Of the many battles the U.S. fought in the Vietnam War none hurt more than the 1965 battle in the Ia Drang Valley and the 1968 Tet Offensive. The outcome of those clashes and hundreds of smaller ones were not the clear-cut, decisive victories that senior American commanders expected.

That’s because they didn’t think the “primitive” enemy was shrewd enough and sophisticated enough to intercept radio communications, then use that information against U.S. troops.

When it was conclusively proved that the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong had those capabilities, military intelligence agencies briefed Gen. Creighton Abrams, the head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in early 1970.

He responded: “This is terrible. They are reading our mail, and it has to stop! Get the word out to every division and corps commander.”

It Shouldn’t Have Been A Surprise

The enemy radio intercepts shouldn’t have been a surprise. There had been warning signals for years. In the late 1950s the Army directed its Electronics Command at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, to develop a new “family” of single-channel tactical field radios to replace the obsolete inventory of World War II and Korean War field radio equipment still in use.

At the same time the Defense Department directed the National Security Agency to concurrently develop and field “communications security equipment,” to encrypt all tactical voice and data radio equipment developed by the services.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

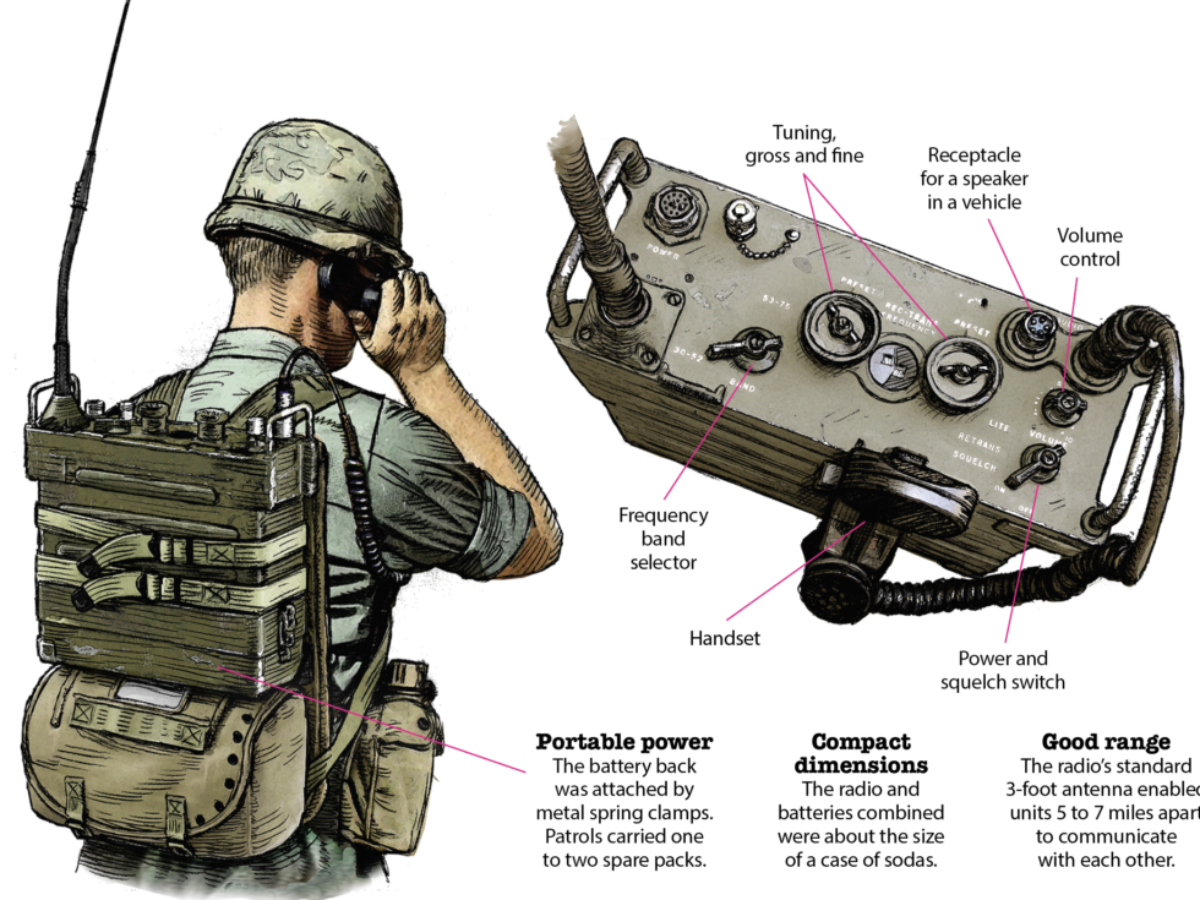

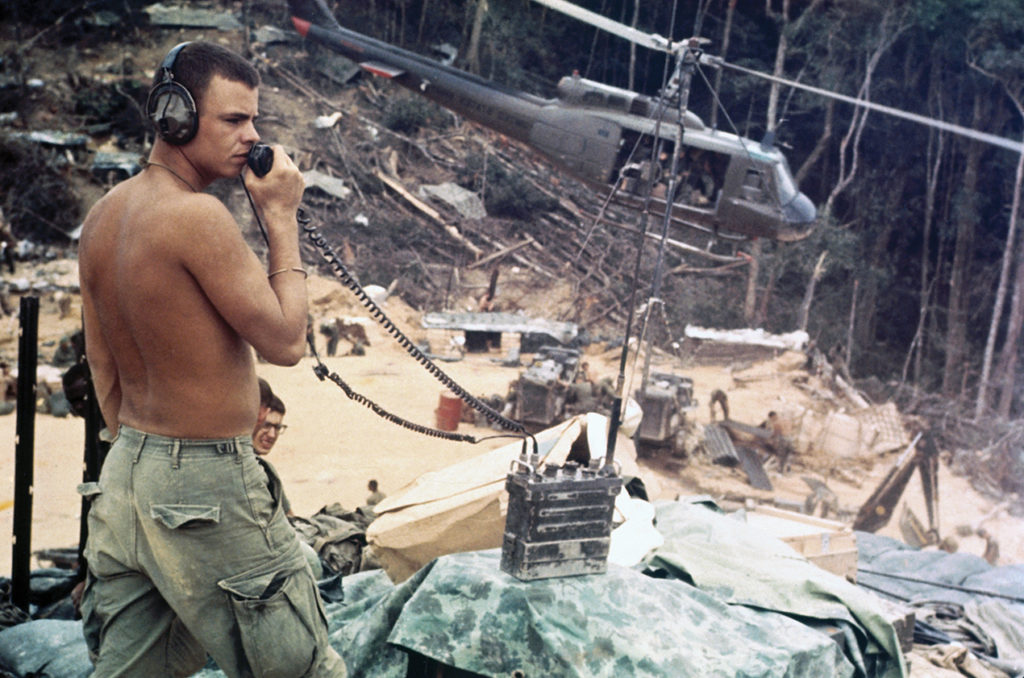

The result was a series of Army and joint services security regulations and directives incorporated into the equipment specifications for new Army single-channel combat network radios. The Army built a mostly transistorized vehicular mounted 50-watt radio (VRC-46), a toughened 1.5-watt manpack radio (PRC-25) and some hand-held, low-power transmitters and receivers (PRT-4, PRR-9) intended to replace the old walkie-talkie at the squad level.

