On the night of March 18, 1882, in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Wyatt and Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday attended a play at Schieffelin Hall. Afterward, Morgan wanted to shoot pool at Campbell & Hatch’s Saloon & Billiard Parlor. For the five Earp brothers—James, Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan and Warren—the air was thick with tension.

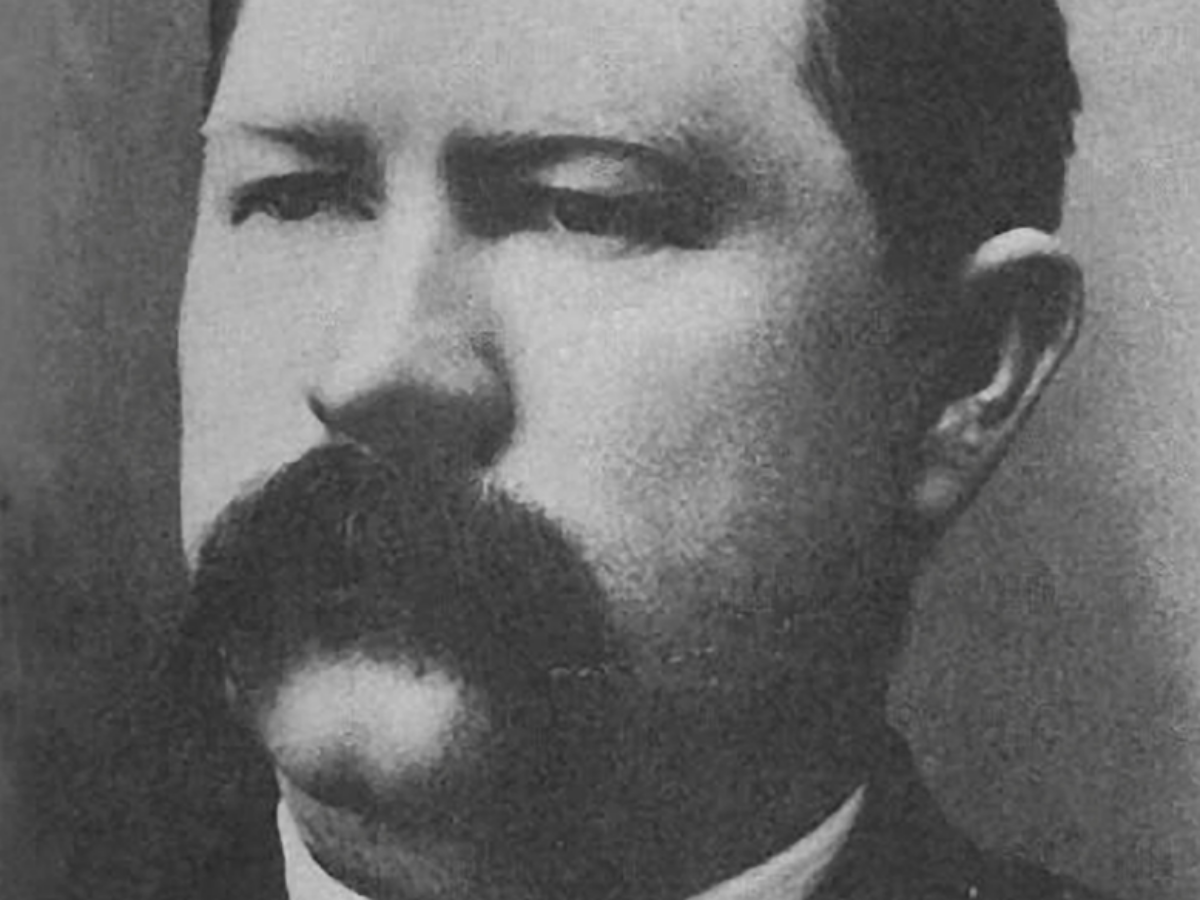

Ever since Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan and Doc Holliday had killed Tom and Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton at the misnamed Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881, Ike Clanton and the other so-called Cowboys had made many accusations and threats. Even though the Earps and Doc had been cleared of murder charges in the shootout, the Cowboys had punctuated their threats with the cowardly shotgun ambush of Virgil on December 28, 1881, permanently crippling his left arm. Wyatt was now a deputy U.S. marshal and working covertly as a Wells Fargo detective, while the incapacitated Virgil, though stripped of his commission as chief of police, was still a deputy U.S. marshal. The Tombstone trouble wasn’t over.

