In August 1966, with the Vietnam War raging, I enlisted in the U.S. Navy. I did not know where this would lead me, but it was a chance to explore my capabilities and an opportunity to learn a skill.

My first stop was boot camp at Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois. I remember using pieces of rope to hang out my laundry, standing inspection every morning, competing in group activities and learning to be an independent, responsible person. After boot camp concluded in late October, I became an “Airdale” (aka brownshoe), with my first set of orders sending me to the Naval Air Technical Training Center at Naval Air Station (NAS) Memphis, Tenn., for a 26-week electronics technician curriculum. Following completion of the course in June 1967, I took a couple weeks of leave and then departed on July 18 for three weeks of counterinsurgency training in Little Creek, Va.

As part of the Little Creek training, we endured a week surviving in the rugged outdoors during a very hot August. We ate whatever we could find (snapping turtle soup and smoked copperhead snake) while being hunted by an enemy (group of Marines) who eventually “captured” us (smoking the copperhead was a big mistake) and put our squad in a concentration camp for interrogation. At the end of concentration camp we were given some C-rations, which never tasted so good. After that I received my orders to report to Airborne Early Warning Squadron 1 (VW-1) in Agana, Guam. This is where my story really begins.

I departed Travis Air Force Base, northeast of San Francisco, in August 1967 on a chartered Boeing 707 jam-packed with military personnel for a 17-hour flight to Andersen AFB on Guam. It was like a can of sardines. Ventilation was not great and by the time I arrived at Andersen my legs felt like I was just learning to walk again. I was bused down to NAS Agana, where I checked in and was assigned to a barracks about a quarter-mile from the VW-1 hangar and airstrip.

When I arrived on Guam, I was an E-3 Airdale, therefore I started out as part of the flightline crew. We towed the Lockheed WC-121N Warning Stars that VW-1 flew and also directed the aircraft to a parking area upon their return from a mission. My first experience at nighttime was memorable. It was about 2 a.m. and the barracks duty officer woke me and told me to get to the hangar as quickly as possible. Two other Airdales and I met the “Super Connie” as it taxied off the landing strip toward the parking pad. My two buddies had the chocks for the wheels and I had the light wands to direct the pilot’s taxiing moves. Fortunately it was a clear night, so I could see reasonably well as I guided the aircraft to its designated spot between two other Super Connies, with room to spare on each side.

As a member of the flightline crew, I obtained all the necessary signoffs for the “practical factors” required before taking the E-4 Airdale exam. I was successful on my first E-4 exam, which put me on the waiting list to join an aircrew. A short time later, in December 1967, I was initially assigned to flight crew no. 7 as an aviation electronics technician (AT) petty officer 3rd class. Flight crew 7’s Warning Star had a roadrunner as its aircraft logo and our call sign was “Rainproof 7.”

As part of my training on the aircraft we flew many missions to track typhoons. As an AT, I supported, but was not limited to, avionics repairs. Since I was a junior aircrew member I also helped fuel the aircraft. We would remove the wing escape hatch and walk out approximately 15 feet or so from the tip tank, open up the fuel port, use a dipstick to measure the fuel level and then attach the fuel hose to the fuel port. Inside the aircraft, I maintained the radar consoles (four individual and one at the radar station) in the combat information center, my main responsibility. As CIC crew members, our responsibility was to monitor radar returns and identify any weather and aircraft that were in our vicinity, keeping our pilot aware of the details. This was back in the day when there were large cathode ray tube radar consoles and we used colored grease pencils to mark locations and objects on the CRT face. We also communicated with other aircraft and monitored their VHF radio transmissions, which came across as a high-pitched, echoing type of conversation. Pretty cool sounding.

Each VW-1 squadron aircraft had a primary search radar, the APS-20 (lower radome, range approximately 150-180 miles, depending on altitude); an electronic countermeasures station to monitor external radio frequency signals; and a height-finding APS-45 radar (upper radome). Every time the aircraft’s radial engines fired up, you would see a puff of bluish smoke and then they just purred like kittens. Seeing the smoke, smelling the fumes and hearing the engines roar just gave me goose bumps. It was exciting and got my adrenaline flowing!

More Connie tales

VW-1 had a total of 10 Warning Stars. About half were at Agana and the remainder were either on deployment or back on the mainland for periodic scheduled maintenance and refurbishment. The APS-20 was a real workhorse and rarely had maintenance issues. I do recall one time when we had to remove the maintenance cover over the magnetron for troubleshooting and a visual examination. The magnetron was a large glass vacuum tube and when that baby lit off it hummed and glowed the prettiest iridescent purple color you can imagine. On our airplane most of the electronic equipment backlighting was red and some light blue. (I have a Subaru Outback that has red backlighting for all the dash instrumentation and door controls. It is so reminiscent of the radar consoles that it brings back memories.)

Our squadron’s 10- to 18-hour typhoon reconnaissance missions encompassed the areas surrounding Guam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Okinawa and Japan. It was essentially a large triangular pattern, as the typhoons typically move westward over or around Guam and toward the Philippines, and then either straight into Vietnam or, later in the typhoon season, turn northward through Taiwan, Okinawa and Japan. Our deployment air bases were Naval Station Sangley Point in the Philippines (across the bay from Manila), Kadena AFB in Okinawa and NAS Atsugi in Japan.

Our crew typically consisted of six officers and 16 enlisted men, and in some cases there were individuals on board for various rating training. Once assigned to track a typhoon, we followed its westward course across the Pacific Ocean, gathering weather characteristics data using a dropsonde. The dropsonde was ejected from the aircraft’s weather station through a chute, then deployed a parachute to stabilize its descent and transmitted data to the aircraft weather station until it splashed down. The weather station was at the rear port side of the fuselage next to one of the “bubble” windows.

In the fall of 1968, I passed my E-5 exam, acquired my aircrew wings and became the CIC lead petty officer (LPO) for aircrew no. 4—a more pivotal role. Our typhoon reconnaissance missions in “Rainproof 4” became more frequent in the middle of the storm season. One mission, on October 3, involved a typhoon that originated about 1,000 miles east of Guam. As the typhoon headed toward Guam we were sent to evaluate its weather characteristics. It was just starting to grow in size and we did not know what was in store for us that day.

Our typhoon penetrations were typically “fasten your seat belt” bumpy rides that began with us flying just below the cloud cover to minimize turbulence. As we entered the typhoon’s weather bands, visibility started to degrade significantly, so pilot Lieutenant Melvin Thompson and copilot Lt. (j.g.) John Crossman resorted to flying via instrument flight rules (IFR), as the autopilot was no longer an option. Cockpit windshield wipers did their best to provide visibility, but the wind and rain overwhelmed them.

The key personnel during the typhoon penetration were the pilots, CIC officer and the CIC/LPO. With IFR instituted, the radar return was of extreme importance for determining the entry flight path. The CIC officer continuously communicated with the pilots via intercom during the penetration, with the CIC/LPO serving as his backup. The size of the typhoon determined the time needed to enter its eye, which was usually from 30 to 45 minutes. Once we entered the typhoon’s eye, there was always a sense of relief.

This particular mission started out as usual but went downhill from there. We were on station about 600 miles east-northeast of Guam, cruising at approximately 220 knots. When the typhoon was within range, we deployed a dropsonde to record its initial weather characteristics. It was standard procedure to deploy multiple dropsondes as we penetrated the typhoon. The CIC officer manned the main radar station while I backed him up on one of the CIC radar consoles. It was nearing dusk, which added some complexity to the mission as it was not the best time of day to penetrate a typhoon. Everyone was buckled in for what promised to be a very turbulent ride.

As we started our penetration, the typhoon’s outer bands were evaluated for the best flight path to minimize turbulence and risk to aircrew and aircraft. By viewing the radar image of the counterclockwise-moving outer bands, the CIC officer selected a path between two of the bands as our best route to enter the typhoon eye and gave the pilot a heading. We started our penetration nominally at 1,000 feet altitude, which kept us below the typhoon’s more deadly weather conditions. Unfortunately, the spiraling feeder bands became too tightly wound, creating an increasingly larger wall cloud for us to penetrate. The penetration path quickly became a high-risk situation.

When we were about a mile from the typhoon’s eye wall, we flew through a very turbulent cell cloud with a downdraft that almost pushed us into the ocean. The aircraft dropped several hundred feet in seconds before we stabilized, ending up approximately 300 feet above the water. As soon as we hit that cell cloud the pilots instinctively firewalled the throttles, which saved us. With the help of the 1st flight engineer, Chief Petty Officer Leroy White, they managed to stabilize our altitude so that we could enter the typhoon’s eye and circle up and out.

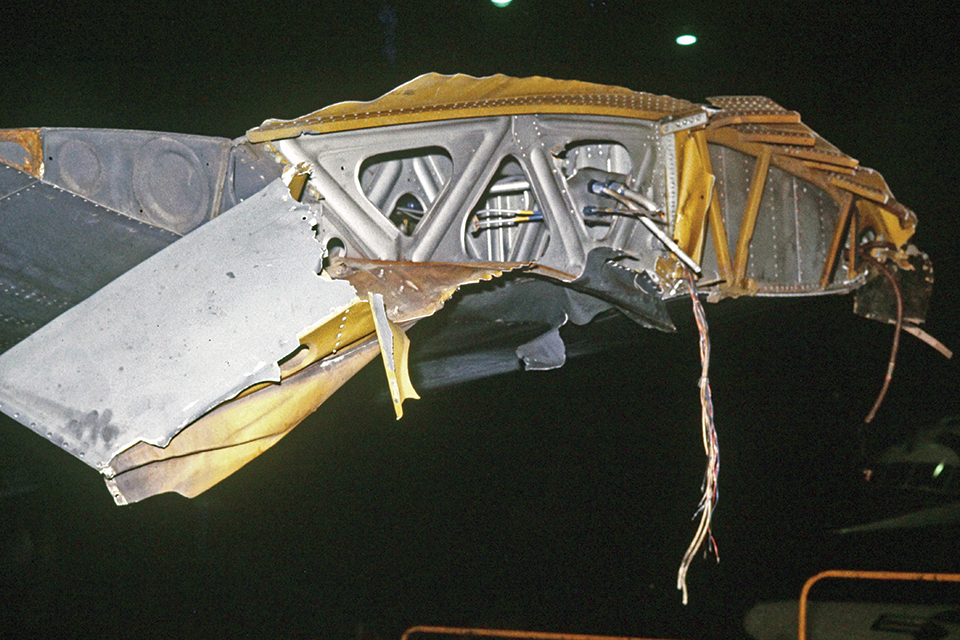

There was no visible damage within the aircraft, but White noted the instruments indicated the starboard fuel tip tank was empty. When the wing floodlights were turned on, he discovered the tip tank and approximately five feet of the starboard wing were gone! Lieutenant Thompson immediately declared a “mayday” and Andersen AFB sent out a Lockheed C-130 to escort us back to Guam. The physical damage to the airplane fortunately did not handicap our pilots’ ability to get us home safely.

As a result of the aircraft damage, a Captain’s Mast was held for this incident. As the CIC/LPO backing up the CIC officer, I testified during the Captain’s Mast and explained what I saw and my thoughts about the series of events. No one was punished as a result of the investigation, though I heard afterward that the CIC officer had a rough time of it.

In tracking a typhoon’s westward movement, we used various naval air stations and Air Force bases as our replenishment points. NAS Sangley Point was typically our first stop. Sangley’s runway was so short that upon landing the propellers had to be reversed at full throttle and brakes aggressively applied. A typhoon’s speed dictated when we had to leave so we could stay ahead of it.

Later in the season, typhoon paths curved northward rather than hitting the Philippines and then Vietnam. We would then use Okinawa’s Kadena AFB as our next deployment location. It was always quite a view because the B-52s were based there and once in a while we glimpsed an SR-71 Blackbird taking off. The Air Force had a weather command center at Kadena for tracking all the typhoons in the western Pacific.

