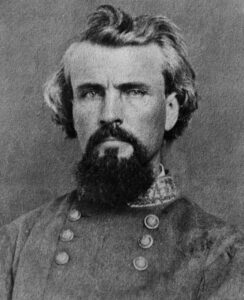

Facts, information and articles about Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate General during the Civil War

Nathan Bedford Forrest Facts

Born

July 13, 1821, Chapel Hill, Tennessee

Died

October 29, 1877, Memphis, Tennessee

Highest Rank Achieved

Lieutenant General

Battles Engaged

Fort Donelson

Battle Of Shiloh

Civil War Battles Battle Of Nashville

Battle Of Fort Pillow

Battle Of Chickamauga

Notable Facts

Innovative Cavalry Leader

First Grand Wizard Of Ku Klux Klan

Nathan Bedford Forrest Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Nathan Bedford Forrest

» See all Nathan Bedford Forrest Articles

Nathan Bedford Forrest summary: Nathan Bedford Forrest was born in Bedford County, Tennessee, the eldest of twelve children. Forrest became a millionaire as a businessman, who owned several cotton plantations. He was also a slave owner and trader.

Nathan Bedford Forrest In The Civil War

Forrest volunteered as a private in the Confederate Army on June 14, 1861, but at the request of Tennessee’s governor, Isham G. Harris, he raised and equipped an entire cavalry battalion at his own expense; the former private was made a lieutenant colonel. He would rise to command the cavalry corps in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana and would end the war as a lieutenant general. Though he had no formal military training—indeed, he had only six months of formal education of any kind—he seemed to innately grasp battlefield tactics and the use of mounted troops to destablilize the enemy’s rear areas. Forrest earned the nickname “the wizard of the saddle” for his lightening raids, and his rear-area strikes became part of the basis for modern warfare strategies and tactics. He was among the most feared commanding officers of the Civil War—Union major general William Tecumseh Sherman once thundered, “that devil Forrest must be hunted down and killed if it costs ten thousand lives and bankrupts the federal treasury.” Much of his success was due to his force of will.

His first combat occurred at Sacramento, Kentucky, in December 1861. In a skirmish with Federal cavalry, Forrest demonstrated the courage—or impetuosity—that would become his hallmark in battle, leading his men in a charge that disrupted his opponents and started a running fight. In Februrary 1862, when the rest of the Confederate command surrendered at the Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, Forrest escaped with most of his horsemen and a few men from other units. At the Battle of Shiloh, there was little opportunity for cavalry action, but he reportedly was among the commanders urging P.G.T. Beauregard to make a final assault in darkness against Ulysses S. Grant‘s position above the river. When the Confederates were driven back the next day, Forrest had the rear guard position and, at Fallen Timbers, he ordered a cavalry charge—only to find himself alone among the enemy soldiers. Though seriously wounded, he managed to escape. In the summer that followed the April 1862 battle he began the raids that would bring him fame.

During U.S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign, Forrest’s men attacked Union supply depots and disrupted Grant’s lines of communication. His career nearly ended at Parker’s Crossroads, Tennessee, on Dec. 31, 1862. While occupied in a skirmish with one group of Federal soldiers, he discovered more bluecoats coming up behind him. He ordered his men to charge in both directions, a bold move that allowed them to escape.

During the course of the war, several horses were shot out from under Forrest. One of them, Roderick, gained fame during the skirmish at Thompson’s Station, Tennessee, on March 5, 1863. After the horse suffered three wounds, Forrest dismounted and ordered him taken to the rear for treatment. According to a legend that grew up around the event, Roderick broke free and leaped three fences to return to Forrest’s side, where a fourth wound killed the gallant horse. The previous month, Forrest suffered one of his few defeats, at Dover, Tennessee, while serving under Major General Joseph Wheeler. Never one to hold his tongue about his superiors, he swore he’d never serve under Wheeler again.

At the Battle of Chickamauga in North Georgia, in September 1863, Forrest’s horsemen were among the first to clash with the Federals of Major General William S. Rosecrans‘ army, but the fight was primarily one of infantry and artillery. When a large portion of Rosecrans’ men routed from the field, Forrest pursued, rounding up hundreds of prisoners. After a falling-out with his commander, General Braxton Bragg, over Bragg’s failure to rapidly pursue the broken enemy, Forrest was given independent command in Mississippi and was promoted to major general on December 4, 1863. The following spring, while raiding in Kentucky and Tennessee, he became a central figure in one of the most controversial episodes of the Civil War, at Fort Pillow, north of Memphis.

Residents of West Tennessee had complained to Forrest about abuse by Union troops stationed at the fort. Those troops included the 13th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment and a few companies of the 6th Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment. Local residents claimed some of the cavalry were Confederate deserters and that many of the United States Colored Troops in the fort were runaway slaves from the area. On April 12, 1864, Forrest invested the 557 men inside the fort with about 1,500 men of his command and demanded its surrender. His demands were refused. After several hours of fighting, the Confederates broke into the fort, and the controversy began. Eyewitness accounts by Union survivors say many of the black soldiers and some whites were killed even after they surrendered, and some were burned alive in their quarters. Even some of the Confederates acknowledged a slaughter took place. Sergeant Achilles V. Clark wrote to his sisters, “The slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor, deluded negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. The white men fared but little better.”

Ever since the battle, controversy has surrounded the question of whether Forrest ordered the “massacre at Fort Pillow,” as it became known, or rode in and stopped it. A Union Army surgeon, Dr. Charles Fitch of Iowa, wrote in an 1879 account that most of the killing took place at the bottom of the bluff, where many of the fort’s defenders had fled in an attempt to reach a Union gunboat in the Mississippi River, and could not have been seen by Forrest atop the bluff. Sergeant Clark, the Confederate who wrote his sisters about the battle, said he and others tried to stop the slaughter but claimed Forrest ordered the Union soldiers to be “shot down like dogs.” On the other hand, another Confederate, Samuel H. Caldwell, wrote to his wife, “if General forrest had not run between our men and (the) Yanks with his pistol and saber drawn not a man would have been spared.” One speculation is that the mercurial, hot-tempered Forrest may originally have given a “show no quarter” order after the fort’s officers refused to surrender but then tried to stop the killing when he saw the battle was won.

About 230 of the 550-plus Union troops were killed. Some 60 black troops and about 170 whites were taken prisoner. Forrest had the most seriously wounded, including 14 black soldiers, sent to the U.S. Navy steamer Silver Cloud. An inquiry by the U.S. Congress two weeks after the battle was inconclusive in its findings. The “massacre at Fort Pillow” had been firmly entrenched in the minds of Northerners, however, through news stories and artwork.

Forrest himself, in his initial report to his superior, Leonidas Polk, wrote that, “The river was dyed, with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed, but few of the officers escaping. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.” His second report corrects and expands upon the casualty totals but omits any potentially inflammatory remarks like those in his first report.

Forrest is quoted in a postwar interview with the Cincinnati Commercial, August 28, 1868, as saying, “When I entered the army I took forty-seven Negroes into the Army with me, and forty-five of them were surrendered with me. I told these boys that this war was about slavery, and if we lose, you will be made free. If we whip the fight and you stay with me you will be made free. Either way, you will be freed. These boys stayed with me, drove my teams, and better confederates did not live.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest After The Civil War

However, the image of Forrest as a butcher wantonly killing black troops at Fort Pillow was reinforced in the public mind by his post-war activities. He joined the Ku Klux Klan and reportedly became its first “Grand Wizard.” Called to testify to Congress, he never admitted membership but only said he had heard about such an organization and its activities. Admitting membership during Reconstruction might have meant prison for him. Supporters attempting to improve his public image often claim he was not a member of the Klan, let alone its Grand Wizard, yet they also credit him with disbanding the group when he decided it had become too violent.

The Ku Klux Klan or Invisible Empire, a 1914 book written by Laura Martin Rose, a native of Tennessee and former president and historian of Mississippi’s United Daughters of the Confederacy, named Forrest the “Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire” and on pages 19–22 gives details on him joining the KKK in Room 10 of the Maxwell House Hotel in Nashville, Tennessee, nearly a year after the group was organized at Pulaski, Tennessee.

Forrest died from diabetes in Memphis on October 29, 1877.

Articles Featuring Nathan Bedford Forrest From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Along line of Confederate cavalrymen interrupted the quiet tranquility of a Kentucky winter as they slowly rode north. Their horses picked their way across the frost-covered ground, crunching through semi-frozen puddles and pockets of deep mud. The first week of winter was hardly an ideal time for soldiering, but these inexperienced troopers were looking forward to their first real action of the Civil War.

