UNITED STATES NAVAL RESERVE Specialist Second Class Newton J. Jones stood 5 feet 9 3/4 inches tall. He had short-cropped brown hair, a prominent nose, and the pale complexion of his mother’s Swedish ancestors. In the summer of 1944, he was 36 years old, with laugh lines beginning to deepen around his slate-gray eyes.

But all that could be changed in an instant.

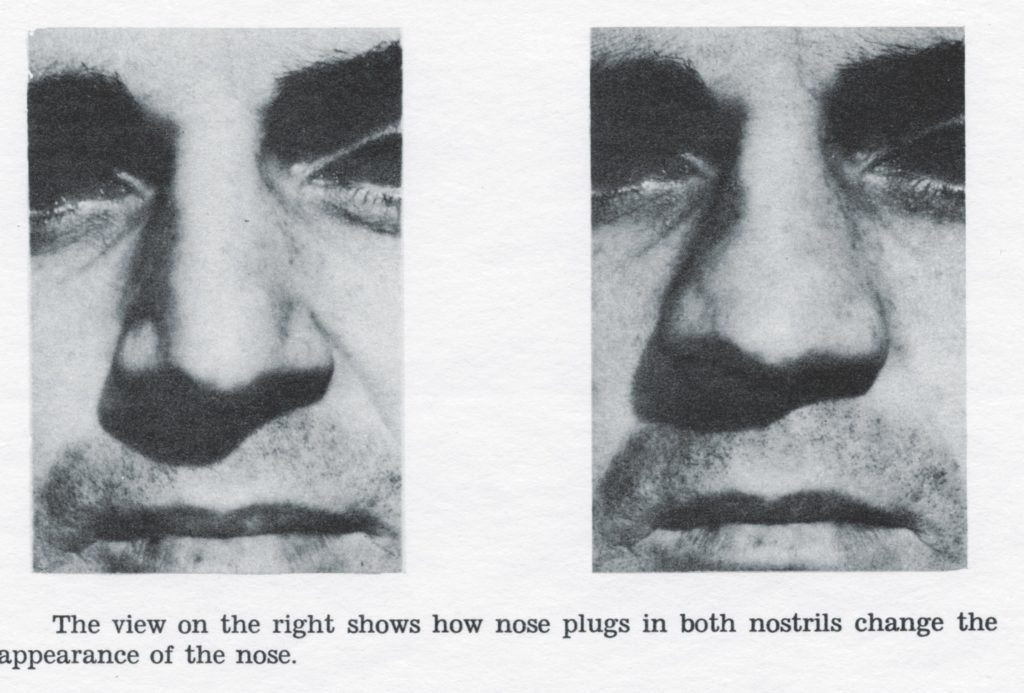

Jones knew that if he slumped his shoulders and wore his trousers low on his hips so that the fabric pooled at his ankles, he could shave several inches off his height. Allowing his jacket to hang open, its pockets stuffed with newspapers to weigh it down, would enhance the effect. Shoeblack painted on the collar and cuffs would make the garment appear soiled from nights spent sleeping rough, and some car grease stippled across his cheeks would mimic a days-old beard. His hair and eyebrows could be blackened with soot from inside a stovepipe; the same ash, mixed with rust scraped from a water heater vent, could be used to create the appearance of heavy bags beneath his eyes, gaunt cheeks, and a crooked nose, perhaps broken in a long-ago bar brawl. A small stone slipped into the heel of one of his socks would give him the stuttering step of an ailing man—and suddenly, Jones was no longer a hale American naval specialist on a secret assignment from the director of the Office of Strategic Services. He was a stooped and elderly tramp, easily overlooked on the streets of any city.

Jones’s ability to transform one person into someone else entirely was invaluable in Hollywood, where he had been an in-demand movie makeup man for more than a decade, but now he had been asked to take his talents into the operational theaters of World War II. Armed with only his makeup kit, Jones would teach the espionage agents of the OSS how to hide in plain sight. “If just one of the things you learn will save the neck of just one operator in this war—it is well worth all the effort we have put into it,” Jones told the spies he drilled on personal disguise in 1944 and 1945. “Remember—that man might be you.”

