IN AUTUMN 1872, disaster distracted Americans from the coming November elections, and much else. A mysterious epidemic swept North America, indirectly affecting the human population by affecting directly something humans relied utterly on: horses. Barely able to move the street cars, wagons, carts, and drays that fueled every aspect of commerce, sick horses plodded listlessly in harness or were confined to stables for treatment that sometimes included the ancient remedy of bleeding. In major cities, the illness sidelined tens of thousands of horses. Veterinarians and the most experienced horse handlers could provide no cure. On October 25, 1872, a New York World headline fretted, “Is America to Be Horseless?”

The disease first struck outside Toronto late that September. As in cases of human influenza, the first symptoms were coughing and sneezing. Animals would lose their appetites and experience runny noses; bloodshot eyes; and general weakness. Infected horses barely could stand, much less perform work. “Every one of the 60 horses in the barn was affected, and such a coughing, wheezing, and blowing of noses no horseman ever heard before,” an eyewitness said. Street car horses in Brooklyn shook “like aspens despite the heavy blanket covering thrown over them…” A reporter saw horses “shivering and coughing, while a yellowish discharge dripped from their nostrils.” Infected animals, he wrote, “seem to suffer rather from weakness than pain. They stand with drooping heads and an appearance of utter listlessness.”

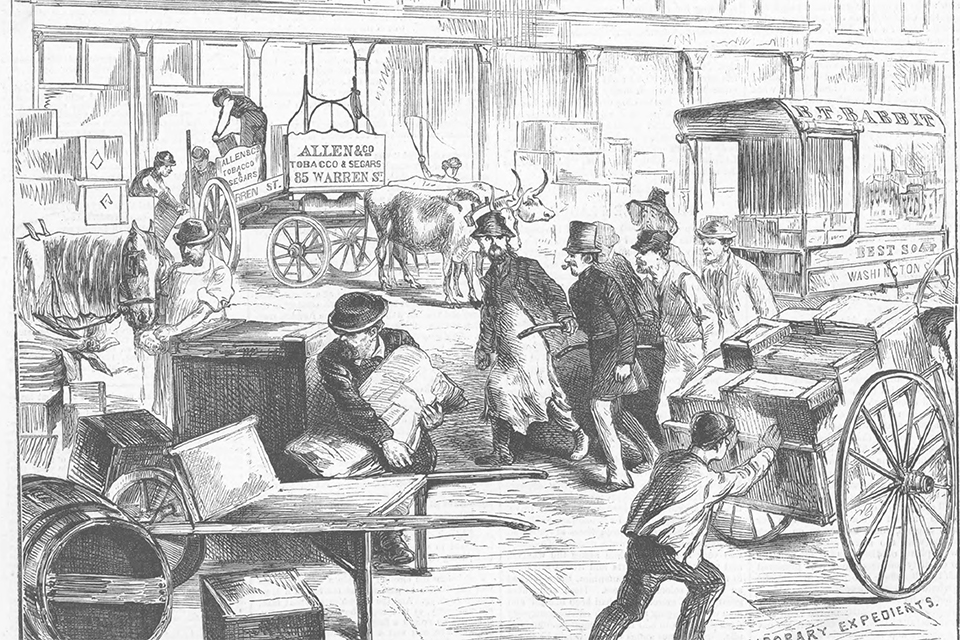

Most stricken horses had trouble staying on their feet. Mules and donkeys were also susceptible, but not bovines such as oxen. Fortunately the mysterious condition was rarely fatal.

Upon establishing itself in a jurisdiction, the malady spread very quickly. By October 8, there was in Toronto and environs “scarcely a horse in the city fit for work,” an American newspaper reported. “Merchants are unable to ship or get goods from the depots.”