Riding at the head of the column’s main body was 40-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest. Tall and well-built, the Tennessee native had inherited the strength and vigor of his father, a blacksmith. Like the eager horsemen in his charge, Forrest itched for a fight. For three months his battalion had been conducting routine reconnaissance operations in Tennessee and Kentucky, and gathering up horses, cattle, hogs, and other supplies for the Confederate army. Such monotonous duty had its purpose, but Forrest expected to make his mark in a more direct and memorable way.

Five months earlier, on July 10, 1861, Tennessee Governor Isham G. Harris had plucked Forrest from the ranks of the Tennessee Mounted Rifles Company and offered him a command of his own. Forrest had enlisted as a private only a month before. Isham, who knew Forrest by his reputation as a businessman in Memphis, commissioned him a lieutenant colonel with the authority to recruit a battalion of mounted rangers.

Forrest wasted no time. Before the end of July, he ran advertisements in the Memphis Avalanche and other newspapers. ‘I desire to enlist five hundred able-bodied men,’ Forrest wrote, ‘mounted and equipped with such arms as they can procure (shot-guns and pistols preferable), suitable to the service. Those who cannot entirely equip themselves will be furnished arms by the State.’ Forrest took this last promise to heart. Prior to the war he had amassed a sizable fortune through planting and slave dealing, and he paid for many of his battalion’s needs out of his own pocket. He quietly scoured neutral Kentucky for revolvers, shotguns, saddles, blankets, and other equipment, and sent his purchases south in wagons. In Louisville, six teenage volunteers helped Forrest smuggle supplies out of the city in coffee sacks.

A vigorous and powerfully built man, Forrest was his own best recruiting tool, inspiring would-be volunteers with confidence in his ability to lead them. Charles W. Button, one of the youths who assisted Forrest in Louisville, recalled his first meeting with the lieutenant colonel: ‘I was attending a military drill with a local company to which I belonged, and as I rode up home, dressed in my new uniform, I saw my father and a splendid-looking man in serious conversation in the front yard. I was introduced to Col. Forrest and told that he was recruiting soldiers, and, as I had already determined to go out, he wished me to go with him.’ After assisting Forrest in Kentucky, Button accompanied him back to Memphis as a recruit.

By November, Forrest’s Tennessee Cavalry Battalion included roughly 790 men from Tennessee, Alabama, Kentucky, and Texas. His recruits found him impressive in both stature and manner. ‘This command,’ Major David C. Kelley wrote, ‘found that it was his single will, impervious to argument, appeal, or threat, which was ever to be the governing impulse in their movements. Everything necessary to supply their wants, to make them comfortable, he was quick to do, save to change his plans, to which everything had to bend. New men naturally grumbled, but when the work was done all were reconciled by the pride felt in the achievement.’

Forrest set up winter headquarters at Hopkinsville, in southwestern Kentucky, on December 20, lodging his troopers in floored tents as they contended with the cold and an outbreak of measles. The lieutenant colonel shared his winter quarters with his wife, Mary Ann, and their 15-year-old son, Willie.

Recruits continued to trickle in. Just before Christmas, a Texan named Adam R. Johnson arrived in camp and offered Forrest his services as a scout. ‘I saw at once that he was a man of great and prompt decision,’ Johnson remembered. ‘His muscular, well-proportioned figure, over six feet in height, was indicative of extraordinary physical strength. But it struck me that his most wonderful feature was his piercing blue eye which flashed and changed so rapidly with every emotion that it was difficult to distinguish its true color. He was a man to catch the look and hold the attention of the most casual observer, and as we gazed on each other I felt that he was a born leader and one that I would be willing to follow.’

As Johnson entered Forrest’s tent, the lieutenant colonel gave him a keen, searching look and asked, ‘Well, sir, what do you want?’

‘I want to join the cavalry,’ replied Johnson.

‘I have plenty of room for you and many more besides,’ Forrest answered. ‘Where are you from?’

‘I am from Texas,’ Johnson said, whereupon Forrest asked, ‘What have you been doing out there?’

‘I have been surveying and fighting the Indians,’ the Texan answered.

‘Well, sir,’ said Forrest, ‘I should like to have you with me. One of my companies is from Texas, and you may go in with it if you wish.’ After making sure he would be allowed to serve as a scout, Johnson accepted Forrest’s offer.

