Passengers on this “railroad” never forgot their life-or-death journey from bondage.

Arnold Gragston struggled against the current of the Ohio River and his own terror the first night he helped a slave escape to freedom. With a frightened young girl as his passenger, he rowed his boat toward a lighted house on the north side of the river. Gragston, a slave himself in Kentucky, understood all too well the risks he was running. “I didn’t have no idea of ever gettin’ mixed up in any sort of business like that until one special night,” he remembered years later. “I hadn’t even thought about rowing across the river myself.”

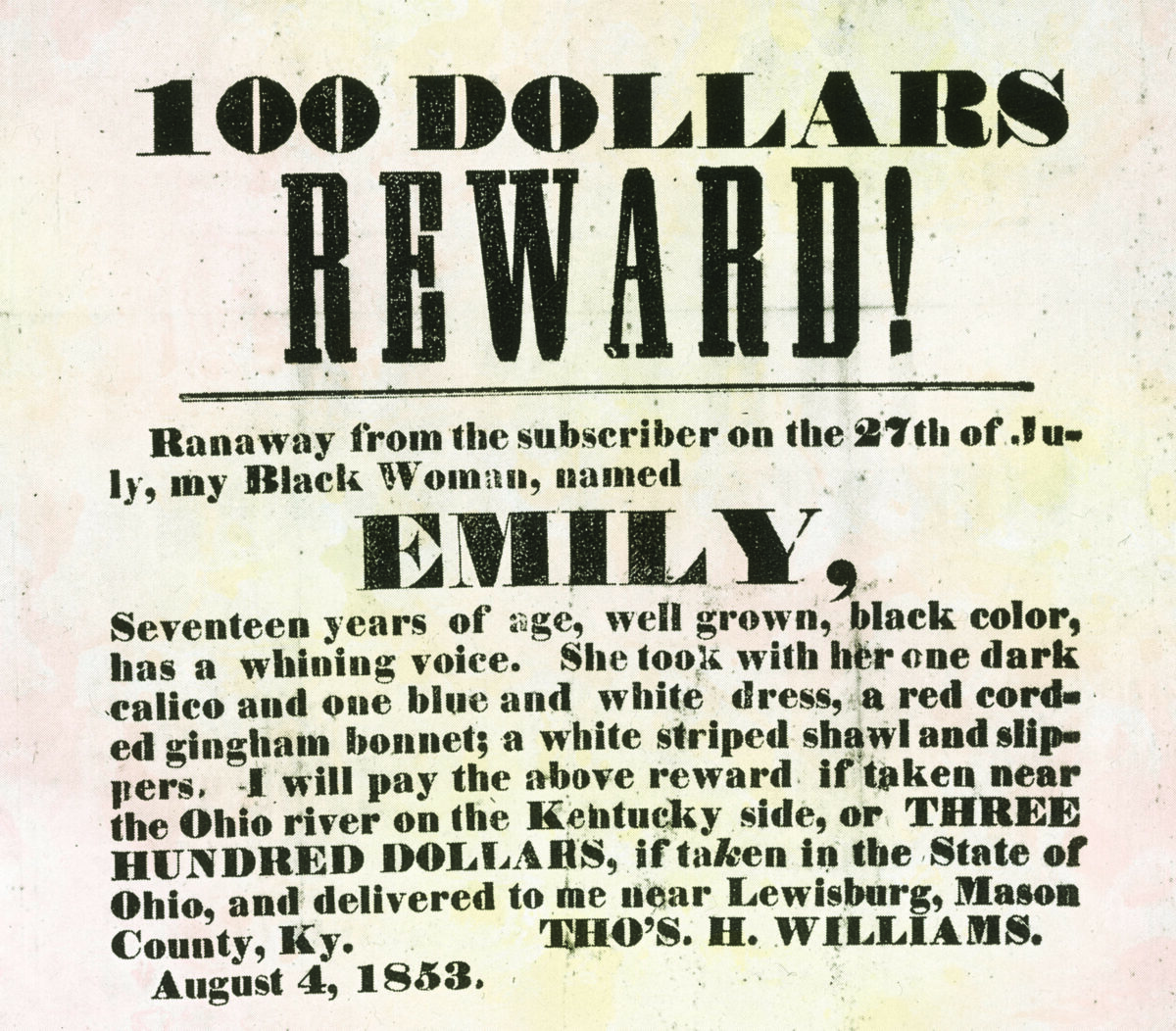

Slaves had been making their way north to freedom since the late 18th century. But as the division between slave and free states hardened in the first half of the 19th century, abolitionists and their sympathizers developed a more methodical approach to assisting runaways. By the early 1840s, this network of safe houses, escape routes and “conductors” became known as the “Underground Railroad.” Consequently, a cottage industry of bounty hunters chasing escaped slaves sprang to life as lines of the railroad operated across the North—from the big cities of the East to the little farming towns of the Midwest. Above all else, the system depended on the courage and resourcefulness of African Americans who knew better than anyone the pain of slavery and the dangers involved in trying to escape.

