The Minié ball, or Minie ball, is a type of bullet used extensively in the American Civil War. The muzzle-loading rifle bullet was named after its codeveloper, Claude-Étienne Minié.

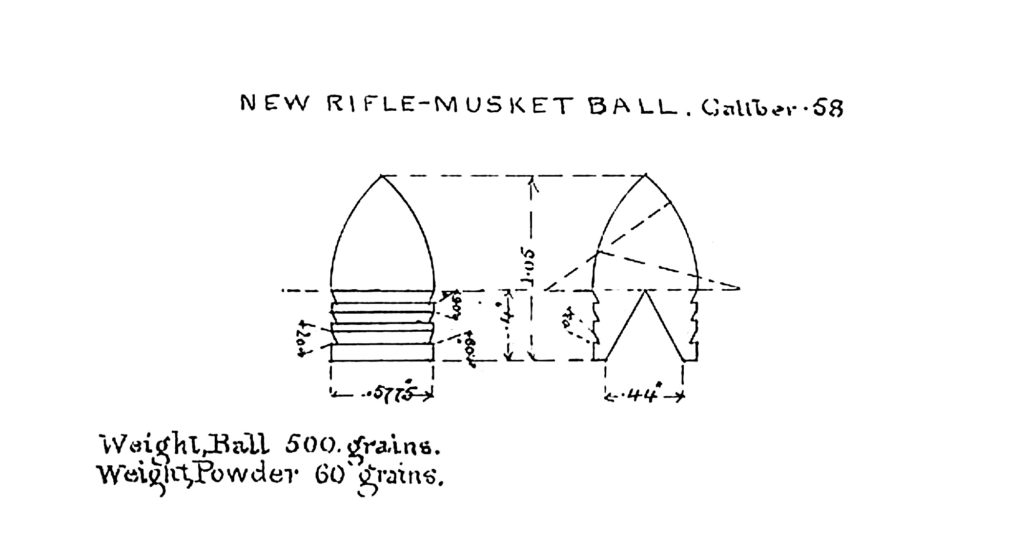

Although the Minié ball was conical in shape, it was commonly referred to as a “ball,” due to the round shape of the ammunition that had been used for centuries. Made of soft lead, it was slightly smaller than the intended gun bore, making it easy to load in combat. Designed with two to four grooves and a cone-shaped cavity, it was made to expand under the pressure to increase muzzle velocity. When fired, the expanding gas deformed the bullet and engaged the barrel’s rifling, providing spin for better accuracy and longer range.

Its design dramatically increased both range and accuracy, which has long been accepted as the reason for the high number of casualties in the Civil War. Some recent historians, however, question that because accuracy also depends on the soldier who pulls the trigger, and throughout the Civil War (when target practice was minimal), the combatants tended to aim too high.

History of the Minié ball

Recommended for you

Prior to the development of this new ammunition and weapons designed to use it, “rifles” were essentially smoothbore muskets with much longer barrels, such as the famed Pennsylvania or Kentucky rifle of the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. They were cumbersome, slow to load, and couldn’t be used with a bayonet, all of which limited their use to a few special units. Some muskets were created with a type of rifling, but the problem of providing a tight enough fit for the load within the barrel did not permit the true rifling that would come as a result of the Minié ball.

In the 1830s, Captain John Norton of the British 34th Regiment was serving in India. Some local tribes used blowguns, and Norton observed the base of their darts was made from pith, the spongy wood from the center of tree trunks. This pith expanded when a person blew into the blowgun’s tube, closing the space between the tube and the dart to give a tight seal that increased the dart’s range.

Based on this principle, Norton developed a cylindrical bullet with a hollow base in 1832. His design was improved on in 1836 by a London gunsmith named William Greener, who created an oval-shaped bullet, one end of which had a flat surface with a small hole drilled into it. This hole traveled through most of the length of the bullet and was covered by a conical plug with a round, wooden base. Upon firing, the plug would expand to prevent gases from escaping—essentially the same principle as the blowgun dart.

An old saying holds that militaries are always preparing to fight the previous war; i.e., they tend to be hidebound in sticking with proven tactics and technologies instead of looking ahead. Perhaps that is why Britain’s Ordinance Department rejected the new ammunition, despite a successful test by the 60th Rifles in August 1836.

Claude-Étienne Minié, Inventor of the Minié Ball

The design of Norton and Greener was taken a step further by two French army captains, Claude-Étienne Minié and Henri-Gustave Delvigne, who in 1849 created the conical, soft-lead bullet with four rings, and a rifle with a grooved barrel to go with it. Delvigne, who would go on to codesign several models of revolving pistols, had earlier created a conical bullet design, but Minié made the projectile smaller and longer, easier to load. At the time, French troops were facing Algerians whose long rifles outranged French muskets, and the invention of Minié offered a solution to that problem. (Minié is properly pronounced min-YAY, but Americans pronounced the name as “Minnie.”)