Johnson got his chance to do some scouting sooner than he might have expected. On December 26, Brigadier General Charles Clark, commanding an independent brigade in Confederate Department Number 2, ordered Forrest’s battalion to reconnoiter toward Rochester and Greenville, about 30 miles to the northeast. The unit was to continue north toward Rumsey if it was practicable. ‘We were all lying in camp playing poker and writing love-letters, when suddenly ‘boots and saddles’ rang out on the quiet air,’ Private Charles W. Button remembered. ‘The sick recovered instantly.’ Johnson and fellow scout Robert M. Martin rode ahead of the expedition.

‘Now, Bob,’ Forrest instructed Martin, ‘I want you to start at once for Greenville. Johnson will go with you; and if you learn anything he can come back and report. I’ll not be very far behind you, and you’ll find me on the main road. Go into camp now, get your rations, and start right out.’

After the scouts had departed, Forrest’s command of about 250 men set out on the Greenville Road. The excited troopers did their best to ignore the bitter cold and freezing rain that intermittently swirled in the air. Four miles out of Hopkinsville, Forrest turned east with a portion of his men to scout toward Rochester, and sent the balance of the force on to Greenville, under Kelley’s command. The two columns would link up in a day or two.

Finding the Rochester area empty of Union troops, Forrest started back toward Greenville the next day. On the morning of December 28, a squad of about 40 Tennessee troopers under Lieutenant Colonel James W. Starnes and Captain William S. McLemore met Forrest’s column with news that they had tangled the previous day with Federal cavalry a few miles north at South Carrollton. Forrest pushed on to Greenville to join Kelley while his scouts rode north toward Rumsey to find the Yankee horsemen.

Forrest reached Kelley’s camp outside Greenville shortly after the tired troopers there had fallen asleep after a long night of vigilance. ‘Colonel Forrest came in just as we got covered up,’ trooper Gray remembered. ‘We got up and saddled, mounted our horse, and took up our line of march over the same road we had picketed all night before.’

The Confederate force, about 300 strong with Starnes’ squad attached, quickly assumed the march in one long column. Eight miles up the Rumsey road Johnson reported back to Forrest with news that 500 Federal troops had forded the Green River from Calhoun to Rumsey. Forrest called a halt and ordered all saddle girths to be tightened. ‘Now, boys, keep quiet,’ he said to his men. As word of the Yankees’ presence spread through the ranks, however, Forrest found it ‘impossible to repress jubilant and defiant shouts’ from the charged-up Rebels.

Farther up the road, Button recalled,’several ladies, much excited, waved their handkerchiefs, and told us that the enemy were an hour ahead. Here we struck a trot and moved on as fast as our jaded horses could carry us.’ As Forrest approached the small village of Sacramento, an unabashed Confederate sympathizer named Molly Morehead confronted him, urging the Rebels to hurry. Pointing back toward a nearby hill where she had seen the Federals, she exclaimed, ‘There they are! Right over there!’

Forrest shouted, ‘Johnson, go and see right where they are.’

He remembered Morehead in his official report two days later. ‘A beautiful young lady,’ he wrote,’smiling, with untied tresses floating in the breeze, on horseback, met the column just before our advance guard came up with the rear of the enemy, infusing nerve into my arm and kindling knightly chivalry within my heart.’

Galloping to the crest of a nearby summit, Johnson spied a body of about 200 Federal horsemen a short distance away. He hurried back to tell Forrest, who ‘was trying to persuade the brave girl, who was riding by his side, to retire.’

Johnson assumed that Forrest would halt the strung-out Confederate column and order proper battle formations. ‘But this fiery leader,’ the scout later wrote, ‘without checking his charger, galloped on until he had reached the videttes, whom I had left on the hill-top to watch the enemy, now quite close to them.’ Forrest pressed forward on wet ground rendered treacherous by cold drizzle that had fallen for the last 24 hours. Picking up the pace, the Confederate advance force soon approached the Federal rear-guard. Surprised by the sudden movement, the Union soldiers appeared uncertain as to the Southerners’ identity. Forrest quickly dispelled their doubts. ‘Taking a Maynard rifle,’ he later reported, ‘I fired at them, when they rode off rapidly to their column.’

