On the morning of Oct. 25, 1813, the inhabitants of Nuku Hiva—the largest of 15 islands comprising Polynesia’s remote Marquesas—awoke to the startling sight of a six-ship flotilla approaching from the east across the cobalt-blue South Pacific. While the islanders were accustomed to occasional visits by whaling vessels seeking fresh water or shelter from storms, never had so many masts appeared over the horizon at one time.

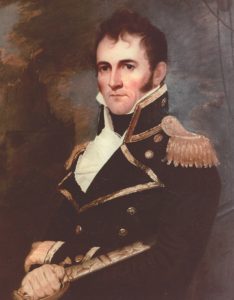

Though five of the new arrivals appeared nonthreatening, the lead ship was anything but. Significantly larger than its companions, it boasted three tall masts and a row of gunports along either side of a hull painted black as death. Even to the islanders’ untrained eyes the vessel was obviously a warship. The vessel was in fact the frigate USS Essex, but despite the ship’s menacing appearance its captain, 33-year-old David Porter, had not brought his small fleet to remote Nuku Hiva looking for a fight. He simply needed a place to hide.

Following the outbreak of war between the United States and Britain in June 1812 Essex had captured nearly a dozen British vessels off Bermuda and in the Caribbean. In February 1813, after a return to New York and subsequent voyage down the Atlantic coast of South America, Porter rounded Cape Horn into the Pacific. His intent was to find and either capture or destroy ships of Britain’s wide-ranging whaling fleet, hoping to put a significant dent in the enemy’s economy. Over the next eight months Porter and his crew captured a dozen more enemy vessels and took 360 prisoners, a success that prompted the Royal Navy to send two warships—the 53-gun frigate Phoebe and 28-gun sloop Cherub—after Essex and its attendant flotilla.

But evading British warships was not Porter’s only reason for shaping a course for the Marquesas. After 11 months at sea Essex was in desperate need of an overhaul. Porter needed somewhere to beach the frigate so his crew could scrape its bottom, repaint its hull and effect other repairs. And then there were the rats. They had eaten their way into every corner of the ship, gnawing at water casks and chewing on sail canvas. They had even penetrated the ship’s magazine and eaten cartridges. To smoke the vermin out, Essex first had to be emptied.

The Marquesas seemed the perfect place for Porter and his small fleet to lay low while overhauling Essex. Though first visited by Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira in 1595, then again in 1774 by famed British explorer James Cook, the islands’ remoteness ensured they remained off the beaten track for most Pacific voyagers. Nuku Hiva, the largest of the group, offered fresh water, firewood and long stretches of sandy beaches along sheltering bays—perfect for careening Essex. Though the Marquesans were rumored to be cannibals, Porter believed Essex’s 46 guns and complement of 66 officers, 227 sailors and 25 Marines—and, if necessary, the British prisoners and few cannons aboard the captured whalers—could keep things under control. He was mistaken.

Soon after Essex dropped anchor in sheltered Taiohae Bay on Nuku Hiva’s south coast, Porter noticed three deeply tanned, heavily bearded white men shoving off from the beach in a small boat. As they came alongside and hailed Essex, Porter instinctively waved them off, believing them to be deserters. He soon regretted his haste, however, for as the trio regained the beach, a group of armed warriors massed around them. In order to accomplish Essex’s refurbishment, Porter would need to be on good terms with the islanders, and the white men might be able to help him establish the cooperation he needed. He resolved to correct his error.

Ordering four whaleboats loaded with Marines and armed sailors, the captain led the party ashore, the warriors vanishing on their approach. On reaching the beach, Porter stepped cautiously from his boat, alert for any sign of ambush. Moments later from the brush emerged two of the three white men—one clad in tattered trousers and a faded shirt, the other heavily tattooed and wearing only a loincloth. As Porter’s men disembarked, Lt. Stephen Decatur McKnight was shocked to recognize the clothed man as a former shipmate, Midshipman John Maury. Maury explained that he and four others had disembarked from an American merchant vessel two years earlier to gather a cargo of sandalwood while their captain sailed on to trade for supplies in China, but the ship never returned. (Unknown to them, it had run up against a British blockade.) Maury’s tattooed companion introduced himself only as Wilson, an English sailor who had been on the island some years and had learned to speak the local language. Neither knew about the present war.

Wilson told Porter the lush valley behind them was the home of the Tei‘e tribe. As the pair spoke, a group of warriors bearing 14-foot black toa wood thrusting spears and highly decorated war clubs formed a semicircle around the Americans as other islanders gathered nearby. Wilson explained that each valley on the island was overseen by its own tribe, and that he had been with the Tayees, as he called them, since arriving on Nuku Hiva. The Englishman also warned the captain the tribes were in perpetual war with one another.