Simultaneously, the NSA developed “narrow band secure voice equipment,” or NESTOR, to secure radios produced by the Electronics Command. Unfortunately, there were problems in the design, integration and production of this security equipment. Both technical and tactical adjustments had to be made to meet the Army’s fielding schedule because military operations in Vietnam were ramping up.

The communications security requirements for the PRT-4/PRR-9 radios were removed since the NSA could not come up with a small enough design for the hand-held and helmet-mounted radios. The elimination of the security requirement was justified tactically. The hand-held radios were intended for squad and platoon communications, and thus the radio’s power level was very low and the communications distance was very short.

The Vietnam ramp-up was bad news for security systems in the PRC-25. The basic radio met all of its specifications, but a PRC-25 manpack with NESTOR security equipment was far behind the basic radio in development.

With the fight in Vietnam intensifying, the Army decided to field the basic manpack radio without a communications security capability and wait for the NESTOR security hardware to become available. The Army planned to withdraw the PRC-25 from service when the NSA completed its NESTOR development and deploy an upgraded radio, identified as the PRC-77, with the proper communications security equipment.

Fortunately, the vehicle part of the family had very few issues and essentially met all technical, tactical and communications security requirements early in the troop buildup. Ditto for the aircraft version.

Unfortunately, the unsecured manpack radio would become the “workhorse” of combat communications because the preponderance of the ground fighting was done by infantry troops, including airborne and helicopter airmobile units.

The vehicle VRC-12/manpack PRC-25 family of combat network radios was a great step forward in tactical radio communications. The systems were extremely easy to install, operate and maintain in combat units. All the operator had to do was pick a radio frequency, a transmitter power level and one of two selectable noise reduction modes, then hook up an antenna and a handset, and he was operational.

