In 1964, the Republic of Korea (ROK) dispatched soldiers to assist the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) in its fight against communism. Recovering from its own terrifying and bloody brush with communist aggression just a decade prior, ROK President Park Chung-Hee offered to help his ally, the United States, prevent another Asian country from turning “Red.” That first brigade of engineers, doctors, and military police grew to two Army infantry divisions and a Marine brigade within two years, fighting in some of the nastiest campaigns of the war.

By the time ROK forces withdrew from Vietnam in 1973, over 320,000 Korean troops had rotated through the war zone—the second largest foreign contingent in the war after the U.S. Korean troops in Vietnam left behind over 5,000 dead, 11,000 wounded, and a hard-earned reputation as ferocious and stubborn fighters that continues to characterize the ROK armed forces today. Although born in the crucible of the Korean War, the ROK Army and Marine Corps were forged by their experiences in Vietnam into a modern and effective fighting force.

South Korean Support For America

It is always the case that a long trail of logistics and support personnel makes it possible for brave men at the front to do brave things. This was no less true in Vietnam and proved just as necessary for the ROK during its first-ever combat deployment overseas. Without a global base structure of its own, the ROK relied on allies and partners to assist with the logistical support necessary to keep two infantry divisions and a Marine brigade in the fight. Clark Field in the Philippines and Ching Chuan Kang Air Base in Taiwan provided such assistance to South Korea and were integral to the 1972-73 Vietnam experiences of now retired ROK Air Force Col. Han Jin-Hwan.

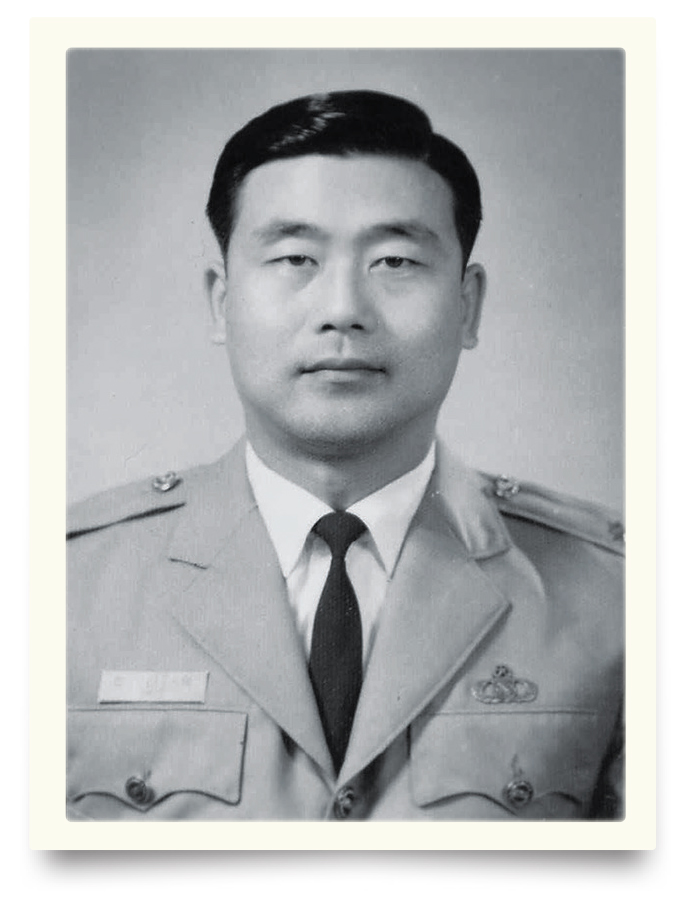

Col. Han joined the ROK Air Force in 1959 after graduating from Chung-ang University in Seoul. Trained as a weapons controller, his stellar service record and exceptional proficiency with the English language led to his selection to attend the Defense Language Institute at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas from 1964-65. Then he went to Weapons Controller School at Tyndall Air Force Base and the Air-Ground Operations School at Hurlburt Field—both in Florida—through 1966. Col. Han retired from the military in 1983 after a distinguished career and remains a civic leader in his community today.

In autumn 2023, he agreed to sit down for an interview with Vietnam magazine—the first interview of its kind this magazine has featured—to share his experiences with readers in the United States.