As Wilson spoke, Porter looked over the Marquesans. He found them an attractive people—tattoo-covered men tall with chiseled features, and scantily clad women that would turn heads in Boston. The latter had drawn the rapt attention of the sailors in Porter’s landing party, though the Tayee men did not seem bothered by the open flirtation.

To impress the growing crowd, Porter had his Marines go through close-order drill, marching back and forth to the drum and firing volleys from their musket. The captain then asked Wilson for an introduction to the Tayee chief. Chief Gattanewa, the Englishman explained, was in a fortified village at the head of the valley. After dispatching a messenger with an invitation to meet the chief, Porter distributed small gifts (knives, fishhooks, etc.) to the Tayees.

The formalities over, Porter turned to board the whaleboats and row back to Essex. To his surprise, he discovered that all members of the landing party, aside from the unhappy Marines, had vanished into the bush with the women. Porter himself was proffered a dalliance with Gattanewa’s 18-year-old granddaughter but thought better of it. Allowing his men their hurried liaisons with the Marquesan women, he eventually managed to herd the sated sailors back to the whaleboats and return to the ship. “If an allowance can be made for a departure from prudential measures,” the captain later reflected in his journal, “it is when a handsome and sprightly girl of 16, whose almost every charm is exposed to view, invites to follow her.” Porter soon found it necessary to allow a further “departure from prudential measures.”

As the landing party reboarded the ship, the Tayee women lined the beach, waving coyly to the crewmen aboard Essex and the five captured whalers anchored around it. Those who’d gone ashore soon told their shipmates about the very warm welcome they’d received, and those who’d stayed aboard soon lined the rails, anxious to experience similar degrees of hospitality. Wary of allowing the men shore leave till he’d met with Gattanewa, Porter also appreciated the potential blowback if he didn’t allow his men access to the women. Thus once the ship was securely moored, he again dispatched the whaleboats to the beach. They returned filled with women, who eagerly paired off with the men. Petty officers with keys to storerooms found some privacy, while topmen led their new friends aloft to the masthead platforms.

Porter retired to his cabin alone, though he could hear raucous laughter and other noises through the thin bulkheads. He reasoned the exchange was only natural, given his men had endured enforced celibacy for long months since their last shore leave in Chile. Maury and Wilson had explained that Marquesans considered nudity and sex a part of everyday life. “If there was any crime, the offense was ours, not theirs,” Porter wrote. “They acted in compliance with the customs of their ancestors.”

After their initial orgy, the men seemed to settle down. Porter proudly noted in his journal that each man confined himself to one steady female partner. Everyone, that is, save for his 12-year-old stepson, Midshipman (and future U.S. Navy admiral) David Farragut, and two others not yet 15. They were confined to the ships.

Once the helmsman had beached Essex, the crew began emptying the vessel, at the same time setting up camp ashore. Once the frigate had been stripped of everything but her cannons, the crew set firepots throughout the ship, ignited them and closed all hatches. The resultant smoke killed some 1,500 rats, whose bodies crewmen tossed into the bay. Porter then hired Tayees to help scrape the hull using shells and coconuts. He’d discovered the Marquesans would accept prized whales’ teeth as currency and used them to pay for the hull-cleaning services and for fresh fruit and hogs.

Barely a week after the Tayee set to work, a brief skirmish interrupted the project, when several hundred warriors from the neighboring and decidedly hostile Hapa‘a tribe descended into the valley and threatened the camp. Cannon fire and sallies by the Marines and armed sailors soon chased them off. When Porter sent a messenger suggesting the two sides come to terms, the Hapa‘as rebuffed him, decried the Americans as cowards and said their warriors would return to carry off all their supplies.

Porter dared not lose face before the Tayees, so he sent Navy Lt. John Downes and Marine Lt. John Gamble with 40 Marines and armed sailors against the Hapa‘as’ mountain stronghold. Accompanied by Tayee war chief Mouina and several dozen of his men, the party made the ascent with a 6-pounder cannon in tow. They found the Hapa‘a fort occupied by upward of 3,000 warriors eager for a fight. As the Americans sized up the situation, Gamble took a stone to the belly that knocked the wind out of him, while a nearby sailor suffered a glancing wound from a thrown spear. Downes responded by using the 6-pounder to blow open the gate to the fort, allowing the Americans and their Tayee allies to rush in. The attackers killed five enemy warriors outright and wounded many more, prompting the defenders to break and run. Several of the raiders sustained wounds, but none were killed, and all returned safely to camp with much plunder.

In the wake of their defeat the Hapa‘as asked for terms, and Porter negotiated a weekly tribute of hogs and fruit. Hearing of the clash, other tribes sent representatives to meet with the captain. They, too, agreed to provide the Americans and their captured British whalers with food as the men worked on the ships of the improvised fleet.