On one of our missions in Rainproof 7, we flew directly to Kadena from Guam. I mentioned to our aircraft commander about having flown with my father when he piloted a Piper Cub back in the 1950s. After we had been airborne a couple hours, he called me up to the cockpit and asked if I wanted to sit in the copilot seat as we flew to Okinawa. I did not hesitate to say “yes.”

We chatted a bit and then he asked if I wanted to take the stick for a while. I was flabbergasted. He took the airplane out of autopilot and told me to grab the yoke. He coached me a bit and then I actually piloted (steered and maintained altitude) this beast for about 45 minutes. As soon as he let go of the yoke, the aircraft dropped a couple hundred feet until I pulled the yoke up to get it back at the correct altitude. Initially it took me several minutes to learn how to maintain altitude and trim. It was a great officer-to-enlisted-man gesture. After the copilot relieved me, I walked aft to the CIC area and everyone asked me if I was the one who gave them the roller coaster ride. That got a big chuckle.

Kadena AFB had many shops just outside the base that served military personnel. One of them made hang-up bags, so I bought one and had some of my squadron patches sewn on it. I added another patch that said “4th P,” which meant I was the crew’s “fourth pilot.” When the junior lieutenant who was our third pilot saw it and complained to our aircraft commander that I should not be allowed to have that patch, he just laughed it off. I guess the lieutenant felt slighted that an enlisted man was allowed to do that, but my 4th P patch stayed on my hang-up bag!

When the typhoons continued on a northward path (an infrequent occurrence), our next deployment location was NAS Atsugi. While visiting the base, some of us made a train trip into Tokyo, which was quite an experience since we did not know any Japanese. We just knew how many stops we had to make before getting off. In Tokyo I bought an Asahi Pentax 35mm camera that I used to shoot all my pictures.

It was not until years later that I learned Atsugi-based EC-121 Warning Stars routinely flew reconnaissance missions gathering electronics intelligence emanating from the North Korean peninsula. This had been going on for many years without incident. But in 1969 a MiG-21 intercepted a Warning Star over international waters and shot it down.

During my time with VW-1 I logged 1,451 total flight hours, of which 803 were combat flight hours over the Gulf of Tonkin. I was awarded three Air Medals. Every day was a new day and there was never a dull moment.

I had approximately 15 months remaining on my enlistment when I received orders to join a replacement air group, or RAG, at NAS Alameda in California. I was pleasantly surprised to get more shore duty with a training squadron, but then my orders were changed. The next set of orders told me to report to a Douglas A-4 attack squadron on USS Kitty Hawk. But that aircraft carrier was returning to the mainland after having just completed a deployment to the Gulf of Tonkin, so personnel said my orders were going to be changed a third time. Then I was sent to A-4 squadron VA-55 in Lemoore, Calif. The “Warhorses” were preparing for deployment to the Gulf of Tonkin.

Come to find out the commanding officer of NAS Agana had a policy that when you left VW-1 you would definitely have some sea duty. He was a firm believer that that was why you joined the Navy. I took some leave and in late April 1969 reported to NAS Lemoore.

As an aviation electronics technician (radar & radar navigation equipment) 2nd class, I familiarized myself with the A-4F aircraft electronics suite in preparation for deployment to Vietnam on the carrier Hancock. During our deployment I was responsible for the night shift electronics support of the VA-55 aircraft. I can say that there’s nothing better than nighttime launch and recovery operations aboard an aircraft carrier.

Upon being honorably discharged in June 1970, Mick Roy enrolled at Purdue University and earned his B.S. in electrical engineering technology in 1974. He worked for 40 years at Westinghouse (now part of Northrop Grumman) before retiring in 2014. Additional reading: College Eye: Lockheed EC-121 Warning Star and Related Technology in the Vietnam War, 1967-1972, by Sergio Santana; and Lockheed Constellation, by Curtis K. Stringfellow and Peter M. Bowers.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe!