, looked to China as a rising power, and favored the creation of international institutions similar to the eventual United Nations. All this indicates that as president, Willkie would have pursued policies similar to Roosevelt’s.

The record suggests that he might have differed with FDR in only two important respects. Although he refrained from direct criticism of the Japanese American relocation program, his public remarks imply that he regarded it as unnecessary and unjust. And during a visit to Moscow in 1942, he went on record as favoring “a real second front in western Europe at the earliest possible moment our military leaders will approve.” Since American military planners strongly favored an early cross-Channel attack, it is possible that President Willkie would have eschewed Operation Torch—the invasion of west ern North Africa—in favor of Operation Roundup, the American plan for a 1943 cross-Channel attack. Had he done so— and had the Americans succeeded in persuading their reluctant British allies—it is likely that the attempt would have achieved at best a limited foothold on the Continent. It might even have failed altogether, and possibly prolonged the war.

Two other important issues remain, of necessity, imponderable. Could Willkie, as a first-term president without previous experience in public office, have been as effective a commander in chief as Franklin D. Roosevelt? Probably not. But as an inexperienced though intelligent first-term president, he would likely have accepted the counsel of the highly competent American senior command even more readily than did FDR. Second, Willkie died of a massive heart attack in October 1944. Given the stresses of the office, one must assume that he would have met the same fate had he been elected president. And since his running mate, Sen. Charles McNary of Oregon, died even sooner—in February 1944—Willkie would have had to nominate someone to replace McNary as vice president. That raises an even greater unknown: Who then would have been president in 1945, faced with the awesome decision to use the atomic bomb?

Originally published in the September 2009 issue of World War II. To subscribe, click here.