The sickness crossed the southern border in early October 1872. Press reports pointed to the vector being a Buffalo man who drove his four-horse team across the Niagara River and back to attend a function hosted in Queenstown, Ontario, by Canada’s governor-general. Horses were reported to be ailing in Buffalo, New York, on October 11, and in Detroit, Michigan, by October 15. In Rochester, New York, the street railway system’s 130 horses were sick on October 21, as were 200 horses belonging to the traveling O’Brien Circus Company, then in town. According to press reports, “It was impossible to hire a horse of any kind” in Rochester. The “Canadian Horse Disease” appeared in Boston on October 20; New York City on October 21; and Philadelphia on October 26. Stricken animals usually were out of work two to three weeks; some recovered more quickly, other episodes dragged on for a month.

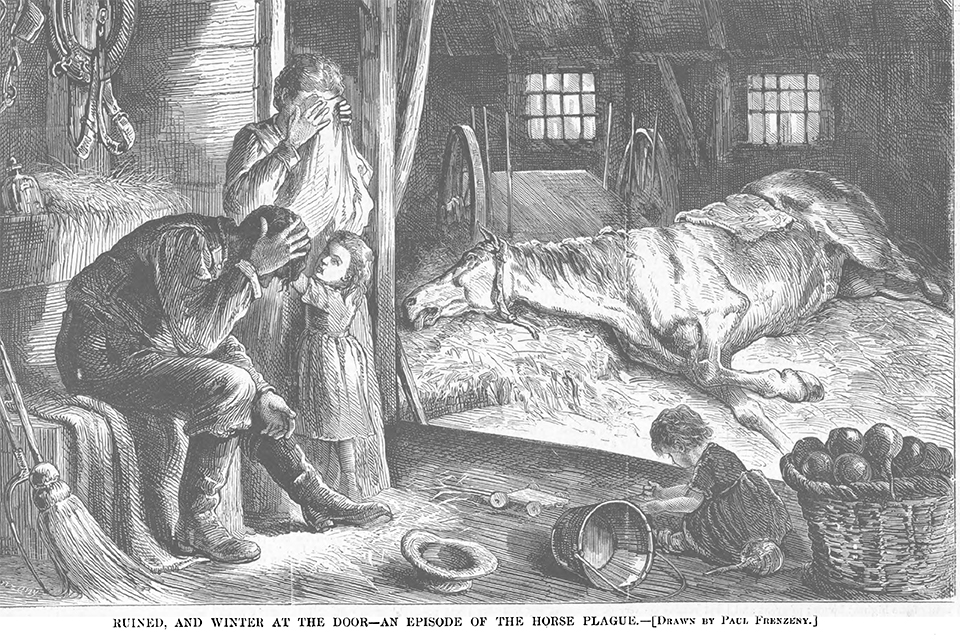

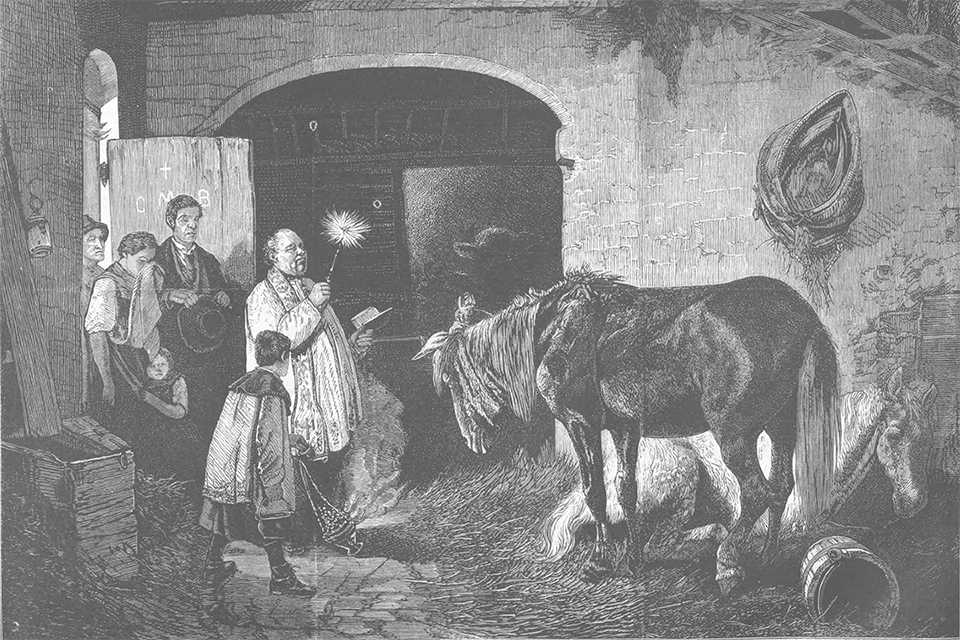

Suggestions for cures abounded. Owners draped blankets over sick horses as they recuperated in stables, and made sure to cover animals kept working. Stables reeked of disinfectants like carbolic acid and of tar, used to fumigate the premises.

