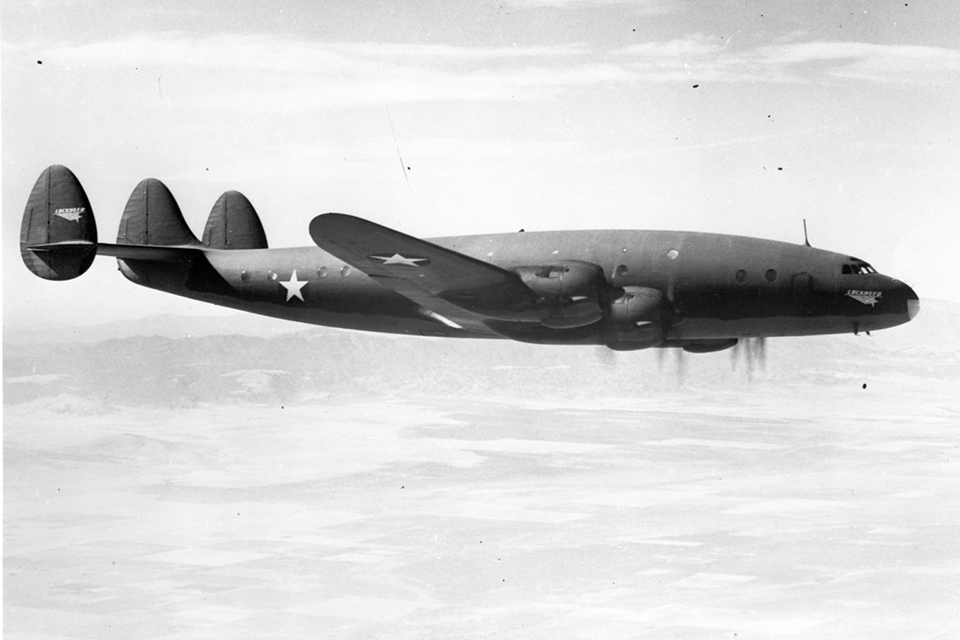

It was a source of some amusement (or terror, depending on one’s anxiety level) to Constellation passengers that the turbo compound engines spouted long tails of flame from their exhaust pipes

The Lockheed Constellation may be the object of more misinformation and fables than any other airliner ever made.

Howard Hughes designed it. (No. He designed Jane Russell’s cantilever bra, but he only specified the range and speed parameters he wanted for a new TWA transport.)

The Constellation’s fuselage is shaped like an airfoil to add lift. (No. It curves upward at the rear to raise the triple tail out of the prop wash and slightly downward at the front so the nosegear strut didn’t have to be impossibly long. Lockheed decided that the airplane’s admittedly large propellers needed even more ground clearance than did Douglas or Boeing on their competing transports, which resulted in the Connie’s long, spindly gear legs.)

It was known as “the world’s best trimotor” because it had so many engine failures that it often flew on three. (No. Boeing 377 Stratocruisers with R-4360 “corncob” engines had far more failures in airline service. There were a number of engine fires during the Constellation’s early development, but many airline pilots flew it for years without ever feathering an engine.)

The Constellation was the first pressurized airliner. (The Boeing 307 Stratoliner in fact was.)

The Constellation was the first tricycle-gear airliner. (The award goes to the Douglas DC-4.)

One Constellation passenger got glued to a toilet seat when cabin pressurization failed. (Actually, that one’s true. Stories of this happening on modern jets are urban legends, but Connies had far more primitive potties. When the valve that emptied the toilet into the unpressurized reservoir failed on one airline flight, the poor lady who happened to be in the blue room at the time became the cork that maintained cabin pressure. She was freed when the crew depressurized the airplane.)

Still, for an airplane that was produced in relatively small numbers by civil standards; that turned out to be a failure in its briefly spectacular ultimate version, the L-1649A Starliner; and that always played second fiddle to the more profitable, more economical and more easily manufactured competition from Douglas—the DC-4, -6 and -7—the Connie has lived in legend far beyond anything that its imaginative, graceful but complex design perhaps deserves. Stiff-necked Eddie Rickenbacker, the president of Eastern Air Lines, forbade his pilots to call the airplane “Connie,” convinced it sounded effeminate. Whether Captain Eddie’s prohibition had any effect on Eastern crews isn’t known, but the rest of the aviation world, which idolized the Connie, certainly ignored it.

When the Constellation was conceived, Lockheed was not a player in the air transport business. The company made some large single-engine “airliners” based on the Vega, as well as the Lockheed 10, 12 and 14 twins, all of which were blown away by the ubiquitous Douglas DC-3. Douglas, the industry leader, was already at work on its own four-engine, triple-tail design, the DC-4E. Boeing had a substantial background in large four-engine transports—the huge 314 Pan Am Clipper flying boats and the 307 Stratoliner under development—and even Martin and Sikorsky had more experience with big multimotors, with their own four-engine flying boats.

Lockheed was developing the P-38 Lightning and the Hudson patrol bomber, a military refinement of the Model 14, when company officials decided they needed to get in on the mini-boom in domestic airline travel that took place in the mid- to late 1930s. The obvious answer was a four-engine 14, and Lockheed called it the Model 44 Excalibur. No thanks, the airlines said—not big enough, not fast enough, not enough of a leap forward.

So in the summer of 1939, Lockheed began on its own to develop the Model 49 Excalibur A, soon to be designated the L-049 Constellation. It had the iconic fishy fuselage shape; a scaled-up P-38 wing; nacelles intended to hold four of the most awesome power plants of the time, Wright R-3350 supercharged twin-row radials; and an array of Fowler flaps borrowed directly from the Lockheed 14. The flaps were as precedential at the time as a 747’s array of fully extended tin laundry would be in the 1960s: 10 complex slotted sections on the wings plus a pair of center-section flaps under the fuselage.

An early Constellation proposal had the big radials cooled by reverse flow: cooling air went in via leading-edge wing scoops, blew through the engines from rear to front and exited between each engine’s prop spinner and the cowling ring. It looked cool, no pun, with bullet-shaped nacelle/spinner units that presaged the turboprop designs of the 1950s, but it turned out there was no significant cooling-drag reduction.

Another Lockheed brainstorm was a canard Constellation, a tail-first design. Not surprisingly, the airlines were entirely unreceptive to such a radical airframe.

But in any case, the L-049 was going nowhere. The winds of war were beginning to blow, and airline traffic was down. Douglas gave up on its DC-4E project—a complex and expensive-to-build prototype that had little to do with the actual DC-4/C-54 that would follow—and sold the plane to the Japanese. It would soon re-emerge briefly as the basis of the Nakajima G5N, Japan’s only long-range, four-engine bomber of World War II, an airplane that was built but never used.

It looked like the second iteration of Lockheed’s four-engine transport wouldn’t get off the drawing board either, but along came Howard Hughes with a secret order for 40 airliners, if Lockheed could meet his performance requirements. Hughes wanted to get a jump on his competition—mainly United and American—and not only demanded that the project remain quiet but stipulated that no other transcontinental airline be allowed to buy a Constellation for two years after Hughes’ TWA put them into service. American Airlines was so infuriated by being shut out that they vowed to never again buy a Lockheed airliner. Their pique lasted only until Lockheed’s next airliner, the turboprop Electra, was proposed in 1954. American ordered 40 the following year.

Much is made in some Constellation histories of Howard Hughes being a whack job, a crazy man, a weirdo. This is an exaggeration. The multimillionaire aviator’s true goofiness began with his addiction to painkillers as the result of the dreadful injuries he suffered while crash-landing the prototype Hughes XF-11 four-engine reconnaissance plane in July 1946. But he’d had his bell rung twice before in bad crashes during the late 1920s and mid-’30s, and they may well have done neurological damage that led to a case of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nobody knew what OCD was in those days, but if anything, it made Hughes a detail-oriented perfectionist.

In fact, Hughes was sharp enough to borrow the number-two prototype Constellation, a C-69 owned by the U.S. Army Air Forces. He quickly repainted it in TWA colors and used it to set a west-to-east transcontinental record in April 1944 from Burbank, Calif., to over Washington National in six hours and 58 minutes. His co-pilot was Jack Frye, TWA’s president, and Lockheed designer Kelly Johnson was along for the ride. (So was actress Ava Gardner, Howard’s girlfriend at the time.) Whether on this trip or another test flight, Johnson never developed any admiration for Hughes’ piloting skills. “He damned near killed us both,” Johnson once admitted.

On the return leg back to Burbank, Hughes stopped at Wright Field, outside Dayton, Ohio—today Wright-Patterson Air Force Base—and in a typically brilliant piece of PR picked up Orville Wright for Wright’s last-ever flight. Orville had been the pilot on the first true powered flight in history, and now he was given the right-seat chance to handle the controls of an airplane that, four decades later, represented some of the most advanced technology available to civil aviation—at this early point in the Connie’s life a 313-mph cruise, 2,850-mile range, 8,800 horsepower, hydraulically boosted controls and cabin pressurization. To put that into perspective, four decades ago the Boeing 707 had been in service for years, supersonic fighters were commonplace and the 747 had just made its first flight. Little is all that different today.

The Army Air Forces took over Constellation development and production in 1942, and that was, at least for awhile, the end of Howard Hughes’ grandiose plans and the unmasking of his “secret” airliner. The military needed big troop- and cargo-carrying transports, and the Constellation looked as if it would fill that bill.

