In 1066, William the Conqueror crossed the English Channel from Normandy and secured his royal title of king of England following his victory at the Battle of Hastings. Centuries later, Allied troops made the journey in reverse, sailing to the sandy shores of northern France in June 1944 to liberate Western Europe from Nazi Germany.

This parallel did not go unnoticed by England’s Lord Dulverton, a tobacco magnate who had trained British Army sharpshooters during World War II. Seeking to immortalize D-Day’s fallen Allied soldiers, Lord Dulverton commissioned and bankrolled his own 20th-century version of the Bayeux Tapestry—the famed medieval embroidery depicting the Norman conquest of England—in 1968.

Dubbed the Overlord Embroidery, the work consists of 34 panels, appliquéd and embroidered with chronological scenes ranging from England’s descent into the Battle of Britain to the heroic events and aftermath of June 6, 1944. Based on designs by English artist Sandra Lawrence, who drew inspiration from period photography for added realism, the visual narrative took a team of 20 artisans from the Royal School of Needlework five years to complete. A sampling of the embroidery’s panels appears on the following pages; the 272-foot artwork is on permanent display at the D-Day Story museum in Portsmouth, England, and additional images are online.

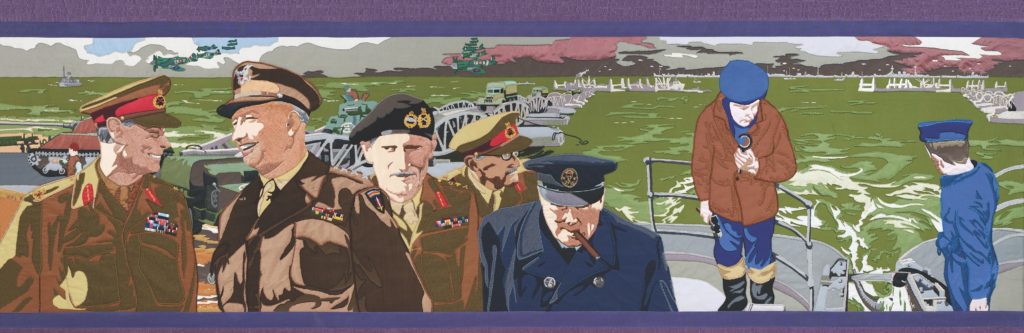

all in the details

Top brass from England and the United States paid separate visits to Normandy in June 1944, but space considerations prompted artist Sandra Lawrence to draft a panel showing Allied leaders surveying the landing beaches together. Appearing above, from left to right: King George VI, Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and Bernard Montgomery, Field Marshal Alan Brooke and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Although this specific meeting was fictional, Lord Dulverton and his advisers insisted on getting every detail correct, from the crook of Brooke’s nose and the Mulberry Harbors offshore to the correct sequence of Monty’s ribbons.

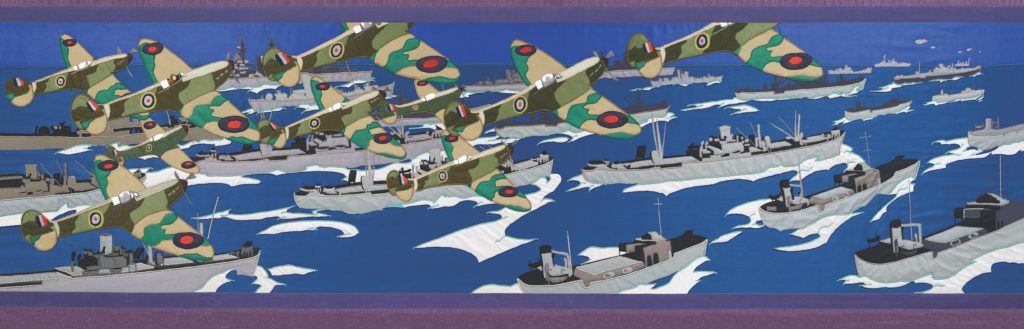

above and beyond

Most of the artwork’s panels feature short vignettes. When it came to recreating D-Day’s Channel crossing, however, Lawrence was urged to expand the scene and capture its scale “in panoramic form.” Lawrence heeded this advice and devoted multiple panels to Allied naval and air forces mid-voyage to France; the segment below shows Spitfires providing air cover for a bevy of troopships.

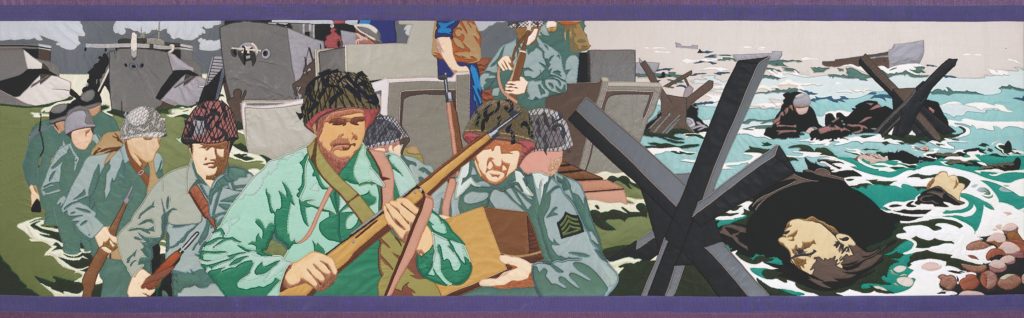

LUCK OF THE LAND

The G.I.s at left in the panel below, shown charging onto Utah Beach, suffered fewer casualties (just 197 out of the 23,000-odd men who landed there) than troops coming ashore elsewhere. Juxtaposed against a scene set at Omaha Beach, the waves dense with corpses, the contrasting vignettes emphasize how luck wasn’t always distributed equally on D-Day. One aspect that is uniform here: the soldiers’ battle dress, sewn in portions from genuine World War II army fatigues and bearing authentic regimental patches. Other panels depict British, Canadian and American troops likewise wearing combat gear partly fashioned from real-life war garb.

SEARCH PARTY

Allied troops who survived storming the beaches faced additional dangers once they reached the Cotentin Peninsula. At right, an American soldier guards several Wehrmacht POWs. The prisoner at the forefront, arms held aloft as he waits to be searched, wears an Iron Cross for bravery—but in the photo the artist used as a reference, he looks far more frightened than he does courageous.

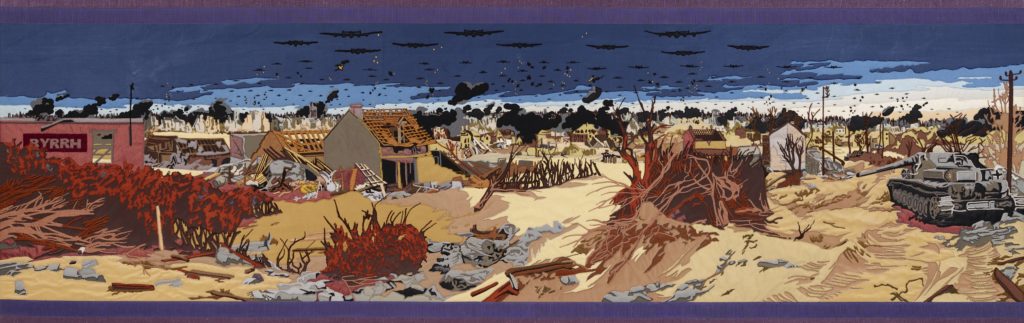

WHAT REMAINS

The scene above, which depicts Allied bombers and tanks driving German forces from the ravaged port city of Caen, composes one of the artwork’s final panels. It was, in fact, the very last to be commissioned by Lord Dulverton: while inspecting the nearly completed tableau in March 1973, he thought it still needed to illustrate the invasion’s toll on Norman towns and villages. The Caen panel was completed in early 1974; to ensure viewers recognized the scene as French, Lawrence added a painted ad for Byrrh, a French apéritif, on one of the city’s still-standing buildings.

All photos courtesy of the D-Day Story, Portsmouth, except where noted.