Horse diets might change to apples and salted hay; other owners served bran mash mixed with potassium bromide. Some handlers dosed horses with aconite, arsenic, and mercury and other supposedly medicinal compounds now known to be toxic.

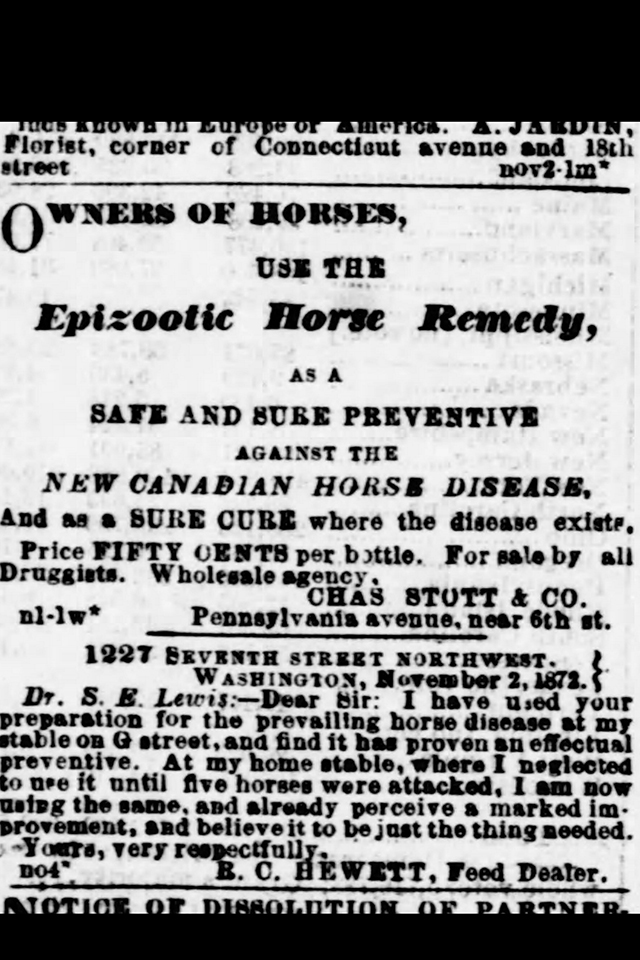

Many veterinarians warned against drastic treatments such as blood-letting or purging the sick animals with laxatives. However, other vets recommended exactly those steps. Newspapers ads touted patent medicines touted as cures.

Despite the variety and volume of media coverage dedicated to useless or harmful suggestions, many people accepted that the most effective treatment was time. “It is generally understood that the disease must have its run,” one paper wrote, noting the corollary of allowing recovering animals to rest as long as needed. Forcing partly recovered animals into harness too soon risked triggering relapses.

Professionals called the outbreak the “epizootic”—ep ih zoh ot tic— a term still used to indicate a disease epidemic affecting animals. Informally, people referred to the “horse plague,” “Canadian Horse Disease,” the “horse malady,” and “the horse disease.” Less common references included “epizooty,” “hippogrippe,” and “hippozymosis.”