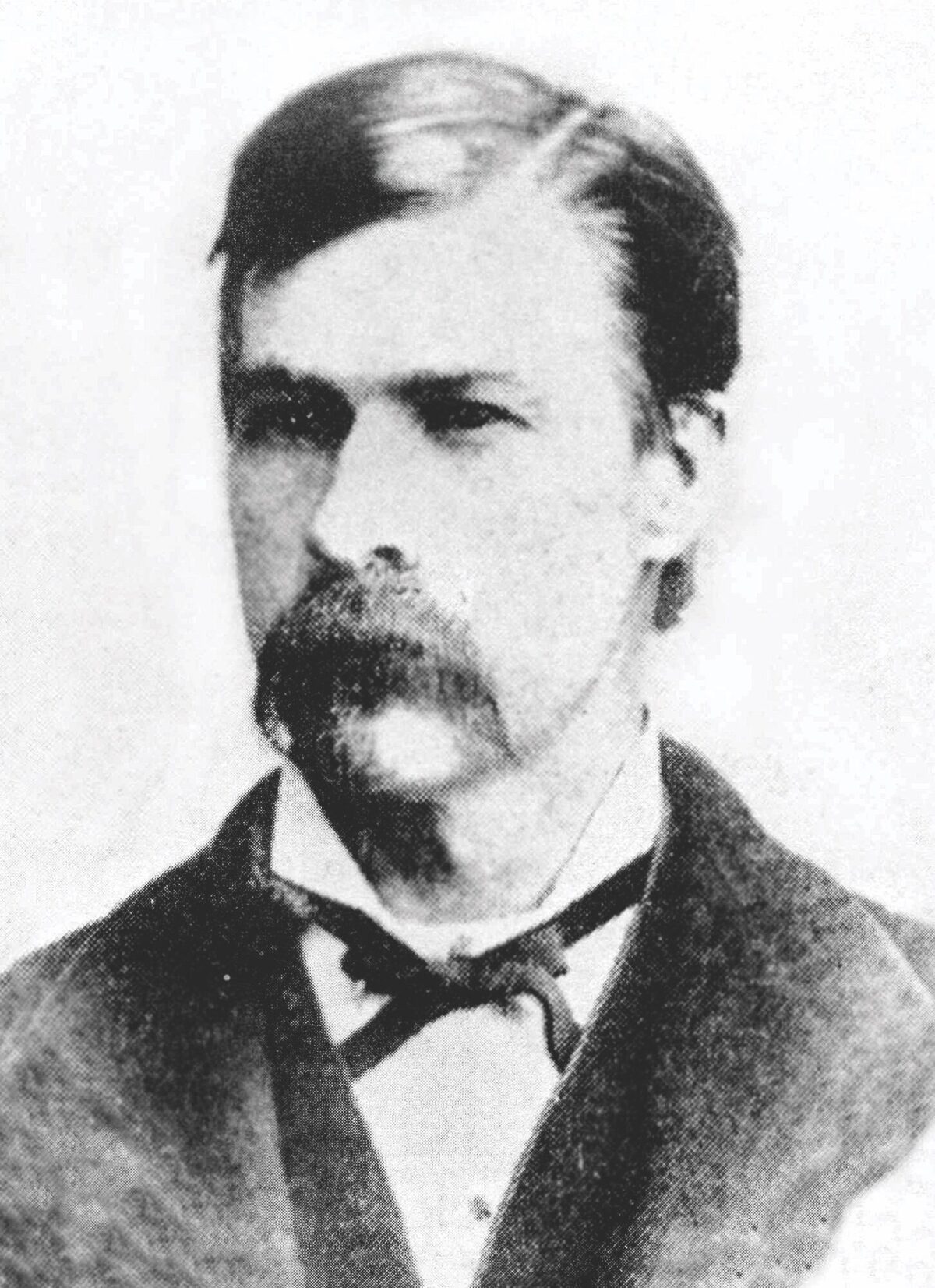

So it was against Wyatt’s better judgment that he was sitting in a chair against the wall at Campbell & Hatch’s, watching Morgan play pool, when shortly before midnight two bullets blasted through an upper window pane of the rear door. The first struck Morgan near the spine, and the second splintered the wall inches from Wyatt’s head. Morgan lay in a pool of blood on the floor and was carried into the adjacent card room. According to Wyatt Earp biographer Stuart Lake, Wyatt and Morgan had occasionally discussed the “visions of heaven” people saw as they died. Now, as he died, Morgan whispered to Wyatt, “I can’t see a damn thing.” Although much of Morgan’s life remains shrouded in mystery, he was reputedly Wyatt’s favorite brother. So it was a sad irony that 30-year-old Morgan died just past midnight on March 19—brother Wyatt’s 34th birthday.

Custer was from the first 13 German immigrant families. They arrived in North America about 1693 from Krefeld and The Rhineland area in Germany. He had older-half siblings, a younger sister and unhealthy brother as well as two healthy younger brothers who served and died with him at Little Bighorn. He had a wide range of nicknames: Autie, Armstrong, Boy General, Iron Butt, Hard Ass, Ringlets.

Recommended for you

Little is known about Morgan Seth Earp, as he was never well known enough to create much newspaper ink. He was born in Pella, Iowa, on April 24, 1851, the next-to-last son of irascible patriarch Nicholas Earp. Ahead of Morgan were half-brother Newton, James, Virgil and Wyatt, with Warren coming after. Fiddle-footed drifter Nick Earp usually made his living as a farmer and part-time politician. So Morgan probably worked on the family farm until age 13, when, in 1864, he went by wagon train with his parents, 16- year-old Wyatt, 9-year-old Warren, and 3-year-old sister Adelia from Pella to Colton, Calif.