The British War Ministry was sufficiently impressed with the design to pay Minié a royalty of 20,000 pounds in 1852 to use it for British weapons. (This ignited a legal war between Greener and the British government, which finally awarded him the relative pittance of 1,000 pounds in recognition of his earlier work.)

When the Crimean War erupted between Russia on one side and the British and French on the other, the two western European nations demonstrated the effectiveness of their new weapons against the Russians’ smoothbore muskets. The London Times called the Minié “the king of weapons” that swept through the ranks of the czar’s soldiers “like the hand of the Destroying Angel.”

The Minié ball in the American Civil War

The United States had observers present during the 1853–1855 Crimean War, including the future commander of the Army of the Potomac, George B. McClellan. The Minié ball came to America, where it was improved on by James Burton, an armorer at the U.S. Arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). This hollow-based design could be mass-produced cheaply. Burton’s version of the new ammunition, along with the rifled musket for firing it, was adopted for use by the U.S. Army by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. Two different-size Minié balls were used: The Harpers Ferry rifle fired a .69 caliber round, while the Springfield design used .58 caliber.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, most state arsenals contained smoothbore muskets, and these were used extensively by both sides out of necessity. As the war progressed, smoothbores were phased out on both sides, replaced with rifled muskets, although the earlier weapons never totally disappeared from combat. The factories of the North were able to spit out the new muskets at a phenomenal rate compared with the less-industrialized South; in large measure, the North’s production capacity was due to mass-production techniques created by Eli Whitney, famed as the inventor of the cotton gin.

Rifled Muskets Compared with Smoothbores

The smoothbore had an effective range of 50 yards and an extended range of 200 yards. The rifled musket increased the lethality of ranged combat by providing an effective range of 300 yards, with an extended range of a half-mile. No longer could artillery crews set up just outside musket range to deliver devastating grapeshot or canister fire, as they had done during the Napoleonic Wars, because the rifled musket could easily pick off those crews if they were within the 300 yard-range of canister. (The development of conical-shaped shells also began a revolution in artillery as ammunition like the Parrott and James shells allowed for true rifling in cannon, giving the guns longer range and greater accuracy.)

A smoothbore’s load was a solid ball that rattled its way down the barrel when it was fired; judging what angle it was going to be traveling when it left the muzzle was difficult, virtually impossible under the rapid-fire conditions of combat. The soft-lead Minié ball, as noted above, expanded to fit the rifling of the barrel, giving it greater accuracy. At extremely close ranges, however, the smoothbore could be loaded with “buck and ball,” the 69-caliber ball and two smaller ones (“buckshot”), so that every shot sent three bullets spinning toward the enemy. Since troops armed with rifled muskets could stand off and fire from a greater distance, this smoothbore advantage only occurred during close-quarters fighting.

Increased musketry range caused a revolution in warfare: no longer could an attacker advance to charge range, suffer a volley or two from the defenders, and then attack with bayonets. The new weapons allowed defenders to inflict heavy casualties on the attackers as they advanced into charge range. Warfare had clearly tilted in favor of the defender.

While firepower had increased, communications hadn’t. The use of flags, bugles and drums to convey information still demanded keeping men close together for command control. This, and the traditional success of bayonet charges that still influenced many commanders, forced troops to continue to fight in closely packed formations that presented opponents armed with rifled muskets large targets.

Wounds Caused by Minié Balls

The soft lead that allowed Minié balls to expand within the rifle barrel also caused them to flatten out and/or splinter when they hit a human target. A smoothbore’s solid shot could break bones and tear through tissue, but soft lead bullets shattered bone and ripped tissue. Overworked Civil War surgeons often had to amputate limbs wounded by Minié balls. Adding to the damage, some soldiers notched their bullets to ensure they would spread out when they hit their target. In the 1870s, doctors urged an international ban on soft-lead bullets, saying they caused the same sort of damage as explosive bullets.

End of the Minié ball

The reign of the “king of weapons” did not last long. During the course of the Civil War, breechloading weapons and repeaters proved they could provide a much higher rate of fire than the rifled musket (their conical bullets with attached cartridges evolved from the Minié ball). Prussia demonstrated to European armies the impact of more rapid-fire on the battlefield when its “needle gun” breechloaders badly outclassed Austrian weapons during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. The era of ramming powder and a Minié ball down a barrel from the muzzle lasted less than a quarter of a century, but during that time, the new conical bullet and the rifled musket had shown the need for armies to develop new tactics that recognized the increased strength of defenders and the slaughter awaiting troops packed into tight linear battle formations. Tragically, that lesson wouldn’t take hold until after the carnage of World War I, 1914–1918.