Not all the tracklayers were Irish or strictly meat-and-potatoes men.

First of all, they were all Irish. Second, they had to fight Indians every step of the way while laying track. Third, they ate and drank themselves to death on meat and potatoes and rotgut whisky instead of eating vegetables and seafood like the Chinese. Fourth, they spent the last of their money in whorehouses. Fifth, they blew rival Chinese to pieces with blasting powder out of envy. Sixth, they built the Union Pacific half of the first transcontinental railroad, arguably the single most significant construction project in American history.

Only the last statement above is strictly true. The legend—actually the myth—of the Union Pacific grew with the telling, and many of the stories featured in popular accounts and Hollywood movies were not genuine frontier events.

The work itself was impressive enough to be legendary. Major General Grenville Dodge of the Union Pacific, commanding an “army” of 10,000 men and 10,000 draft animals, sent out advance parties to survey the route. Each party comprised a chief engineer, an assistant engineer, rodmen, flagmen, chainmen, axmen, teamsters and hunters. Location men came next to mark the exact grade with flags, and the graders, first and perhaps heaviest of laborers, followed to even out the route with blasting powder, picks and shovels. Bridge men, specialists in heavy-duty carpentry, worked as much as 25 miles ahead of the tracklayers, building bridges that were sometimes shaky but always ready in time to let the tracklayers work without breaking stride. The advance crew was supplied by pack mule or wagon and fed from a herd of 500 cattle—because, contrary to the legend of Buffalo Bill Cody, few railroad men would touch buffalo meat under any circumstances.

The redoubtable tracklayers trailed the advance work at a relentless pace. Little flatcars—each pulled by a single husky horse usually led by a runaway or an orphan not strong enough to help hoist the iron—would transport the rails and the ties, or “sleepers.” There were five ties to a 28-foot length of rail. The tracklayers would lay out the sleepers, and 10 men, five on a side, would lift the 500- to 700-pound rails (contractors sometimes cut corners on the amount of iron used) and lay them down with a practiced eye virtually in grade.

The term “gandy dancers” may have come from the odd gait of the tracklayers, who walked in straight lines like a gaggle of ganders (male geese) as they carried the rails to their last resting place on the ties. They choreographed their movements to ensure maximum leverage and minimum muscle stress, moving in unison to calls like “up” and “down” like dancers in a square dance. As soon as they tapped the new rails into line and firmed up linkages with “fish plates” (fissure plates), the kid with the one-horse flatcar would roll forward onto the new section even as the grown men were spiking the rails in place—10 spikes to a rail, three taps to a spike. When the flatcar ran short of ties and rails, the gandy dancers would heave it off the tracks, and the boy and the draft horse would head back down the right-of-way for another load of ties and rails. Once the route had been graded, laying a mile of track a day was no trick at all.

Behind the tracklayers and the kid with his one-horse flatcar came the construction train, offering bunkhouses for the gandy dancers, a kitchen, a carpentry shop, a general store, managers’ offices, a telegraph office and a saddlery to repair leather goods, with storage cars for food and tank cars for water. Supply trains came and went on the single lane of track behind the construction train, providing additional shelter in the event of very rare Indian attacks. The advance surveying and grading crews were at greater risk, but protecting them were Frank and Luther North’s Pawnee Scouts, Indians who were themselves redoubtable Indian fighters. The boxcars also contained about 1,000 rifles and plenty of ammunition. Gandy dancers were far more likely to die by industrial accident, disease or internecine homicide than by Indian attack.

Who were “the Irish” who built the Union Pacific? Actual Irishmen probably represented the single largest ethnic group, but they were collectively outnumbered by Union and Confederate veterans, freed slaves, Mexicans and Germans—most of this last group typically well versed in the skilled trades widely taught in the German states to boys who weren’t landowners or sons of the educated. Broadly, most Irish immigrants landed day-labor jobs either because they didn’t know how to read or because their religion and accents aroused ethnic prejudice, while most Germans landed day-labor jobs because they hadn’t yet learned to speak English. Members of either group who sought greater risks and had no need to send money home usually joined the Army instead. Union Pacific wages of $3 to $4 a day was excellent pay in a time and place when soldiers earned $13 a month.

The idea that New York gangster types would want to swing a pick in Indian country when they could pick a pocket on the Bowery was plumb silly. Most of the Irish workers were probably shy country-bred boys and men, fond of liquor, capable brawlers in a pinch, but not very promiscuous. Irish girls sometimes cast spells on their men to keep them faithful by sewing menstrual bloodstains or pubic hairs into the seams of their homemade shirts. The rampant promiscuity of the Hell on Wheels shantytowns and tent cities that followed the head-of-tracks was a fact of life. But the denizens of these establishments probably did a lot more business with Civil War veterans and fun-loving Mexicans than with recent immigrants from the Emerald Isle. Dr. Thomas Lowry estimates that one-third of the veterans who died in old soldiers’ homes were finished off by “social diseases.” Hell on Wheels would have attracted these men when young. Most sons of a chaste but bibulous Irish culture probably didn’t get past the first saloon.

The gandy dancers of legend subsisted on fresh or salt beef, bread and potatoes, washed down with coffee or raw whiskey—actually not such an unhealthy diet. Potatoes contain a natural antiscorbutic, and with either meat or whole milk, spuds constitute a nutritionally complete diet. But an inventory from the company store shows salted codfish, peaches, cherries, raisins, currants, apples, tomatoes, eggs, beets, turnips and spices, notably Worcestershire sauce to make the beef palatable.

When the Union Pacific reached Utah, management put out a million-dollar call for Mormons to work on the railroad, and these hard-working and habitually sober people comprised a sizable contingent of gandy dancers—free of the vices subsequent chroniclers have assumed went with the territory when working on the railroad.

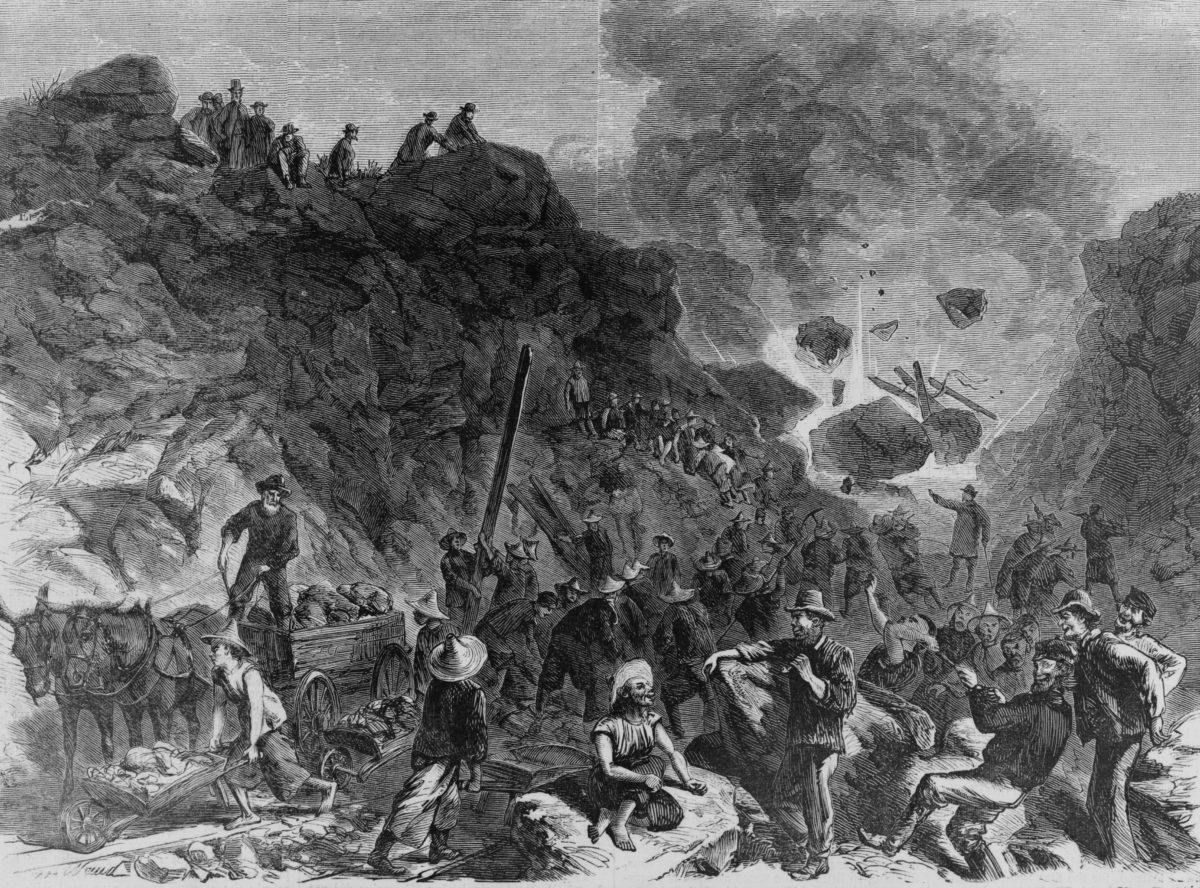

Mormon crews, incidentally, put the spike to one of the most frequently related railroad tales: the supposed blasting feud between Irish and Chinese workers. Union Pacific’s Grenville Dodge told a reporter of the Irish-Chinese rivalry 30 years after the fact. Allegedly, it led to rock-throwing and club-swinging, then to an incident in which the Irish, grading above a spot where the Chinese of the Central Pacific were at work on a parallel grade, blew up a cliff face and buried a number of Chinese. The Chinese soon got into position and returned the favor, burying a number of Irishmen. The Irish then called off the feud. But Dodge had been in Washington, D.C., not Utah, when the purported exchange took place. Also, the Union Pacific stopped grading at Promontory in Utah Territory; the Central Pacific at Toano, Nev. Only the nonbelligerent Mormons participated in grading the spot where the blasting feud supposedly took place.

Irish and Chinese laborers, in fact, are known to have worked harmoniously on the Central Pacific, on which the graders and tracklayers were usually Chinese and the foremen and teamsters Irish. The blasting feud may have been the most durable and most pernicious aspect of the gandy dancer myth.

John Koster is the author of Custer Survivor. Minjae Kim assisted on the research.

Originally published in the April 2010 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.