The Connie’s temperamental Wright engines quickly killed the deal. Powerful but cranky and prone to pyrotechnics, the R-3350 so dismayed the Army Air Forces that it stopped C-69 production at just 13 (plus the prototype) and turned to the Douglas C-54 for its dependable airlift capability. The C-54 had Pratt & Whitney R-2000 engines of not much more than half the R-3350’s horsepower, but they ran forever and the C-54 was economical to build. The USAAF preferred that Lockheed concentrate on P-38s and Hudson patrol bomber derivatives anyway, and the R-3350 needed to be optimized for the upcoming B-29, forget about getting it to run in some damn airliner.

When the war ended, TWA quickly bought back from the government all the C-69s it could, and the Constellation finally went into airline service—though with Pan Am, in a flight from New York to Bermuda in February 1946. Three days later, TWA started Constellation service between New York and Paris, and a month later between New York and Los Angeles. In those days, Connies cost from $685,000 to $720,000, depending on equipment; in today’s dollars, that’s $7.6 million to $8 million—the price of a midsize bizjet. TWA and Pan Am, however, managed to buy four war surplus C-69s for $20,000 each and another two for $40,000 apiece.

Though the Boeing 307 was the first pressurized airliner, it was returned to service after the war with its pressurization system disabled, so for awhile only the Connie offered a high-altitude cabin. During its first two years of airline operation, however, two people were sucked out of Constellations in flight, thanks to the primitive pressurization system. One was a navigator lost when his astrodome popped off while he was taking a sextant shot; the other was an Air France passenger sitting next to a cabin window that failed. Amazingly, brave passengers continued to board Connies.

In 1946 a Pan Am Connie en route from New York to London had an engine fire soon enough after takeoff that the airplane was able to return and belly-land on a 4,500-foot grass strip in Willimantic, Conn. There were no injuries to the crew or passengers, which included Laurence Olivier, his then-wife Vivian Leigh and other members of the Old Vic repertory company. The fire had burned through the engine mounts by the time the airplane was back over land, and the big radial and its prop dropped off entirely and fell onto a farm field. Fortunately for all on board, Lockheed, obviously aware of the flammability of the Wright engines, had designed the Constellation’s nacelles and stainless steel firewalls to encapsulate even a raging fire for 30 minutes.

When the airplane was repaired, it took off from the grass strip lightened as much as possible and with minimal fuel. Still on three engines, it was airborne in 2,000 feet. Back at Pan Am’s LaGuardia maintenance hangar, the remains of the number-three nacelle were removed, the hole in the wing was faired over and the Connie flew back to California for major work. Until the advent of the Boeing 727, it remained the world’s fastest trimotor.

By 1948, it looked like the Connie was done. Airline economics were lousy, and Lockheed didn’t have enough Constellation orders to keep the line open. Game over? Not quite.

Out of nowhere came an order from the U.S. military for C-121 multiuse transports and from the Navy for PO-1 long-range patrol planes (“Po-Boys” they were quickly dubbed). Lockheed had been saved by the bell. It had already developed the Model 649 and 749, with higher-horsepower engines, far more comfortable cabins with rubber isolation mounts between double skins for noise suppression and a number of other improvements. These were really the first true Constellation airliners, the L-049 having been essentially a military transport converted to civil use. The government order allowed the 649s and 749s to stay in production, and 131 were built for airline use. One went to Howard Hughes (he would eventually also have for his personal use two Hughes Tool Co. L-1049Gs and a TWA L-1649A Starliner), and 12 went to the military.

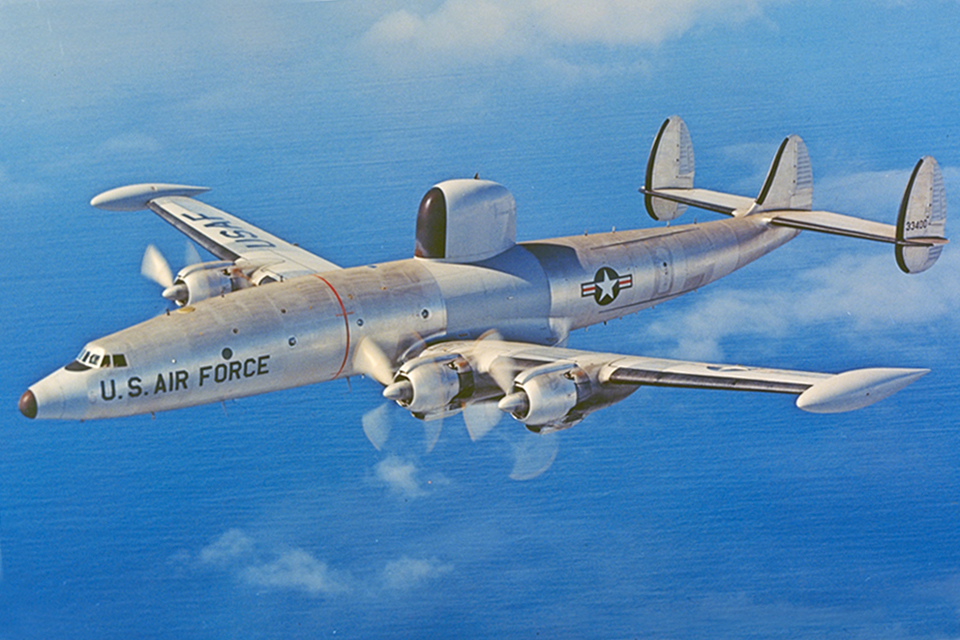

The Constellation was arguably more successful as a military airplane than it ever was as an airliner. The USAAF, USAF and Navy bought and used nearly 40 percent of all the Constellations ever manufactured, and Connies were the direct predecessors of today’s AWACS jets and pioneered just about every form of airborne electronic reconnaissance. The alphabet nearly ran out of letters to designate C-121 variants—RC, EC, NC, VC and YC, from A models right through to Js, Ks and the Navy “Willy Victors,” WV-2s. Constellations carried the first of the enormous rotating radomes—rotodomes—that preceded the flying saucers atop 707-derived Boeing E-3s that today routinely prowl Middle Eastern skies. Their early analog electronics could consume enough electricity to power an entire town of 20,000 people. Constellations remained in service with the U.S. Navy until June 1982 (six years after the Concorde went into supersonic airline service), and were operated by India’s navy until 1984.

The Navy was responsible for the complex but enormously powerful Wright R-3350 Turbo Compound engine, which led to successful development of the originally underpowered L-1049 stretched Super Constellation. The engines were initially intended for the Lockheed P2V-4 Neptune, a late version of the Navy’s primary long-range patrol bomber. They are sometimes referred to as being “turbocharged,” but in fact the power plant’s exhaust-driven turbines had nothing to do with pressurizing induction air. Each engine had three power-recovery turbines that fed power back into the engine through long lateral shafts geared directly (via a fluid coupling) to the crankshaft. The torque of the engine’s PRTs added 150 hp, uprating it to 3,400 hp. Other than modified engines in Reno racers, the only more powerful production piston radial was the far larger, 28-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-4360, at 3,500 hp.

It was a source of some amusement (or terror, depending on one’s anxiety level) to L-1049H and later L-1649 passengers that because of the exhaust constriction, turbo compound engines spouted long tails of flame from their exhaust pipes, particularly at night. Indeed, Lockheed would fit stainless steel leading edges to the wings adjacent to the nacelles to prevent damage from the big blowtorches.

The ultimate Constellation is popularly considered to be the Model 1649A, though the Starliner (which is what Lockheed named it) was in fact a new design, with an entirely different, far longer wing than the true Constellation/Super Constellation line had. Oddly, the new straight-taper, high-aspect-ratio wing had not a modern laminar-flow airfoil but a thin NACA airfoil like the one on Boeing’s B-17s and 314 Clipper flying boats. The Starliner (TWA called theirs Jetstreams, perhaps to suggest it had something in common with the already-proliferating Boeing 707) was the largest American piston airliner ever produced and the fastest by far at long-range cruise power settings, but it was a failure. Just 44 were manufactured, including Lockheed’s own prototype. It was the company’s only unprofitable series in the Constellation/C-121/Starliner evolution.

By 1961, even the newest Constellations were beginning to move to second-tier airlines and then to the likes of Royal Air Burundi, Slick Airways, Flying Tiger, Pakistan International and Britair East Africa. Because many Connies were low-time airframes when they were retired by the big airlines in favor of 707s and DC-8s, they were particularly desirable to a variety of users. Many Constellations became freighters, crop sprayers, travel club ships, charter birds, firebombers and smugglers. One was even specially equipped to airdrop bundles of marijuana and was openly tested in Arizona with hay bales, after being given a dispensation by the FAA for “agricultural flights.” The Rolling Stones used an ex-Eastern 749 for part of their famous 1972 U.S. tour, emblazoned with big tongue-and-lips Stones logos.

The final circle of aviation hell achieved by a surprising number of Constellations was conversion into restaurants, cocktail lounges, discos and nightclubs, perhaps the best known of which, an ex-KLM bird, ended up in New Orleans as the Crash Landing Bar.

What would Orville Wright have thought of that?

For further reading, frequent contributor Stephan Wilkinson recommends: Lockheed Constellation, by Curtis K. Stringfellow and Peter M. Bowers; and Lockheed Constellation: From Excalibur to Starliner, by Dominique Breffort.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2009 issue of Aviation History. Click here to subscribe today!