A November 24, 1864, entry in a fellow traveler’s diary told how Nick Earp “used very profane language and swore if the children’s parents did not whip or correct their children, he would whip every last one of them.” So Nick’s stern discipline and insistence on loyalty and devotion to family above all else helped mold his sons. Morgan Earp, who would become a spirited, fearless adventurer, was just growing into full 17-yearold manhood in 1868 when Nick again uprooted his family and moved to Lamar, Mo. Most sources would later describe Virgil, Wyatt and Morgan as trim and muscular, fair-haired 6-footers who looked so much alike it was difficult to tell them apart.

Nick lured all his sons to Lamar, where Nick soon became justice of the peace and Wyatt constable. Wyatt married, but his wife, Urilla Sutherland, and unborn son died unexpectedly in late 1870. Shortly afterward, Wyatt, James, Virgil and Morgan got into what witnesses described as a “20-minute street fight” with Urilla’s brothers and other relatives over the alleged bootlegging activities of both families. After the desolate Wyatt skipped town owing taxes he had collected as constable, he and Morgan worked as buffalo hunters in the Texas Panhandle. Sister Adelia recalled, “Wyatt and Morgan went buffalo hunting…in 1871 and came back in 1872 with quite a heap of money.”

Blurbs in the Peoria Daily Transcript in 1872 seem to cast a negative light on Wyatt and Morgan. The February 27 paper mentions how they were fined $20 each and costs for “being found in a house of ill fame” in Peoria, Ill. According to the May 11 paper, the brothers were again fined (each $4.55) and sent to jail because they could not pay. The September 10 paper mentions how Wyatt and other “bawds and pimps” (including Sarah Earp, who called herself Wyatt’s wife) were fined after being arrested in connection with a “floating house of prostitution.” Their names also show up in the 1872 city directory. The brothers may have been between buffalo hunts, just “living” there or been active in the prostitution business, as was brother James all his life. Anti-Earp historians have made much ado about this Earp history, but in those days prostitution was often considered no less moral than, say, the banking business.

In Wichita, Kan., in September 1875, Morgan was arrested and fined $1 and costs for an unspecified minor infraction. In April 1876, brother Wyatt, then a Wichita city policeman, “roughed up” former City Marshal Bill Smith for bad-mouthing current Marshal Mike Meagher’s decision to hire, or attempt to hire, James, Morgan and perhaps Virgil Earp as additional policemen. No official record has been found to prove Morgan ever served as a Wichita policeman.

Wyatt moved in May 1876 to Dodge City, where he was a policeman and later deputy city marshal. His brothers and father occasionally joined him there. Evidence exists that Morgan served legal papers as a Ford County deputy sheriff in 1875, before Wyatt got there. Legend also has Morgan serving as a Dodge City policeman in the summer of 1876. In his biography Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal, and in notes he took while interviewing Wyatt in 1928, Lake states that in the winter of 1876–77, Morgan followed Wyatt to gold-booming Deadwood, Dakota Territory. Although no records have surfaced to confirm Morgan wore a badge in Dodge City, Lake adds that in late 1877 Morgan resigned as a Ford County deputy sheriff and headed for Montana Territory—first Miles City and then Butte. Morgan apparently met Louisa “Lou” Houston in Dodge before moving to Montana. And although she is usually referred to as his wife, there is no evidence they officially tied the knot.

The Benton Record of June 14, 1878, reported the “secret” discovery of gold in the Bear Paw mountains on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in northern Montana Territory, triggering a stampede of prospectors, including Earp. The July 18 Black Hills Daily Pioneer noted that General John Gibbon and his troops had encamped on the Teton River to keep prospectors from being “slaughtered by Indians.” But a blurb in the July 25 Daily Pioneer indicates the danger didn’t scare off Morgan: “Mr. Morgan Earpt [sic] arrived last evening from the Tongue River, which he left about three weeks ago. At Miles City, he found Doc Baggs, Jim Levy and Mike Smith. They did not appear to have any objective point but said they were going in the direction of Bear Paw and would not stop so long as anyone led the way. On the trip, he estimates that his party passed 500 stampeders, most of whom were not well armed and provisioned for the expedition, and some were quite destitute.”

How long Morgan stayed in the Bear Paws, or whether he even got there, is unknown. But here we see a Morgan Earp young and brave enough to chase gold despite the risk he might lose his scalp to Indians. He also showed compassion for fellow “stampeders” who were destitute and/or lacked weapons to defend themselves.

Butte city records show that on December 16, 1879, the town made Morgan a policeman. He served in that capacity until March 10, 1880, perhaps the date of his last paycheck, as evidence suggests he had left Butte a week or so earlier. Sometime during his Montana days, Morgan is alleged to have killed badman Billy Brooks in a gunfight in either Miles City or Butte and was himself wounded in the shoulder. But again, no hard evidence exists that Morgan ever engaged in a gunfight in that territory.

By late 1879, James, Virgil and Wyatt Earp and their wives had settled in the new silver boomtown of Tombstone, Arizona Territory, and Nick Earp was living in Temescal, Calif., near San Bernardino and Colton. Morgan’s wife, Lou, wrote her sister Agnes in a letter dated March 5, 1880: “We arrived in San Bernardino on Wednesday evening, and Thursday we came by train to the Temescal Mountains Warm Springs.…I suppose I will have to live here now for some time, for there is no way to make enough money to get away.” Morgan is listed in the June 1880 census for Temescal. In a July 19, 1880, letter, Lou wrote, “My husband starts for Arizona in the morning.” And in Morgan Earp, Brother in the Shadow, the only book yet written about Morgan, Earp historian Glenn Boyer adds, “Morgan reached Tombstone in late July 1880, just in time to get into the opening bout of the trouble that eventually led to his death.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The lush cattle-grazing land around Tombstone had as many rustlers as honest cattlemen, and the word Cowboy had become synonymous with “rustler.” The booming silver mines and cash being hauled to Tombstone for operating capital also made stagecoach robbing and gambling lucrative pastimes. Virgil held a commission as a deputy U.S. marshal for most of the time the Earps were in Tombstone and twice served as town marshal/chief of police. Wyatt was a Pima County deputy sheriff during the last half of 1880 and a detective for Wells Fargo; he would be a deputy U.S. marshal from December 28, 1881, until he left the area for good in May 1882. After officials carved Cochise County out of Pima County in February 1881, its new sheriff, Johnny Behan, was openly in cahoots with the Cowboys. Thus, the Earps were the only law enforcement in and around Tombstone. But even honest citizens were benefitting from the low price of rustled beef. So the law-enforcing Earps became the bad guys, while the Robin Hood outlaws became the good guys. The resulting confrontations became known as the Earp-Cowboy feud.

