There’s a small parking area off a narrow road that winds through the Tennessee hill country about 75 miles west of Nashville. From it, a path leads down a rather steep hill into a wooded ravine. At the end of the path there’s a large boulder etched with the names of Patsy Cline, Hankshaw Hawkins, Cowboy Copas and Randy Hughes. At this place, on March 5, 1963, all four died in the crash of N7000P, a 1960 Comanche 250. It’s probably the most famous crash involving a Comanche, the same type of plane that I fly.

Cline’s death at the age of 30 shocked the music world. She seemed destined for bigger things. Born in 1932 as Virginia Patterson Hensley in Winchester, Virginia, Cline had become a huge star, with a string of hits that included “Crazy,” “I Fall to Pieces” and “She’s Got You.” She died just four years after the crash of a Beechcraft Bonanza killed rockers Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and Jiles Perry Richardson Jr. (better known as the Big Bopper), which fueled much speculation. Why would Cline fly in such a small aircraft? Was the pilot qualified? Was the airplane airworthy? How safe are such planes?

In retrospect, given that most celebrities travel today in private Gulf-streams or chartered jets, the idea of a major star traveling in a single-engine plane seems almost ludicrous. But the crash says as much about the times in which it occurred as the circumstances surrounding it.

The late 1950s and early ’60s were a time of great optimism for general aviation. Beechcraft, Cessna, Piper and a host of other companies vied for what seemed a limitless market. Manufacturers delivered a total of 6,750 new general aviation aircraft in 1962. Compare that to a total of 2,630 aircraft in 2021. (That latter number includes business jets and turboprops; only 1,393 of the total were piston-powered airplanes.) Among those who caught the flying bug in that earlier era were a number of celebrities. A few, such as Jimmy Stewart, Robert Taylor and Gene Autry, honed their flying skills in World War II. Many other stars, including George Kennedy, Cliff Robertson and Clint Eastwood, took it up on their own.

Flying was very different then. Global positioning system (GPS) navigation wouldn’t be available for another 30 years. The Victor airway system—a network of pathways plotted for low-level flights—had been commissioned only 11 years earlier, in 1952. Most private pilots were strictly VFR (visual flight rules), navigating by dead-reckoning or by a combination of pilotage and radio-based VOR (VHF Omnidirectional Range). Aeronautical charts still marked commercial AM radio stations that pilots could tune in, which allowed them both to navigate and keep up with ball games. Transponders were not yet standard equipment and few aircraft had distance measuring equipment (DME). Most weather briefings were conducted pre-flight in person at one of hundreds of on-field Flight Service Stations located around the country. The system of VFR flight following, when pilots can request departure or approach information from air traffic control (ATC), was not yet established, and many pilots avoided interaction with ATC unless absolutely necessary, filing a flight plan only as a basic precaution.