The Federals retreated over a hill and reformed. When the Confederates were within 200 yards of them, the Yankees opened fire. Forrest ordered the 150 riders who had kept pace with him to close within 80 yards of the enemy before shooting. After a quick flurry of shots, however, he realized that he had too few men to pursue the Federals, and he changed his strategy. Hoping to draw the enemy after him, he ordered his advance troops to fall back.

The plan worked. The Yankee cavalrymen moved forward and were lining up for a charge when the rest of the Confederate horsemen rode up. Forrest immediately dismounted a number of men with Sharps carbines and Maynard rifles to act as sharpshooters.

He ordered Starnes to move against the Federals’ left flank with 30 mounted men, and sent Kelley to flank the enemy’s right with another 60 riders. Meanwhile, the dismounted troopers, concealed behind trees, logs and fences, continued sniping at the Union horsemen. With his saber raised, Forrest thundered to his main column, ‘Charge! Charge!’ and galloped full tilt toward the enemy. ‘Colonel Forrest spoke to the bugler,’ Private Gray remembered, ”Blow the charge, Isham.’ With that, we raised the yell and away we went. The ground had begun to thaw by this time, and we were soon covered with mud from head to foot. Our company was in the rear, and our boys began cursing the two companies ahead of us, whom we thought were riding too slow, and threatened to ride over them.’

The Confederates jumped into the fray with great enthusiasm. ‘…We started in at a gallop,’ Button remembered, ‘and soon passed a couple of prisoners captured by the advance-guard, one of them wounded and both bloody and muddy; a little farther on a loose horse, full rigged, and close by a bluecoat stuck in the mud; then several bluecoats in the same fix…. This was our first chance to ‘mix’ as Colonel Forrest used to say.’

Forrest dashed forward into the enemy’s center, as Starnes slammed into the Yankees’ left. Major Kelley held his squadron in compact order as he drove in the Federals’ right flank. Starnes, having exhausted his revolver’s ammunition, hurled the empty weapon at one of the fleeing Northerners.

The action was fierce, and Forrest was in the thick of it. ‘The Col. was about 50 yards ahead of us fighting for his life,’ Private James H. Hamner wrote. ‘I believe there was at least fifty shots fired at him in five minutes. One shot took effect in his horse’s head, but did not kill him. He killed 9 of the enemy.’

The Rebel horsemen, Johnson remembered, ‘led by this impetuous chieftain, swooped down upon their foes with such terrific yells and sturdy blows as might have them believe a whole army was on them, and turning tail, they fled in the wildest terror, a panic-stricken mass of men and horses, Forrest’s men mixed up with them, cutting and shooting right and left, and Forrest himself in his fury ignoring all command and always in the thickest of the melee.’

Forrest’s apparent ardor for battle astounded his men. ‘Forrest seemed in desperate mood and very much excited,’ Kelley wrote. ‘It was the first time I had seen the Colonel in the face of the enemy, and, when he rode up to me in the thick of the action, I could scarcely believe him to be the man I had known for several months. His face flushed till it bore a striking resemblance to a painted Indian warrior’s, and his eyes, usually mild in their expression, were blazing with the intense glare of a panther’s springing upon its prey. In fact, he looked as little like the Forrest of our mess-table as the storm of December resembles the quiet of June.’

Severely pressed in the center and on both flanks, the Federal party began a disorderly retreat. According to Union Brigadier General Thomas L. Crittenden, the flight began when’some dastard unknown shouted, ‘Retreat to Sacramento!” Most of the Federals chose to obey this mysterious ‘order’ over the entreaties of officers trying to organize a defense. The Confederates chased the Yankees to Sacramento, where, according to Forrest, his troopers ‘commenced a promiscuous saber slaughter of their rear, which was continued at almost full speed for 2 miles beyond the village, leaving their bleeding and wounded strewn along the whole route…. Those of my men whose horses were able to keep up found no difficulty in piercing through every one they came up with.’ Captain McLemore remembered, ‘It was the only time I ever saw a hand-to-hand contest with sabers.’

Standing in the stirrups, Forrest slashed to the left and right among the terror-stricken Federals. Johnson remembered his commander in action: ‘Finally he came up with a man who had been a blacksmith, as large as himself, muscular and powerful. While engaged in combat with this man, another Federal was in the act of running his sword into Forrest’s back, when a timely shot [from a fellow Confederate] felled his second antagonist. Forrest hewed the big man to the ground by a mighty stroke.’