In Morgan Earp: Brother in the Shadow, Boyer wrote: “Morgan Earp has never received credit for being a pretty fair, and active, lawman in his own right in Tombstone….The cases in which Morgan was involved are largely routine in connection with working as a deputy for his brothers.” And so, for most of his year and a half as a deputy, Morgan was the mysterious third brother in the background, whose name seldom appeared in the newspapers.

On July 25, 1880, two days before Wyatt took an oath as a Pima County deputy sheriff, rustlers stole a half-dozen U.S. Army mules from Camp Rucker, 50 miles east of Tombstone. Lieutenant J.H. Hurst and a mixed posse of four soldiers and four civilians, including Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp and brothers Wyatt and Morgan, tracked the stolen mules to the McLaury ranch, 15 miles west of Tombstone. Caught red-handed, the thieves made a deal with Hurst: They would turn over the mules to him only if he first ordered the Earps back to Tombstone. The frustrated Earps left, but the weak-spirited Hurst didn’t get his mules back and left emptyhanded. This confrontation was the first of many between the Earps and the Cowboys.

Wyatt rode shotgun for Wells Fargo express shipments until he was appointed Pima County deputy sheriff, on July 27. Morgan took his place as a “messenger,” as the guards were called. Wells Fargo records reveal that in September 1880 Morgan was paid $45.83 for services as a messenger. And in October, November and December 1880 and January 1881, he was paid $125 “general salary,” presumably his regular monthly salary as shotgun messenger. In February he was paid $95.80, recorded as the “last listing” for “Morgan Earp, messenger.” In May his salary payment was only $4.15, and in June it was $16.65, plus another $72 for a “search of robbers.” In October he was paid $12 for “pursuit of robbers,” and in November the “Earp Bros.” were paid $6.50 for unspecified services.

The August 17, 1880, Tombstone Epitaph reported that Pima County Deputy Sheriff Wyatt Earp had deputized Virgil and Morgan to chase down four horse thieves headed toward Mexico but that at Charleston the two cornered a Mexican mule thief “who put up a fight until Morgan ran a six-shooter under his nose.” On August 25, Wyatt and Morgan rode to nearby Watervale to arrest teamster George McKinney for shooting down Captain Henry Malcolm during an altercation with a third man, Charles Mason. Morgan took McKinney to the Pima County jail in Tucson. His delivery of prisoners to Tucson for Pima County Deputy Sheriff Wyatt Earp and Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp would become an oft-repeated task.

The September 11 Epitaph reported that Morgan had been riding shotgun on a stage to Benson when he discovered the rear boot had torn open and two bars of silver had fallen out. Backtracking, Morgan and the driver found the bars lying in the road. The incident may have planted a seed for later accusations by the antiEarp faction that the brothers were behind many area stage robberies.

A much more serious incident occurred on October 28 when Tombstone Marshal Fred White tried to arrest Curly Bill Brocius, who with some other drunken Cowboys had been “shooting at the moon.” Hearing the gunfire, Deputy Sheriff Wyatt Earp came up behind Brocius and grabbed him just as he was handing over his six-shooter to White. The gun went off, and White fell mortally wounded. Wyatt buffaloed Curly Bill over the head and stuck him in jail. Morgan and Wells Faro undercover man Fred Dodge then stood guard as Wyatt rounded up the other drunks. When Wyatt took Brocius to Tucson for trial, Virgil and Morgan rode shotgun part of the way, as they feared a lynch mob might try to hang him. A judge later acquitted Brocius of murder because White had called the shooting “an accident” before he died.