The Marquesan workers also helped build a small village for the Americans, all of it constructed in a day. Feeling somewhat self-assured, Porter decided to rename the island Madison’s Island, after the sitting U.S. president, and he dubbed the village Madison’s Ville. The bay where Essex and the whalers swayed at anchor he named Massachusetts Bay. He then had a small fort built and armed it with four cannons. During a flag-raising ceremony and 17-gun salute on November 19, Porter declared the annexation of the Marquesas by the United States and pledged to extend protection to all tribes that swore allegiance to the flag. Finally, he had the annexation document sealed in a bottle and buried in a marked spot at the foot of the flagstaff, there to warn off any European voyagers who might have designs on the islands.

The relative calm that prevailed on Nuku Hiva following his defeat of the Hapa‘a did not last as long as Porter had hoped. Within weeks the food contributions from the island’s tribes stopped. When Porter questioned Gattanewa, the elderly chief explained that the largest tribe on Nuku Hiva, the Typee—which had not sworn its allegiance—had been calling the other tribes “dogs” for obeying the Americans, whom they dismissed as “white lizards, mere dirt.” Those tribes were openly wondering why Porter did not make war against the Typee. Were the Americans too weak—or perhaps too frightened?

Cognizant that any perception of weakness on his part could well endanger his men and ships, Porter decided to act preemptively and planned one of the first American amphibious landings in the Pacific. Using a captured whaling sloop he’d renamed Essex Junior and equipped with 20 short-range guns, he boarded three dozen Marines and armed sailors and set sail for the Typee side of the island. Joining the expedition were roughly 200 war canoes supplied by the Tayee and allied tribes. The war party numbered some 5,000 men. Porter would command the attack on the Typee stronghold.

All was quiet when the landing party came ashore. But as Porter’s column hacked through the jungle toward the Typee fort, enemy warriors ambushed it from cover. “We could hear the snapping of the slings, the whistling of the stones,” Porter recalled. “The spears came quivering by us, but we could not perceive from whom they came.” Though their Marquesan allies started to melt away, Porter’s men marched on, dispersing the Typees with a scattering fire.

On fording a stream, the party encountered a 7-foot-high wall flanked by impenetrable thickets against which their muskets were useless. By then Porter’s party had been reduced to 19 effectives, and only Mouina remained of the Marquesans. Worse yet, the men were down to just a few cartridges each. Having presumed a quick and easy victory, Porter had not brought enough ammunition for a prolonged attack. With his Marines acting as a rear guard, Porter ordered a retreat to the boats. At a cost of four men wounded, the Americans had killed two Typees and wounded countless others. But they’d suffered a humiliating loss.

On his return to Madison’s Ville, Porter discovered popular opinion had turned against the Americans. He had to defeat the Typees or face the possibility his own allies might wipe out his small force. “Our only hope of safety was in convincing them of our superiority,” the captain noted in his journal.

The next morning Porter called for a conference with Mouina. When asked whether a force could enter the Typee valley from the island’s high ground, the war chief said his warriors could, though he wasn’t sure the Americans could manage the strenuous ascent. Furthermore, Mouina explained, if such an attack failed, the strike force would be trapped, and the Typee would have their bones. Porter decided to roll the dice and lead the attack.

As the 200-man American force made the climb that moonlit night into the interior, Mouina’s warriors served as guides and porters. On reaching the summit, Porter’s exhausted men made camp. They woke to rain that persisted through the morning and were forced to spend the rest of the day in the stronghold of the Hapa‘as as they waited for their gunpowder to dry. Finally, on the morning of the third day, November 30, the Americans reached an overlook of the Typee valley, lush with breadfruit trees and dotted with villages fortified with walls. The valley was 3 miles wide and stretched 9 miles down to the sea.

As the Americans and Tayees picked their way down the volcanic cliffs, Typee warriors outside the first fortified village spotted the raiders and dared them to descend. Porter had his Marine sharpshooters scale coconut trees to snipe at defenders while the bulk of his force charged. They were met with spears. On cue the Americans stepped back and fired into the enemy spearmen, dropping several. The Typees stubbornly held their position, losing some two dozen warriors, until the death of their chief. With the enemy in flight before them, Porter’s men had just entered the village when a group of warriors made a suicide charge, breaking the American line before being slaughtered. Porter had the village razed. The captain then sent a captive Typee with a message to those waiting below, advising surrender lest the Americans destroy their remaining villages. No reply came.

After setting up a hospital for his wounded, Porter resumed his advance down the valley. Each village put up a brief fight, and the Americans burned nearly a dozen more. As the raiders made for the beach, the Typees fled into the hills, and resistance evaporated. On reaching the shore, Porter was greeted by grateful emissaries from the Hapa‘as, who coaxed him and his men to return to their mountaintop stronghold and celebrate their great victory into the night. The next morning the Americans, weary and wounded but alive, marched into Madison’s Ville. A day later emissaries from the Typees arrived, suing for peace. Porter had conquered Nuku Hiva.