Recommended for you

A Blessing And A Curse

That turned out to be both a blessing and a curse. Since the radios were so simple the Signal Corps changed Army doctrine and had the equipment designated as “user owned operated and maintained.” That meant radio telephone operators with fighting units in the field were no longer Signal Corps personnel but rather combat arms soldiers (infantry, artillery, armor).

With that change, officers and noncommissioned officers were taught how to operate the radios during basic and advanced individual training at combat arms training centers. The training received by officers and NCOs was barely above that of the unit RTOs (who mostly learned on the job), even though higher-level commanders still held them responsible for all combat communications.

In a glaring deficiency, the training failed to impress upon the officers and NCOs the critical role of proper antenna selection and operating frequency in radio system performance, which often resulted in unnecessary communications failures at critical moments on the battlefield.

Because the initial manpack radios had no communications security capability, the NSA substituted paper-based RTO procedures to assure broadcast security over combat radio networks. They included changing station call signs and network radio frequencies on a periodic paper-based schedule and the use of one-time operational codes (a random letter group substituted for a common military phrase) and “authentication tables” (enabling operators to identify valid stations in their radio networks). The NSA delivered pallet loads of Signal Operating Instructions, operations codes and authentication tables to Vietnam and all other commands worldwide very frequently.

The Call Sign Problem

The NSA-generated paper procedures, however, were cumbersome, complicated and easily lost. Units, particularly at division level and below, invented their own code systems (often based on distances from easily identified landmarks on military maps), seldom changed radio frequencies or station call signs and never assigned new code words to places like firebases, landing zones, base camps, command centers, medical facilities and other important locations. Key individuals, such as commanders, were given “sexy” code names that sounded super over the radio but were easily identified by enemy forces listening to radio transmissions.

Key individuals were given “sexy” code names that sounded super but were easily identified by enemy forces.

Each division had an attached field company from the Army Security Agency that monitored radio communications and reported violations to unit commanders, but they were mostly ignored by commanders, and signal officers who grew up watching World War II movies on TV and thought their homemade communications security systems were great. Throughout the war, many key units never addressed their radio security problems until battlefield losses forced them to do so.

The attitude of commanders at all levels was expressed by Col. Sidney Berry, a brigade commander in the 1st Infantry Division, who stated: “It simplifies communications for units and individuals to keep the same radio frequency and particularly call signs. Frequent changes of call signs confuses friendly forces more effectively then enemy actions.” Unfortunately, Berry was very wrong.

Despite numerous warnings from the NSA, ASA and other intelligence sources that their radio networks were being intercepted and exploited, both U.S. Army Vietnam, a logistics and support organization, and MACV refused to believe the warnings or take any action.

Maj. Gen. Harry Kinnard, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), received a report of 11,000 communications violations during pre-deployment training monitored by the ASA prior to the division’s departure for Vietnam.

Kinnard dismissively said: “Even if the VC/NVA could intercept our radio communications and understand English well enough to know what a message meant, our actions are so immediate, and our movements so rapid that they would never be able to exploit any information ‘gleaned’ from a radio intercept.” That comment was typical.

Denial of the enemy’s radio intercept capabilities continued from the first large deployments in 1965 until the morning of Dec. 20, 1969. A scout from the 1st Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, discovered a long wire antenna on the old Michelin rubber plantation northwest of Saigon. The antenna was connected to a concealed underground bunker complex packed with radio equipment.

The bunker was the operations center for an NVA/VC platoon later identified as Alpha-3, part of the NVA’s 47th Tactical Reconnaissance Battalion. After a short fight, 12 Alpha-3 personnel were captured along with all their equipment, training material and, most important, their logbooks.

Yes, Communist Intel Operatives Understood English

The logbooks were written in perfect English (the language our senior commanders doubted the enemy could understand). This proved beyond a doubt that the communist intercept and exploitation effort been underway since the arrival of U.S. military advisers in the early 1960s.

Writings in the logbooks revealed that the radio intercept personnel understood the exact meaning of American voice conversations. The 47th Reconnaissance Battalion personnel easily deciphered locally generated unit codes and took advantage of infrequent call sign changes and radio frequency adjustments.

Of particular interest, according to the training manuals, were communications involving forward air controllers (spotter planes that directed airstrikes), artillery forward observers (artillerymen embedded in infantry units to adjust the fire of artillery batteries), command and control leaders, and the civilian press.

The press was a great source of immediate operational information throughout the war, which could have easily been prevented. Press reports were not censored in Vietnam, but there could have been a time delay until the operation was completed.

The captured material confirmed the ASA/NSA warnings to senior commanders. Alpha-3 logs showed that from the beginning of the war North Vietnamese personnel were intercepting, analyzing and tactically reacting to news broadcasts and information disclosed over military radios, such as artillery targets, artillery harassment and fire schedules, ambush site locations, casualty reports, airstrike warnings, troop positions, radio call sign and frequency changes, unit status reports, and unit plans and operations.

The logs also revealed that idle radio operator chatter was a lucrative source of operational information.

The documents also included transcripts of American conversations that were copied down verbatim even though the U.S. personnel transmitting them assumed they would be incomprehensible to enemy listeners. Next to the text, enemy analysts wrote the transmission call sign, the unit, identity of the sender, and the position of senders and their locations, along with the analysis of what the transmission meant.

Predicting American Moves

There is evidence that the 47th Reconnaissance Battalion’s personnel were educated enough to understand the tone and content of intercepted radio traffic as well as the tactics and procedures, so that they could actually predict individual unit actions.

Typical entries would say (written in English): “This is a Company Commander (call sign) telling his Battalion Commander (call sign) that there is an ambush site at (coordinates) to be occupied tonight. This unit is probably part of (U.S. unit) known to be operating in this area.”

There were hundreds of similar entries in the captured logbooks. Of course, after reading this type of a log entry one wonders who ambushed whom that night.

The 47th Reconnaissance Battalion training materials went into great detail and plainly stated that American units didn’t change call signs or radio frequencies very often. And when they did, some elements of the old network structure were often retained so that confused operators who lost contact could transmit the new network information over the air. Knowing this, the 47th could adapt to the new network structures even before they were fully implemented.

The communist training material also explained that radio operators who were battalion- and brigade-level officers and senior NCOs were often prone to long transmissions that invariably led to disclosure of important operational information.

If this was not shocking enough, the training materials showed in detail how extracted information was used against specific U.S. units in their operational area.

The 47th Reconnaissance Battalion’s targets were the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the 1st Infantry Division, the 25th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). Other communist reconnaissance battalions no doubt were targeting American units in other operational areas.

The NVA and VC managed to profile U.S. units in their area to the degree that they knew not only the U.S. unit opposing them, but also the methods of navigation being used (particularly if it was a landmark-based code) and the weapons, equipment and modes of transportation. They were impressed by the UH-1 “Huey” helicopter and the M113 armored personnel carrier, but not the V-100 armored car used by military police for base and road patrols. The M151 jeep also did not impress them.

Simple Enemy Technology

Alpha-3’s actual radio intercept hardware wasn’t particularly sophisticated. It was certainly not the product of some super-secret Chinese or Soviet communications laboratory. It consisted mostly of PRC-25 radios captured from American units and their Vietnamese partners or purchased through a third party that acquired them in a U.S. foreign military sales program.

Obviously, those radios were able to receive U.S. radio traffic since they were American radios. To supplement the captured U.S. radios, Alpha-3 had several Chinese R-139 radio receivers and Sony and Panasonic commercial radios modified in the field to operate in the U.S. tactical radio frequency band.

Alpha-3 must have had some very good radio engineers in its ranks, since they not only were able to modify the commercial equipment but also engineered a way around the critical shortage of BA-4386 radio batteries needed by U.S. forces. Alpha-3 engineers produced the 12 volts direct current required to operate the PRC-25 receiver by soldering together common flashlight batteries.

The enemy engineers also designed, fabricated and deployed radio antennas that were much more efficient than the standard antennas that came with the PRC-25. This allowed them to stand long distances away from U.S. units, where it was safer. Additionally, the antennas were much more concealable, a critical factor for clandestine intercept operations.

After the capture of Alpha-3 in 1969, the U.S. lack of electronic communications security could no longer be denied. Training levels increased, but never to the point where 100 percent of U.S. radio networks were secure. The NSA did manage to get manpack NESTOR equipment to combat units to secure communications.

However, the unit RTO had to then carry the radio and the NESTOR, whose combined weight came to 54 pounds, plus his weapon and personal gear, plus in most units spare batteries and maybe also other communications equipment like flares and smoke grenades. Quite a load for one soldier, so the NESTOR invariably got left behind and the security situation did not change.

This far-from-ideal situation lasted until 1973 when all U.S. forces were withdrawn from Vietnam. Summing it all up, Lt. Gen. Charles Myer, former commander of the 1st Signal Brigade, the largest Signal Corps unit in Vietnam, said: “All users were more or less aware [after 1969] of their vulnerabilities to enemy intercept, analysis, and decoding and the need for authentication and encoding. The gap between this knowledge and actual practice [in combat units] was immense and in Vietnam it was an insurmountable problem.”