And so we begin to get a picture of Morgan Earp in Tombstone—pinning on a badge whenever asked, but also gambling at the tables whenever he could. When Wyatt’s old pal John H. “Doc” Holliday showed up in Tombstone in mid-September, legend has it Doc and Morgan also became bosom buddies. Legend also says both were hottempered, though Boyer wrote that “Morg had a pretty amiable nature.”

After Wyatt resigned as Pima County deputy sheriff on November 9, 1880, Morgan no longer chased bad guys for him, but Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp continued to call on Morgan in 1881. Two more of Wyatt’s Dodge City pals also showed up—Luke Short in January and Bat Masterson in February. Wyatt had a piece of the action at the Oriental Saloon, and Bat and Short settled into gambling there along with Doc Holliday and the four other Earp brothers—James, Virgil, Morgan and Warren. Ironically, they often played cards with some of the Cowboys.

Meanwhile, rustling and stage holdups were increasing in frequency and violence. The cauldron began to boil over on the night of March 15, 1881, when four holdup men killed driver Budd Philpot and passenger Peter Roerig during a bungled attempt to rob the Tombstone-to-Benson stage. Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp, Wells Fargo detective Wyatt Earp, Morgan Earp, Masterson, Philpot’s shotgun messenger Bob Paul and others formed a posse. They soon caught up with one Luther King, whom either Wyatt or Morgan “persuaded” to identify the other three robbers. But the posse’s grueling 400-mile chase came up emptyhanded, falling apart after Virgil’s horse dropped dead from exhaustion. Worse still, the Cowboys accused Doc Holliday of being behind the robbery attempt. Wells Fargo secretly gave Wyatt carte blanche to put an end to the stage robberies, and on June 28 Virgil was appointed chief of police of Tombstone on top of his deputy U.S. marshal’s badge. A showdown with the Cowboys was inevitable, and Morgan Earp stayed eagerly in the midst of the action.

On August 13, Mexican Rurales killed “Old Man” Clanton (father of Ike, Billy and Phin) and six other Cowboys over a herd of rustled cattle in Guadalupe Canyon, just across the border in New Mexico Territory. Some historians believe Wyatt, Morgan and Warren Earp and Doc Holliday were involved in the killings, which would have inflamed tensions. In September a posse that included Virgil, Wyatt and Morgan arrested badman Pete Spence and Frank Stilwell, who was one of Sheriff Behan’s deputies, for robbing the stage to Bisbee on the 8th, causing further friction between the Earps and Cowboys. Cowboy Frank McLaury later stopped Morgan outside the Alhambra Saloon and warned, “If you ever come after me, you will never take me.” Morgan replied if he ever had occasion to go after McLaury, he would arrest him. As Morgan calmly walked away, McLaury said, “I have threatened you boys’ lives, [and] since this arrest, it now goes.” After that, the Cowboys began boasting of wanting to kill the Earps

Nevertheless, in October 1881 when Geronimo and his renegade Apache warriors went on the warpath, threatening the Tombstone outskirts, a 17-man Earp posse that included Morgan had an oddly peaceful exchange with Curly Bill Brocius at the McLaury ranch in the Sulphur Springs Valley on the 6th. Diarist George Parsons wrote, “The best of feeling did not exist between Wyatt Earp and Curly Bill, and their recognition of each other was very hasty and at some distance,” though Virgil “had a chat” with Curly Bill before the outlaw leader rode off. Apparently, at that point, everyone was more concerned about the Apaches.

On October 21, Wyatt, who had been appointed a temporary policeman by brother Virgil, sent “special officer” Morgan to fetch Holliday in Tucson. Wyatt had previously made a secret deal with Clanton to set up some of his stage-robbing friends for arrest, and Clanton thought Wyatt had betrayed that confidence to Doc. Pro-Earp historians believe Wyatt sent for Doc so he could confirm to Ike that Wyatt hadn’t told him anything. But anti-Earp historians believe Wyatt sent for Doc to set up a climactic showdown with the Cowboys—resulting five days later in the gunfight.

On the night of October 25, a drunken Ike Clanton got into a mouthing match with Holliday at the Alhambra. Morgan and Wyatt separated the pair, and then Virgil arrived, threatening to arrest both Doc and Ike. Ike stalked off, muttering he would be “after you all in the morning.” He ended up at the Occidental Saloon, engaging in a poker game with Tom McLaury and Johnny Behan but also, curiously, Virgil and possibly Morgan.