In a 1937 interview with the Federal Writers’ Project, Gragston recalled that his introduction to the Underground Railroad had occurred only a day before his hazardous trek, when he was visiting a nearby house. The elderly woman who lived there approached him with an extraordinary request: “She had a real pretty girl there who wanted to go across the river, and would I take her?”

The dangers, as Gragston well knew, were great. His master, a local Know-Nothing politician named Jack Tabb, alternated between benevolence and brutality in the treatment of his slaves. Gragston remembered that Tabb designated one slave to teach others how to read, write and do basic math. “But sometimes when he would send for us and [if] we would be a long time comin’, he would ask us where we had been. If we told him we had been learnin’ to read, he would near beat the daylights out of us—after getting somebody to teach us.”

Gragston suspected such arbitrary displays of cruelty were meant to impress his master’s white neighbors and considered Tabb “a pretty good man. He used to beat us, sure; but not nearly so much as others did, some of his own kin people, even.”

Tabb seemed especially fond of Gragston and “let me go all about,” but Gragston realized what would happen if he were caught helping a slave escape to freedom—Tabb would probably shoot him or whip him with a rawhide strap. “But then I saw the girl, and she was such a pretty little thing, brown-skinned and kinda rosy, and lookin’ as scared as I was feelin’,” he said. Her plaintive countenance won out, and “it wasn’t long before I was listenin’ to the old woman tell me when to take her and where to leave her on the other side.”

While agreeing to make the perilous journey, Gragston insisted on delaying until the next night. The following day, images of what Tabb might do wrestled in Gragston’s mind with the memory of the sad-looking fugitive. But when the time came, Gragston resolved to proceed. “Me and Mr. Tabb lost, and as soon as [dusk] settled that night, I was at the old lady’s house.

“I don’t know how I ever rowed the boat across the river,” Gragston remembered. “The current was strong and I was trembling. I couldn’t see a thing there in the dark, but I felt that girl’s eyes.”

Gragston was certain the effort would end badly. He assumed his destination would be like his home in Kentucky, filled “with slaves and masters, overseers and rawhides.” Even so, he continued to row toward the “tall light” the old woman had told him to look for. “I don’t know whether it seemed like a long time or a short time,” he recalled. “I know it was a long time, rowing there in the cold and worryin’.” When he reached the other side, two men suddenly appeared and grabbed Gragston’s passenger—and his sense of dread escalated into horror. “I started tremblin’ all over again, and prayin’,” he said. “Then one of the men took my arm and I just felt down inside of me that the Lord had got ready for me.” To Gragston’s astonishment and relief, however, the man simply asked Gragston if he was hungry. “If he hadn’t been holding me, I think I would have fell backward into the river.”

Gragston had arrived at the Underground Railroad station in Brown County, Ohio, operated by abolitionist John Rankin. A Presbyterian minister, Rankin published an anti-slavery tract in 1826 and later founded the American Anti-Slavery Society. Rankin and his neighbors in Ripley provided shelter and safety for slaves fleeing bondage. Over the years, they helped thousands of slaves find their way to freedom—and Gragston, by his own estimate, assisted “way more than a hundred” and possibly as many as 300.

He eventually made three to four river crossings a month, sometimes “with two or three people, sometimes a whole boatload.” Gragston remembered the journeys more vividly than the men and women he took to freedom. “What did my passengers look like? I can’t tell you any more about it than you can, and you weren’t there,” he told his interviewer. “After that first girl—no, I never did see her again—I never saw my passengers.” Gragston said he would meet runaways in the moonless night or in a darkened house. “The only way I knew who they were was to ask them, ‘what you say?’ And they would answer, ‘Menare.’” Gragston believed the word came from the Bible but was unsure of its origin or meaning. Nevertheless, it served its purpose. “I only know that it was the password I used, and all of them that I took over told it to me before I took them.”

The dangers increased as Gragston continued his work. After returning to Kentucky one night from a river crossing with 12 fugitives, he realized he had been discovered. The time had come for Gragston and his wife to make the journey themsleves. “It looked like we had to go almost to China to get across that river,” he remembered. “But finally, I pulled up by the lighthouse, and went on to my freedom—just a few months before all of the slaves got theirs.”