In another instant, Forrest was fighting it out with three Yankees at once. Forrest quieted a private with a pistol shot just as two officers attacked him with their swords, ‘which,’ Johnson recounted, ‘he eluded by bending his supple body forward, their weapons only grazing his shoulder. The impetus of his horse carrying him a few paces forward, he checked and drew him a little to one side and shot one of his antagonists as his horse galloped up, and thrust his saber into the other.’

Forrest’s wounded opponents refused to surrender, so the Confederate commander obligingly renewed the fight. He slashed Union Captain Albert G. Bacon, whom he had already shot, with his saber. He then charged Captain A. N. Davis, and their horses slammed together in a violent collision. Davis was thrown to the ground with a dislocated shoulder, and he surrendered. Moments later Forrest’s frightened mount bolted into the path of two riderless horses, colliding with them and hurling its rider to the ground in a heap. A bruised Forrest scrambled to his feet, but his horse was crippled.

‘Johnson, catch me a horse!’ the lieutenant colonel shouted to his scout. ‘Catching one that came plunging down the road,’ Johnson remembered, ‘I handed him the bridle, but the saddle did not suit him, and while he was getting his own saddle his men gradually withdrew from the pursuit.’

The Confederates had indeed given up the chase. Their horses were exhausted. Forrest’s troopers spent the remainder of the day apprehending Union fugitives and gathering up the wounded and dead. Forrest put Federal losses at about 65 killed and 35 wounded or taken prisoner. General Crittenden estimated the Yankee losses at an unlikely total of 8 killed and perhaps 13 captured. Among the Confederates, there were two dead: Captain C.E. Merriwether had been shot twice in the head while riding beside Forrest, and Private William H. Terry had been pierced through the heart by a Union saber, even as Forrest tried to intervene. Three other privates had been wounded.

One of Forrest’s wounded, recalled Private Hamner, ‘was from our company and was shot by one of our own men. The enemy had on the regular U.S. uniform overcoat, and the man on our side had been in the Mexican War and had on a coat like they had — blue. We were all mixed up together and one of our men took him for a Yankee.’

Forrest dealt kindly with one of the Federals he had unhorsed, a Greenville resident by the name of Williams. The man was severely wounded, so Forrest had him carried carefully to his home, where he was placed on parole and entrusted to his wife. Passing through Greenville on a subsequent expedition, Forrest stopped in to inquire personally after the man. Williams’s wife and children displayed such genuine gratitude for his kindness that the lieutenant colonel was seen to wipe a tear from his eye as he emerged from their home.

The first battle under Forrest’s command left Kelley with a vivid impression of his chief. ‘So fierce did his passion become that he was almost equally dangerous to friend or foe, and, as it seemed to some of us, he was too wildly excitable to be capable of judicious command. Later we became aware that excitement neither paralyzed nor mislead his magnificent military genius.’

The effect of Forrest’s leadership on his troopers was electric. ‘This battle had a splendid effect in our regiment,’ Private J.C. Blanton wrote, ‘causing men and officers to confide in and respect each other. We were convinced that evening that Forrest and Kelley were wise selections for our leaders. And in all the battles that followed in which these two men were actors, they well sustained the reputation made on the field of Sacramento.’

Higher up the chain of command, Brigadier General Clark also took notice of Forrest. In transmitting the lieutenant colonel’s official report of the engagement, Clark added a postcript: ‘For the skill, courage, and energy displayed by Colonel Forrest he is entitled to the highest praise, and I take great pleasure in calling the attention of the general commanding and of the Government to his services. I am assured by officers and men that throughout the entire engagement he was conspicuous for the most daring courage; always in advance of his command. He was at one time engaged in a hand-to-hand conflict with 4 of the enemy, 3 of whom he killed, dismounting and making a prisoner of the fourth.’

Forrest’s unforgettable debut on that cold winter day at Sacramento was a harbinger of ill fortune for his future Union opponents. The blacksmith’s son from Tennessee had only just begun to tap into a fervor for battle that few other men could match. Despite his lack of professional military training, Forrest rode roughshod over his Union foes throughout the Civil War, and rose to the rank of lieutenant general. By then, Northern commanders such as Major General William T. Sherman remembered him simply as ‘that Devil Forrest.’

This article was written by William J. Stier and originally published in the December 1999 issue of Civil War Times Magazine. For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!

More Nathan Bedford Forrest Articles

Articles 3