The next morning, the 26th, Ike was back spouting threats and drunkenly walking the streets with a six-gun and a Winchester rifle. When Virgil confronted him, Ike tried to pull his sixshooter. But Virgil buffaloed him and, with Morgan’s help, hauled the ornery Clanton off to court. In court Wyatt and Morgan got into another verbal barrage with Ike, Morgan mockingly offering Ike his own six-gun and daring him to use it. Judge A.O. Wallace slapped Clanton with a $25 fine for carrying a gun within city limits and confiscated his weapons. And as the still-fuming Wyatt left the courtroom, he ran into Tom McLaury, buffaloed him and left him dazed and bleeding in the street. Ike Clanton had finally blown the lid off the stewpot.

At about 2:30 p.m., Virgil Earp led “special policemen” Wyatt, Morgan and Doc Holliday to a 15-foot-wide vacant lot on Fremont Street behind the O.K. Corral. They went there to disarm any Cowboys illegally carrying guns. Perhaps neither side expected the confrontation to erupt into a gunfight, but it did, with about 30 shots fired in 30 seconds. Billy Claiborne and Ike Clanton ran. Who shot first remains a never-ending controversy. Tom and Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton were killed. A bullet passed through Virgil’s right calf, another bullet grazed Doc’s right hip, and Morgan took a bullet crossways from the right shoulder through his left shoulder. In a January 31, 1882, letter to her sister, Lou wrote that husband Morgan “was shot through the shoulder, both blades were broken and the spinal column slightly injured.” It is believed Morgan rose partially to his feet after being hit and fired the last shot of the gunfight—hitting Frank McLaury in the right side of the head, killing him instantly.

Morgan recovered from his wounds and continued to serve as a field deputy for Virgil despite further Cowboy threats. The day after the crippling ambush of Virgil on December 28, U.S. Marshal Crawley Dake commissioned Wyatt as a deputy U.S. marshal, and Morgan continued to ride as a field-commissioned deputy for Wyatt. Morgan was still doing that when the Cowboys assassinated him on Saturday, March 18, 1882.

On Sunday, the 19th, James Earp took Morgan’s body to Colton, Calif, for burial. The next morning’s Epitaph reported, “The funeral cortege started away from the Cosmopolitan Hotel about 12:30 yesterday, with the fire bell tolling its solemn peals of ‘Earth to earth, dust to dust.’” (See related story in the October 2006 Wild West.) Morgan’s widow, Lou, expressed her desire for justice in a March 22 letter to a friend: “God is too just to let his murderers go unpunished.”

A wounded Virgil and wife Allie left town on Monday, March 20, also bound for Colton, leaving just Wyatt and Warren in Tombstone. Filled with guilt and rage, with Warren and Doc in his posse, Wyatt began his infamous vendetta ride against the Cowboys.

Even in death, Morgan the mysterious does not rest wholly in peace. In 1892 railroad crews built a new right-of-way through Colton’s Slover Mountain Cemetery, where Morgan’s body was buried. On November 29 of that year, workers exhumed and reburied Morgan’s remains and the other bodies at nearby Hermosa Gardens Cemetery. Legend suggests their identities were scrambled during the move, but the current cemetery staff insists it knows exactly which grave is Morgan’s. The late Earp historian Truman Fisher put a corrected new marker atop the grave, replacing one that labeled Morgan a “U.S. Marshall” (spelled wrong). Of course, Morgan was never a U.S. marshal anyway, but a deputy U.S. marshal. And in a final ignoble turn, Hollywood has repeatedly portrayed Morgan as the weak brother, when he was just the opposite.

Clearly, Morgan had stayed true to the law, or at least to his brothers till the end. Since he left no diaries, exactly what motivated him in his short life will forever remain a mystery. Nevertheless, his name has become legendary today. It is safe to say Morgan probably would have died unknown if he hadn’t been the brother of Wyatt Earp and been involved in the most famous gunfight of the Old West.