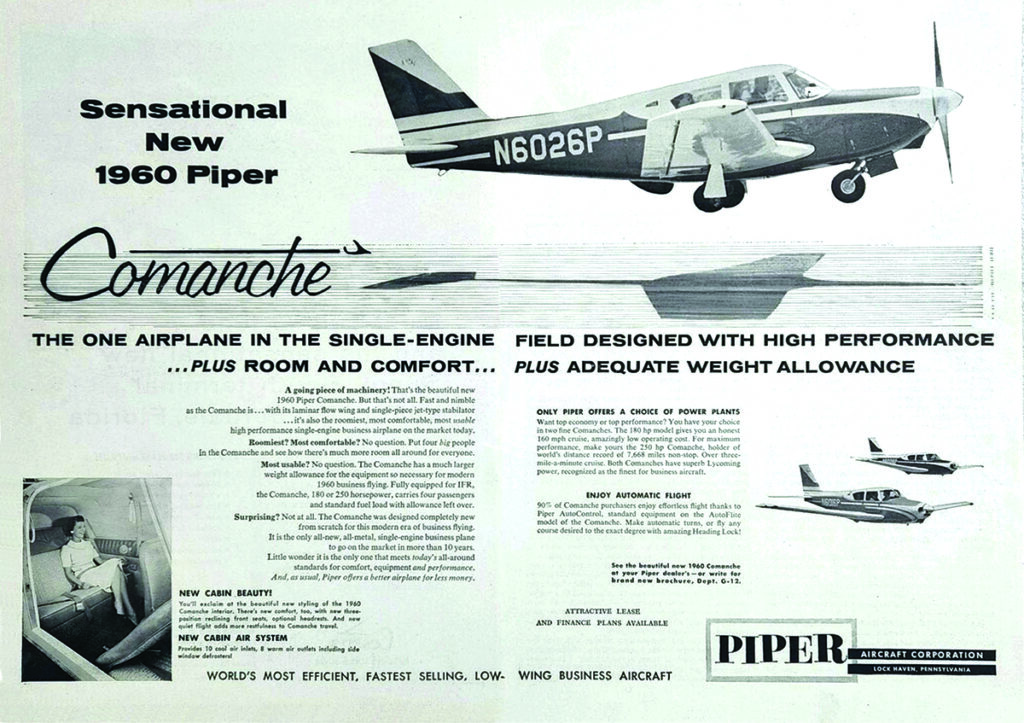

Ramsey Dorris Hughes, also known as Randy, was a Nashville musician and Patsy Cline’s close friend and manager. A relatively new pilot, he received his license in May 1962. Soon after, he bought N7000P, a green-and-yellow 1960 Comanche 250 (the same year and model as the airplane my father bought new in 1960). It was a distinctive craft, with a garish paint scheme that featured wide stripes along the fuselage and an odd-looking widget shape decorating the tail. (My dad’s airplane was blue and yellow.)

Built at a time when airplane manufacturers were promising “an airplane in every garage,” Piper’s first all-metal single-engine craft seemed designed to put automobile drivers at ease with the idea of flying. The Comanche 250 had a 250-hp O-540-A Lycoming engine and retractable landing gear. The interior had the look and feel of a sedan; the airspeed indicator was marked in miles per hour rather than the unfamiliar knots; and the owner’s manual was ridiculously thin, excluding topics that might turn away prospective pilots—like emergency procedures. The standard package for the 1960 Comanche did not come with VOR receiver, but Hughes’ 7000P had an upgraded package. That included the Narco Omnigator Mk. II Nav-Com system, a voice communication and navigation system that was reliable but bulky and awkward to use by today’s standards.

Hughes’ primary instructor was a man named George Mummert, a well-known and respected instructor in Nashville. Mummert also gave lessons to singer Jim Reeves, who ironically died in a plane crash a year after Cline did. Though the two crashes led to some speculation about the quality of Mummert’s instruction, he was considered a stern taskmaster and stickler for doing things right.

Hughes was an active pilot. Between March and May 1963, according to the Civil Aeronautics Board report, he logged a total of 117 hours in the Comanche. Some of those flights were for business, flying Cline to shows in San Antonio or Iowa. On other occasions, he’d fly his client to Pensacola for a day at the beach and some much-needed R&R. Cline did not seem to be a nervous passenger. If anything, having been in a serious automobile accident in 1961, she seemed more at ease in the air than on the highway.

Of Hughes’ total flying hours at the time of the crash, he had logged only three at night, presumably all during his primary training. Also, he did not have an instrument rating, nor had he logged any hours in pursuit of it.