The world of 1872 ran on horsepower. In cities, mass transit systems and fire departments relied on horses. Teamsters behind a horse or a team delivered goods, milk, and ice. Doctors rode or drove horses on house calls. Horses hauled from mines the coal that propelled railroads and steamships and corpses bound for cemeteries and potter’s fields.

The 1870 United States Census tallied 38,558,371 people, and 7,145,379 horses—strictly on farms, not counting animals in urban areas. New York City was home to more than 38,000 horses serving its 942,292 residents—a horse for every 25 Gothamites. By Halloween, practically every horse in New York had contracted the epizootic, idling hundreds of street cars; those that did have teams added animals to cope with excess passengers. New York veterinarian A.F. Liautard saw the disease hit there in late October. “On the morning of the 22d I doubt if there was a single animal of the equine species which was not attacked,” Liautard wrote. “Horses, mules, and even a zebra belonging to a menagerie, were affected almost simultaneously.” Envisioning a dystopian future, The Nation on October 31, 1872, wrote, “The sudden loss of horse labor would totally disorganize our industry and our commerce, and would plunge social life into disorder, [and] would threaten the lives of hundreds of thousands of human beings.”

Shippers using rail and the sea found their goods stalled at depots and on docks. Loss of a horse could paralyze a small business. The germ theory was afoot, but folk tales persisted about “miasmas” spreading disease through the air, perhaps by carrying fungal spores. Besides examining mucus from ailing animals, U.S. Army surgeon and photomicrography pioneer Joseph Janvier Woodward performed “a careful microscopic examination of the organic forms derived from the air of stables” known to harbor the epizootic in Washington, DC. Woodward found ordinary germs, nothing to indicate an agent responsible for the new ailment. The outbreak was caused by an undiscovered virus, possibly related to a strain now extinct (see “Vanishing Virus,” below).

In time observers realized infected animals spread the disease. One sick horse could infect an entire herd, especially if confined, by contaminating feed and water.

Teams of oxen suddenly were bringing premium prices for purchase or rental. Cincinnati brought the lumbering beasts in by the boatload. Oxen pulled wagons down Broadway in Manhattan. In many places, goats, dogs, and even milk cows substituted for draft horses. In Chicago, the main post office organized lines of men pushing wheelbarrows to move mail to and from the train stations. Fire engines, once small enough for gangs of men to pull, now were so large that they needed at least three horses in harness. Cities were mostly built of wood; fire was a constant threat. Boston authorities, understanding the epizootic’s implications, readied manual drag lines in place of fire engine horse tackle, and temporarily hired 500 men to stand by should engines need hauling. The epidemic seemed to ebb as quickly as it had surged, and by November 9, Boston street car companies were running on limited schedules. However, firehouse teams were still down. At 7 that evening, a four-story building at Summer and Kingston streets caught fire. Crews rushed to the scene with pumps on hand carts, but

cart-borne pumps depended on water main pressure, which was so weak that water could not reach the upper stories. By the time steam-powered pump trucks arrived, the fire had spread. Telegrams summoned fire companies from adjoining Massachusetts suburbs and towns and then from out of state. From Wakefield, 12 miles away, a “hardy and noble set of fellows” pulled their engines to the fire. Trains carried crews from much further away. The Great Fire of Boston consumed 776 buildings. City officials said the delay in containing the blaze had less to do with a shortage of horses than with a laggard response to the first reports of a fire, along with inadequate building codes and inadequate mains.

The epizootic swept in an arc, spilling south from the Northeast and the Great Lakes and along the Atlantic Coast to wheel west across the plains and the Rockies to California, also dipping into much of Central America. By spring 1873, the ague had reached British Columbia.

The initial air of dread faded. Medicines had no effect on the “epizooty,” true—but within a few weeks affected animals were able to go back into harness. Mortality was low, and most horses survived. Veterinarians found that animals succumbing to the malady, if not already in poor health, had been pushed too hard instead of being allowed to rest and recover.