Eavesdropping at Ia Drang

There are several painful examples of the impact that intercepted radio signals had on U.S. operations, but perhaps the most notable occurred in the first major encounter between American forces and the North Vietnamese. In mid-November 1965, 500 troopers in UH-1 “Huey” helicopters of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), under the command of Lt. Col. Hal Moore, were dropped into a small landing zone in the Ia Drang Valley in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The landing zone had been named LZ X-Ray. It was common practice to give landing zones identifiers and call signs, most of which didn’t change.

X-Ray was only 15 miles from Plei Me, the base camp of Moore’s parent 3rd Brigade and his source of combat support, but Plei Me was still well outside the reach of the PRC-25-manpack radio (3-7 miles) that was the combat communications heart of the 1st Battalion.

Another problem: X-Ray was near the Chu Pong massif (mountain) dominating the valley at an altitude that enabled U.S. communications during the fight to be easily monitored by both sides. The 1st Cavalry Division did not know that Chu Pong was occupied by a multibattalion North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong force that included a radio-intercept reconnaissance organization.

Moore did not know that an Army Security Agency detachment at Ple Me would monitor more than 28,000 radio transmissions during the three-day battle that killed 234 Americans and wounded hundreds more in three 1st Cav battalions—Moore’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry; the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry; and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment.

The enemy monitoring effort revealed the location of LZ X-Ray and the fact that there were only enough helicopters available to lift one company of Moore’s battalion into the landing zone at a time. With that intelligence, the enemy force attacked the first troop lift immediately after landing, isolating platoon-size units and causing heavy casualties. As the rest of the battalion flew in piecemeal, each lift was attacked in turn, resulting in the U.S. force being surrounded and nearly wiped out.

Adding to the battalion’s troubles, the radio telephone operators, poorly trained at combat arms schools, along with many officers and senior noncommissioned officers, were disclosing all sorts of operational information that the enemy intercepted. The offline, paper-based system of codes and authentication tables proved too time consuming to be useful and was abandoned.

The only thing that saved the 1st Battalion from destruction was artillery support from surrounding firebases, close-air support and the grit and determination of Moore’s troopers. Ironically, the artillery forward observers and the forward air controllers were using virtually the same radio equipment as the infantry, but they were better trained and used the equipment well.

Thanks to the overwhelming ground and air support and reinforcements from the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, U.S. forces finally beat back the NVA/VC. They secured LZ X-Ray, though not much more than that. Moore and the battered 1st Battalion were lifted out from X-Ray, but the battle was not over.

The 1st Cavalry Division instructed the remaining battalions (over the intercepted nonsecure radio, of course) to withdraw in column to LZ Columbus a few miles away, where the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, would be lifted out. The last battalion, the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Cavalry, would then move a few more miles to LZ Albany, where it would be extracted. All instructions, such as unit order of march, landing zone names/locations, security plans, airlift plans, artillery plans, etc. were again broadcast in the clear and again intercepted by the enemy reconnaissance unit.

The NVA/VC allowed the lift at Columbus to proceed unmolested, thus cutting the U.S. force in half, and then hit the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, on the trail to LZ Albany so hard that it, along with the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, was out of combat for months to come. —David M. Fiedler

Lessons Learned and Not Learned

- Good communications security can save the lives of American troops, and bad communications security will cost lives. No one knows how many lives were lost in Vietnam due to poor communications security, but the number is not small and certainly far exceeds the much-talked-about losses due to “friendly fire” and noncombat related deaths.

- The U.S. learned the hard way that American forces needed a new family of combat network radios with integrated equipment security, and in the 1980s and beyond they got them.

- Unit commanders need better communications security training even today. In Iraq and Afghanistan there were many instances of commanders permitting the use of troop-purchased nonsecure commercial hand-held radios for combat operations.

- The use of individual identifying call signs is still with us and needs to be stamped out. Who among us cannot identify Maverick and Goose from Top Gun? Who doesn’t know what POTUS means? It has to stop.

- Press conferences need to be carefully thought out even today. In Vietnam, the logbooks of the enemy’s Alpha-3 reconnaissance unit make many references to information such as unit deployments, unit strengths and ongoing operations revealed by monitoring U.S. radio and television commercial broadcasts. President Lyndon B. Johnson himself disclosed on national TV that “today I have ordered the Air Mobile Division [1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile)] to Vietnam.”

This article appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.