By December 9 Essex and the rest of the makeshift fleet were ready to sail. Porter was aware the two British warships were scouring the Pacific for him. Despite his dearth of long-range cannons (just six 12 pounders), the emboldened captain decided to go looking for them. To reinstill discipline, he canceled all shore leave. The Marquesan women responded by lining the shore, wailing and cutting themselves with shell shards. When the Marine guard captured three sailors slinking away to meet their lovers, Porter had them flogged. Another sailor managed to slip ashore unnoticed.

As morale plummeted aboard Essex Junior, British-born sailor Robert White tried to stir up a mutiny. Porter responded by assembling the crew on deck and reminding them of the penalty for mutiny. Drawing his sword, he then called out a trembling White. “An Indian canoe was paddling by the ship,” the captain recalled. “I directed the villain to get into her and never let me see his face again.”

The rest of the men grumbled but remained loyal. Porter’s plan called for Essex and Essex Junior to sail for Chile to pick up supplies and determine the whereabouts of the British warships. Meanwhile, the prize ship New Zealander, loaded with whale oil from the other captured vessels, would make for the United States, then under British blockade. The three other whalers—Sir Andrew Hammond, Seringapatam and Greenwich—would remain at Madison’s Ville along with two midshipmen, 19 sailors (including several British-born sailors) and six prisoners. Gamble would be in command in Porter’s absence.

On December 13 Essex and Essex Junior weighed anchor. A month later Porter sailed into port at Valparaiso, Chile. The British soon got wind of his whereabouts, and Phoebe and Cherub arrived offshore two weeks later. On learning the American warships had only short-range cannon, the British warships set up a blockade. After several feints and false starts, Porter made a run for the open sea on March 28. In the naval engagement that followed, the British simply kept their distance and shot their opponents to pieces. After losing 154 men killed, wounded or missing, the American commander surrendered his ships. Essex served the Royal Navy in various capacities into the 1830s. After disarming Essex Junior, the British loaded Porter, stepson Farragut and the other prisoners aboard and transported them stateside under parole. On arrival the ship was condemned and sold.

Back in the Marquesas, Gamble proved an ineffective governor. Lacking both the presence and tact of Porter, the lieutenant little resembled a leader in the eyes of the Marquesans. As Gamble commanded only a token force, tribesmen began ignoring his orders and requests.

On May 7 the British-born sailors among the garrison Porter had left behind mutinied, freeing the six prisoners before attacking the small fort overlooking the harbor. The mutineers then sailed off on Seringapatam, setting the lieutenant and four others adrift in a small boat, though not before one of them carelessly shot Gamble in the foot. As the whaler vanished over the horizon, Gamble and the others managed to row back to Nuku Hiva.

The Tayee had seen everything. All the while Wilson was stirring them up, insisting Porter would never return. Two days later Tayee warriors attacked six of the Americans ashore, killing four; the other two managed to escape. Gamble was alone aboard Sir Andrew Hammond, still recovering from his wound, when two war canoes paddled out from the beach. The ship’s cannons were already loaded, so Gamble hobbled from gun to gun, touching them off. The war canoes turned back.

The next morning Gamble ordered Greenwich burned and Madison’s Ville evacuated. Only eight Americans remained alive, five of whom were wounded or ill. Once they were aboard Sir Andrew Hammond, the lieutenant set a course for Hawaii. In late May, having sailed nearly 2,500 miles, the American-flagged whaler anchored off Oahu. After augmenting his crew, Gamble set out for Hawaii on June 11, but this time luck was not with him. A day out of port the ship ran afoul of Cherub, which seized the whaler and captured its American crew. Gamble didn’t make it home until August 1815. The war had ended six months earlier.

On returning stateside, Porter—who was rewarded with a small fortune in prize money—sought vindication of his actions through a court of inquiry, as well as congressional ratification of his annexation of the Marquesas. When the continuing war suspended an inquiry, Porter published his journal. That in turn likely ended all hopes of annexation, as official Washington was mortified to read of the licentious behavior U.S. naval personnel had exhibited during their sojourn on Nuku Hiva.

In 1842 a fleet of French warships annexed the Marquesas. Ashore to witness their arrival was Herman Melville, who had jumped ship from an American whaler and later wrote of his experiences in the 1846 travelogue Typee. In the 1880s colonial authorities incorporated the islands into French Polynesia. Whether they ever unearthed the bottle containing Porter’s annexation document is unknown. MH

Mike Coppock writes from Enid, Oklahoma. For further reading he recommends The Savage Wars of Peace, by Max Boot; The Odyssey of the Essex, by Frank R. Donovan; and Nothing Too Daring: A Biography of Commodore David Porter, 1780–1843, by David F. Long.

This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: