When naval construction battalions weren’t building bases, they were fighting the enemy.

On the morning of July 1, 1967, Chief Petty Officer Joseph Herrara of Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 11 was driving a truck near Da Nang Air Base when a lone Viet Cong soldier fired a poisonous dart that shattered a window and caused a deep gash in the chief’s arm. Realizing he was under attack, Herrara switched off the engine and got out. As he ran toward the back of the truck, a bullet struck his belt loop. He drew his pistol and made his way to a ditch across the road. He spotted the Viet Cong and fired four rounds before chasing him. The Viet Cong threw a grenade, and Herrara hit the ground, waiting for an explosion that didn’t come. He slowly rose and inspected the grenade; its safety pin was still partially in place. The Navy construction man had survived the sudden attack.

Two years earlier, on June 10, 1965, steelworker Petty Officer 2nd Class William C. Hoover from the same battalion was less fortunate. When Viet Cong attacked the U.S. Army Special Forces camp at Dong Xoai, about 55 miles northeast of Saigon, Hoover was wounded in the initial mortar shelling but continued firing and was killed later in the battle. Posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” device for valor, Hoover was the first person from the Navy’s construction battalions—abbreviated CBs and called “Seabees”—killed in the Vietnam War.

Trained for combat as well as construction, Seabees frequently found themselves in the thick of the fighting and just as often distinguished themselves with their heroism. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., includes 85 Seabees among its list of war dead—a tribute to their motto, “We build, we fight,” which is symbolized in their logo of a bee holding a wrench, hammer and machine gun.

I served in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969 as a swift boat maintenance and repair electrician aboard the landing craft repair ship USS Krishna. We were anchored near An Thoi, a fishing village on the southern tip of Phu Quoc Island in the Gulf of Thailand. When the site became the home of the first swift boat division in Vietnam in December 1965, the Seabees were short on virtually everything needed to build the base, so the Krishna served as their supply depot. That all changed after Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze visited in 1966. After living in a tent for a few days and taking part in some swift boat patrols, Nitze made sure the Navy delivered the materials needed to make life at least a little more bearable. In short order, the Seabees, with a hand from the Krishna and swift boat crews, had the buildings up and occupied, including Quonset huts, the military’s old standby in prefabricated metal structures used for officers housing, storage and recreation.

The Seabees at An Thoi were continuing a tradition that began in the summer of 1940 when the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks began to build Naval Air Station Quonset Point, near Davisville, Rhode Island. The new huts were designed in two primary sizes—20 feet by 48 feet and 40 feet by 100 feet—and could be connected side-by-side and end-to-end, offering numerous configurations.

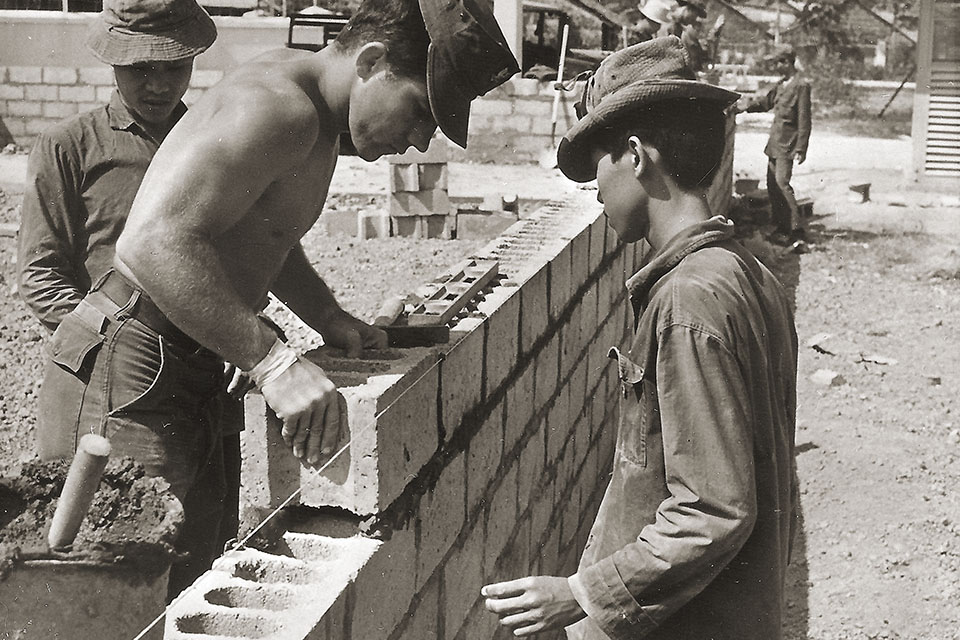

was a priority for Seabees, who trained Vietnamese in construction techniques. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

In the 1930s, as Japan’s expansion in the Pacific increased the prospects for war, the Navy had begun building bases on islands in the region. The work was initially done by civilian construction contractors, but after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor pushed the United States’ into war, the Navy needed to replace the civilian workers with military construction personnel who could engage in combat if necessary.

On Jan. 5, 1942, Navy officials authorized the Bureau of Yards and Docks to organize battalions of armed military construction workers. Within days, men just out of basic training gathered at Quonset Point to learn how to use construction equipment and build the huts before shipping off to Charleston, South Carolina, where they established the Navy’s first construction unit on Jan. 21. Although called a construction battalion, the unit comprised only 250-300 men—not much bigger than a company. One week later they shipped out to build a fueling station on Bora Bora. The men, initially dubbed “Bobcats,” after the operation’s code name, reached Bora Bora on Feb. 17.

The Navy officially named its construction battalions “Seabees,” on March 5, 1942. Ten days later in Norfolk, Virginia, the Seabees formed their first true battalion-sized unit with a headquarters organization and four companies, totaling about 1,000 men. In April the battalion split into two detachments, and each sailed to different islands in the Pacific. Although the first Seabees went to the war zone with little more than basic training, by the end of June 1942, the Navy had established “advance base depots” for advanced military and construction training in Davisville; Port Hueneme, north of Los Angeles; and Gulfport, Mississippi.

During World War II, about 325,000 Seabees served on six continents and 300 islands. Their gallantry caught the attention of Republic Pictures Corp., which released The Fighting Seabees, starring John Wayne, in January 1944.

Rapid postwar demobilization left the Seabee force with just 2,800 men at the onset of the Korean War on June 25, 1950. The Navy quickly put about 10,000 members of the Naval Reserve Seabee program on active duty, and Seabees were among Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s troops who landed at Inchon on Sept. 15, 1950, and forced a North Korean retreat. An armistice that stopped the fighting and set up a demilitarized zone was signed on July 27, 1953.

Three years later, in the summer of 1956, a team of Seabees arrived in the Republic of Vietnam, created just two years earlier when the country was split into a communist North and noncommunist South after French colonial rule ended. The Seabees’ initial task was to survey approximately 1,800 miles of current and proposed roads across South Vietnam. They worked seven days a week for two months in challenging terrain and then left Vietnam after completing their assignment. Years later, those surveys would be crucial in the construction of roads essential for U.S. military operations in the country.

In 1963, Seabee teams were once again in South Vietnam, constructing U.S. Army Special Forces camps being established to help counter the political influence and armed threats of the Viet Cong in rural areas. The Seabees also assisted civilian communities with projects that included construction of hospitals and storage facilities and digging wells for drinking water.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, passed by Congress in August 1964, gave President Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to send combat troops to Vietnam. On March 8, 1965, the Marines were the first ashore, landing at Da Nang in the northern part of South Vietnam. On May 7, Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 10 was the first Seabee battalion in Vietnam after the introduction of combat forces, arriving to build an airfield for the Marines at Chu Lai.

Dozens of other Seabee units soon followed, including more than 20 mobile construction battalions, the 3rd Naval Construction Brigade, the 30th Naval Construction Regiment, the 32nd Naval Construction Regiment, construction battalion maintenance units 301 and 302, and amphibious construction battalions 1 and 2. Seabees served in 22 provinces from the Mekong Delta, up through the Central Highlands, to the border with North Vietnam at the Demilitarized Zone. They not only performed their assigned construction tasks for the military, but also helped teach the Vietnamese construction techniques.

Early on, the Seabees discovered that there would be many times when they had to put down their hammers and pick up their weapons. Among the most prominent gunfights in Seabee lore is the June 1965 Dong Xoai battle in which Hoover was killed. The American camp at Dong Xoai was defended by 11 Special Forces soldiers and nine members of Seabees Team 1104 from Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 11. Seven of the Seabees were wounded, and killed along with Hoover was Petty Officer 3rd Class Marvin Shields, a construction mechanic. Shields posthumously received the Medal of Honor for carrying a wounded man to safety and destroying a Viet Cong machine gun emplacement before dying. He was the only Seabee awarded the nation’s highest honor and the first Navy man to receive it in Vietnam.

In October 1965, the Viet Cong attacked the Marble Mountain airfield, just south of Da Nang, inflicting severe damage on U.S. aircraft and a base hospital being constructed by Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 9. Eight Seabee-built Quonset huts used for X-rays, labs and surgical wards were destroyed. Two Seabees were killed and more than 90 wounded. After the attack it was—as always—“all hands on deck” to rebuild the hospital and living quarters. The Seabees accomplished that task in just three months.

FedEx Corp. CEO Frederick W. Smith, who served two tours in Vietnam as a Marine officer, worked with Seabees during the war. “I first saw the Navy Seabees’ abilities at Marble Mountain, where I was stationed in Vietnam on my second tour,” Smith recalled in 2016. “The Seabees built this airfield, bulldozing sand dunes and laying steel runways to accommodate heavy traffic. They also built a 660-tent camp and a huge mess hall, working alongside Marines under tough conditions, including enemy fire.”

By the final months of 1965 the Seabees had established large bases in Da Nang, Chu Lai and Phu Bai in South Vietnam’s northern provinces. The bases provided combat forces the support required to increase their attacks and were instrumental in defeating Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army offensives around the Demilitarized Zone and Laotian border.

As U.S. forces in South Vietnam gradually increased, so did the need for Seabees to build facilities for those troops. In mid-1965 there were 9,400 Seabees in Vietnam, and that number increased to 14,000 over the next 12 months. By 1967 there were 20,000, and over the following two years the number peaked at more than 26,000. Typically, deployed Seabees spent eight months in Vietnam, returned stateside for six months in Davisville and then went back to Vietnam for a second eight-month tour.

To support the demand for Seabees, the Navy made a concerted effort to recruit skilled construction trade workers. Using advanced pay grades as an incentive, a program for “direct procurement” of petty officers was very effective: More than 13,000 signed up.

In 1966 the Seabees were expanding the initial bases and building permanent facilities for men and equipment. They went into Quang Tri, the province closest to North Vietnam, to construct concrete bunkers overlooking the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and they built structures for the Marine base in Dong Ha, about 12 miles south of the DMZ.

The next year brought still more construction projects. An airfield in Dong Ha and Liberty Bridge south of Da Nang were on the Seabees’ endless “to do” list. Despite the challenges of working during the monsoon season, they finished the airstrip in 38 days. The bridge, more than 2,000 feet long, was completed in five months. Among the other projects in 1967 was the construction of officers housing for swift boat skippers in Chu Lai.

The ever-resourceful Seabees also created barbecue grills from modified 55-gallon drums that had drilled-out sections of deck plate installed on them for cooking hot dogs, hamburgers and even chicken. We had one at An Thoi and used it when we visited a nearby island beach.

tasks that included constructing huts for the Marines, laying pipes, working on power distribution systems and surveying more than 1,000 miles for roads across Vietnam, a crucial job done in challenging and dangerous conditions—sometimes in enemy-held territory. (U.S. Navy Seabee Museum)

When the communists’ Tet Offensive began on Jan. 31, 1968, the Seabees were on the battlefield alongside the Marines and Army. Much of South Vietnam’s third-largest city, Hue, in the northern part of the country, crumbled during the struggle, and Seabees stationed about 8 miles to the south at Phu Bai were called to rebuild a critically needed concrete bridge. After enemy snipers began to fire on the construction team, it immediately formed a combat force, eliminated the sniper fire and finished the bridge. In spring 1968, the Seabees rebuilt the railroad from Da Nang to Hue, completing a project that had been halted for three years due to relentless enemy fire.

American military operations were significantly reduced after June 1969, when President Richard Nixon announced his Vietnamization policy of gradually withdrawing U.S. troops and transferring combat responsibility to the South Vietnamese. But the Seabees continued to be busy. For instance, they built coastal bases and radar operation centers in the Mekong Delta that enabled the South Vietnamese to assume coastal surveillance operations previously conducted by American swift boats.

On June 23, 1970, the last units of Seabees left Vietnam from Chu Lai’s Camp Shields, a site that had been renamed in September 1965 to honor the Medal of Honor recipient. Their work had not only assisted the military but also improved the lives of South Vietnamese civilians. They had built bridges, docks, schools and hospitals. They had dug wells and paved roads to provide access to farms and bring medical treatments to villagers. Such efforts proved the Seabees were not just fighters, but also “builders of peace.”

After his discharge from the Navy, Tom Edwards earned an engineering degree and spent most of his career as senior facilities engineer with General Dynamics-Space Systems Division in San Diego. He thanks Jack Springle of the Seabee Museum and Memorial Park and Bob Bolger and Bob Brown of the Swift Boat Sailors Association for their help with this article.