The sense of crisis passed. Shortly after the horse disease appeared in San Francisco on April 18, 1873, a humorist joked in the Daily Alta California, “I think I had begun to feel a little slighted by the epizootic—it was so long in coming, but it is here at last, and California is not behind the times.” Newspapers began to run “epizootic jokes,” along the lines of jesting that “the Iron Horse”—the steam locomotive—was immune to the ailment. Another referred to former horse car passengers riding “The Foot and Walker Line.” Two enterprising fellows who set up in business pulling a wagon on foot amused potential customers with a placard reading that they could not contract the epizootic.

Temporarily unemployed teamsters and drivers had the public’s sympathy. A benefit show at the Grand Opera House in Baltimore, Maryland, raised money to help the men through the fallow times.

Conditions in the cities of the East had returned to normal by New Year’s Day 1873, but not so out west, where the horseflesh shortage isolated town upon town and played havoc with the U.S. Army, then fighting the Apache in Arizona and the Modoc in California. Until their mounts recovered, cavalrymen marched and fought on foot.

Little of North America north of Panama was spared. Prince Edward Island, in the Canadian Maritime Provinces north of Maine, avoided the disease because winter ice cut off contact with the mainland. Vancouver Island successfully maintained a quarantine. Key West and most other Caribbean islands imported few horses and so avoided the disease. Cuba, which then had strong trade links with the United States, was hit hard by the epizootic.

New York City’s Bureau of Sanitary Inspection of the Health Department counted 1,412 horses killed by the epizootic in fall 1872. Another 534 horses died, probably weakened by exposure. the bureau estimated that the disease had killed 3.7 percent of New York City’s horses. There and in other communities people studied options should the disease recur. Proposals were floated for a line of cheap passenger steamers to circumnavigate Manhattan. Towns looked at “dummy engines”—small steam-powered vehicles resembling street cars—but weight, noise, and pollution cancelled out that alternative. “There is an abundance of genius in this country which, if it can only be brought to bear, will readily discover a solution for this problem,” Scientific American wrote on November 16, 1872.

In 1873 San Francisco began offering cable car service, an approach unsuitable for many cities because of heavy start-up and maintenance costs. The 1880s brought electric trolley cars. By 1902, electricity was powering 97 percent of street car systems in the United States. The internal combustion engine eliminated the need for horses for transportation, shipping, and public safety. Nothing again ever affected the United States as did the Great Epizootic of 1872.

Vanishing Virus

Veterinary science still has not explained the 1872 equine pandemic in North America, according to Dr. Howard H. Erickson, professor emeritus of physiology at Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “I don’t think the exact cause of the 1872 equine epizootic has been identified,” he said, noting that around 1930 previous outbreaks of equine influenza were traced to particular strains of virus, one of which is thought to be extinct. In a government report he compiled on the 1872-73 outbreak, veterinarian Dr. James Law cited epizootics as early as one in Sicily in 415 BCE that struck Athenian invaders’ mounts and an American outbreak in 1698. Outbreaks occurred in 1880-81, 1900-01, and 1915-16, Dr. Erickson said. Australia experienced no equine influenza until August 2007, when within three months the illness infected 10,000 horses. Eradication there cost about $1 billion.

The 1872 episode spread so rapidly in large cities and towns thanks to the era’s large horse populations. “The disease was spread along transportation routes, especially railroads. The horses were kept in large livery stables, some like large four-story hotels, which permitted easy transmission of the disease,” Dr. Erickson said. A little-known November-December 1872 outbreak of avian influenza in the United States may have contributed to the equine crisis, he said. That epizootic killed poultry, prairie chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese. The Great Epizootic “demonstrated how important the horse was in America in everyday life in agriculture, industry, and transportation,” Dr. Erickson added. “There was no treatment for the equine influenza epizootic other than rest and supportive therapy. Veterinary medicine was in its infancy in the U.S. in 1872 and some of the treatments, such as bleeding, did more harm than good.”