The work of the Underground Railroad involved a network of white abolitionists, dedicated slaves like Gragston and free African Americans such as William Still of Philadelphia. The youngest of 18 children, Still was born in 1821, moved to Philadelphia in the mid-1840s and went to work for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society as a mail clerk and janitor. He rose to prominence in the city’s burgeoning abolitionist movement and served as chairman of the General Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia. Still was closely involved in the planning, coordinating and communicating required to keep the Underground Railroad active in the mid-Atlantic region. He became one of the most prominent African Americans involved in the long campaign to shelter and protect runaways.

In The Underground Rail Road, a remarkable book published in 1872, Still recounted the stories of escaped slaves whose experiences were characterized by courage, resourcefulness, pain at forced partings from family members and, above all, a desperate longing for freedom. For Still, aiding runaway slaves—and helping to keep families intact—was a deeply personal calling. Decades earlier, his parents had escaped slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. William’s father, Levin, managed to buy his freedom after declaring as a young man that “I will die before I submit to the yoke.”

William’s mother, Sydney, remained in bondage, but she fled with her four children to Greenwich, N.J., only to be seized by slave-hunters. Sydney and her family were returned to Maryland, but she escaped a second time to New Jersey. She changed her name to Charity to avoid detection and rejoined her husband, but their reunion was tarnished by the knowledge that she was forced to leave two boys behind. Her angry former owner promptly sold them to an Alabama slaveholder. William Still would eventually be united with one of his enslaved brothers, Peter, who escaped to freedom in the North—a miraculous event that after the war inspired William to compile his history, hoping it would promote similar reunions.

The work of the Underground Railroad became the focal point of pro- and anti-slavery agitation after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Part of that year’s grand legislative compromise aimed at halting the slide toward civil war, the law required federal marshals to capture escaped slaves in Northern free states and denied jury trials to anyone imprisoned under the act. Abolitionists and supporters of slavery—each for their own reasons—tended to exaggerate the extent of the railroad’s operations, historian James McPherson observes, but there was no denying its effectiveness. As the decade progressed, the Fugitive Slave Act gave the work of the Underground Railroad new urgency.

Perhaps no one embodied the hunger for freedom more completely than John Henry Hill. A father and “young man of steady habits,” the 6-foot, 25-year-old carpenter was, in Still’s words, “an ardent lover of Liberty” who dramatically demonstrated his passion on January 1, 1853. After recovering from the shock of being told by his owner that he was to be sold at auction in Richmond, Hill arrived at the site of the public sale, where he mounted a desperate struggle to escape. Employing fists, feet and a knife, he turned away four or five would-be captors and bolted from the auction house. He hid from his baffled pursuers in the kitchen of a nearby merchant until he decided he wanted to go to Petersburg, Va., where his free wife and two children lived.

He stayed in Petersburg as long as he dared, leaving only when informed of a plot to capture him. Hill returned to his kitchen hideout in Richmond before learning that Still’s Vigilance Committee had arranged—at the considerable cost of $125—for him to have a private room on a steamship leaving Norfolk for Philadelphia. Four days after departing Richmond on foot, he arrived in Norfolk and boarded ship—more than nine months after escaping from the auction. “My Conductor was very much Excited,” Hill later wrote, “but I felt as Composed as I do at this moment, for I had started…that morning for Liberty or for Death providing myself with a Brace of Pistels.”

On October 4, Hill wrote Still to inform him that he had arrived safely in Toronto and found work. But other matters preoccupied him. “Mr. Still, I have been looking and looking for my friends for several days, but have not seen nor heard of them. I hope and trust in the Lord Almighty that all things are well with them. My dear sir I could feel so much better sattisfied if I could hear from my wife.”

But the Christmas season of 1853 brought good news. “It affords me a good deel of Pleasure to say that my wife and the Children have arrived safe in this City,” Hill wrote on December 29. Although she lost all her money in transit—$35—the family reunion proved deeply moving. “We saw each other once again after so long, an Abstance, you may know what sort of metting it was, joyful times of corst.”

During the next six years, Hill frequently wrote Still, reflecting on his experiences in Canada, the situation in the United States—and sometimes passing on sad family news. On September 14, 1854, Hill wrote of the death of his young son, Louis Henry, and his wife’s heartache at the boy’s passing. In another letter, Hill fretted about the fate of his uncle, Hezekiah, who went into hiding after his escape and ultimately fled to freedom after 13 months. Hill’s letters are replete with concern for escaped slaves and the volunteer “captains” of the Underground Railroad who risked imprisonment or death to assist runaways. Still acknowledged Hill’s spelling lapses but praised his correspondence as exemplifying the “strong love and attachment” freed slaves felt for relatives still in bondage.

Despite enormous difficulties, some families managed to escape to freedom intact.