OSS DIRECTOR Bill Donovan wanted his agents everywhere. “Wild Bill,” as he was known, had convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to establish the intelligence organization in June 1942 with the promise of a new weapon for the war: information. “Strategy, without information upon which it can rely, is helpless,” Donovan warned the president. To obtain this valuable intelligence, he staffed the OSS with “men calculatingly reckless with disciplined daring.” The next challenge was inserting his spies behind enemy lines, a mission that would require the cooperation of America’s allies. Donovan had spent early December 1943 in testy negotiations with China’s intelligence chief, General Dai Li, for permission to send operatives into that country to surveil the encroaching Japanese forces. In late December, the director headed to Moscow in hopes of forging an alliance with the NKGB, the Soviet secret police. But there would be no bargaining for access to Germany.

The question of how to infiltrate the Reich was on the director’s mind as he hopscotched around the Mediterranean in the winter of 1944. There, Donovan heard stories of thousands from France who had been pressed into labor at factories in Germany. Could OSS agents pass as young French workers? “I directed that a study be made at once to determine if something might be done to instruct intelligence agents in the use of simple disguises,” Donovan informed his deputy.

The London branch of the OSS already had a props department to rival that of any movie studio. The Research and Development Division’s secret “Camouflage Shop” was located at 14 Mount Row in London’s upscale Mayfair neighborhood. By the time Newton Jones arrived in late summer 1944, printing presses clattered and sewing machines whirred, producing counterfeit documents and picture-perfect European clothing, some secured with hollow buttons for hiding contraband. Even among the closed-lipped agents of the Camouflage Shop, Jones and his mission were a cipher. “No information or advanced notice was given relative to his arrival,” complained one higher-up, and “he is reluctant to pass on any information to us.”

The mysterious Jones had been a member of the OSS’s Field Photographic Branch since 1942. The branch itself got its start in Hollywood in 1940 under the direction of John Ford. As in the credits of his Oscar-winning movies, Ford took top billing as commander of the Naval Reserve unit; cinematographers were his lieutenants; and grips, special-effects artists, and makeup men populated the lowlier ranks. In its earliest days, when the United States was still at peace, the reserve unit had mustered on a giant soundstage at 20th Century-Fox. The dimensions of a ship’s deck were taped out on the floor. The men learned—as every navy man must—to salute when coming onto the quarterdeck, but they drilled not with guns, but with Mitchell cameras and the film ends left over from Westerns and love stories. When the war came, “the cream of Hollywood motion picture technicians”—as Donovan said when he brought the naval unit into the OSS—aimed their lenses at coastlines and airports, trade routes and troop movements, and produced training videos. Jones had a decidedly unglamorous job in postproduction, adding title screens to the footage—until 1944, when Donovan’s disguise request arrived.

Lieutenant Ray Kellogg, the acting head of the Field Photographic Branch, had known Jones was the right man for the undertaking Donovan described. Jones had been in Hollywood since the arrival of the talkie. From his start as a blueprint boy for famed Paramount art director William Cameron Menzies in 1928, Jones had made his name as a makeup magician. When, in 1937, Jones transformed mezzo-soprano Gladys Swarthout into a 1920s Austrian beauty for Champagne Waltz, she told people she had the “bewildered feeling she is someone else every time she peers into a mirror.” Other subjects, though, were far less willing. After Jones wrestled Henry Fonda into pancake makeup in 1938’s I Met My Love Again, someone tattled to the papers about the star’s aversion to cosmetics. As one reporter described it, Fonda “practically has to be bound and gagged before a makeup man can get a dash of this or that on his face to kill a shadow in a close-up for some particular scene.”

The persuasive makeup man also had a knack for making something from nothing: Jones had carved soap into an army for the miniature sets used to create sweeping battle-scapes in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Crusades in 1935 and painted a Great Dane into the spitting image of a tiger for another film. After so many years in showbiz, Jones was “touched,” the OSS personnel department cautioned, “with some of the frenetic drive and tension of the industry,” and there was a “component of instability in this man.” But in a city under siege, tasked with rapidly training agents destined for enemy territory, those qualities would be more benefit than detriment.

JONES SPENT the month of September 1944 in London developing a curriculum on the basics of disguise, both quick changes with materials scavenged from one’s surroundings for eluding pursuit, and character changes with professional makeup for long-term undercover work. He would train both agents preparing for espionage missions and those who would teach these skills to others.

“It will not try the impossible: to turn them into skilled make up men in a few easy lessons,” Jones reminded his superiors. “All, however, should be able to learn enough basic rules and tricks on disguises to make the effort well worth while.” He would show pupils how to transform their clothing, change their posture and gait, and reshape their features. False mustaches would be a particular point of focus; Jones spent significant time locating a reliable source for the delicate, handcrafted prosthetics. Most importantly, though, he planned to instruct on human behavior. In his first lecture, he advised, “People as a whole, fortunately, are very unobservant. Put an accepted commonplace label on a man or a thing and most people never go any deeper. The surest way to hide is to be one of the crowd.”

Jones’s first two students were “Gene” and “Bob,” two agents whom he referred to in memos only by those code names. Gene and Bob were assigned to “Milwaukee Lookout,” a new outpost established in Luxembourg for the purpose of infiltrating Germany. He only needed a few hours with them on Friday, October 6, before putting their new skills to the test the following day. The men collected materials—rust, soot, and ashes—and together spent nine minutes giving Gene a “quick change.” With his arms akimbo, a coat gathered loosely in one crooked arm and a hat held in his hand at his other hip, his stance casual, his face bare and his smile wide, Gene was short with a solid build, an affable salesman. Moments later, wearing the hat and a pair of dark-rimmed glasses, a carefully trimmed mustache attached with spirit gum above a tight grimace, his shoulders thrown back and spine straight, Gene was a tall, slender, and severe attorney. He “wandered through the bldg. and classes,” Jones noted. “All students saw him; none recognized him.”

Despite this success, Jones would not be in London for much longer. His superiors believed his skills were also needed in the Pacific Theater. Before he departed in late October 1944, he began writing a 33-page manual titled “Personal Disguise” to be distributed to OSS bases. It covered everything he had taught to Gene and Bob and offered the same advice, in all caps, that an actor might hear on a Hollywood soundstage: “Disguise must be to a great extent an internal matter. The less there is of it on the outside the better.”

THE TRICKS AND TOOLS of a Hollywood makeup artist had served Jones well in London. The well-known brand names he relied on needed little adaptation for use in the agents’ European destinations. Max Factor No. 6 blue-gray eye shadow transformed alert eyes into tired ones on a backlot or in Vichy France. Arrid antiperspirant may have been more commonly found underneath arms in Los Angeles, but the same formula could be rubbed along the upper lip to keep a hair lace mustache in place in Slovakia. And Inecto Rapid hair dye was as convincing on the big screen as it was behind enemy lines—though only for assignments lasting fewer than two weeks, lest the spy’s roots begin to show.

The same was not true in China, Burma, India, and Singapore, where Jones was dispatched beginning in November 1944. There, the air was heavy and humid, mosquito repellent was essential, and the missions undertaken by the OSS’s Detachment 101 were those of a special-forces group, not of undercover agents. They ambushed Japanese troops, trained local militias, and rescued downed airmen. In Europe, Jones had been concerned with the close-up; spies had to withstand face-to-face scrutiny. In Asia, he was preoccupied with the long shot—the long shot of a Japanese sniper for whom a white American operative among brown-skinned local troops was an “automatic bull’s-eye.”

“It is absolutely essential to know the individual problems involved before it is possible to know the materials to use or how best to use them,” he argued forcefully in a memo to Lieutenant Kellogg. Each region presented its own challenges, and none of the methods that Jones had devised in London could be applied in Asia. “The wrong materials for a particular area are worse than nothing—They are dangerous as hell!”

The men of Detachment 101 needed something Jones did not have in his makeup kit. They needed “war paint.”

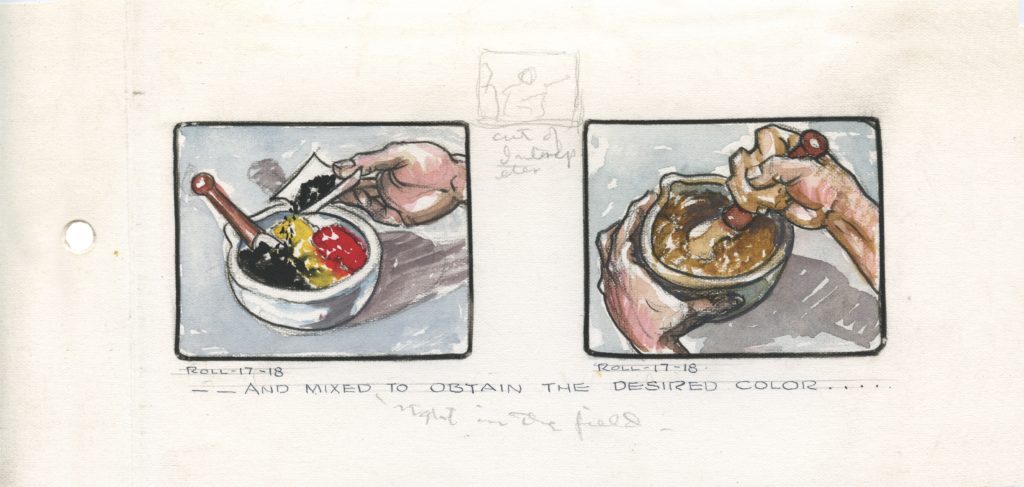

IN THE FOGGY ASSAM VALLEY of far eastern India, the resourceful Jones set about manufacturing a potent skin-coloring agent concocted from the same iron oxides that provided pigment for the eye shadows and lip rouges he was familiar with. It took much trial and error to find the combinations of red, yellow, and black oxides to mimic the complexions of the region’s different ethnic groups. “This is it,” Jones finally wrote in a February 6, 1945, memo smeared with a rusty red powder, which, when spread in varying amounts on exposed skin, could effectively disguise an outsider.

At first Jones made the war paint by hand, measuring the colors as carefully as he could in the field and grinding each batch for 15 minutes in a mortar. If he tapped and tamped the power, he could press 13.5 grams into a small, easy-to-hide vial, enough for 25 applications. Jones made 50 vials—about two days’ work—which were dropped for troops on and behind Japanese lines, and then made 100 more. When Colonel Ray Peers, commander of Detachment 101, requested another 3,000 vials, Jones enlisted the most prominent Hollywood cosmetics producer for help.

Max Factor & Company was synonymous with “makeup” in the motion picture industry. When the greasepaint sticks used in stage production proved inadequate for the early era of Hollywood, the company pioneered a creamy foundation that looked just right under studio lights. By the ’20s, the firm had a full line of film-friendly products and a reputation for beautifying the industry’s biggest stars, including Lana Turner and Rita Hayworth.

The cosmetics company supported the war effort publicly with Tru-Color lipstick—the brand on the lips of every pinup girl—and leg makeup, a liquid substitute for the nylon stockings rationed during the war. More quietly, Max Factor lent its research and development department to the U.S. government. Jones knew that the microgrinding machine used to produce fine powders for the firm’s cosmetics could make war paint. He rushed back to the States in the spring of 1945 to strike the deal and, with the company’s help, also developed a hair black that could withstand the sweat and rain of the jungle. The company hired extra help to fulfill the contract, and, by the end of the war, it produced at least 8,000 containers of skin and hair coloring to be carried by troops operating on the front lines in Asia.

Jones never received a credit for the most important makeovers he ever did, but some of his efforts were captured on film. In 1945, Jones himself produced an eight-minute movie for the Field Photographic Branch on the proper application of war paint. He carefully sketched out a storyboard and wrote and rewrote the script. The final scene, filmed on location in the Pacific Theater, introduces fellow OSS agent Bob Flaherty—“a man,” the narrator intones, “who knows this war.” The young guerrilla fighter looks like the type of leading man who would argue with Jones over the need for makeup, but Flaherty applies the war paint quickly and expertly.

“Do you like that stuff, Bob?” the narrator asks the agent.

“You’re goddamn right I do,” Bob mouths.

“Are you going to use it?”

“Hell, yes!” ✯

This article was published in the August 2020 issue of World War II.