Piedmont, Wyo., is known less as a ghost town and more as a state historic site centered on a trio of large beehive-shaped charcoal kilns. The town, such as it is, lies a half mile to the southwest, partly on private cattle range. Accessible by two-wheel drive on the firm dirt County Road 173 (aka Piedmont Road), scarcely 7 miles south of Exit 24 off I-80, Piedmont offers ghost town aficionados the well-preserved kilns, a half dozen derelict structures and slices of Mormon, transcontinental railroad and charcoal-making history.

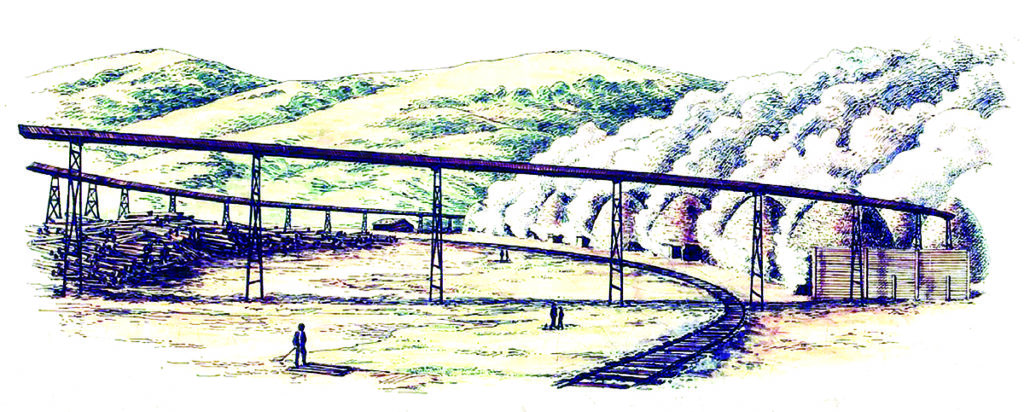

Around 1867 English-born Mormon emigrant Moses Byrne—a polygamist, father of nearly two dozen children and serial entrepreneur—established a water- and wood-refueling station here in anticipation of the approaching Union Pacific. The proud pioneer first dubbed the town Byrne, but confusion with the existing trackside town of Bryan, farther east, required the name change to Piedmont, the home region of his two Italian wives. Soon after railroad crews laid track through in late 1868, Byrne built six kilns—one to produce lime for mortar, five to supply charcoal to iron smelters farther west in Salt Lake City and the blacksmith back up the line in Fort Bridger. Piedmont soon turned into a growing concern. Besides the Union Pacific depot, roundhouse and water tank, it boasted a telegraph office, post office, general store, schoolhouse, three-story hotel, newspaper, the requisite saloons, a smattering of homes and several family cemeteries.

Wood was scarce along much of the Union Pacific line through Wyoming Territory, which had formed on July 25, 1868. But south of Piedmont, just across the Utah state line, stretch the Uinta Mountains. Thus within 20 miles of town was a reliable source of timber to render into charcoal and supply lumber for construction and railroad ties.

Byrne was not alone in recognizing the need. Fourteen miles west of town lay the company town of Hilliard, which boasted some 30 charcoal kilns, a sawmill and a 30-mile-long flume down which to float timber down from the Uintas. Farther west still was Evanston, home to two charcoal companies and a dozen more kilns, whose lumbermen sent logs down the Bear River from the Uintas each spring. Only the Piedmont kilns remain intact and readily accessible.

By 1896 the Salt Lake Daily Tribune was reflecting on the town’s waning fortunes:

Piedmont, Wyo., in the early days of the Union Pacific was a lively little town where stores, saloons and gambling rooms thrived and money was plentiful with the denizens and its hundreds of woodchoppers, lumber and timber men and scores of coal burners. Today there remain but a few of the log houses, while the big beehive-shaped charcoal kilns are all that remain to point to the past flush times of the town. When charcoal gave way to coke in the smelting furnaces, wood became a thing of the past for use in locomotives and the lumber market had its bottom knocked out by importations from Oregon, Washington and California, there was nothing left in business in these lines, and citizens turned their attention to railroad ties and mine props.

What finally sounded the death knell for Piedmont was the Union Pacific’s decision to reroute its tracks farther to the north in 1901, bypassing town. The last store closed in 1940.

Among other interesting historical connections, Piedmont factored into the May 10, 1869, golden spike ceremony, when the Central Pacific and Union Pacific linked up at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, to complete the transcontinental railroad. Originally scheduled for May 7, the ceremony was delayed when Union Pacific road crews seeking back pay blocked the train carrying company dignitaries at Piedmont. It proceeded to Utah only after Union Pacific Vice President Thomas Durant wired for the money and paid off the irate crews. Rumor has it infamous outlaw Butch Cassidy frequented the area and reportedly buried the loot from one of his bank robberies near Piedmont. Treasure hunters still seek it. Calamity Jane also spent time in Piedmont as a teen orphan, taking whatever jobs she could to support her five younger siblings. Soldiers from Fort Bridger partied in town, and Jane soon became a notorious camp follower.

What proves most interesting to modern-day visitors are the charcoal kilns. Built of native sandstone stacked and layered with lime-sand mortar, each stands 30 feet high and 30 feet in diameter with walls some 2 feet thick. Facing east at ground level, away from the road, are 6-by-5-foot arched doors through which to load firewood and unload charcoal. Facing west near the peak of each kiln, visible from the road, are other small openings through which to load wood. Ventilation was provided by offset rows of intake holes around the bottom few feet.

Just how did the kilns work? Charcoal is the black carbon residue of wood burned under high temperatures in limited oxygen. Once each kiln had been loaded to the top with wood and fully fired, the loading doors were sealed off to create that nearly airless environment. A local newspaper described the process:

Each [kiln] held 35 cords, 4-foot length, all the local woods—lodgepole pine, aspen and spruce—being used. The ovens were filled from a door at the base and one near the apex, fired from the former and then both doors sealed shut. A series of vent holes around the base furnished the only air and thus drew downward the fire, which first shot to the top of the kiln. As flames appeared at each of the vent holes, it was closed with a brick until it was smothered. After a week the kiln had cooled and was emptied and recharged.

The three intact kilns, the remains of a fourth, a nearby cemetery and a handful of tumbledown homes off the right side of the road draw mainly those interested in ghost towns and our railroad past. It is well worth the detour to hear the wind whispering history through the ruins.