Col. Han, where are you from in Korea?

I was born and raised in Seoul, the capital of the Republic of Korea.

What did your parents do and what was it like growing up?

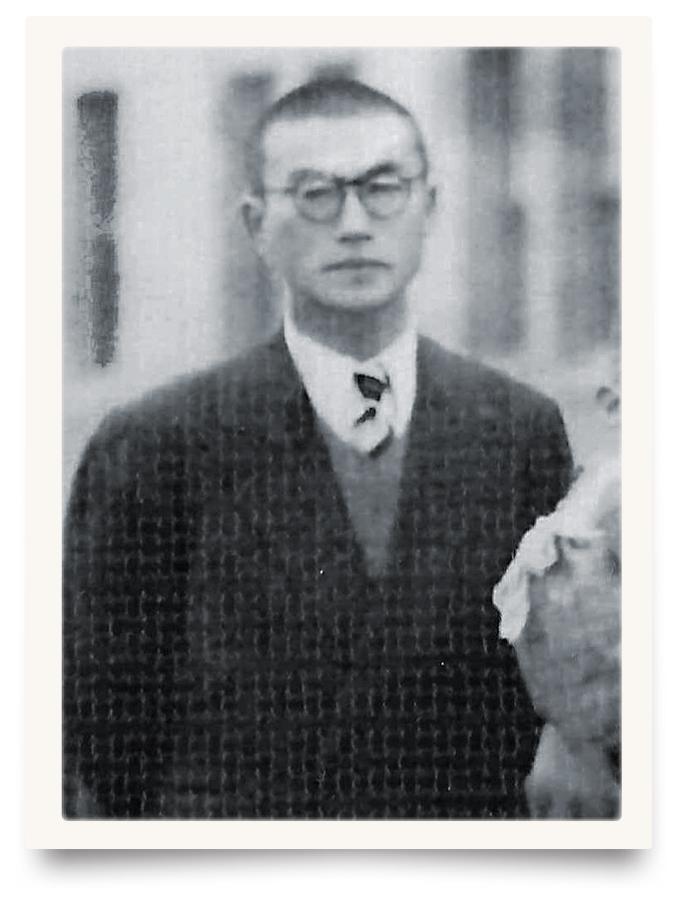

My father [Han Sang-Jik] was a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Public Affairs. In 1950, when North Korea invaded, we couldn’t evacuate to the south and so were forced into hiding. A friend of my father’s talked him into coming out into the open where he was then captured by the North Koreans. That “friend” turned out to be a communist sympathizer.

My father was taken North with many other public officials and we never saw him again. I was 12 years old at the time.

I always remembered three things my father taught me: “If you start something, never give up until the very end,” “Always be diligent,” and, “Always be a good person.”

Were you drafted or did you volunteer to go to Vietnam?

I volunteered, though not in the way you Americans did. I’d joined the ROK Air Force in 1959, and so in 1972 I was a major working directly for the Chief of Staff of the ROK Air Force. He asked me at the time where I wanted to serve next and I told him Vietnam.

It was hard for Air Force officers to go there at the time as there were few of our personnel in Vietnam, so competition for the few slots was high. Since I asked the Chief of Staff directly, he agreed and made the arrangements.

What inspired you to volunteer?

I felt strongly ever since 1950, when the United States came to our aid and helped our country beat back the communist North, that Korea owed a debt to the U.S. We were poor then with few modern weapons and little ammunition.

A lot of equipment was shared with us and many U.S. soldiers died on our behalf. President Park decided the ROK would dispatch troops to Vietnam and I wanted to do my part to help repay that national debt.

Did you receive any special training before deploying to Vietnam?

Due to the nature of my mission the only training I received took place at the Ministry of National Defense in Seoul.

What unit did you serve in?

I served in the Air Force Support Group, with its headquarters located at Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon. As it turned out, I only stayed there for three months before being dispatched to Clark Field in the Philippines as ROK Liaison Officer.

When did you first arrive in country and what was it like?

Late May 1972, on a ROKAF C-54.Saigon wasn’t exactly the frontier. We stayed at a small hotel. The soldiers and airmen stationed at Tan Son Nhut didn’t really feel the war like the men did out in the jungle. Our infantry were at the front and fighting, but would come back to Saigon for rest and recovery. My wartime duty station was a recovery site for others!

What was your mission there?

I handled all coordination for ROK personnel—military and civilian—moving between Korea and Vietnam. I managed a small village full of trailers for our people to overnight in when necessary. My NCO and I also provided escort duty to the medevac flights taking our wounded and dead from Vietnam back to Korea.

These missions were all-day flights for us, on ROKAF C-54 and C-9 aircraft specially adapted to transport litter and ambulatory patients. The medevac flights routed from Vietnam to Taiwan and then on to Daegu, Gimpo, or Gwangju Air Bases in Korea.

During the layover in Taiwan I arranged for meals—regular or soft food—and handled all financial transactions required as well as making whatever arrangements were necessary with the nursing staff. After landing in Korea and unloading both our wounded and deceased members, we had four hours before the return flight to Clark. Those missions took all day starting with a 3 a.m. briefing at Clark and not returning till late at night.

My duties required me to have dealings with the U.S. military hospital at Clark. That facility was very large and a lot of wounded and deceased U.S. soldiers came through there. I remember seeing so many coffins.

Did anything surprise you about Vietnam?

You couldn’t tell friend from foe. You couldn’t look at someone and see whether or not they were communists. Because of this, the Support Group commander, Lt. Gen. Lee, instituted a curfew and so we weren’t allowed into the city at night.

Did you interact with local Vietnamese and, if so, what did you think about them?

We used to visit “Chollum” [sic] market. At the time I bought a set of 10 ceramic plates decorated in a French style for my wife. I still have three or four. People in the market smiled at us and treated us nicely but we always wondered if they weren’t really communist at heart. That said, unit regulations prevented us from any significant interaction with the locals.

How hard was it to do your mission, and how long did it last?

At times it was very difficult—especially the medevac flights—but I felt then that it was a job worth doing and I was honored to do it. I was very patriotic at that age and since I couldn’t go to the forward areas and fight, I really wanted to help those who’d been wounded doing so. There was a lot of job satisfaction for me there. Still, it was very hard for me to see our soldiers that way.

It was a one-year tour for me, 1972 to 1973. Three months at Tan Son Nhut and then nine more at Clark.

Do you recall any particularly memorable experiences while performing that mission?

So many. Some of our wounded had been blinded or lost limbs. It was pitiful to see them so badly injured. They were all so young, so full of life, but dedicated to the mission there and ready to sacrifice. I felt…it was just very pitiful to see them that way.

Did you work with American troops in Vietnam? If so, what was your experience with them?

I didn’t really work with Americans in Vietnam, but of course I worked with so many stationed at Clark Field. I thought they were generally very good soldiers and very patriotic.

How many trips did you make to Vietnam?

The medevac flights took place roughly once every three weeks or so. My NCO and I took turns escorting the medevac flights and so I made three or four trips back into Vietnam. He was a medical Technical Sergeant.

Besides soldiers, what kind of people passed through Clark from Korea?

Lots of entertainers, assemblymen, even Miss Korea, but not many so late in the war.

Was your family concerned for your welfare?

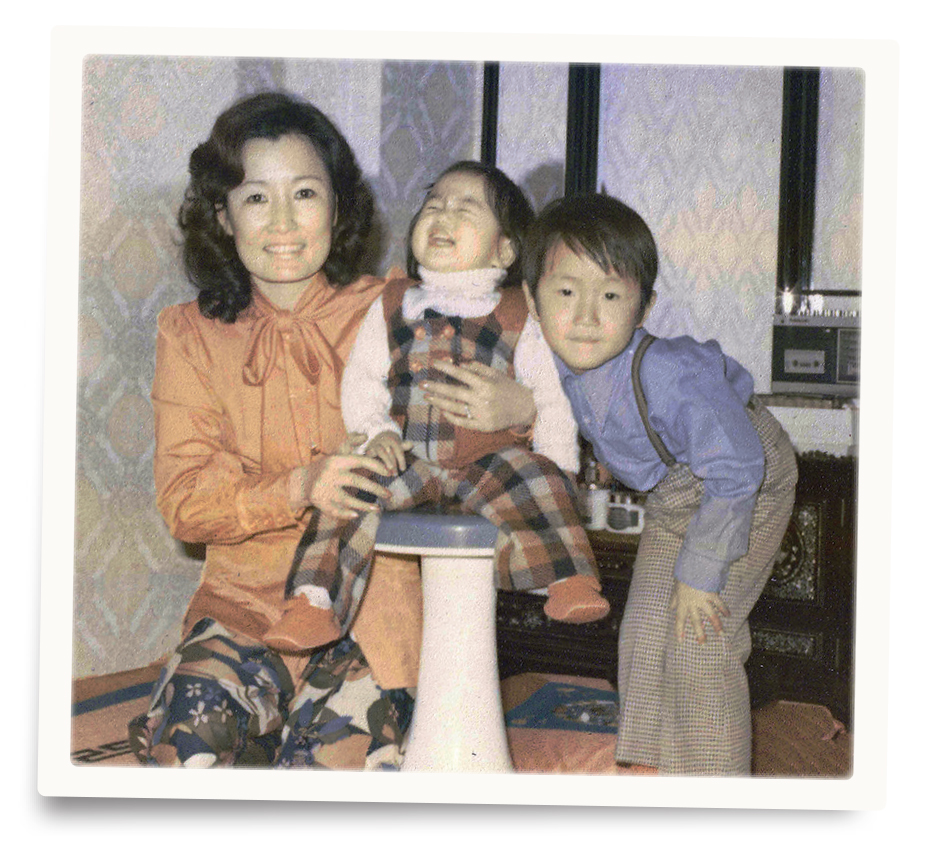

They were concerned, but I received combat pay while deployed to Vietnam and so that was good news. It was a lot of money for us back then and my wife saved up the excess pay to buy an apartment in Seoul. I remember my daughter was born halfway through my tour of duty, in 1973. Because I had access to the U.S. Air Force Base Exchange on Clark, I bought a bunch of baby clothes and sent them home to my wife. These things helped them and took their minds off the fact that I might be in a dangerous situation.

How did you feel when the U.S. withdrew from Vietnam?

It all kind of felt like a waste of time, and I hated the thought that the communists had won after all. It made me think that no matter how much help might be given, we could never change peoples’ ideology. It was the same with North Korea. The experience left me, if anything, even more anti-

communist, more dedicated to protecting our freedoms than before.

When you returned to Korea from your deployment, did you face any negativity because of your experience in Vietnam?

No, none at all. The government thanked us for our service in Vietnam and gifted us our first color television and a new refrigerator. You laugh, but there weren’t many color TVs in Korea in 1973, so we felt special. The military handed us coupons upon our return and we just went into a store and walked away with the new appliances. Our going to the war really wasn’t a political or social issue back then, though you must remember we had a military government at the time so protests were difficult.

Still, our participation in the Vietnam War didn’t become an issue at all until later, when left-leaning politicians used it for political gain. At the time, we were welcomed back home and those who returned with me just felt lucky to be alive.

Have you been back to Vietnam since the war ended?

No…and don’t really have any desire to do so. That was a long time ago.

Is there anything you would like to say to Vietnam veterans in the U.S. reading this story?

The U.S. veterans of that war were heroes for standing up to the spread of communism overseas. I think it was a very difficult experience for them and I appreciate it so much.

What would you like young people to know about the Vietnam War?

War is a very cruel and difficult thing. My generation knew war and poverty, precisely because of communist aggression from North Korea and later North Vietnam. Our young must be thankful to their elders for all our sacrifices, but they know nothing of war or difficulty. They can’t understand enduring poverty, death, and destruction because of the communists up north. It’s all ancient history to them—almost like a fairy tale. This is why they lean toward leftist ideas. They just don’t understand what happened the last time those ideas marched south.

Is there anything you would like to add?

It seems rich countries always feel the need to help poorer countries.

And yet the ROK was quite a poor country when it decided to help South Vietnam.

Yes, and in a strange way, it ended up being our nation’s pathway to material success and the prosperity you see in Korea today. Our sacrifice served our nation well.

This interview appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of Vietnam magazine.