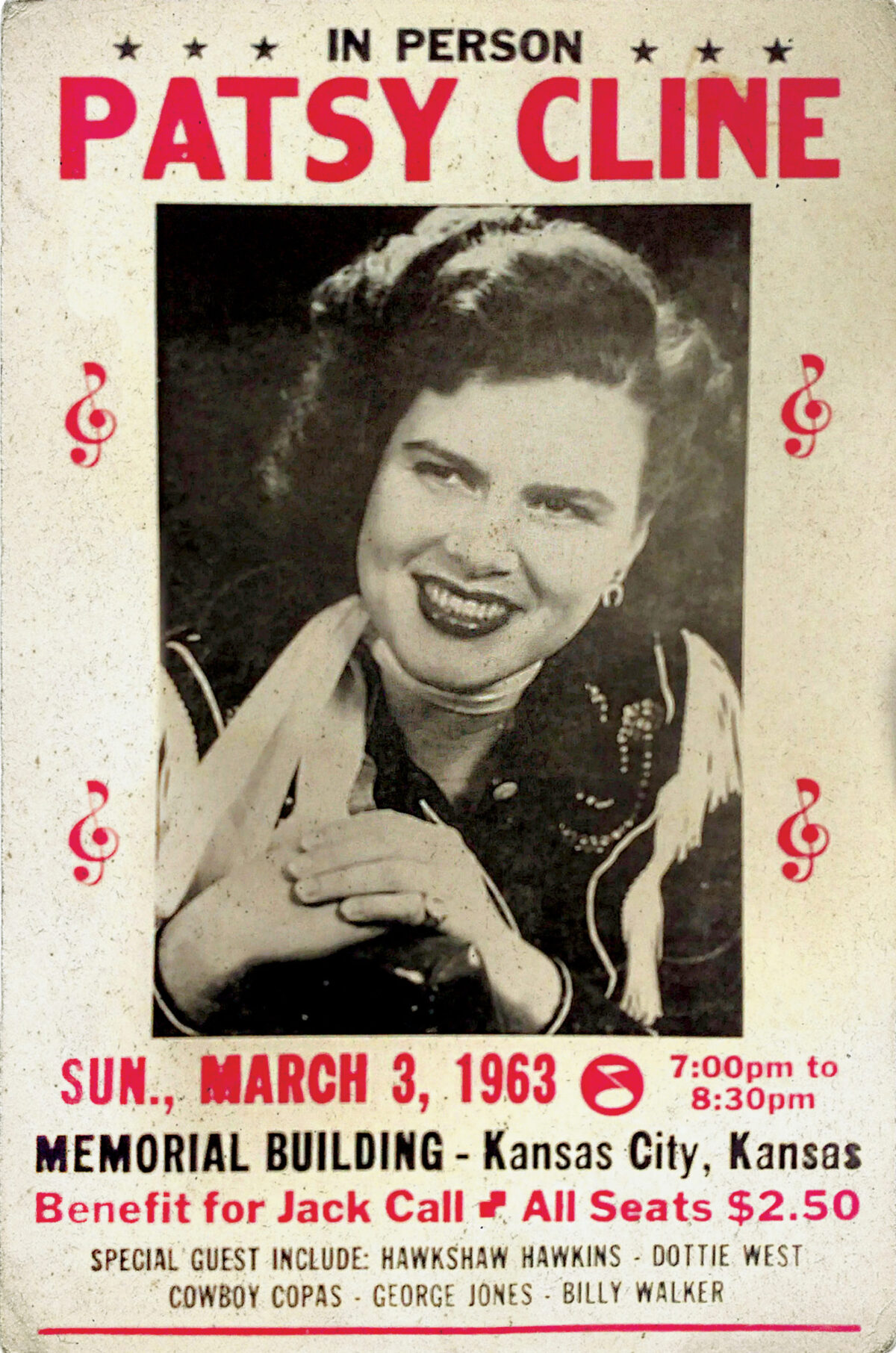

Not long after her hit “I Fall to Pieces” made the pop and country charts, Cline agreed to a hastily arranged appearance in Kansas City, Kansas, on March 3, 1963. With back-to-back shows in New Orleans and Birmingham, Alabama, the days before the Kansas City gig, the only way she could make the show in time was via the Comanche, according to the Ellis Nassour’s 1993 biography, Honky Tonk Angel. The weather was cold and blustery, typical for that region at that time of year. Upon arriving at the former Kansas City Fairfax Municipal Airport, Cline complained about how cold it was sitting in the rear seat of the airplane (a situation with which a lot of Comanche passengers can sympathize).

After the shows, Cline was eager to get home to Nashville, Tennessee. She had come down with the flu, and her husband was taking care of their young children, one of whom was sick. The next morning, however, the airport, which lay in a bend of the Missouri River, was fogged in. Another musician couple offered Cline a ride home in their station wagon, but she turned them down, perhaps figuring the weather would soon lift. It didn’t, forcing Cline, Hughes and musicians Harold Franklin “Hankshaw” Hawkins and Lloyd Estel “Cowboy” Copas (Hughes’ father-in-law) to spend an extra night in a nearby motel.

The next morning the weather was only marginally better. A front had moved through, creating a line of showers and storms along the flight path home. The straight-line distance between Kansas City and Nashville is 417 nautical miles, or about a three-hour flight—easily within the range of the Comanche with its 60-gallon tanks. But low clouds grounded all planes. Hughes shuttled between the motel and the airport for updates on the weather.

By noon, the ceiling had lifted a bit and the temperature rose to 43 degrees. Hughes made his decision. The four checked out of the motel at 12:30 p.m. and headed to the field. Airport owner Eddie Fisher later recalled that Hughes seemed “level-headed” despite Fisher’s warnings about the weather. Hughes assured Fisher, saying, “If I can’t handle it I’ll come back and fly west or go someplace else.” The four climbed aboard Hughes’ Comanche, with Cline sitting in the rear seat behind the pilot, and took off at about 1:30 p.m.

Instead of turning on course to the east, however, Hughes headed due south, most likely trying to work his way around the weather and perhaps following the local highways (Interstate 49 had yet to be built). He flew across Missouri and into Arkansas and after about an hour’s flight he landed in Rogers, where he reportedly checked the weather again and took on fuel. Little Rock, about 130 nautical miles to the southeast, was reporting rain and sleet.