Ann Maria Jackson, trapped in slavery in Delaware, made up her mind to flee north with her seven children when she learned alarming news of her owner’s plans. “This Fall he said he was going to take four of my oldest children and two other servants to Vicksburg,” she confided to Still. “I just happened to hear of this news in time. My master was wanting to keep me in the dark about taking them, for fear that something might happen.”

Those fears were well-founded. Upon learning of his planned departure for Mississippi, quick-thinking Jackson gathered her children and headed for Pennsylvania. The presence of slave-hunting spies along the state line complicated the family’s escape, but on November 21 a volunteer reported to Still that Jackson and her children, ranging in age from 3 to 16, were spotted across the state line in Chester County. From Pennsylvania, the family continued north into Canada. The 40 or so years Jackson had spent in slavery were at an end.

“I am happy to inform you that Mrs. Jackson and her interesting family of seven children arrived safe and in good health and spirits at my house in St. Catharines, on Saturday evening last,” Hiram Wilson wrote to Still from Canada on November 30. “With sincere pleasure I provided for them comfortable quarters till this morning, when they left for Toronto.”

Caroline Hammond’s family faced different challenges. Born in 1844, Hammond lived on the Anne Arundel County, Md., plantation of Thomas Davidson. Hammond’s mother was a house slave and her father, George Berry, “a free colored man of Annapolis.”

Davidson, she remembered, entertained on a lavish scale, and her mother was in charge of the meals. “Mrs. Davidson’s dishes were considered the finest, and to receive an invitation from the Davidsons meant that you would enjoy Maryland’s finest terrapin and chicken besides the best wine and champagne on the market.” Thomas Davidson, Hammond recalled, treated his slaves “with every consideration he could, with the exception of freeing them.”

Mrs. Davidson, however, was a different story. She “was hard on all the slaves, whenever she had the opportunity, driving them at full speed when working, giving different food of a coarser grade and not much of it.” Her hostility would soon evolve into something more sinister.

Hammond’s father had arranged with Thomas Davidson to buy his family’s freedom for $700 over the course of three years. Working as a carpenter, Berry made periodic partial payments to Thomas Davidson and was within $40 of completing the transaction when the slaveowner died in a hunting accident. Mrs. Davidson assumed control of the farm and the slaves, Hammond remembered—and refused to complete the transaction Berry had arranged with her late husband. As a result, “mother and I were to remain in slavery.”

The resourceful Berry, however, was undeterred. Hammond recalled that her father bribed the Anne Arundel sheriff for permits allowing him to travel to Baltimore with his wife and child. “On arriving in Baltimore, mother, father and I went to a white family on Ross Street—now Druid Hill Avenue, where we were sheltered by the occupants, who were ardent supporters of the Underground Railroad.”

The family’s escape had not gone unnoticed. Hammond remembered that $50 rewards were offered for their capture—one by Mrs. Davidson and one by the Anne Arundel sheriff, perhaps to protect himself from criticism for the role he played in aiding their escape in the first place. To flee Maryland, Hammond and her family clambered into “a large covered wagon” operated by a Mr. Coleman, who delivered merchandise to the towns between Baltimore and Hanover, Pa.

“Mother and father and I were concealed in a large wagon drawn by six horses,” Hammond recalled. “On our way to Pennsylvania we never alighted on the ground in any community or close to any settlement, fearful of being apprehended by people who were always looking for rewards.”

Once they were in Pennsylvania, life for Caroline and her family got much easier. Her mother and father settled in Scranton, worked for the same household and earned $27.50 a month. Hammond attended school at a Quaker mission.

When the war ended, her family returned to Baltimore. Hammond completed the seventh grade and, just like her mother, became a cook.

As she recounted her experiences as a slave in a 1938 interview with the Federal Writers’ Project, Hammond looked back on a life of 94 years with justified pride and satisfaction.

“I can see well, have an excellent appetite, but my grandchildren will let me eat only certain things that they say the doctor ordered that I should eat. On Christmas Day 49 children and grandchildren and some great-grandchildren gave me a Christmas dinner and $100 for Christmas,” she declared. “I am happy with all the comforts of a poor person not dependent on anyone else for tomorrow.”

Not surprisingly, freedom produced the same bliss and relief for a number of Underground Railroad passengers.

Hill’s correspondence with Still is suffused with the escaped slave’s profound joy in his new life. Even as he mourned the loss of his son, Hill reflected on his contentment. “It is true that I have to work very hard for comfort,” he acknowledged in a letter to Still in 1854, but freedom more than compensated for his grief and hardship.

“I am Happy, Happy.”

Robert B. Mitchell is the author of Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver.