While Dirk Warner toils on his 127-acre farm—the heart of the Cumberland Church battlefield—he often envisions April 7, 1865. Cannons boom, musketry rattles, battle smoke lingers, soldiers shout, blood flows. Then a spade plunges into the rich Virginia earth. A soldier rolls a friend into a grave. The cycle of war and death. How benumbing. How timeless.

Warner plans to be buried on the battlefield, too—“over by those redbuds,” he tells me as we walk his hallowed ground. Until then, Warner has a battlefield to nurture, protect, and interpret. Artifacts to unearth. A battle book to write. Dreams to turn into reality. A mystery to solve. I have one, too:

Why did it take me so long to hear about the Battle of Cumberland Church?

Before my journey to rural, south-central Virginia, I knew nothing about this battle fought in the war’s waning days. The five-hour brawl five miles north of Farmville became the last bullet point on Robert E. Lee’s military resume, his final victory. It resulted in 900 casualties—650 Union and 250 Confederate—but earned only a brief mention in the Official Records. Two days later, Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

“History makes but little mention of the battle … as events of greater importance followed so closely,” a Union veteran recalled, “but the participants know that troops never fought more valiantly than did Lee’s soldiers in their last effort when they repulsed the assault of the veterans of the 2d Corps.”

The previous night, I meet Warner for the first time to get a bead on him and the lay of his land. I step into a pile of cow manure but remain unfazed. It’s clear almost instantly this will be an epic visit.

Warner is a cattle farmer and a longtime producer and director for a Richmond TV station. We bond over a mutual enthusiasm for Civil War history. He introduces me to his Siberian Husky and American Eskimo mix named Izzy, who wants to kiss me. I shoot a selfie with his pet black Angus steer named Nibbles.

Until his death in 2010, Warner’s father-in-law, Dr. Woodrow Wilson Taylor—a veterinarian and World War II vet—owned the farm and lived in the post-battle house on the property. Warner lives in Doc’s place now with his wife, Jane.

“He made two requests of me when I married his daughter,” Warner says of Doc. “Look after her and look after his place.” No problem. Married since 1992, Warner still cherishes Wilson’s farm.

“Sacred ground,” he calls the battlefield. “Incredible.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As we walk the farm on a frosty morning, Warner shows me where Union troops formed. Andrew Humphreys, the 2nd Corps commander, made his headquarters here. U.S. Army cannons belched iron and death from the farm.

Confederate General William Mahone—all 5-foot-6 and 100 pounds of him—made his headquarters a mile away at Cumberland Presbyterian Church. The commander of Lee’s rearguard may have sought aid from a higher power. The Yankees outnumbered “Little Billy” and the rest of Lee’s army at Cumberland Church by nearly 2-to-1.

Cumberland Church, a brilliant, white beacon in morning sunlight, still holds services. But don’t bring your metal detector. “No Relic Hunting,” warns a sign out front.

“See that high ground. The Confederates commanded all that.”

As we stand in a field in front of his house, Warner points into the distance, to a ridge beyond Bad Luck Creek and the Jamestown Road. That’s where Rebel soldiers manned a strong line. Warner’s sister-in-law sold land there that encompasses part of the Confederates’ position to the American Battlefield Trust, protecting it forever.

Across Jamestown Road, at the apex of a Confederate line shaped roughly like a horseshoe, Colonel William Poague placed an artillery battery. Rebel gunners gave the Yankees “hell with grape and canister trimmings thrown in,” a Union veteran recalled. Remains of earthworks stand in a front yard of a modern house there.

Near the corner of Jamestown and Cumberland roads, 200 yards from Warner’s farm, hand-to-hand fighting broke out at the Huddleston place. The owner hid in the hearth of a fireplace with a slave during the battle, according to local lore.

To bring this obscure battle into focus, Warner mines regimental histories, manuscripts, and soldier letters—anything he can find—for a book he wants to write. He mines his battlefield, too. In 1989, Warner began finding Miniés while digging post holes on the farm for “Doc.” He has since unearthed between 2,000 to 3,000 bullets—15 different varieties in all, including a rare Confederate Whitworth round.

“See where those cows are?” Warner points to ground near a tree line. “I found the Whitworth, a medical phalange, and a picture frame right there. Confederate shelling got so bad here, the Union soldiers had to vacate.” Fifty feet from his front door, Warner uncovered a Union spur. Near it, he found a beat-up U.S. belt buckle.

“See that humpy area.” Warner gestures toward the middle of a field. “A Confederate cavalry guy got killed out there. Found a whole bunch of Richmond Lab carbine bullets in the same spot. Someone lost an ammo pouch.”

Warner bags most artifacts he finds for storage in bins in his house. He displays dozens of the relics in his home office. Only one other person may relic hunt on his battlefield—a friend who scours the fields with Warner and shares his passion for the battlefield.

“Everything he finds here, stays here,” Warner says.

Warner points out the “S” curve of an ancient stretch of the Old Jamestown Road that snakes through his battlefield. To our right, stood a thick growth of pines in 1865. Shortly before advancing, officers in the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery peeked from the edge of those woods.

“Boys,” a New York captain said, “there’s another wagon train for us over behind the rebel lines.”

The Federals advanced over an open, rolling field on Warner’s farm—“no man’s land,” he says. The soldiers halted briefly in a dip and charged as they closed to within 250 yards of their well-entrenched enemy.

Confederates answered Yankee cheers with the Rebel yell and sheets of lead and iron. Some Union soldiers reached the entrenchments and “fought to the death.” The entire 5th New Hampshire color guard fell. The Yankees fell back.

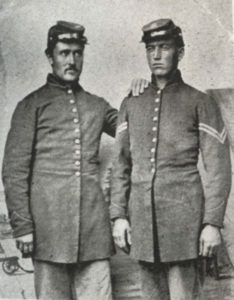

Sergeant John C. Moorehead of the 148th Pennsylvania and his friend, 24-year-old bugler Joseph Harrison Law, surveyed the battle next to each other from astride their horses—probably on the very ground where Warner and I stand near the Old Jamestown Road.

Law, a blue-eyed, light-haired farmer, had enlisted in the 148th Pennsylvania in Punxsutawney, Pa. He served in Company E with his younger brothers, Charles and Daniel. He also went by “Harrison” or “Harry.” Jovial and organized, Law seemed a natural for the army.

Shortly before he rode into battle at Cumberland Church, Harrison Law said he was eager to return to his 22-year-old wife, Mary, and four-year-old son, Carl. He had not seen them since his enlistment in August 1862. “Lee is on his last legs,” he told the regimental chaplain. “He will surrender in a day or two and then we shall soon get home.”

Shortly after Law finished his bugle call to rally the 4th Brigade, a Confederate artillery shell or solid shot carried away the top of his head. Moorehead leaped from his horse, plunged the brigade flag into the ground, and pulled his friend from his saddle. The bugler became the 210th—and last—soldier to die in the hard-fighting 148th Pennsylvania during the war.

Moorehead buried Law on the battlefield. Later, he presented Harry’s blood-spattered bugle to his brothers, who gave it to his widow. Law’s remains, however, never made it back to Pennsylvania. Moorehead died shortly after the war, leaving the location of Law’s grave a mystery.

“We know where he’s not buried,” Warner says. He stands in a shallow area in a thin patch of woods, yards off the Old Jamestown Road. In 2021, Warner had deployed ground-penetrating radar to try to locate Law’s remains. Nothing turned up, but he suspects the bugler rests near the “S”-shaped road.

Earlier that year, Warner had connected with Law’s great-great- grandson, who supplied him with copies of dozens of wartime family letters and other information. Weeks after my visit, he walked the ground with Warner—a surreal, emotional experience for both.

On the night of April 7, Ulysses Grant—commander of all U.S. Army forces—sent a messenger through the lines to Lee: It’s time to give up. Lee asked James Longstreet, his “Old War Horse,” what he thought. “Not yet,” the lieutenant general said.

“That messenger rode right out here along the Jamestown Road and delivered the message by torchlight,” Warner says. Later that night, Lee’s army withdrew by light of bonfires in the woods beyond Bad Luck Creek.

The Army of Northern Virginia could have surrendered right here. But no historical markers designate the battlefield. “This place is forgotten,” Warner says.

And so Dirk Warner dreams that someday, perhaps after both he and Jane rest in graves near the redbud trees, this unheralded battlefield becomes a national park, his house the visitor center and museum. Relics unearthed on the farm become its centerpiece.

Meanwhile, he will admire the warm glow of battlefield sunsets and think of the stories that linger on his farm like wisps of musket smoke.

“This place,” he says, “is so humbling.”

John Banks, author of two Civil War books, has another one coming in 2023. Check out “A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime” (Gettysburg Publishing) for more on Cumberland Church and stories about Andersonville, Antietam, and more.