Hughes filed no flight plan, so his exact route cannot be known. Given the weather, he likely had to dodge clouds and precipitation flying under the overcast. He next landed in Dyersburg, Tennessee, about 230 nautical miles to the east, at around 5:15 p.m., a flight of a little over 90 minutes. While Cline and the other passengers ducked into an on-field restaurant, Hughes checked in on the Flight Service Station.

A briefer told Hughes that continued flight was not recommended. Visibility was down to five miles in a mixture of rain and light snow, with winds of 20 knots, gusting to 31 knots with heavy turbulence. Conditions were marginal at best, and the low visibility and overcast would obscure obstructions such as hills and radio towers. The weather in Nashville, an hour away, was below VFR minimums and was likely to deteriorate further before any improvement.

Hughes asked what time the sun set (about 5:56 p.m.) and was told that the overcast would make it darker much sooner. Hughes was not night current and thus not legal to carry passengers after dark.

Hughes then left the station and went to the restaurant to tell the others. There was a brief debate, but by all accounts it was obvious that Cline really wanted to get home. Hughes called his wife in Nashville to ask her about the weather conditions there. She told him that it had been raining and stormy all day, but the rain had stopped, “and it looked as if it were trying to clear up,” she later recalled. Hughes may have misunderstood this to mean the weather had cleared up or interpreted it to mean the weather was clearing up. Whatever the case, he told the others to get ready to leave, then went to pay for the 27 gallons of fuel he took on.

Airport manager William Braese told investigators he urged Hughes to stay over, that the weather for a non-instrument rated pilot was not good, especially for a flight at night, over a rural area with no lights. He even offered to loan Hughes his car to drive to Nashville and said he would fly the airplane back the next day. But Hughes remained undeterred.

Crash investigators often refer to “tunnel vision,” a mental state in which a pilot becomes so fixated on a goal that he or she blocks out all other information. Hughes, facing the pressure to get his prized client home after all the delays getting out of Kansas City, and after the stress of scud-running his way across the south-central U.S. that afternoon, might have been suffering from such a state. When interviewed by the Civil Aeronautics Board, Braese said everyone appeared exhausted, including Hughes.

Just before departure, Hughes asked for another weather observation. He then took off into the dusk at 6:07 p.m. About 20 minutes later, according to the investigation report, a witness near Camden, Tennessee, heard a low-flying aircraft. He observed the airplane as it descended out of the low overcast at an estimated 45-degree nose-down angle. He then heard a dull crash.

The debris was strewn across a path 166 feet long and 130 feet wide. The engine was buried in a four-foot crater. The violence of the impact left nothing intact. Plane, contents and occupants were scattered in pieces. News of the crash quickly spread. After the bodies were removed, looters descended onto the scene, taking away clothing, jewelry, pieces of musical instruments and parts of the Comanche. On YouTube you can find a video of a reporter interviewing a local man who recalls the crash and then proudly displays one of the plane’s control yokes.

Investigators found nothing to indicate anything was wrong with the airplane. The engine was developing normal power at the time of the crash. The board concluded that the “non-instrument pilot attempted visual flight in adverse conditions, resulting in loss of control” and blamed the “judgment of the pilot in initiating flight in the existing conditions.”

On one level, the circumstances of this crash are an old story, one that combines poor weather, pressure to get home and pilot hubris. Time has shown that there’s really nothing to prevent people from going up in small aircraft and killing themselves. Like Hughes, my father never got his instrument rating, but my father was cautious to a fault. I remember being stuck for days waiting out the weather—in Douglas, Arizona, in Hermosillo, Mexico, in St. Louis and in San Diego. There were times we eventually boarded an airliner to get where we wanted to go, and my father would ferry the plane home another time. One truism about flying small aircraft that hasn’t changed over time is that if you absolutely must be somewhere, use the airlines.

But things have gotten better since then. Technologies such as GPS, onboard weather reporting and cheaper and more reliable autopilots have improved pilots’ situational awareness and reduced their workload. That, combined with better training and procedures—including the requirement of transponders in controlled airspace and the availability of ATC flight following—along with an industry-wide emphasis on safety (partly the result of the liability crisis of the early 1990s) have all made flying safer. The numbers bear this out. In 1963, the accident rate per 100,000 flying hours was 31. By 2009, that number had dropped to 7.2. That isn’t to say Randy Hughes would not have crashed had he had access to all these tools—only that he would have had a better chance not to. In that case, Patsy Cline might have become an even bigger star.

Tom LeCompte is a freelance writer, airplane owner and longtime pilot based south of Boston. When not writing or researching stories, he’s airborne somewhere. For further reading he recommends Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline by Ellis Nassour.

This article appeared in the Autumn 2022 issue of Aviation History. Click here to subscribe.